‘We raised him and we saved him and when he was old enough he accused us of keeping him from becoming his … true self’.[1] This blog is a preparation to see Lemn Sissay’s Kafka’s Metamorphosis, an adaptation, retelling (and more) in a new dramatisation of Kafka’s Metamorphosis with the company Frantic Assembly with more than a glance at Sissay’s memoir My Name Is Why, for that book underlies the dram too. I shall be seeing it at York Theatre Royal on Thursday October 12th at 2.00 p.m.

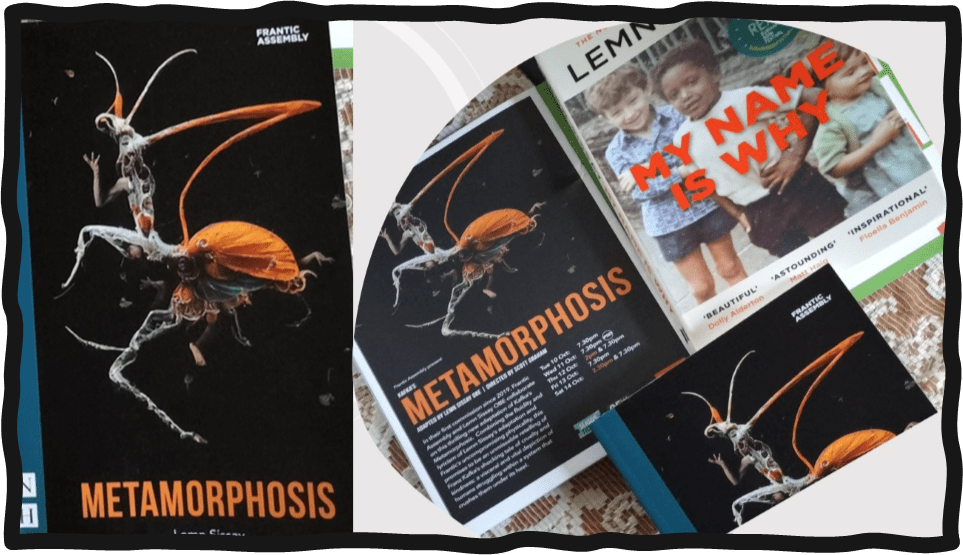

I particularly wanted to prepare for this production for I could not imagine a theatrical version of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. Moreover, I had just been reading Sissay’s memoir My Name is Why. I had not foreseen that this too would help me understand Sissay’s text for Kafka’s Metamorphosis. However, as I was to find reading the text is not preparation enough for certain elements of that text keep secrets about the dramatic handling of the story and its cast of characters. The most pressing puzzle concerns the fate of the actor playing Gregor (Felipe Pacheco) in that final scene for no indication appears in the text of where he is or goes after the intense incestuous (surely at the root of his ‘insectuous’ nature as we shall see) play described in the stage directions:

GREGOR thinks he is alone with her and that MR SAMSA and MRS SAMSA are concerned with seeing the LODGER away. He is entranced, He moves close to her and away. Close and away, Close. He wraps his arms around her and draws her to him and kisses her on the neck.

Then we cannot know what Gregor does. We know the family move away and move Grete (Gregor’s sister and the ‘her’ referred to in the stage direction above) away too and stand in a stage space supposed to be outside the room in which those silent manoeuvres occurred but where is Gregor in the total stage space? We aren’t told. When I see the play I will want to know and test the effect of any option on the dramatic dénouement. When he is again mentioned, it is as if Gregor were no longer visible on stage, as ‘Outside the room, the others begin to construct the narrative of how and why GREGOR went away)’[2]. The presence and absence then of the actor playing GREGOR will cause different kinds of interpretations to emerge; ones that make ‘visibility’ a complex version of what it means for the marginalised to feel invisible, whilst they are in fact bodily present. Even the discussion of Gregor going away recalls the behaviour of Sissay’s own foster parents who ‘were determined to wipe me from their family story’.[3] Grete too, as a woman in a patriarchal family says of that family that sometimes she feels that ‘they don’t even see me’.[4]

How are we to know how the nuance of this will be enacted until we see a production and I hesitate to read reviews lest they cause disappointment by giving the process away. But this is not only because of the absence of clarity as to where the actor is in the text’s scripted dialogue and poetic stage directions, but also because the stage directions are themselves beautifully written, and an intense prose poetry, and full of effects in word and phrase structure that must be translated into action. However, how, exactly will that happen? What we do know is that Sissay makes a point about the way in which the theatre company performing this play (but only in rehearsal when he wrote this), Frantic Assembly, play on the cusp between and within the ‘bond of light, sound, words, movement, dress and environment’. So much is this the case, he says: ‘Like an animated conversation with a close friend, it is a challenge to see where movement begins, and words end’.[5] But when the ‘words’ are stage directions, what is the nature of the movements indicated to actors in these words: ‘He moves close to her and away. Close and away, Close’?

Even more interesting is that stage directions are in no way transparent and written as if to be heard, seen or otherwise metamorphosised so that the audience can know both them and their communicative intent. How does MR SAMSA, played by Troy Glasgow, interpret this direction about the events around a breakfast before leaving for work and how does the stage set change in order to make the intent of the stage directions realisable to an audience, especially those below I render in BOLD? Are the changes physical or effects of light or of changes in the acting company’s behaviour in relation to stage conventions?

(MR SAMSA) eats, drinks. Slurp. Nom. He leaves for his job from his chair. Does not kiss his wife. Each family member could leave through the walls. They are becoming the house. Only GREGOR and MRS SAMSA remain. She leaves the door slightly open. The house is breathing. Everything is tightening too. Shrinking. Evening returns. …[6]

What is clear is that alienation is an effect that occurs in both the content of this play and its theatrical production, a constant shifting of assumptions not only about what constitutes a social norm but what constitutes the thing we call ‘reality’, which never seems graspable. This is especially so in relation to the process and duration of ‘real time’, for time is constantly speeded up or slowed down (even ‘frozen’), unevenly so sometimes between different sets of characters. It’s yardsticks are the shape of the day as divided between shades of light and dark, the schedules of work and home times, the schedules of transport (notably trains) and the economics of time in the structure of commodity markets and especially in the concept of being ‘on time’ and ‘late’, for Gregor’s story in Kafka hangs on the fact of being late for work, and the train to take him there and the ruptures in reality this appears to cause for him and his family. But lack of time is also oft used an excuse for failing to care for others.

After all, we all say we are ‘busy’ to avoid commitment. Grete says it of herself and her parents to excuse the neglect of Gregor – a speech that seems full of the experience of being fostered by people thought to be one’s parent-carers: of her parents Grete says that they ‘are tired and we are working like slaves, to what benefit? To whose benefit … We would give Gregor more attention if we had the time’.[8] The ultimate explanation of how time is treated is as a form of capital, a resource owned by capitalists and used to ensure the timely transport of things between places and controlled as a means of owning in the interests of the capitalist the bodies of their workers. The Head Clerk’s poetic evocation of the time economics of world trade is used to tie Gregor to his time contract for, in his abstract of that long speech that precedes it: ‘Time is money. There is none to spare’.[9]

And time is also a kind of conundrum for though we can feel that custom and schedule make everything seem the same through whatever duration we pass, it insists that its passage is from one moment to a different one, even if that second moment is identical to the first. In the life of a salesman, Gregor sees this dialectic of sameness and difference constantly in play: ‘Today is the day. Every day is different. No sale is the same. Different day. Same sale. Same day, different sale. Same sale different customer …’, and so on.[10] And yet, at the heart of Gregor’s ‘waking dream’ (from the stage direction) is a metamorphosis of the stuffs of his days (which are the fabrics he is engaged in buying and selling) into something rich and strange, something imaginative and full of unspoken content – as in this horrific image that prefigures the kind of metamorphosis he will himself undergo:

A face of. Cloth moths, fields of braided silk gloves … the sky was a bloodstained satin … then a giant long patchwork face with different squares of skin and lips sewn together pushed through the clouds down to me and it was trying to speak.

In this fantasy there is not only fabric and fabrication but the transformation of the work of insect lives into the fabrications of human dreams – of being singled out for instance for attention by a grand god from the skies wanting to speak just to you, and perhaps also something threatening that has been silenced and may silence you – the painful image of skin and lips sewn together predominates here. Grete too fantasises about such threatening wordless joys of being paid attention that feels sexual in nature, and are from the first associated with Gregor as incest is to the insect he will become. It is embodied in her violin which she imagines as having the ‘fat body’ of an ‘insect’ and to drain her blood at the neck like a vampire: the association of insect and vampire is, of course, the content of the last episode of interaction between her and Gregor in the play, wherein he ‘wraps his arms around her‘ (he is an insect at this point note) and draws her to him and kisses her on the neck’.[11] It is a sexual fantasy of course.

How like her violin is Gregor, and not only because the instrument always enraptures him, as it will the fee-paying male Lodger at the end of the play (there are three male lodgers in Kafka’s novella): ‘It is an insect and its fat body is filled with my blood. … My violin is an insect and it is sucking the blood from my neck into its body’. She says of her violin that this ‘bloodsucker in mine’ early after Gregor’s metamorphosis into an insect, where the term MIGHT apply to him.[12] Indeed MR SAMSA sees Gregor too as a ‘bloodsucker’ in that he becomes economically non-productive and a drain on the family’s living, his financial incapacity being treated as ‘selfishness’: ‘All to keep this … Vampire. They are sucking my bloodaaacchhhhh arcgghhhchhhhh’.[13]

Moreover, Gregor here is the very symbol to his father of the economically inactive – the scrounger, the ‘beggar’ who wishes to alienate from themselves – see him as distinctly alien, as Sissay himself was by his foster-parents, and for which reason he sued Wigan Social Services. cannot be a chooser because they are dependent.

MR SAMSA makes Gregor into a kind of Heathcliff – the possible beggar son of a prostitute (perhaps one he has purchased sex with and perhaps, we are to learn, the reason for his relationship to GREGOR). But there is more than fantasy here, there are all the mechanisms by which a child is made to feel alienated from a parent (a foster or biological variety thereof). That beggar or prostitute woman is seen as being herself as disgusting as an insect, when, for instance, ‘her emaciated body elongates from the concertinaed position needed to beg’ and he sees ‘ the exposed bone where her foot should be’.[14] It is certain too that MR SAMSA sees his wife as a kind of parasitic insect, forcing her constantly to fear having herself to work for money.[15]

This theme of economic parasitism, that sometimes segues into consideration of the role of sex in adult capitalist and patriarchal economies is dealt with too in the plays view of the imperative to eat to live, and the metaphor of some persons who are no longer eating to survive but feel that not only are providing food for others but are that food. MR SAMSA warns his wife that she will ‘go ahead and be eaten’ by Gregor if she enters his room rather than the trusted Grete. His story of the beggar woman previously mentioned is eventually revealed at its end to be a fiction showing Mr Samsa’s belief that the true bloodsuckers are his employers but one he is not allowed to talk about by the Chief Clerk. When the parents and Grete turn against Gregor they reduce him to a commodity and to be punished by being treated as food for a painful process of cooking alive:

MRS: … turn him on the spit.

MR: Slide it up his ass and out his mouth, be done with it.

MRS: Keep him alive I want to hear him scream and shout.

…

MR: let’s internally flood him.

For bread and blood pudding.[16]

The nastiness of the fantasies of bourgeois families knows no end in Kafka nor Sissay, for both had experienced it. And I think this is because both want to expose the myth of the work and /or home as a place of safety and security. Jobs are never secure in Kafka and are means of imprisoning the self, as both MR SAMSA and GREGOR are by the same employer who entails them by inherited debt. Homes depend on income and their walls fail to be secure.

MRS SAMSA knows middle-class women have sometimes found themselves on the streets because of the unreliability of fathers and husbands: ‘In the blink of an eye she is begging on the street with a baby at her teat. … And there is no pity’. Under the ideology of eternal love lie the reality of hunger and the scratching of th rats under a decaying house. We are all ‘sniffing weakness and poverty’.[17] Walls seem like security, when they don’t imprison (which they also do), but Gregor who as an insect crawls all over them leaving brown stains, knows walls have to be silent, for if they spoke, they would tell the horror stories the bourgeoisie hide under them or behind them of sexual rape of wives and children and abuse of the vulnerable cared-for:

If these walls could speak, they would not. They would wail from all upper corners, wounds for mouths, each one of them, and drool as they tell of night visitors, dagger-toothed ghouls, ….[18]

I think I need to see the show to see how all this works as theatre, where sets must suggest real walls and homes and workplaces but also fantasies of social, economic and moral decay of family and the familiar, the true uncanny – the difference within what seemed the same, the unfamiliar (and frightening) within the supposedly familiar. The Lodger in this story takes this theme into the idea of house retail where appearances mask horrible realities and insecurities that have to be covered with house paint and the ‘tired floorboards’ replaced. The worst image of bourgeois social insecurity is the fear of insect attack: ‘Get it debugged. The moths might stay away’. No doubt the fear is that time exposes appearances to test and commodity value fears its own decay, like the fabrics which dominate this play.

But let’s stop here. Next week I will see the play and have much I hope to report on How Frantic Assembly deal with the nuance and deceptiveness of this play – its insistence that reality is the greatest fantasy of our society and that metamorphosis is going on all the time, about which people need to pretend. That is, of course, one of the facts of The Story of Why. Lemn (the name translates as ‘Why’) loses his name to become, in bourgeois terms normal NORMAN. Exposed to young, marginalised lads in a children’s home, he is not normal at all, as he realises when he attempts to shake the hand of Jack who speaks as unintelligibly to Norman as if he had been from another planet: ‘So who da-da-da-da-da are you, da-da-da fucking hell’:

I know how to hold my knife and fork. I keep my elbows off the table. I say please and thank you. It’s not me being devious. It is what I am trained to do. Jack stared at my outstretched hand as if I were an alien [my italics].[19]

‘As if I were an alien’, or an insect or A MONSTER, something no decent person (by one’s own familiar standards and conventions) could live with for the more we look at it, the more we see what we unconsciously want to believe it is:

MRS: It’s a monster. It was always a monster.

MR: Not part of this family.

GRETE: We must get rid of it’.[20]

To tell truth, this seems to me a play I must see. And I will NEXT THURSDAY.

And then I will add to this blog or do a sequel.

All the best & with love

Steve

[1] Mr Samsa speaking in Act Two of Metamorphosis, near the very end of the play and after changeling son Gregor’s disappearance. Lemn Sissay (2023: 55) Kafka’s Metamorphosis London, Nick Hern Books Ltd.

[2] Ibid: 54f.

[3] Lemn Sissay (2021: 112) paperback ed. My Name is Why Edinburgh, Canongate Books

[4] Lemn Sissay, 2023 op.cit: 12

[5] Lemn Sissay 2023 op.cit: from unnumbered theatrical prefatory pages in the Writer’s Note.

[6] Ibid: 45.

[7] ibid: 48

[8] As in, for example, ibid: 16f.

[9] Ibid: 23

[10] Ibid; 7

[11] Stage direction, ibid: 54

[12] Ibid: 31

[13] Ibid: 46

[14] Ibid: 37

[15] ibid: 41

[16] Ibid respectively: 43, 38, 33

[17] Ibid: 39

[18] Ibid: 19

[19] Sissay 2021 op.cit: 76

[20] Sissay 2023 op.cit: 55

شكراً

LikeLike