Your life without a computer: what does it look like?

The prompt today contains, of course, its own bias. First, it speaks to people who are first asked to imagine life without a computer as if that absence could occur to one individual, regardless of the rest of the globe. Second, it sort of presumes imagining something of which they have no experience. In fact I was schooled when computers were huge interconnected pieces of hardware: so large they needed computer suites (nearly always called in remembered my imagination IBM – International Business Machines -after one huge brand version) to contain them. Even seeing one of these except on TV and in films – was beyond the experience of most except for those who worked directly with them on specific tasks.

Jean-Luc Godard imagines the computer world in ‘Alphaville’, a dystopia on film. Available at: https://www.computerhistory.org/timeline/1965/#169ebbe2ad45559efbc6eb3572027255

What follows is a set of personal memories and possibly inaccurate generalisations about the advent of personal computing, which is what I think this prompt is about, in my life historically. It is only how I saw things as they impacted me, as a boy and then young man from a working class Northern background, largely absorbed in the arts and who wrote all my undergraduate essay work manually on lined paper. The first contact with a PC was linked to the legends surrounding Alan Sugar.

Amstrad CPC 464 computer (1984)y Bill Bertram – Own work, CC BY-SA 2.5, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=133247

The bruited and fabulous wealth of Sir Alan Sugar was based on him being savvy enough to see the trajectory of the technology into minutely smaller versions with a single access point, a front screen into which input to and output from could be organised by the use of a computer language, converting the binary code employed previously by IBM and it’s like into something semi-intelligible. I had an Amstrad (the Sugar baby of personal computing so to speak) but not until I was in my early twenties.

Personal computing then took off because the front-end of computers became nearer to what we see now, though far less sophisticated by being programmed to present the ‘end-user’ with ‘user-friendly’ access. demanding from them (hence the term ‘friendly’) little or no knowledge of the various computer languages used in the construction of their iconic imagery and it’s fabulous extensions.

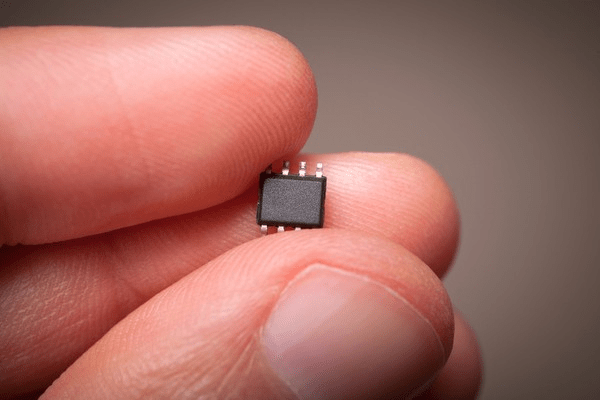

The portal to personal computing was the microchip, that minute version of the many interconnections that once needed a suite of rooms to house them. The work of the computer could be driven by a small processor linked to a small group of smaller dedicated processors to other input and output hardware, all under instruction from software now written in specific and varied code sets called software languages. I remember learning a few, stopping at Pascal, which I found difficult.

Available: https://dialoguereview.com/brief-history-microchip/

The hardware and software, of which a computer is composed and integrated, in expansion suddenly became affordable also though incrementally to individuals. Personal computing started of course with the personally wealthy, who would lead the market trends thereafter. And with that access was born too another version of the ‘haves’ and ‘have nots’, the so- called ‘digital divide’.

On a national basis the divide was represented by class, region and educational opportunity, inextricably linked of course and with other marginalisation fuelling economic and social inequality widely. Globally rich and poor nations became more divided even by these new resources that would further disadvantage these countries and actively underdevelop them, in the jargon of the day. Hence, I think here we need to remember another problematic issue in our prompt question.

It is still the case that some do not have to imagine a world without computing. This picture is complicated by the extension of the domain into smart-phone technology where that hardware and software is the means of access of even very impoverished persons, young ones at least, in Africa and the Southern Asian subcontinents. The digital divide needs to be remembered too in thinking of this issue and even though it is a very nuanced thing in the days of the smart-phone, it still follows patterns of resource inequality, nationally and globally.

We are where we are though. Trying to imagine a world without a computer is almost an impossibility for computing has so many access points and, due to the internet, so much spread, and can be accessed as a public resource, in some economies, as well as a private one. It need not be personal this ownership. If one visits any institution and even if you never access them yourself, you are connected to computing because many contain and can distribute data about you and collect more, sometimes without your intervention or permission, as in the car of huge state organisations or multinational companies like Amazon.

We can never cut ourselves off from computers, though we may be economic with the means by which they are allowed to be visible in your life. They are increasingly vital in personal transactions even in the private and voluntary sector. They are used to access buildings and record our presence there or to buy and sell or access cash, which they increasingly make less necessary.

Hence, even if we decide to limit computer time personally, the absence of a computer remains is as virtual as the world seen on a computer screen, the operations of computing deal with our data continually and without break, even when we sleep. This is the root of the fear of AI, where a computer gains the capacity to make decisions based on no need for human permissions except in extreme or rogue circumstances. And then the computer it is who alerts us of such circumstances. We can take this fear too far no doubt, but much remains unimaginable except by sci-fi, which often gets it wrong. Remember Robbie the Robot.

So no direct answer to the question here again, but some thoughts at the least. And maybe Google does know the ‘Meaning of Life’, but if so, that’s not a reason for hope.

With love

Steven