What things give you energy?

Philosophers tell us that Aristotle used the term ἐνέργεια (it transliterates as ‘energeia’ – the possible root of the work ‘energy’) in a very different way to the use of the word in modern science, whether that be in physics, chemistry or biology, where it names various kinds of measurable energy types. Aristotle used the word, Joe Sachs thinks (as reported in Wikipedia – the section is below), to name the quality of what we need to translate as the ‘being-at-workness’ of a thing, its potential as action towards a goal that manifests what the thing is, such as some kind of state of being or of making or forming itself into what it is in essence. Clearly, the two meanings can neither be helpfully compared or discussed in relation to each other.

From: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potentiality_and_actuality

What we can do though is use the difference in meaning to convert this question from one about things that we take into ourselves to a question about the quality of our self-realisation, our worth to not only ourselves at best but also to others. I suspect the question-setter here assumes we will think about ‘things’ that make us feel energetic, as if we contained, for as long as the source lasts in its effect on us, the power to do something we want or have to do, such as play a game, or go to work or fight a war (though hopefully not the last). An expected list of answers might include:

- things we take into our body that contain measurable amounts of energy within themselves that the body converts to use in sustaining action of some kind (such as the calories in foodstuffs);

- things we take into our body that act as catalysts to the body to use energy supplies of its own, stored within itself (as some drugs such as caffeine do – usually mediated by internal chemicals (notably dopamine) when stimulated by an external drug);

- or, doing something physically or in imagination that, despite the measurable energy cost to our own body that it might involve, makes us think, feel and /or sense energy as if we had gained the equivalent of such measurable energy in input.[1]

- [1] Although the first two explanations rely on external factors (exogenous factors in the jargon) that are applied to the body, I don’t, of course, in point 3 deny that the psychological effects described as feelings might be the result of triggered internal biochemical activity (endogenous factors in the jargon). I have not, nor do I need to give up on the importance of levels of explanations that re-invoke the material when apparently talking about mind or spirit.

However, invoking Aristotle’s admittedly refined word coinage to name things badly named, in his view, by previous teaching philosophers and thinkers, has a point for energeia is not a thing in itself but a quality of a thing, a description of what it is as, in essence, what it does or has the potential to do. In that sense, I think we talk about not a transfer of material quantities or even their psychological or spiritual equivalent or representation but of purpose and potential for good or ill.

And, if we do this, I think it is hard to continue to talk from an egocentric view alone when answering this question. I do not take or get given (willingly or not on the part of any possible donor) an amount of measurable energy but partake in it collaboratively so that giver and taker both benefit, perhaps in increasing circles of influence. And, in these terms, energy is that which makes humans be and act as humans and fulfill their generic purpose. I say ‘generic purpose’ because it is inconceivable to me that the fate of individuals matters that much in the bigger picture (in this I think I am with the arguments of the philosopher Donald Parfitt’s great book On What Matters) beyond their contribution to a mass of sometimes contradictory but fruitful other contributions.

The ‘generic purpose’ is to survive as a generic species because individual humans are not prone to immortality but as a species they might be perhaps. Of course, even here we have to say ‘perhaps’, because in times humans are too often concerned with the self-interest mainly of a Few (certainly a minority – their model might be Donald Trump) to keep manifesting their conscious or unconscious propensity to destroy the ecosystems on which we all, the Many and the Few, depend for that generic species survival.

The question then turns into what makes the quality of energy in the world matter? It turns back on itself as a question such that the quality of what we take from the world, or leave to fulfill its own purpose (its energeia) matters. Moreover, if we take from the world its qualitative ‘good’ to feed ourselves, should we take it (or receive it as a gift or sacrifice – ritual might matter when shared inter-species interests of life and death are involved) only for a good purpose.

That is, having taken or accepted this qualitative good, how do we manifest it – act to realise the quality of humanity to which it contributes. And we need this shift in our thinking, even if we remain entirely materialistic in our analysis. That is because if we think the effects of the beauty and goodness that we sense in things we used to label products of the mind and spirit alone (art for instance) matter, it is because they generate material effects on us as a species. I would name those effects as being collective actions: production and the clearing away of the waste implied by human production, even the death caused by it as Ruskin insisted on in Unto This Last, fair distribution and collection of returned benefit that is not needed in one place or space for use in another place or space.

We do not need to return to a form of Christian Socialism to do this (though even I as an atheist see virtue in the idea) but we do need to use past wisdom (whether from a pagan source like Aristotle or the accumulated wisdom of the Bible in progressive traditions that were born with Christianity) to inform our response to present needs.

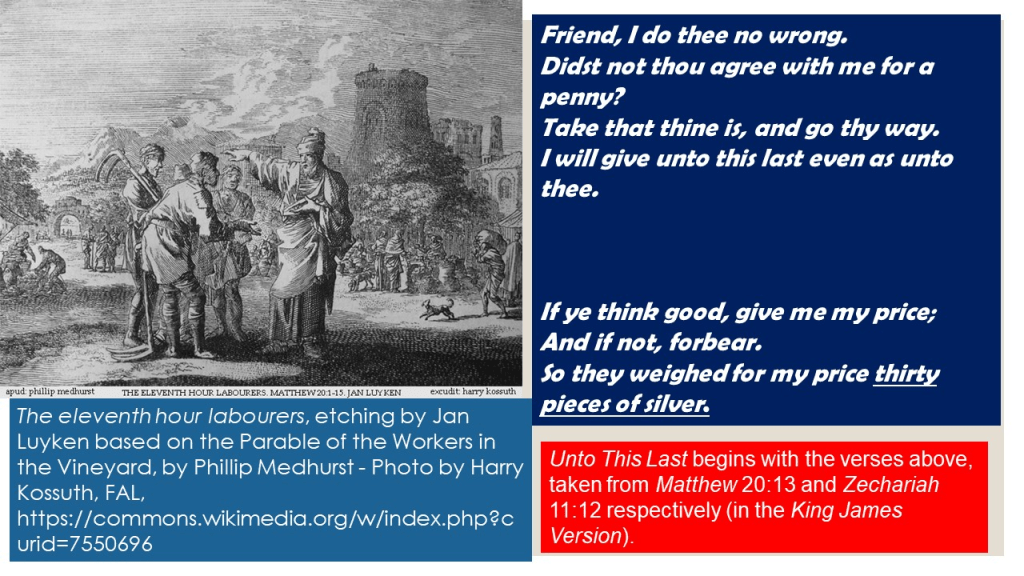

So I think that we need to think carefully in our answer when we think about things we take or accept from others or which we allow to be taken or freely give (even sacrifice) to others. The price of Christ’s life being set by Judas and the oppressive forces that colonised the world at the time was thirty pieces of silver. Although the currency and amount we use to trade the meaning of human life as itself the source of beauty, good and all other value has changed (thirty pieces of silver would not buy Donald Trump’s, or Rish Sunak’s, breakfast napkin) , when we act selfishly in an politico-economic system (global capitalism) that believes self-interest (the same selfishness to wit) is the best driver of its operation and action, we act in a manner that is as near the meaning of evil I can think of. Let those things as they are exchanged (or the representations of their meanings in the stock exchanges of the world) keep reminding us that they are bought and sold to the loss or gain of the life and death of our species and planet.

Love

Steve