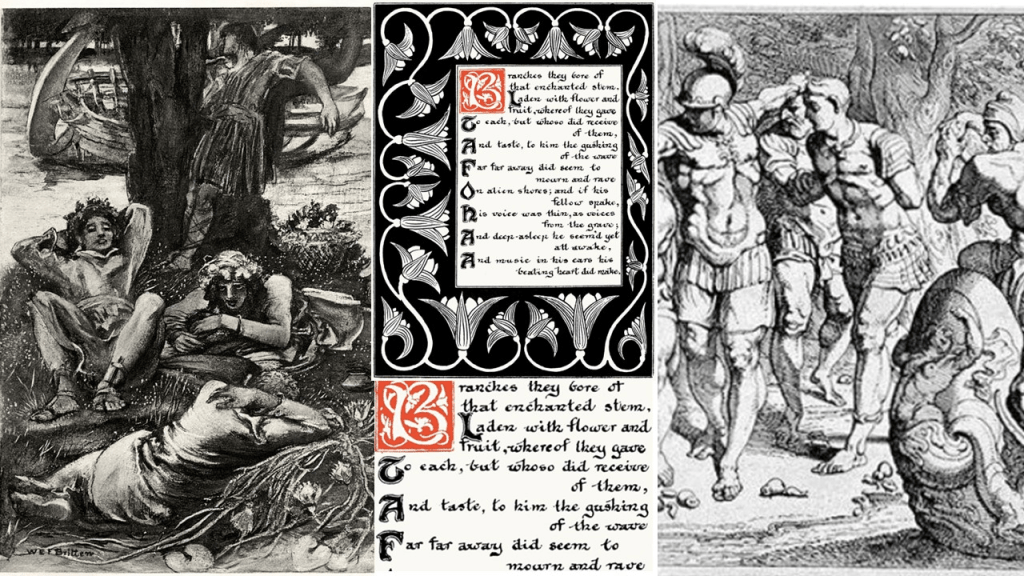

When Tennyson imagined ‘lazy days’ he turned to a myth of a kind of rest that felt like giving up on what till now has seemed your allotted mission in life. He chose, as often, to retell a story about Ulysses from Homer’s The Odyssey to imagine both a man with a mission – for him and the sailors who crewed his ship to reach their homes again – and the call to rest, represented as one of the many threats to the life of the man and his followers. In a sense the threat of the Lotus-Eaters, promising a life lived in a drugged stupor where the senses, especially of sound and smell, and the feelings have the impact that a sumptuous dream might have on an aesthete. All sound feels like music that soothes, not stimulating but inhibiting the body and mind. All scent is that of a powerful soporific – so strong that as you taste it, your mouth relaxes into that looseness that sleep allows but that consciousness of being seen would never permit. In contemporary illustrations to the poems also, laziness is equated with a giving up of, rather than resting from, duty, with Ulysses’ mariners looking frankly drunk, their ship sinking in loose sand.

Partly he wrote that amazing poem to sum up an aesthetic tradition he loved and yet distrusted – especially that tradition flowing through the poetry of John Keats – which swoons into a longing that barely distinguishes between dream-filled sleep and death. That lack of distinct separation of rest from death lends to the recreation of the relaxed body and mind in the poem the qualities of its melancholy, as it does in Keats’s Odes at times – especially in To the Nightingale. But The Lotos-Eaters is a poem quite unlike anything Keats might ever have written. That is because Tennyson knew that the society he lived in was no dream – whatever the delights of his entitled life as a revered and well-fed gentleman in Farringford House on the Isle of Wight or as a guest of the powerful in the land, who were forced to admire him because of his riches and social reputation as the Poet Laureate and guest of Queen Victoria.

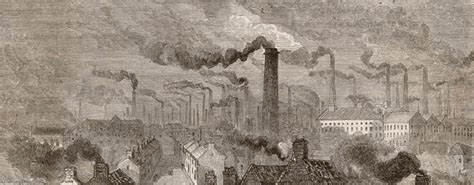

There is no doubt that he understood the fact that British wealth was now founded as much on the bourgeoisie having persuaded the working populace of myths of the necessity for labour (urging it to sacrifice itself to industrial production) as on the land interests associated with the rule of ancient aristocracies. Indeed, the latter now often allied themselves to the former upcoming moneybags chiefs of the economy. He also understood that ‘labour’ may be more metaphoric in a capitalist society for those living in the main from unearned income. That class is surely the ‘others who in Elysian valleys dwell’.

A page of the website of the Victorian Gothic Farringford House and Estate on the Isle of Wight, once the luxurious home of Alfred and Emily Tennyson and now a luxury hotel is associated with rest and relaxation – at a price. This a page from the hotel website: https://farringford.co.uk/history/estate/house-and-estate-history.

It amazes me how luxuriousness so characterises this poet. It still characterizes him in that Farringford hotel where anyone who holidays there must look relaxed having paid an enormous price to do so and implicitly boast the wealth that made this possible. This privileged feel sometimes looks odd to lovers of a poet as troubled as Tennyson often was who associate that with a poet’s social conscience. His later poems disguised his suicidal fantasies, that are on the surface in poems written in the early 1830s and very clearly evident in The Two Voices (published in 1842):

Then comes the check, the change, the fall,

Pain rises up, old pleasures pall,

There is one remedy for all. (ll. 163-165).

And though In Memoriam in 1850 disguises Tennyson’s longing for release from life in the notion of mourning and deeply repressed desire for his deeply beloved friend, Arthur Henry Hallam, it is there quite independent of its ‘triggers’ (as people call stressors these days). It is there too in jingoistic British myths of vulgar nationalism with which Tennyson indulged his age: at the worst in The Charge of the Light Brigade, but present too in his attempt to symbolise the fate of the British nation by resuscitating Malory’s Morte D’Arthur myths in The Idylls of The King. Luxury and melancholy go together in The Lotos Eaters for they are both a temptation from association with home-truths (quite literally so) for Ulysses – a temptation that takes him from a mission that might comprehend the less fortunate in society.

The Gods that Tennyson, in his guise as Ulysses, imagines are not only selfish about their entitlement, they also see the laments of its absence in those who actually produce the wealth on which the entitled sit as a kind of natural art for their delectation in Elysium (or the halls of the rich whether in Manchester or a country-house):

…, they find a music centred in a doleful song

Steaming up, a lamentation and an ancient tale of wrong,

Like a tale of little meaning tho’ the words are strong;

Chanted from an ill-used race of men that cleave the soil,

Sow the seed, and reap the harvest with enduring toil,

Storing yearly little dues of wheat, and wine and oil;

Till they perish and they suffer—some, ’tis whisper’d—down in hell

Suffer endless anguish, …

The critique of entitlement to seemingly eternal rest – the endless holiday of unearned wealth – is very precise. This privileged mode of living does not ignore anything in the world, even suffering: it aestheticises it so we feel the strength of the words of folk songs of suffering. Many such songs were being produced by working-class poets in the NORTH OF England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland especially. The aesthetic divinities though find ‘little meaning’ in them – nothing that might spur a God or a poet to social action rather than inaction politically and away from their leisure. Tennyson never made the leap to anything other than the sad politics of his privileged class position but I love that he saw the contradiction and made it open to public examination.

I think this poem expresses where I am on this question. I find ‘rest’ a mythical proposition. Like Tennyson, except I lack his talent entirely, I find the state of excitation in my nervous system always too great to rest or ‘relax’.The man who laid back on a bed with ear-plugs that transmit music that gives to him a beauty independent of the issues of the minutes pressing to be born would feel to me an entirely alien person with whom to identify though I might love him. When I have seen people able to do it, the personae of the Lotos-Eaters absorb into their identity in my mind that laid-back man for they seem (if not put by me into these words) persons who succeed in making time seem as if it had no force or energy to which they feel compelled to answer. They live in ‘A land where all things always seem’d the same!’. And then as they arise from their bed of rest to approach my imagined boat: a boat keen, on its own volition, to sail on, even if (were it possible, with the embedded rester).

And round about the keel with faces pale,

Dark faces pale against that rosy flame,

The mild-eyed melancholy Lotos-eaters came.

I love the play of ‘dark’ and ‘pale’ in these lines: the kind of pallor is a place where non-calorific substances have overtaken the attraction of shared foodstuffs and life seems like smoke, or a fulfillment that you can smoke. It’s also full of the shadows of meaning, the ‘dark conceit’ of imagery of which poets from Edmund Spenser speak. Meanwhile, I suppose I feel rather plagued by time myself: the coming minutes (absent for the man on the bed or a Lotus-Eater) crowd on me and name themselves the next mental task to be accomplished. I have to say ‘mental task’ for that predominates now in me even when it requires physical tasking too (that is the fate of someone once having discovered the social worker in them) and it demands attention – immediate attention. That mind process – with its apparently (but only apparently) self-energised dynamic – leaves little left (time or motivation) for holiday or relaxation unless it is with art that stimulates and in which I yearn to find meaning, whatever the strength of ‘words’ or painterly marks in them.

So I don’t feel rested but I wonder if that is because I feel unproductive when resting. I think not. Moreover the desire to endlessly PRODUCE is a symptom of a world obsessed with economic growth, and not with the enhancement of the thought, feeling and sensations that, through introjected energy, make life mean something. The practical person might turn to me and say, ‘but who pays for you finding meaning in life, which for some is a kind of luxury, and comparatively a rest from hard labour’.

Provided that is not said aggressively and dismissively, I hope I will turn round to them and say: ‘Yes, that is the contradiction’. Because that’s another reason I can’t rest or relax. For it is not enough for the few ‘in Elysian valleys dwell’. We most seek that upland plain for the many. It will not be a restful place, and it will involve more physical tasking than I have done since retirement, but it will not either be a rest in drugged dreams, where the pace is that of ‘downward smoke’ and the only thing that climbs is sleepy desire – Tennyson’s ‘shadowy pine’:

A land of streams! some, like a downward smoke,

Slow-dropping veils of thinnest lawn, did go;

And some thro’ wavering lights and shadows broke,

Rolling a slumbrous sheet of foam below.

They saw the gleaming river seaward flow

From the inner land: far off, three mountain-tops,

Three silent pinnacles of aged snow,

Stood sunset-flush’d: and, dew’d with showery drops,

Up-clomb the shadowy pine above the woven copse.

All my love

Steve