Share a lesson you wish you had learned earlier in life.

It is almost certain that Socrates never said, as people sometimes believe, anything like, ‘All I know is that I know nothing’, but then can we we truly ever be certain about anything. How people came to believe he said this is explained in many places. But let’s take Wikipedia for it is so accessible to everyone. There the most relevant entry on the issue says:.

in the Apology, Plato relates that Socrates accounts for his seeming wiser than any other person because he does not imagine that he knows what he does not know.[9]

… ἔοικα γοῦν τούτου γε σμικρῷ τινι αὐτῷ τούτῳ σοφώτερος εἶναι, ὅτι ἃ μὴ οἶδα οὐδὲ οἴομαι εἰδέναι.

… I seem, then, in just this little thing to be wiser than this man at any rate, that what I do not know I do not think I know either. [from the Henry Cary literal translation of 1897]A more commonly used translation puts it, “although I do not suppose that either of us knows anything really beautiful and good, I am better off than he is – for he knows nothing, and thinks he knows. I neither know nor think I know” [from the Benjamin Jowett translation]. Regardless, the context in which this passage occurs is the same, independently of any specific translation. That is, Socrates having gone to a “wise” man, and having discussed with him, withdraws and thinks the above to himself. Socrates, since he denied any kind of knowledge, then tried to find someone wiser than himself among politicians, poets, and craftsmen. It appeared that politicians claimed wisdom without knowledge; poets could touch people with their words, but did not know their meaning; and craftsmen could claim knowledge only in specific and narrow fields. The interpretation of the Oracle’s answer might be Socrates’ awareness of his own ignorance.[10]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_know_that_I_know_nothing

Photograph of a bust of Socrates in Western Australia by Greg O’Beirne. Cropped by User:Tomisti – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=808060

So let’s stick with the Jowett translation where Socrates compares himself to those that profess wisdom, for such a person knows nothing, and thinks they know, whilst “I neither know nor think I know”. A point like that though, let’s face it, can never be an absolute statement of truth about oneself but only a comparative and relative one. It is not wise to claim to know nothing because that might mean there was no purpose to past learning and that there will be none, in extension, in future learning.

However, it MAY be wise to understand that on no subject do we ever know all there is to know, nor even all that it is either desirable or essential to know, if we discount the value of learning more from others. Socratic dialogue assumes that anything we think we know may be an illusion of knowledge until it is examined and tested in dialogue, or, as ‘the science’, in Greta Thunberg’s phrase, might add tested against evidence.

I have to say that though I am happy to say I wish ‘I had learned’ that ‘earlier in life’, it might still be an illusion that I have learned it yet – and time for learning surely diminishes, now I see my 69th birthday on the horizon. Having learned absolutely, in fact, is always an illusion for the point is that knowledge is the summation of what there is to know about anything is not only never achieved but never achievable, or only approximately so. The danger is in the thinking that you know, sometimes in thinking that that though you do not know everything, you know ‘enough’. For in all cases mentioned, to believe that, in effect, denies that learning more would be beneficial always and is often a necessity foregone.

It denies too that knowing is only something diversity of perspective and experience of the object to be known can ever achieve, even optimally. And all the factors involved in knowing – the people who need to know and the thing necessary to be known at the very least but perhaps too the framework in which we understand how things are and continue to be (their ontology) and how they can be known (their epistemological prerequisites)– change in time as a result of the flow of circumstances in which the thing to be known has salience.

Yet we think we know all kinds of things we do not know – about the nature of loving and caring, about ourselves and others and the network of relationships that sustain us. Do we even know enough about the relationships between the things necessary to sustain us in our global adventure as a species, or group of species (for who knows how we relate to other life forms – a thing viruses often try to teach us). Even, for instance, the lessons of CORONAVIRUS – that there are networks in the things we call LIFE that connect us across supposed boundaries, geopolitical and socio-biological, which not only do we not know but do not know how to sustain respect for, or an open mind about. Instead we have used the lessons to bolster things we think we knew already – the supposed importance of containment and suspicion of boundary-crossing in ways we think we can control, though it seems we cannot even do that.

As climate-environment interactions change what phenomena we need to know will change (are already changing). Issues like geopolitical migration will increase in their visibility, defending national boundaries will become more frequent together with surveillance and action against the threats to established privileges and to privileges whose source we do not yet know. They will include factors of geographical location, for instance, as the factors that favour certain regions change with the flow of geothermal activity of which we have as yet no model. And political parties pretend they have the answers to this within present paradigms – like the necessity of continued economic growth and boundary defence as held as if they were absolutely known things by both of the arrogant parties that rule over us badly now and want to do in the future.

It is not good, people think, to admit that what we know is limited and always will be, although we optimise it and we need to continue to do so as the meaning of the Heraclitus motto, as cited by Plato, δὶς ἐς τὸν αὐτὸν ποταμὸν οὐκ ἂν ἐμβαίης (that ‘we never step in the same river twice’) becomes self evident and we know the flow of being and how we must learn to know about it. But it is a necessity. And it is personal too, for what a person is or is thought to be can no longer be something we KNOW.

We don’t know enough, and the chances of thinking that we know it will diminish rapidly as politics and even relationships between people change with the accidental scarcities and accidental redistributions that new (because not before known) global realities of climate change, species and political boundary crossing factors emerge. I used to think I knew about my position on basic questions of human ethics and politics but I despair of the rank arrogance of all positions available now that contest each other hopelessly on social media, for that is the place where people who think they KNOW THINGS, even EVERYTHING, seem to be congregating; congratulating each other on the rigidity of their opinions and the absence of any link between those and how they live. I have been one of those – no doubt am a bit still – and seem so, more often.

But the point is we need to return to an awareness that human knowledge is a kind of vanity. We must do this not because we compare ourselves to a GOD that knows (or GODS that know) ALL unlike us but because we are aware (we are woke enough let’s say proudly) that until we learn from the world and each other, and especially from those we silence with not only oppression but poverty, our joint need to KNOW more.

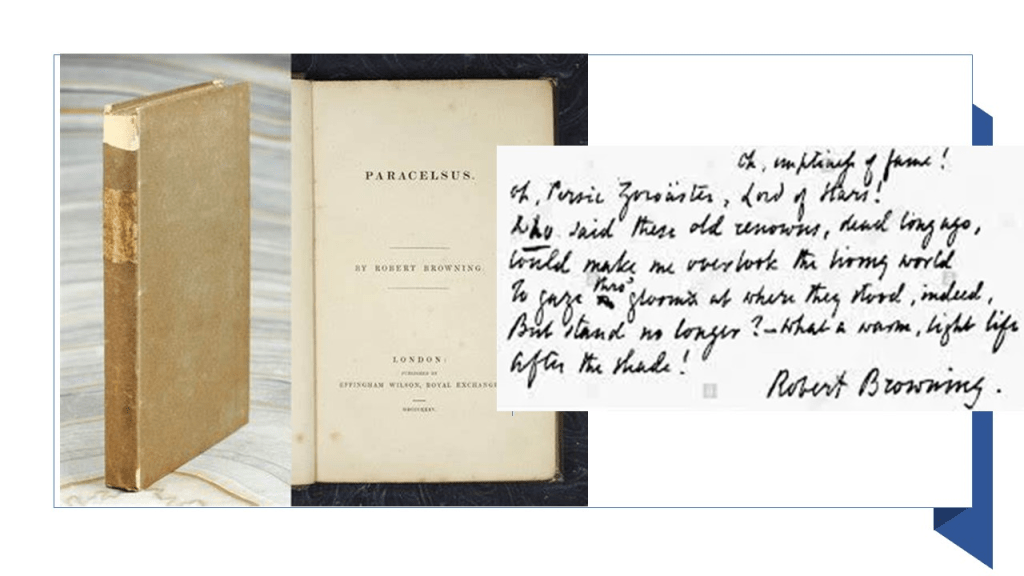

As I wrote that I thought of Robert Browning publishing his long dramatic poem Paracelsus (now hopelessly forgotten and dustily untaught in the academies of knowledge) in 1835, intent from his study of Shelley and sure that old knowledge that excluded that former poet’s political radicalism and commitment to the ‘Many’ not the ‘Few’ (see The Mask of Anarchy) would fail him and wrote much as I did above, though of a young and yet untested man of the futility of past and institutionalised knowledge:

Their light! the sum of all is briefly this:

They labored, and grew famous; and the fruits

Are best seen in a dark and groaning earth,

Given over to a blind and endless strife

With evils, which of all your Gods abates.’

No; I reject and spurn them utterly.

And all they teach.

For FULL TEXT, see: https://archive.org/stream/paracelsusofrobe00brow/paracelsusofrobe00brow_djvu.txt

In the end of Browning’s poem, the character Paracelsus who says that as a youth becomes a little less radical, a little more accepting of the fruits of the aged ‘knowers’, and realises that loving trumps rejecting and spurning. However, he still claims that to know without meaning to share that act of knowing in the interests of those marginalised by our present state of ignorance is not knowing at all, and that learning must proceed after his death in all. He dies imaginging the Shelley figure in the dramatic poem (Aprile) having his hand in his and comforting him that death is a minor change in the light of the development of universal love and the knowledge it continually aspires to.

I remember reading Paracelsus by lamplight in darkened chambers in Cambridge, where I thought I was learning and believed in becoming an expert if but in the poetry of Robert Browning. I know better now and though it is not true that ‘I know nothing’, it is true that ‘I know that I do not know enough’ about anything that matters. I can only hope others will feel the same and the dark trajectory of the world into ‘inhospitable waste’ that is continually imagined even in Paracelsus in 1835. That ‘waste’ comprehends the onslaught of the Industrial Revolution, and mass urban poverty, and the failed hopes of the Great Reform Act of 1832 (no further forward than Shelley reflecting on the Peterloo Massacre in Manchester in 1819). Wasted hope will not not be the only thing we as a globe will truly ever know hopefully: ‘a dark and groaning earth, / Given over to a blind and endless strife’ not our only human achievement.

Love

Steve