What food would you say is your specialty?

The interesting thing about today’s question is I suppose what is meant by specialty. The word has a kind of professional air to it, so that a working chef would talk of a specialism that they could say they were expert in. It might be a food nominated on the basis of a national or regional culture or a genre of food based on what is being offered to eat – fish, beef or specifically vegan fare.

On the other hand it may merely refer to the food a person especially likes to eat, although, specialty implies perhaps even here a kind of refinement of taste that makes fine distinctions based on specialised techniques or styles of cookery or presentation. This isn’t necessarily about the class based refinements of ‘fine dining’ because it might, and often is, referred to kinds of street food within specific cultures.

Basic or fine dining?

It is possible I suppose to be a specialist in fish and chips in the UK but I think the term would have layers of irony even when applied within the UK. They would be distinctions based on class or of quality that exclude anything but the haute cuisine ‘reconstructed’ version of basic British fare.

But all this aside, the point I want to make is that a specialist food can only exist where choices are being exerted based on any number of associations, from those of class (does Beluga caviar still get served as a sign of the wealth and status of someone in UK restaurants or would that idea now seem vulgar and like the aping of an old idea of social class and status) for instance, to issues of presentation and refinement of taste combinations.

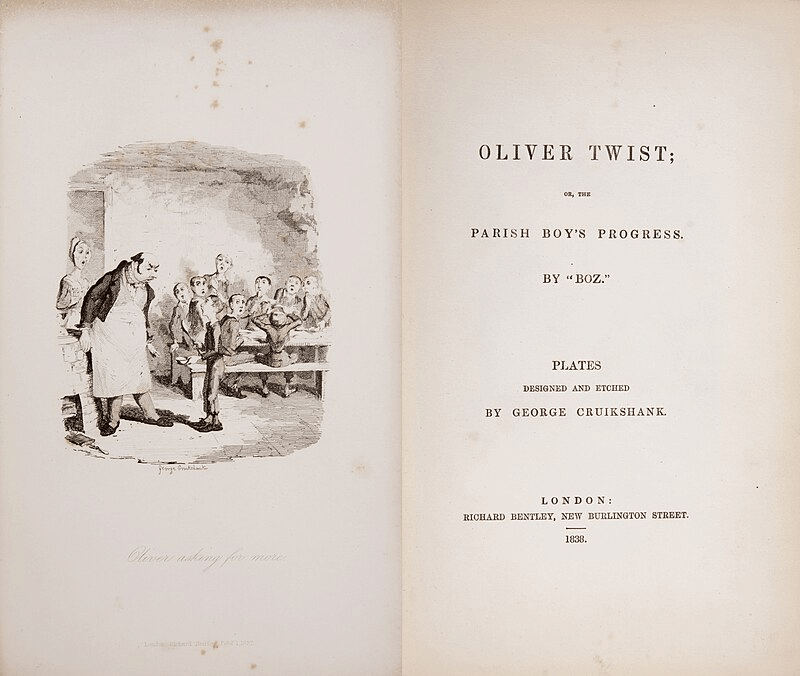

For some people, food cannot have those associations because choice from its range of potentials is absent. The symbol of destitution in literature in the nineteenth century has always been the base nature of an eked out food resource that despite the poverty of its substance (most commonly represented by ‘gruel’ in the nineteenth century) is still in short supply. Hence, perhaps the iconic status of Oliver Twist’s plea to ‘want some more’ in the novel bearing his name. That combination of scarcity and baseness in a food you might never choose is of course also prominent in Jane Eyre.

The phantom of Want is the first of the ‘five great evils’ of an unjust, and as the author of the Beveridge Report in 1942 in the UK thought too, uncompetitive society. Stephen Armstrong writes, 75 years after the Report in 2017 in The Guardian, that that Report made ‘a wide range of suggestions aimed at eradicating what he called the five “giant evils”: want, disease, ignorance, squalor and idleness’.

Want did not just mean food poverty but it was most usually thought of in those terms, as witnessed by the vast growth in foodbanks in the UK but in Canada too, where some see them not as ameliorating but further exacerbating food poverty, even in Canada. Foodbanks in the UK were reserved for extreme cases of deprivation when I first started in social work but are now needed by many, even in the population at work in the gig or other low-pay economy stimulated by modern neoliberalism. They are not accessed as then through health and social care professionals such as I was once.

Foodbanks an issue, even in Canada (see link for source of photograph).

Next to food poverty the image of food prominent in art has been in relation to excess – in the social image of the cornucopia in agricultural economies, including Ancient ones. EXCESS is a sign as great as starvation and WANT of an unjust system. Dickens often stated this (to excess perhaps) by the picturing of the excesses of the wealthy, even the moral wealthy, in Oliver Twist for example. Hence the need to represent Want in the nineteenth century by thin gruel – which even Scrooge, his miser in A Christmas Carol prefers to eat to avoid visible excess, and accumulate excess in a more symbolic and secreted and even more self-obsessed, form

In all these cases FOOD is not about choice and the quality of that food, in its source, combination, cooking and presentation but about the GROSS quantity of it relatively. And this marks how much food is a sign of qualitative differences that are only partly explained by association. The meme above is meant to compare rich excess with poverty. Of course we need to take into account the fact that comparisons between nations need the nuance of comparisons internal to each nation (to avoid not only inaccuracy but stereotypes). Though such a meme stresses an extreme, it also shows that deprivation is relative, although we think of WANT as absolute. About the meme above, for instance, some people point out that the poor South-East Asian orphans there eat a better and more nutritious food than the rich teenagers ‘above’ them stuffing in a fast food chain variety foodstuff. But those teenagers do have choice, or at least apparently so, and their specialty food – even if it be a MacDonald’s burger – represents an area of choice not available to those whose food supply is controlled from persons with more power. A person who especially likes Burger King in comparison with MacDonald’s Burgers may even see that as a specialty in their taste, though others might see the height of vulgarity and lack of taste (and perhaps lack of health-consciousness) in choosing to eat either.

When eating is represented in art issues of the moral quality of the eater are often implied as if their choices represented an external sign of other qualities than their income or accrued wealth. This is certainly partly the issue though in Giambattista Tiepolo’s The Banquet of Cleopatra (1744), featuring ‘a supposed historical banquet, hosted by Cleopatra for Marc Antony, and described by both Pliny‘s Natural History (9.58.119–121) and Plutarch‘s Lives (Antony 25.36.1). During this banquet Cleopatra takes an expensive pearl and dissolves it in her wine, prior to imbibing the drink’.

Available at (as with quotation describing its subject above) at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Banquet_of_Cleopatra_(Tiepolo)

Everything in this painting equates the food assumed in it, and of course drink, with excess, and conspicuous consumption thereof, on a grand scale, which is analogous to the sexual appetites of the main protagonists and feasters. Dissolving a pearl in one’s wine, as Cleopatra does, is only matched by a feast aimed at the eyes as well as the refined tastes and the elite gut. There is much more to the painting than than this, but that is my only point in this respect. Look at how the clothes, gestures, setting and social attitudes bespeak excess and waste – even the play between minor characters surrounding this Imperial Greek-African princess.

I have already mentioned another key example as interesting as the luxurious food and sex wanton represented by this mythicised Cleopatra. The other motif is of a person as thin as she is fleshly and fulsome. It is the key example in nineteenth century fiction of the miser. What Scrooge in A Christmas Carol will allow himself to spend on food for others and himself is a mark of his moral transformation. His isolated eating of poor food is a sign of someone who fails to acknowledge any form of tangible or intangible humanity.

In modern novels such broad brush strokes of moral characterization don’t happen outside of popular genres but they happen with great nuance in a novel I recently blogged upon: Bellies by Nicola Dinan. (See the blog at this link).

However, the greatest novel to use food as a central dynamic motif (to my mind at the moment as I scan it for I am sure to have forgotten something – I always do) is La Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris) by Emile Zola. Even a VERY low key summary of the novel from the Preface to the 1955 English translation (under the coy title Savage Paris) by David Hughes and Marie-Jaqueline Mason says useful things that point out the centrality of the different functions of food in the novel. Hugh Shelley says that ‘the subsidiary characters, often condemned as superfluous’ help us to understand that the world of the food market at Les Halles is the world of interlocking systems in which food is discoursed upon:

Lisa may see the meat and fish and vegetables in terms of profit and loss, and Florent aas the cause and effect of gluttony: they are the matter of art for for the painter, Claude, and the bed and board of Marolin and Cadine, the orphans who grow up to thieve and feast and couple inside the monster.

Hugh Shelley (1955:6) in ‘Preface’ to Emile Zola (trans. David Hughes and Marie-Jaqueline Mason) ‘Savage Paris’ London, Elek Books, 5-6.

Much more sophisticated analysis of the novel is possible but I want merely to say that food is the beginning and end of this great novel, as it attempts to encapsulate the whole set of economic, social and cultural systems relating to food, from poor peasant farmers bringing produce in from Paris’ agricultural hinterland, to the slaughterers of animals in the underground systems of Les Halles, and the visceral smell and taste, even just as we smell alone, of cheese, in its most noted passage.

The action takes place in a literal ‘belly’ of food processing,exchange and consumption, Les Halles in Paris, now the site of the Pompidou Centre. We see retail shops of quality and none, explore the vaults where slaughtered animals have seen the last of the world before being masticated into fragments with a commodity value of their own. And throughout food is a symbol of the persons who help produce, process, retail and consume it. Class society can be seen in process in these events as can the vast inequalities shown in access to consumables by type as well as quality.

And the novel has a thought too to the wastes involved in the above process. It is a novel with a kind of brutally excremental vision and shit is literally everywhere – in the morality of interaction between people, politics and art too as well as the social economy. But Hugh Shelley is right to pick out Claude Lantier, who will become the focus of Zola’s later exploration of art with touches in him of his friend, Paul Cézanne.

Claude sees Les Halles as a a palace and a cathedral dedicated to consumption and as worthy of art as they as of the enthusiasm of a social observer or Piranesi: ‘a vast oriental structure of metal as frail as the hanging gardens, criss-crossed by falling terraces of roofs, aerial corridors, flying bridges thrown out into space’ (‘Savage Paris‘ page 185).

Even the people there are ‘a glorious subject for a picture’ (and perhaps a Cézanne picture at that): ‘these vendors under their large faded umbrellas, red and blue and mauve, attached to sticks, little humps of colour here and there, through the market, catching the fire of the setting sun with their vigorous rounded shapes, a sun that was slowly fading from the carrots and turnips’ (‘Savage Paris‘ page 186). A mean cut at the boyhood friend painter here I think even before the novel over which they stopped speaking to each other was published. Brilliant beautiful, this novel digests it’s society like a belly in itself that collects, consumes, develops a beautiful interior and exterior in itself – and excretes out the waste

So if I have a specialty in food it is the food in art. Let’s discuss it.

With love

Steve

3 thoughts on “The art of eating.”