Wikipedia is, as always, helpful, wherein on the subject of ‘Human branding’ it says:

Human branding or stigmatizing is the process by which a mark, usually a symbol or ornamental pattern, is burned into the skin of a living person, with the intention that the resulting scar makes it permanent.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_branding

A further extract on the use of branding of human beings used in the practice of slave owners in the South of the USA says:

In Louisiana, there was a “black code”, or Code Noir, which allowed the cropping of ears, shoulder branding, and hamstringing, the cutting of tendons near the knee, as punishments for recaptured slaves. Slave owners used extreme punishments to stop flight, or escape. They would often brand the slaves’ palms, shoulders, buttocks, or cheeks with a branding iron.[11]

For the modern usage of the term, Wikipedia uses a different entry for the term ‘brand‘ standing in its own right, which it defines as ‘a name, term, design, symbol or any other feature that distinguishes one seller’s good or service from those of other sellers’ (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brand). This definition concentrates upon a brand that is instantiated in things such as a symbol, logo, or other ‘markers’ of origin, including characteristic sounds or tunes, which determines in the mind’s eye of potential buyer a particular version of a commodity or range of commodities. It is the very lynchpin of commodification in modern capitalism and begins to have a market value distinct from the product itself very early in its history. This is best symbolised by one from my childhood which made clear in its jingle that the consumer is being asked to buy the brand as both a substitute for, and doppleganger of, the original simple substance of which it is a form: the phrase being ‘Beans Means Heinz’.

However, even here, Wikipedia admits that it it is used originally only as a marking to indicate ownership or entitlement over a thing (including living ‘things’) considered as one’s product.

The practice of branding – in the original literal sense of marking by burning – is thought to have begun with the ancient Egyptians, who are known to have engaged in livestock branding as early as 2,700 BCE. Branding was used to differentiate one person’s cattle from another’s by means of a distinctive symbol burned into the animal’s skin with a hot branding iron. If a person stole any of the cattle, anyone else who saw the symbol could deduce the actual owner. The term has been extended to mean a strategic personality for a product or company, so that “brand” now suggests the values and promises that a consumer may perceive and buy into.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brand

It is worth noticing how the usage relating to the branding of humans is omitted here, where the issue (as with cattle too since they stray their owner’s boundaries and fail to acknowledge the boundaries and fences that mark ownership claims) is not only the theft of product by competitors but the product’s own unconscious or conscious failure to submit to being thus owned and made into a commodity. Human slaves, Southern American owners acknowledged by the use of brands the fact that some slaves even chose to flee their enslavement. Some of the entitled white apologists of slavery were also apparently amazed to discover this fact: one of the most appalling examples of ‘scientific racism’ of the nineteenth and twentieth century was that of American doctor (Samuel A, Cartwright), who invented the disease category drapetomania to explain this errant behaviour.

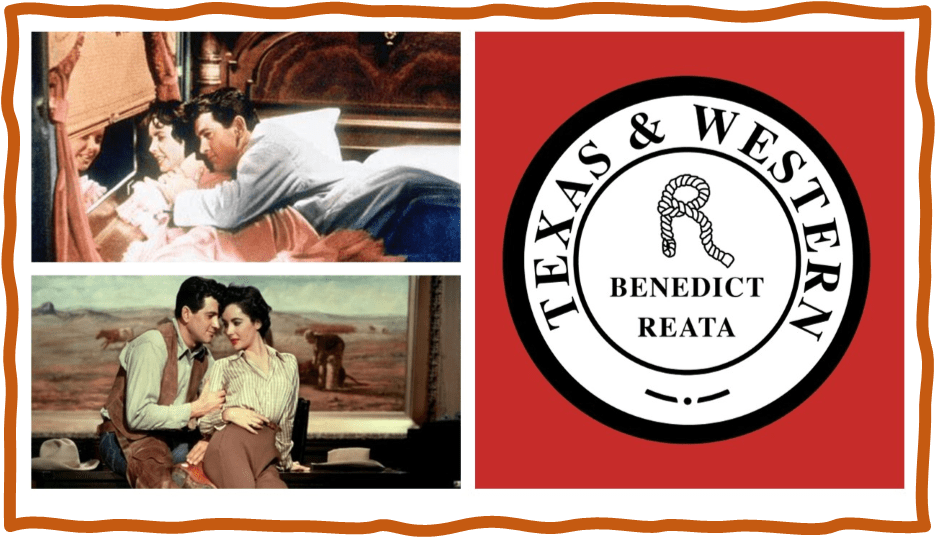

Interestingly enough, the link between commodity creation and symbols of ownership, even starting from the branding of cattle, is the subject of the film Giant (see what I say about this in a blog on Rock Hudson at the link here). The ‘Benedict Reata’ brand (reata is a Mexican term for a lasso hence the way the R of the brand is formed and its association with the capture and training of runaway or otherwise ‘wild’ animals) and it is both stamped on Jordan Benedict’s cattle in a scene in the film and printed on the ranch’s portal, as it has been throughout the history of the Benedict capture of the ranch bought from impoverished Mexicans through deals that were clearly exploitative, as James Dean’s character, Jett, tells Rachel (Elizabeth Taylor). Later in the film, when the Benedict wealth is now from oil, like that of upstart Jett, the brand appears on all kinds of things, including a jet plane. The only thing that cannot use it or its associations, by a legal process described in the film, is Jett’s new oil firm based on a gusher found on his little piece of land inherited by Jett from Jordan Benedict’s butch sister, who was sweet on Jett, which must transform into JETTEXAS.

In the pictures of Rachel’s entry into the Benedict Reata brand by train and being beguiled in situ, we see too that women too often felt, or ought to have, in the twentieth century and beyond that the loss of their father’s name to the gain of another man’s name (here Benedict) was also a kind of product re-branding. In the honeymoon suite the couple are looking out of the train window at the dry ranges of the Benedict Reata holdings, whilst in the range, she succumbs to Jordan (Rock Hudson of course) in front of a large landscape painting of the ranch in which, just to the viewer’s left of Elizabeth Taylor, you can see a cow lying in the ranch’s dirt and held forcibly in order to be branded with the Benedict Reata lasso R logo.

Of course words change their meanings (and I favour this fluidity in language) but the word ‘brand’ will always feel as stigmatised for me as is one of the means of branding – for bearing a stigma is to carry a mark of one’s meaning in someone else’s interpretation of you far too often, whether those stigmata be in the body of Christ (or earned by the loving desire of his priests such as Saint Francis) or the unseen label carried by survivors of the mental health system or other bearers of a social stigma.

My feeling about modern commodification, especially those of celebrity, is that the meanings I take from the phenomenon resemble those in the Campi painting of Saint Francis in the collage above, a desire to be marked out for easy identification in public knowledge. However, unlike Saint Francis who preferred seclusion and recognition by the animals to human beings, being burdened by a celebrity whose mark is ambivalent ensures that its bearers complain of its downsides as well as profit from its upside.

And, of course, they may not profit, for the branding of a star is often to the benefit mainly of an entrepreneurial manger and person-brand inventor, as was the case of Rock Hudson with his agent, Henry Willson, or Elvis Presley with Tom Parker – an issue made much of in the recent brilliant Elvis biopic, and described thus by Mark Kermode in The Guardian (see the quotation beneath the collage).

“Without me there would be no Elvis Presley,” drawls Tom Hanks’s Colonel Tom Parker (aka Dutchman Andreas Cornelis van Kuijk), a “snowman” or carnival huckster who does his deals on a Ferris wheel and who sounds genuinely amazed that “there are some who make me out to be the villain of this story!” Most will share that view as the curtain comes down on this whirlwind chronicle of a career from which Parker took 50% of the profits and 100% of the control.

https://www.theguardian.com/film/2022/jun/26/elvis-review-blistering-turbocharged-chronicle-of-the-king

If finding association with brands did not mean giving up some part of one’s chosen identity, all of it in the case of cult adherents like Saint Francis, I might buy into it consciously here as I no doubt already do it unconsciously when I feel I can only purchase certain versions of a product, wherein there seems no difference in type or quality – although some claim there is for Heinz Beans. I have known people use affiliation with even one particular artist as a brand of what they see as some other quality such as ‘genius’: here I am thinking of Prince. But Prince made an art of changing his brand and even playing with that very idea of what branding means – in his choice, for instance, to be know as The Artist Formerly Known as Prince (for a blog on what Prince means to various people see this link).

Moreover, as the collage (using my earlier blog) above shows, many artists use logos representing their performance, though they oft vary conventional icons in line with crossing boundaries in describing their own experience as artists or persons. Prince’s particularity was to sell a kind of queer boundary-crossing that could not be labelled medically – as gay, straight or even bisexual – because it was just being absorbed into the potentialities of sexual love uncoupled from reproduction, even though examples of his sexual behaviour seem always to be solely with females. The answer from Prince (and perhaps Dickens if Nick Hornby is correct about the similarity of both artists) is that one must brand multiply and with the chance of instant and continuing metamorphosis of brand. This is not because one is disloyal but because one is guided by an abstract notion of freedom. The label ‘best friend’, for instance, I used in that blog has, for instance, turned out to be a false branding for the person I thus branded has, he has now declared himself, to have ‘ended our friendship’ in the interests of his freedom.

I am not sure I believe in that notion of freedom (in its modern and philosophical determinations) of course. Even existentialists bind themselves by knowing they must choose sometimes between alternative commitments as Sartre explored in Existentialism Is A Humanism (and Jean Genet and Albert Camus in every novel they had ever written). However, it is likely that no-one will ever relish the feeling of being owned by anyone. I once cried to hear Dusty Springfield’s You Don’t Own Me, for reasons I set out in one my Edinburgh blogs from this year’s holiday. And some feel the threat of being owned even where it is not claimed. Others though fail to feel it, as in the case of victims of domestic abuse, where sometimes victims feel the desire to be owned and feel it more strongly than any desire to make a free choice.

But branding is implicated here too for ownership. As I wrote this I had to go upstairs and observed from our bathroom window that the local farmer had put his sheep in the field behind our garden. Sheep are silly creatures by stereotype and do not think of themselves as owned in the interests of a farmer’s profit margins nor as enslaved to the human lust to eat meat, although they ARE. They can be branded then by use of a simple dye (as in the photograph above taken from our bathroom window) that more knowing creatures might wash from themselves or even unknowingly rub against the fence that attempts to contain them, hence the needed for a deeper marking burned in or a skin slashing branding implement. Southern slaveowners used a whip for this purpose sometimes.

Branding in slavery was very real, painful and relatively recent in history. It survives even now in more metaphorical forms largely but often as painful, for it to be necessary to have a Black Lives Matter movement still, however ‘branded’ by the right and the self-justifying and entitled as ‘woke’. That tendency in history has always reserved to itself the right to brand the marginalised in its own accounts of the global story and to ensure that branding retains its association to punishment as well as ownership and the policing of the protections of its entitlement to use everything in its own interests. And though, we might prefer NOT to look, the tools slave-owners devised to ensure the brand sunk deep into the souls of the slaves they owned sear our vision and should do so.

We cannot free ourselves now of a branded world but we can decide that we never identify with any logo or label that attempts to belittle us. Moreover, since to choose brands may be inevitable if we are not to miss out on the good in the world, let’s ensure the associations of that brand are ones we, in part at least, invent or re-invent for it and reflect our own creativit. This is what, in his own way, Andy Warhol did for all kinds of brand, including the brand we call gender.

But some brands can only be opposed by an insistence that, in its main examples, black, brown and olive lives, are never defined by anyone but the livers of those lives branded Black and in their own way. For some that embraces the political term Black. Every other alternative to that position is an expression of mere entitlement by the hegemonic forces in a society – White, rich, socially empowered by prescription, male, heteronormative and so on.

With love

Steve