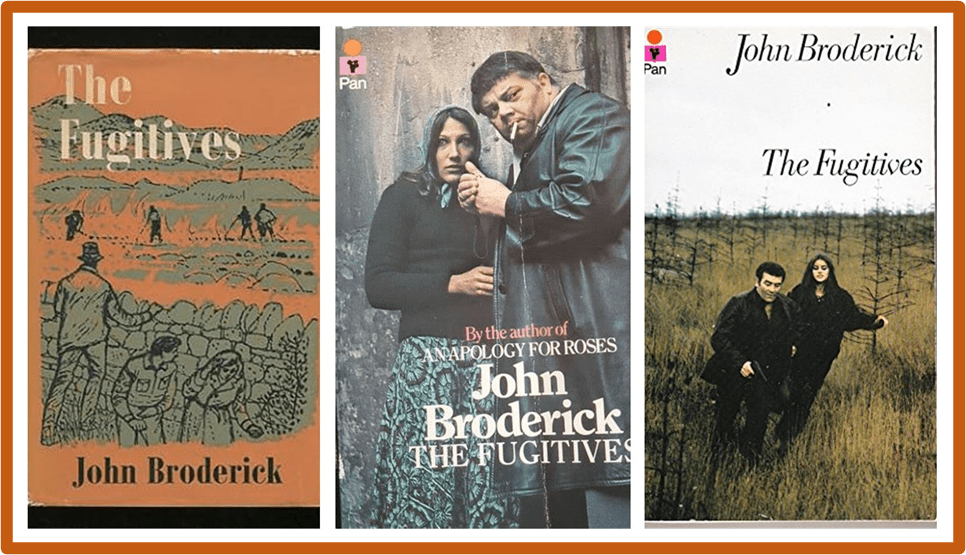

The Fugitives (1962) by John Broderick tells stories of people who flit around at the margins of a world they resist and would like to change: ‘A world in which death slipped easily, like one of those midland corner-boys edging through a pub door, dead of foot, buried of hand, mortified of mind; a familiar sight. / It was a waiting world. … Something indefinable, far back in their blood, derived from the flat passive fields that bred them, told them to wait’.[1]

John Broderick’s stories arise out of the land and the myths of the midland plains of Ireland. These myths are not just those, though it uses those too, of ghosts and creatures that haunt the twilight world of Celtic myth, including ghosts and vampires, the remnant of Paganism debased to hungry creatures yearning again for flesh to become embodied. Such creatures are sometimes evoked as means of explaining things one can’t understand about ones present circumstances. Thus, for instance, Paddy, fleeing the Irish and British police for involvement in an IRA murder in London is taken to live in an abandoned cabin by candlelight in the bog by his sister Lily. There he will stay with his IRA minder, and would-be lover (though that is not known to Lily, who thinks she is being courted by that man for pretend, or perhaps real), Hugh Ward. The characters more than once refer to each other as acting like ‘a ghost’, and weird night-time behaviours characterise them all.[2] Lily’s estrangement from, and haunted, possibly incestuous, feelings for, her younger brother create a scene that might come from an Irish ghost or fairy tale:

…, the candlelight playing tricks with his face so that ne moment his eyes were visible and at another. The lower part of his face with its twitching mouth. He seemed a creature from another world as he stood upright in the flickering light, holding the candle aloft. Lily, unable to bear the strangeness of the scene, turned and made for the door.

Within pages Hugh Ward is being spoken of in the town as having ‘a deadly instinct for divining the weak spot in another person’s character’ that is developed to ‘an almost supernatural degree’. In case what is eerie and uncanny in this is missed, the speaker, Kate, a dying woman herself and aunt of Lily and Paddy, says of Ward that he ‘lives through other people’ and is one of those equally skilled people who are all ‘blood-suckers, vampires’.[3] Death haunts the novel, like that of the dying young mother Mrs Fagan, and it is a death that has to be waited for before life takes on again its everyday rhythms.[4] Only the ‘ritual of death’ allows the rituals of life to return.[5] So consistently is death awaited that it sometimes dooms the young and this is the fate Lily resists for her beloved brother Paddy, thinking the death instinct is represented by Hugh Ward and now fighting ‘for her brother’s life’ by seeing Hugh’s association with the deadly history of the Irish cause against British rule and War’s sexual passion for him (about which she has now guessed and which she sees then as ‘filthy thing he was looking for’ as itself the emblem of the death awaiting him.[6] She has become in contrast a life-force like that represented by Bernard Shaw as Nietzschean in Man and Superman.

In being so I do not think she is validated or her behaviour seen as authentic, as Shaw does seem to validate the concept, for Ward and Paddy are correct that she has too thin an idea of Irish history and its specific struggles, and the role played in it by random death. Moreover, she barely understands herself how to resist the lure of the deathly fascination with an English occupation of her soul and sexuality. She is, I would say Broderick’s tortured picture of the Catholic Irish who abandoned Ireland for London or other English cities, for they feared standing up themselves for Ireland, or even the dignity of their own bodies. Broderick is terribly hard on her in this respect. Ward, who is both the principle beyond good and evil at times says of her:

“You’re like all the rest of them here,” he insisted. “It’s all a vague dream. You dream about it and you read about it, but you’re afraid to do anything about it. Who ever said the Irish were wild and romantic? They’re afraid of their own shadows. You’re even afraid of your own image in the looking-glass.”[7]

Shadows and mirror-images are part too of the Gothic machinery of the novel and many characters see themselves in fantastical doppelgänger forms in these manifestations of a second self to the eye. Indeed Hugh Ward had himself had this experience in his hotel where the ‘small room was as cold as a church crypt’, which though ‘shadowless’ because of the ‘naked bulb’ of light in it caused by its glare a ‘distorted’ form of himself in the cheap ‘looking-glass’.[8] Broderick’s narrator, with a voice as omniscient as is George Eliot’s sometimes, has also before found that people create illusory selves that queer their sense of reality, if not destroy it. We should note though that though distorted by illusion the looking-glass selves in the following of both Aunt Kate, who thinks herself a kind of anchorite nun, and Lily, who sees herself as a modern sensual woman as do the women in Shaw, do not see the whole of reality but see an equal degree of it. That is those doppelgänger selves are not invalid, just not the whole story that is to be seen, and this is how we must read Broderick’s take on the life-force later and her equal dismissal of the deadly in Irish history and British oppression as well as her view on homosexuality, which is surely a sick one, no better than Hugh Ward’s which she condemns and as full of deceit as his, for what she never admits is her sexualised desire for her brother: ‘All illusion is self-illusion. Lily, blinded by her romantic dreams, was no more cut of from reality than the keen, intelligent old woman. When we gaze in the looking-glass we do not always see ourselves’.[9]

Lily is very different from the sexually enlightened and free women in other Broderick novels, who like Julia in The Pilgrimage embrace the fact that feminine sexual desire is as misunderstood in the status quo and as marginalised as that of queer people (see my blog on this). Lily never quite understands that that identity is formed in the crucible of power relations and her response to fear is always to succumb to the oppressor, which is what it means to become a part of the London Irish, as Broderick himself did, though he decamped to Bath. This can be the only meaning of that ponderously queer rape scene, where she gives herself to a young rapist who follows her into a blind alley, praising his sexual prowess. We never know how to read this for it is extremely chilling to me. Yet I cannot see it exonerating the rapist nor damning Lily, for to give in was the only safe thing she could do in the circumstances if she was to be certain of surviving the ideal.[10]

However, it is also part of the kind of giving way to the sexual that forever types her as locked in romantic distortions, even in an extreme circumstance, and is what takes us back constantly to the idea that her only real object of love in her life was brother, Paddy, and that this explains why, in an act meant to save him from Hugh’s queer clutches, she (perhaps) kills him in the end instead of Hugh and is incarcerated for it.[11] Broderick characterises Lily as herself a kind of liminal being, forever flitting between multiple identities on the ranges of sexual and asexual womanhood, London and central Ireland identified, sexual lover of idealist of men of men who approach her. The hardest passage then to read is this:

Too many hands had touched her face, cold and calculating, or hot and feverish with lust. Like all people who have explored the jungle of promiscuity she had disassociated love and desire. Platonic love is the ideal of the dissolute.[12]

But it is only teasing if one insists that binary contrasts are meaningful and want like Lily and some others to place desire and love as a form of this binary, instead of a mixed single reality as being dissolute is from being pure and untouchable, the cold and the hot, and, reason and passion. The point is Lily like all of us is a mixed-up and unresolved person, capable of homophobia at the same time as understanding a young male rapist and facilitating the latter, of loving and hating Ward as a reflex of loving and standing off from her brother.

Hugh Ward is fascinating yet capable of great evil. To him at times his love of country and men is a kind of game at times, as when he stands up toy soldiers in a row in order to run ‘his thumb along the line of soldiers, felling them one by one’.[13] But why he does this is never clear for this episode immediately had been that where he had approached Paddy, and clearly not for the first time, responding to ‘the boy’s moodiness and immature drunken behaviours such as giggling by manipulating his body in the manner of a lover. Paddy both resists and invites in ways that do not answer the question of whether Ward is grooming him for a sexual relationship or reassuring a young man (for that is what is meant by ‘boy’) that it is alright to feel sexual and romantic feeling for another male.

There is much of force and imposed control in Ward – he grips (an ‘iron grip’ at one time) and grasps and clutches not just holds his body, asserts rather than discusses, drops Paddy’s head on the bed rather than easing it on to his pillow. But Paddy is flirtatious too and his resistance sometimes playful: ‘The young man made no effort to resist, but suddenly began to giggle and then laugh, his head shaking on Ward’s chest’. There is ambiguity in all this, particularly given the role of alcohol in all this. There is a sense too, I think that Lily may discover at the end that Paddy is not a victim to Ward but someone cared for by him, when we sees the ‘peculiar intensity in the way [Hugh] was leaning forward and staring at Paddy’.[14] It is an intensity Hugh does not show to her and the motive of her feelings is unclear even here ‘in the damp coldness of the dawning day, watching the watcher’. The ‘dawning here is recognition of an aspect of love she has and does not experience directed to her in this novel, except as a mask, and it is cold – as calculating as it stirs warm emotional revulsion later.

I can’t then but insist that this is a queer novel wherein queerness is a construct between people in different kinds of relationship and mutual regard, where desire and love are experienced on a spectrum, as are death and life and where gradations of distinction and mix of elements matters more than simple statement of simple supposed facts. There is no revelation at the end of this novel – or any Broderick novel – only a sense of how hard to understand the world is in its politics (sexual, national or in relation to classes and status). In looking at the Waking of Willie I spoke of a beautiful use of a metaphor of groping in the dark to characterise the attitude to the old truths the novels undermine, about sex/gender for instance. The metaphor is stronger still in this earlier novel. All attempts at communication and communion at the level, as Hugh puts it, of ‘what the blind do’ for at this ending ‘it was as dark as the world of the blind’.[15] At other times this dark world is a world of the dead – that buried from our attention and repressed with the knowledge that might help us of important matter. There is a ‘death-like stillness’ in the log cabin, that conveys the ‘ghostliness’ of a liminal place.[16]

At one crucial moment the communion of bodies is merely of ‘dim shapes facing each other’. In this situation with no signs of being heard, seen or sensed, Lily is not able ‘to bear the silence any longer’ and:

stumbled forward, clutched her brother’s arm and clung to it desperately in the darkness. This was the only communication she had ever been capable of: the clinging together of bodies in the darkness. And she had no more knowledge now than she had ever had.[17]

She is not unlike Ward clutching Paddy here. It is a way of communicating that has become our only tool of being together but still yields no knowledge of what makes human beings tick and form bonds that matter and can be sustained. When I started this discussion I spoke of the use of Irish myths but it is important to recognise that this facet of the novel includes too contemporary myths, especially of the Irish as persons without fixed status, as people who cannot settle to things and as eternal migrants. These characteristics are in fact a product of their continual experience of colonisation and enforced starvation. But I have quoted one of these in my title to this blog that may have gone unnoticed, so let us quote again – the myth of the Irish ‘corner-boy’ (for it is a term used largely in Ireland nowhere else, suggesting a young man who lurks at street corners like the one who rapes Lily and the one Paddy may well have become ad he not turned to the IRA. It is near the end of a long rhapsodic prose piece about the Irish way of preparing socially for deaths, and occurs as the story is about to shift from midlands town to its boggy hinterland. Here is the quotation again:

‘A world in which death slipped easily, like one of those midland corner-boys edging through a pub door, dead of foot, buried of hand, mortified of mind; a familiar sight. / It was a waiting world. … Something indefinable, far back in their blood, derived from the flat passive fields that bred them, told them to wait’.[18]

I love those phrases whose meaning is so unclear but so precise in characterising the liminal feel of the displaced in society: ‘dead of foot, buried of hand, mortified of mind’. For if they have meaning it is merely associative and indefinite (indefinable as we are in fact told). It is about a mind and motion in which that which makes the sign of life is associated with the dead but not identified with it, something which defines a ‘national characteristic’ as do the most appalling anti-Irish stereotypes but dignifies it with something essential to humanity – the capacity perhaps to take on and understand the value of the passive as well as active in life. And it is that which breeds that old virtue of ‘patience’, the ability to wait for the value of things to emerge from dark confusion. In the novel, they never do, but I love this emphasis in a queer novel.

In my view, it is what our queer community needs – an ability to survive and wait, await not recognition but fully cocooned rights as persons, respecting our own and others’ diversity. And it is emotional maturity will come with that – not the pursuit of happiness – a feckless pursuit – but of significance without recourse to God and myth that is not essentially about the flesh, all we have. I find this quotation a good place to end, for a part of it, characterising happiness in terms of unhappiness occurs twice near the novel’s end, illuminated by real bog whin-fires:

Suddenly the world was lit up with flames: a lurid dangerous world to which she responded with every fibre of her being. Happiness was no longer the absence of unhappiness but the living of each moment as if it were her last. Every woman will aways choose death rather than the lack of love.[19]

I think this is superb. My only rejoinder is that the last sentence applies not only to women, but some men too (perhaps Paddy in the end) and me, I think. This is the secular world’s fate and hope.

With love

Steve

All my love

Steve

[1] John Broderick (1972 [first published 1962]: 113f.) The Fugitives London & Sydney, Pan Books

[2] See, for instance, ibid: 99,

[3] Ibid: 126

[4] Ibid: 111f.

[5] Ibid: 117

[6] Ibid: 162 & 167 respectively

[7] Ibid: 99

[8] Ibid: 93

[9] Ibid: 129

[10] Ibid: 133f.

[11] Discussed ibid: 169f.

[12] Ibid: 155

[13] Ibid: 93

[14] Ibid: 155

[15] Ibid: 165

[16] Ibid: 152

[17] Ibid: 162f.

[18] ibid: 113f

[19] Ibid 148(see echo on 152)

‘

The Fugitives (1962) by John Broderick tells its stories of people who flit around at the margins of a world they resist and would like to change: ‘A world in which death slipped easily, like one of those midland corner-boys edging through a pub door, dead of foot, buried of hand, mortified of mind; a familiar sight. / It was a waiting world. … Something indefinable, far back in their blood, derived from the flat passive fields that bred them, told them to wait’.

2 thoughts on “‘The Fugitives’ (1962) by John Broderick tells stories of people who flit around at the margins of a world they resist and would like to change: ‘A world in which death slipped easily, like one of those midland corner-boys edging through a pub door, dead of foot, buried of hand, mortified of mind; a familiar sight. / It was a waiting world. … Something indefinable, far back in their blood, derived from the flat passive fields that bred them, told them to wait’.”