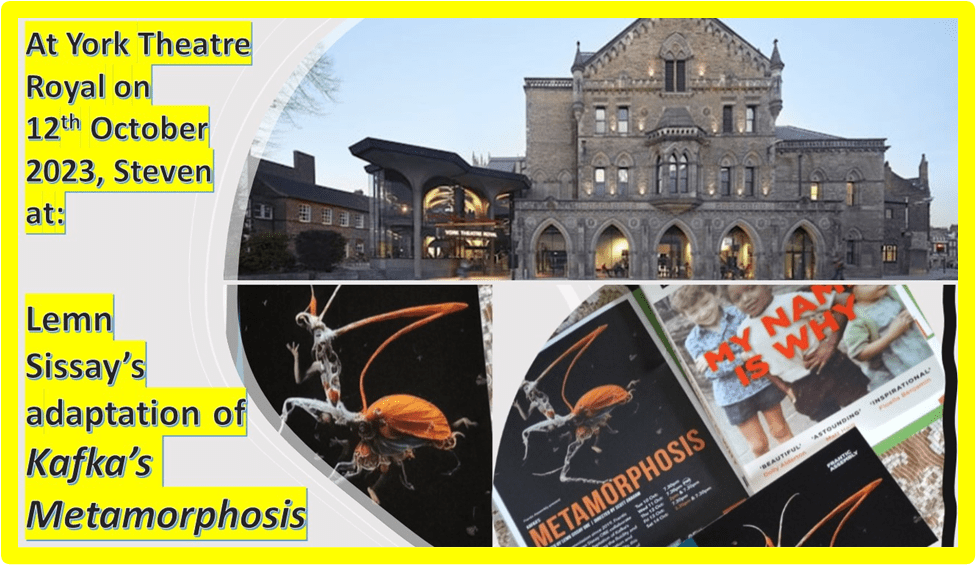

This blog is a sequel to seeing Lemn Sissay’s Kafka’s Metamorphosis, an adaptation, retelling (and more) in a new dramatisation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis with the company Frantic Assembly. I saw it at York Theatre Royal on Thursday October 12th at 2.00 p.m.

In my earlier blog on this play, I previewed my expectations of the performance on which I’m reporting today. I said there that I particularly wanted to prepare for seeing it for a number of reasons stated in that blog, which can be accessed at this link. I say there too all I wanted to say at the time about the playscript as I read it (as written pre-performance and thus before changes that might have been made). But reading the playscript at any point can barely help to imagine a theatrical version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis of the order of innovative theatre and stage, acting and movement craft as provided by Frantic Assembly, the company who performed it.

This was not a company I had seen before nor, I must admit, even heard about. This must be to my shame for a large chunk of the audience who saw it with me were from a local grammar school and were studying (I was sitting next to one of their teachers as accident would have it to ask these very questions) not the play or the novella – although there were apparently 4 A-Level-German students here studying the novella in its original language – but the company Frantic Assembly for the drama GCSE classes. After seeing this performance I can see why. Apart from inappropriate wolf whistles at the playing out of the incest theme, that audience found it, it seemed, as breathtaking as I did. Moreover so breathtaking did I find the performance, on the way home via the second heavily delayed LNER train of the day, I rang my husband to request that he book for us to see the production again when its tour reaches Northern Stage Theatre at Newcastle. He did so (for I claimed he really had to see it) and we go on October 26th.

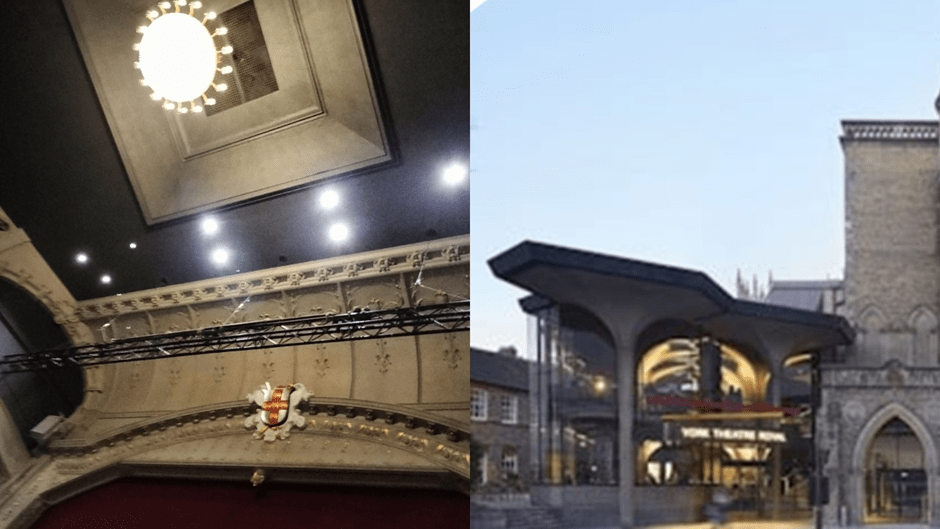

It will be interesting to see how, after seeing it in the grandeur of an old provincial proscenium theatre like York, it us will look comparatively in the more modern Northern Stage Theatre, within the precincts of Newcastle Playhouse, also a proscenium theatre but less ornately decorated and focused more on sightlines than internal décor in its conception. Of course York is a beautiful theatre – its seating gloriously raked in the stalls to offer superb views. Even though its stage form obscures some sight lines from the auditorium from some limited points, this won’t be the case at Newcastle. But the internal grandeur of the theatre tells – its framed proscenium still linked to iconic imagery and its furnishing elevated to grandeur in ceiling and chandelier. York offered me an excellent first viewing. I honour it:

In my earlier blog I said that one of the difficulties of conceptualising performance was, ironically, the beauty of the writing in Sissay’s stage directions, let alone his dramatic text. I wanted to know how to puzzle out how the intense poetic prose (poetic only in the sense of language used under tight regulation of its formal effects) might, or even could, be translated into stage action. I cited from his Foreword to the part of the play-text that constituted a theatre programme, Sissay’s praise for the innovations of Frantic Assembly itself, describing them as enacting his text using interactions between all the media available to them other than merely his words. He describes that union and interplay of effects as the ‘bond of light, sound, words, movement, dress and environment’, and goes on to say: ‘Like an animated conversation with a close friend, it is a challenge to see where movement begins, and words end’.[1] What he means by this could not have been imagined by me without having seen, as I have now seen, how Frantic Assembly works. In that earlier blog I queried another of the stage directions and I want to take in particular one which helps me to tie down some features of the stagecraft and theatre work of the company, even before considering the use of their collective bodies in co-ordinated movement with each other. I said there that some stage directions had to be:

… seen or otherwise metamorphosised so that the audience can know both them and their communicative intent, which is far from transparent, at least to me. How does MR SAMSA, played by Troy Glasgow, interpret this direction about the events around a breakfast before leaving for work and how does the stage set change in order to make the intent of it realisable to an audience, especially those below I render in BOLD. Are the changes physical or effects of light or of changes in the acting company’s behaviour in relation to stage conventions:

(MR SAMSA) eats, drinks. Slurp. Nom. He leaves for his job from his chair. Does not kiss his wife. Each family member could leave through the walls. They are becoming the house. Only GREGOR and MRS SAMSA remain. She leaves the door slightly open. The house is breathing. Everything is tightening too. Shrinking. Evening returns. …[2]

That is unimaginable I argued. But stagecraft means imagining anew by a whole raft of artists working in cooperation. Before then trying to reflect back on how this is staged in the production, lets look at the configuration of the stage itself as we see it before the play starts and before some of the effects it will lend to other theatrical play.

Within the frame of the proscenium arch is an inner frame much like a secondary proscenium raised above the stage floor and a few yards from the front of stage. This primary acting arena will represent Gregor Samsa’s bedroom. In the secondary area in front of the stage set seen above will be housed scenes of characters interacting with each other in places outside the bedroom but not always the same. Sometimes it represents other areas of the Samsa residence, other times external scenes to the whole house and possibly in the workplace or city. There is a very good illustration of this in a still which shows the Samsa parents front stage talking to the Chief Clerk of the fabric company (and the man who controls Mr Samsa Sr.’s debts) in a place representing space elsewhere in the Samsa house where Gregor’s animal like sound (represented by queering music playing over words only he and us as audience are meant to hear) can only be heard, while the audience observes his insect-like writhing within his room through the invisible wall, which is not invisible )yet) to other characters.

But space is flexible – any of it to represent remembered or imagined space, the place of interactions which may not have happened in a physical sense. The space which is Gregor’s room already tells us that much of what we are going to see will be play with visual illusions of different kinds – in the casting onto the walls of lights and shadows, the displacement of furnishing and other properties.

One particular property used is a painting (see to the viewer’s left of the bed above) of a woman arrayed in fabulous fabrics which she holds out with her arms to make a background behind her. This picture is addressed by Gregor in the Kafka text and the playscript but also becomes important to Gregor’s sister, Grete. Fabrics which play a large part in the play, for Gregor is a fabrics salesman, having taken this position from his father and to pay off the latter’s debts and to feed the Samsa family. They are part of the discourse – as both traded, usable in the form of bed-sheets and decorative items for wear. The role of silks ties to the insect theme too. Many fabric lie about the room and are variously worn to ape the posture of the lady in Gregor’s bedside picture. Thet too play a role in transformations through acting, movement and mime that compare the fantastic metamorphoses of the action of the play to those everyday ones in the art of costuming for a role, and not necessarily a role in the theatre. But the walls of the room too, we shall see are made of fabric covering a rigid frame that can at time bend them into folds.

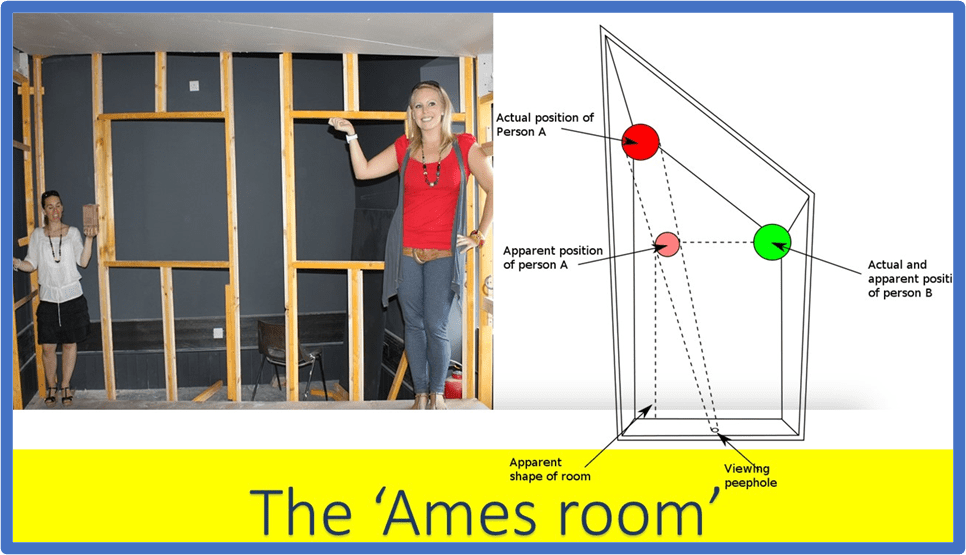

The room highlights illusion because it is formed structurally like what psychologists call an Ames room, used to illustrate size illusions caused by unacknowledged perspectival differences in space. The link will explain further and perhaps even the collage itself below, in part from that link, will be enough to get the idea.

Ames room (the effect emphasised is by no means as apparent in the play.

The Ames room, so well known even to popular psychology, is an illustration of our ability to understand simultaneously that illusion can create apparent realities out of merely physical distortions which become unobserved even to the eye that may know that they are there. It is about the role of fantastic perception as a means of sometimes seeing the world, even where alternative stronger explanations exist. This is why I think the structure od Gregor’s room is a kind of Ames Room and that is observable to us before the play starts. It both enables illusions of metamorphosis – of observed size change for instance of a minor kind in motions across that inner stage – and makes us aware that they are precisely that: ILLUSIONS. For illusion and delusion, and the roles of both imagination and perception together in this, are central to the play, not least in the fantastic beliefs that sustain institutions like family, commerce, fashion, sexual interaction and capitalist economies of exchange. How then can we look back at the stage direction I cited before. To do so let’s look at yet another explication of the stage set. The collage below labels sections of the stage craft essential to that stage direction so that its poetry sadly takes on the practical and pragmatic purpose I before found missing from it.

All that it mat be possible to understand from this is that set design is not innocent of a role in the representation of effects that create meaning from our text or translate stage directions. Let’s look at the stage direction again:

(MR SAMSA) eats, drinks. Slurp. Nom. He leaves for his job from his chair. Does not kiss his wife. Each family member could leave through the walls. They are becoming the house. Only GREGOR and MRS SAMSA remain. She leaves the door slightly open. The house is breathing. Everything is tightening too. Shrinking. Evening returns. …[3]

This direction occurs in at the time when owing to Gregor being unable to work for the family, his father must work again. Through a series or repeated cycles of movement and minor dialogue, the Sama; s repeatedly mime the repetitions of the daily grind of work that form a set of scripted behaviours (eating breakfast, kissing ‘the wife’, hugging the daughter, going to work and then returning, kissing ‘the wife’, and hugging the daughter again and receiving supper. But these repeated behaviours show the decay of such patterns by the boredom of their habituation, tiredness and need for other stimulation (represented by the introduction of alcohol to Mr Samsa). As these metamorphoses happen, so the family are ‘becoming the house’ – indicated by the tendency of the actors to begin to ignore the ‘invisible wall’ of Gregor’s room and to act through it in collaborative mimes or just by using to access or egress from the room without using the visible door and stairs. They are, as it were in illusion part of the structure of the house, even its walls. There is a particularly wonderful illustration of this in this publicity still, where the family attempt to prevent Gregor from so falling forward in his restless leaping, part of his insect metamorphosis, that his body violates the invisible wall and falls through the ‘house’. This is the illusion of the representation of reality queered and it is incredible:

The illustration of ‘The house is breathing. Everything is tightening too. Shrinking’ occurs by the fact that the fabric walls are agitated by differential twisting between the turning base of the inner stage and the fixed ceiling. The fabrics literally shake and bosom out sometimes (using mechanism I do not yet guess thereof) and the twisting of fabric into folds represents tightening.

If the stage-craft of the environment can thus contribute in bridging the gap between words and movement (the movement of things and venues-in-space) even more does acting and the utilisation of group and individual mimed movement handle the concept of metamorphosis of words, ideas and things together with these effects. The cover of the play text led me to believe Gregor as insect would be played in a costume of incredible fabrics such as the text hints at. Remind yourself then of that cover, which is the publicity image on theatre posters and advertising:

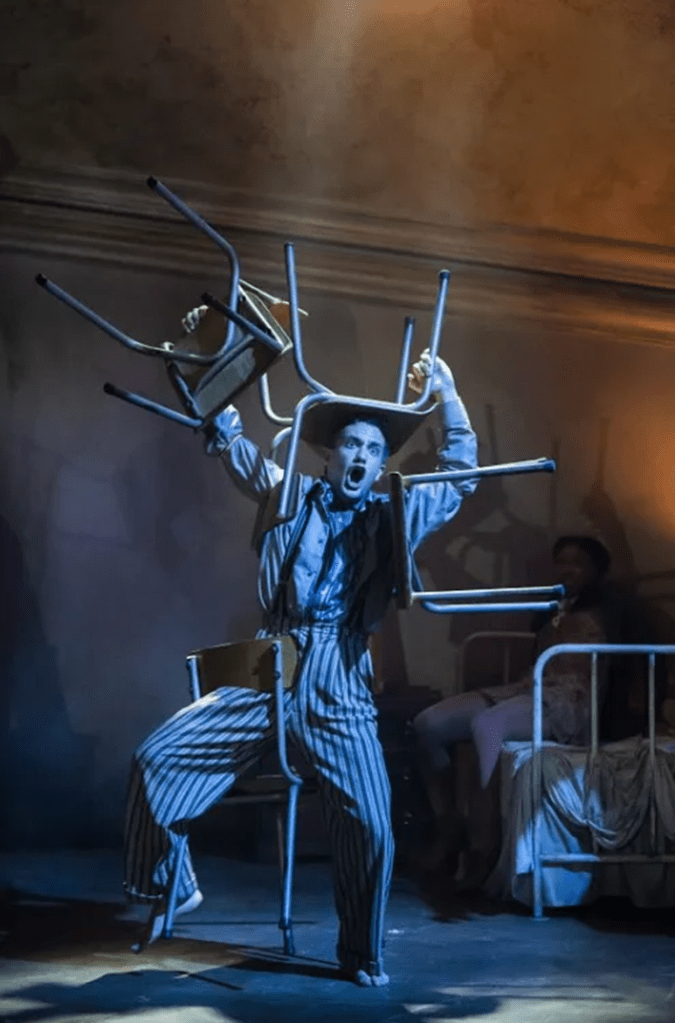

But this is not how the insect metamorphosis is indicated. Instead the actor continues as human in shape, but for the supple sinuous nature of his body movement, within or under bedsheets or other fabrics bit often without these too. He shifts with speed and aided by lifts from other cast members that flow like music, to hang from the walls on the representations of the room cornice mould, or on inverted furniture like the bed stood on its head or wrapping his hands such that his finger are so many feelers creeping and crawling round the back of the armchair when that back is turned to face the auditorium. We see him as insect first suspended from the lightbulb flex, which elongates when necessary to represent something like web or discharged silken cord (or a noose).

And what produces metamorphosis is as much the words, sounds and mimed movement, gesture and attitude of other characters as we see here the cunning use of lighting to cast shadows with metamorphosing shapes – see the hideous shadows in the publicity still above like moth wings), Even very simple effects create this illusion. The Samsas often ‘defend’ themselves from the creature that is their (adopted) son by holding the legs of a chair up to him, but at one point, they decorate his body with these chairs such that the outward pointing legs look like so many projections from the insect body.

This is an image that carries pathos, humour and fear – it queers our response. Audiences feel uncertain of their response or what it ought to be which is why I had to guard myself from seeing the responses of so many adolescents in the audience as inappropriate, for nothing, quite, is ever appropriate: Gregor above is horrific but also fearful and boxed in. One chair makes a lid to his head for instance. The imagery of the surrounding chairs offering multiple simultaneous readings depending on perception but also depending on the reactions of others including stage characters. See for instance the rather changed effect in the publicity still below:

The chairs have been agitated from the boxed in position and the insect is using them as instruments of defence, or possible attack. Hence the Head Clerk enacts a submissive gesture, though Mr Samsa is rather more puzzled and conflicted, at this point at least. And, course the shadow cast on the wall is a brilliant subsidiary showing a thing that could easily be a many-legged creature. And those shadows note multiply and deepen across and round the room varying with lighting density and colouration as well as direction.

Sometimes the effects are of mixed pathos and disgust, as especially in interactions with Grete. In the publicity still below we see one of her attempts to feed Gregor – here still as if she cared for him.

The intercommunication comes entirely from athletic motion and the proxemics of bodies and gestures. But even with just elements of stagecraft and the manipulation of physical set and properties, projected light and cast shadows metamorphosis can happen, as in the pictures collaged below of Gregor at his athletic best, and most insect-like.

At other times the interaction is entirely a kind of symbolic group gymnastics effect where the product is as much in conjoined shadows on the wall as the shapes made by the social body made up of different discrete movers.

But in my last blog I also referred to the ‘most pressing puzzle’ of the text and it needs dealing with before I move on, Whilst the Sissay family discuss the disappearance of the actor playing Gregor (Felipe Pacheco) in that final scene, Gregor is increasingly said to have ‘gone away’ and I wondered how this was done. In fact it happens thus. The Samsas make Gregor’s bed under the sheets of which he hides, at first a visible but distorted lump. They pat down the shapes he makes in the sheets, Eventually the hold up the top sheet to relay it. When they do the bed is flat. Pacheco has exited under the bed not to be seen again in the play itself. It is a very moving and quite cruel moment, especially in its relation to adoption, for the house is renewed with Gregor remaining only as a memory of vermin that needed removing from a decent house, as the one time lodger remarked as necessary (see my first blog).

The lynchpin of Frantic Assembly work and the reason for its attraction to Sissay, according to Arifa Akbar in her Guardian interview with poet and company together while the piece was in rehearsal was the aim to create an art that was bound in the physicality of bodies, buildings and things (that which we call ‘properties’ in theatre) and what these represent – in the world of the imagination or the socially real world of work and exchange. Scott Graham, the artistic director of Frantic Assembly saw that this play, and the novella that supported it, were ideal for the visceral reality of relationships between families – even ones created from entirely non-biological bonds – that Lem Sissay was able to capture from his own experience in child care, including pre-adoptive foster care. According to Akbar both came together over the idea that ‘Dysfunction is part of the beauty of family’. [4]

Scott Graham, left, and Lemn Sissay. Photograph: Adi Detemo From Arifa Akbar (2023) “‘This family is being devoured’: Lemn Sissay on why Kafka’s Metamorphosis is a tale for our times” In The Guardian (Mon 11 Sep 2023 10.41 BST ) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/sep/11/lemn-sissay-metamorphosis-kafka-frantic-assembly-insect

For both Sissay and Graham however the issues of family (especially the articulation of sex/gender and the issue of working for a living and thus sustaining the body) are networked into socio-economic and political systems and the things that represent them, as I in part explored in my first blog. Akbar cites Graham thus:

Kafka’s absurdist tale, whose protagonist is unable to go to work due to his sudden, shocking metamorphosis, is very much a story for today, they say. “This is about modern living,” says Graham, “and an economic system which invites you into debt and then squeezes you. The moment you can’t pay it back, you’re not worth anything. Gregor is dealing with the pressure to provide for his family but also to repay debt.”

Sissay himself takes this further in the same interview, explicating the eating and being eaten imagery also dealt with in my first blog, and before I read this: “This family is being eaten. They are being devoured and they cannibalise themselves as well – feeding off each other.” And work too is a form in which people eat off each other’s living energies in capitalism, where exchange systems operate everywhere. This is why the still above of Grete feeding Gregor is so moving. It emphasises both food, the caring act of provision and of taking food that hides some of the dysfunctional physical systems underlying such moments. In that picture we see the physical directly in the physical expenditure involved in living for Gregor as a dependent insect.

Frantic Assembly as a company for whom acting work is precisely that – visceral hard labour done co-operatively about the dangers in which work becomes privatised and self-absorbed, unaware of the fact that life is being sucked out of you by others – the bloodsuckers and vampires that run through the play, even Grete’s violin which bites her neck, for art is work too. Below we see the company rehearsing their impossible (or so it seems to those of us estranged from gymnastics) events.

Rehearsing Metamorphosis. Photograph: Adi Detemo in Akbar (op. cit)

Strangely enough Frantic Assembly’s physical theatre was born Akbar reports by the need to retain men in the field of the theatre, and to create a bridge between theatre and the sports that were usually, in Scott’s youth, the preserve of men and seen as masculine, and linked to the demands of what was then masculine work. But the take on masculinity in that process becomes critical of the binaries those assumptions fed off, and he and Sissay saw this coming together of that which was critical of patriarchal gender binaries and work in patriarchal and top down management of capitalism, associated to patriarchal hierarchies in family and work.

In Graham and Sissay’s hands, the story of Gregor Samsa is one that explores masculinity too, in particular how it intersects with capitalism, patriarchy, mental health and breakdown. “It’s about what the patriarchal structure does to men,” says Graham. It is not just about the love or hate of work, adds Sissay, but about the burden of being a breadwinner. “I grew up in a mining town,” continues the writer, “and the miners didn’t like going in the mines. Mines were shitholes, horrible places to work in – but they would fight for the right to work there.” The hardest thing for a man in that situation, says Graham, is to put his head above the parapet and say: “I don’t want to do this.”[5]

In this context, we should look again at how theatre tells us about how even the work that deals with dreams, fantasy and the imagination saps life, and often does it by ignoring the fact that bodies are vulnerable to the power of others and their imaginations – as Gregor is a fabric salesman imagining the women he sells to in the clothes he sells. This imaginative danger, is I think, embedded too in the incest theme – for incest tears apart the structural issues on which families of workers and feeders both co-exist in contradictions. Grete’s fascination with Gregor feeds off her fantasies of work she will never afford to do without him – training as a professional violinist. It can only be done by being as parasitic on Gregor as she imagines her violin is to her, or Gregor is to her once she becomes his carer rather than vice-versa. Incest explores this in deep symbolic connections that are intrinsic to family, until Grete becomes a commodity for the marriage market at the end of the play.

This is as far as I can go on this subject now but who knows what another viewing of the play in another theatre will reveal. Roll on October 26th.

Northern Stage in Newcastle University Campus

All love

Steve

[1] Lemn Sissay 2023 op.cit: from unnumbered theatrical prefatory pages in the Writer’s Note.

[2] Ibid: 45.

[3] Ibid: 45.

[4] Sissay cited Arifa Akbar (2023) “‘This family is being devoured’: Lemn Sissay on why Kafka’s Metamorphosis is a tale for our times” In The Guardian (Mon 11 Sep 2023 10.41 BST ) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2023/sep/11/lemn-sissay-metamorphosis-kafka-frantic-assembly-insect

[5] Ibid.

For a variety of reasons I have been unable to get out to visit the theatre for a while, I want to thank you for this critique as it is perhaps the closest that I could actually get to a physical performance as well as providing a detailed and comprehensive analysis of the play, the performance and the staging. I know that I will return to this for a slower more intensive read at a later point as I know it will yield food for thought (no pun intended). Thank you again.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kes, I think we would make perfect theatre-going friends. X

LikeLike