In 2018 Lewis Segal wrote in The Los Angeles Times of Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake, playing there at the time and praised in particular ‘the members of the swan corps: feathered, bare-chested virtuosos whose sense of menace kept the work from collapsing into short-lived camp. Bourne created the work at a time when a law against promoting homosexuality still existed in England. It’s gone now, but you can see how the swans destroying one of their own — and his male, human lover — speaks to the homophobic violence that still exists almost everywhere’.[1] The explanation of Section 28 may be lacking, as indeed is the long arm of its effect and the threat of its resurgence in the UK (but that was 2018). The point is that whatever its dated elements in how thought about queer and other experience is represented (refrigerator mothers and dumb blondes for instance), it is a work that STILL demands attention from everyone in our community. This is my impression on seeing the revived screening on 13th September at the Gala Cinema, Durham City, UK.

When I was a true ballet virgin I wrote a blog about seeing the Birmingham Royal Ballet’s production of Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake (see it at this link). Nothing in that blog about my reservations regarding the hierarchical nature of ballet applies in the same way to this production, even though it too clearly distinguishes the corps de ballet from principals and soloists. There feels to be much more mix in the configuration of casting for the whole production – between and within acts and scenes. Moreover, Matthew’s Bourne’s version has very many scenes, especially in the equivalent of Act 1 of which traditional ballet could never conceive. The whole feel is of a whole work of art and a social body that works collaboratively in the production. So much is this so that I could not express my admiration for the ‘swan corps’ in quite the same way as Segal, for what comes across in the very scene he refers to – the murder of the White Swan and the Prince after they have been in bed together as lovers is about tightly regulated teamwork across the corps de ballet and principals. It doesn’t quite work in the way it did for the Birmingham Royal Ballet. This is perhaps too because a filmed production picks out individuals in the corps sometimes as much as it does principals, who are defined solely as individuals. Moreover in the theatre, Sadler’s Wells has a kind of space that can be made to look small – no doubt why it is not so useful for the traditional form of this art nor grand opera. That point about homophobic murder requires such teamwork to convey as powerfully as it is conveyed.

The same point can be made though about Bourne’s Swan Lake (more so even) despite the greater theatricality and narrative focus of this production about its nature as a temporal sculpture. Bodies (individual and social ones) are sculpted in the stage space – although the dynamism of the metamorphoses of shape is achieved at what feels, at least, to be a much more rapid pace, especially in Act 2, now set in a public park rather than the park of an aristocratic hunting lodge.

Although there is a more ritual pace of motion in Act 4 that is slower than Act 3 and is set in the prince’s private bedroom, where he has been locked by his mother in fear of the effects of what she sees as a ‘nervous breakdown’. It is a breakdown associated to the complications in his sexuality. For his sexual feelings are directed at her, his mother, and a male lover. The latter is now a sexy black-leather-clad stranger appearing in Act 3 who he may have imagined and for whose attentions he competes with his mother. She has a kind of Catherine the Great type of hunger for young male flesh, even from Act 1, wherein she selects young men from among her guards. In such a different kind of narrative to traditional version of Swan Lake, imagine how differently body sculpting on stage works – whether social or individual. This is what I said in the earlier blog, explaining my virgin response to something new to me:

here, I thought, was an artform I could see as an extension of other things I love – a form that turned figure sculpture into something living in time, made dynamic by story. Ballet is obviously about the body, I suppose; not just the individual body, though that makes incredibly complex forms, but the whole body of the ballet company – hence rightly known as corps de ballet – a social body which moves in three-dimensional highly sculpted motion. In Swan Lake the corps de ballet is a star in its own right, notably of course, but not only, in the role of the whole body of swans in Act II, but especially in Act IV, where words fail to describe the effects, but which start with the whole avian social body rising through the dry ice enacting lake-level mist at its start.

We need to start with the fact that the Bourne Swan Lake is not just adapted, it is reshaped although less in the sequences of the choreographic units (though the competing national dance troupes in Act 3 ‘selling’ their own royal princess as putative bride to the unmarried Prince, always de rigueur in the classical form, have no such function in this version). The Act 3 dancing becomes instead a means of showing how the direct and rather openly coarse sexuality of the black-clad Stranger (the substitute for Odile’s Black Swan) throws into chaos the organised ritual of courtly dance routine, making its whole social body movements ever so much RAWER and more VISCERAL.

I blogged in anticipation of going to see this production too and therein asked myself some questions that no longer seem so relevant having seen the screened production but you can see that blog at this link. However, I think it would be fair to expect at least a reflection on my final question there, which was anyway in danger of being rhetorical and too easily answered glibly in terms of Bourne importing modernity of queer meaning into a ballet, where indeed it may exist at a subtextual level but not on the surface of the plot. The question was:

I wonder what Tchaikovsky would have thought; whether he felt that the gap between his own sexual being, as he knew it, and the content of traditional art forms could ever be bridged, let alone closed?

Queer and gay identifying males who see Matthew Bourne’s version WILL without a doubt find it relevant to them as people living in a still divided society where we are still marginalised if not now written into law as criminals. The themes of basic divisions in our thought processes with regard to our sexual, social, private and public lives, the naked presence of aggression at the micro level, in the form of censoring and eradicating even thoughts let alone expressions of desire, public and private violence arising from heteronormative group processes and, finally, the presence of suicide as an option for young men divided and oppressed thus is still with us as a community. There is a kind of Hamlet-like ambiguity in the traditional ‘script’ of the ballet but the queer content largely has to be inferred (in both works of art in fact with regard to the Prince who is their focus). But what is clear is that though the traditional versions allow us, in the same way, to bathe in Tchaikovsky’s score; the tensions in that music are really only given adequate meaning (an objective correlative if you like) in Matthew Bourne’s version. I think this will apply too to people who do not identify as queer or gay who see it.

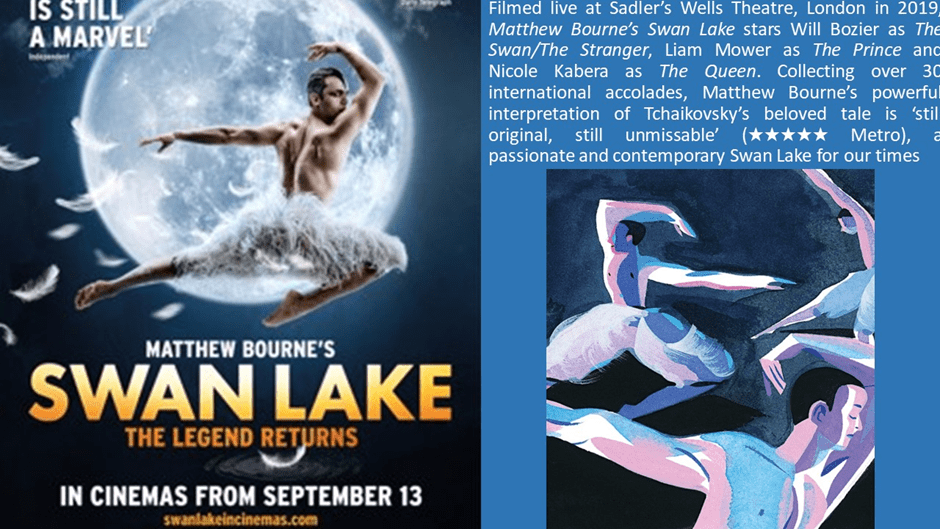

However time presses and, in order to blog on this experience, the only method I could imagine was to walk through my memories of the sequence of the story, which can be found in the Wikipedia entry at this link (It tells the new story at great length). I will use collages of already published pictures from the Internet. Of course these do not always feature the same cast (and that is largely true of the Swan / Stranger dancer, who appears to be Matthew Ball from the 2018 production not Will Bozier) though amongst other principals the Prince and the Queen are danced by the same people, Liam Mower and Nicole Kabera).

The pictures I found are not, of course, meant to represent the whole story and I use them really to demonstrate the thoughts I had watching the film and reflecting on it afterwards. So I do recommend the Wikipedia re-telling to get the story straight (findable at the link in the last paragraph). Moreover it is worth reminding ourselves that Bourne conceived of his piece in darker times for our community by citing what was said in The Observer review of a production five years ago which reminds us that it was first played 23 years even before that production. I do it because we need to remember the context in which we watch it, although not (as newspaper reviewers are wont to do) become too complacent that, even if things might have improved in queer lives, that those improvements are stable and not under threat.

The current production (2019) features dancers who were not born when the original was launched 23 years ago, and it’s easy to forget what a risk Bourne was taking in his homoerotic framing of the story. The 90s was a less tolerant era than our own (one newspaper captioned a picture of Bourne’s male swans with the words “Bum me up, Scotty”), and if the ballet’s dramatic momentum had faltered it would have sunk, probably taking Bourne’s career with it. But strong storytelling and a charged emotional core ensured that Swan Lake flew, and continues to fly.[2]

The story, though utilising the sequence of Acts of the original, is not the ssme. Act 1 changes scene frequently, in the middle section actually mounting a spoof ballet in front of the Queen and her son, the Prince, largely in order to poke fun at the gaucheness, stupidity and class commonness of the ‘Girlfriend’ who appeals to the Prince largely because she is not a staid and dull aristocrat. However, the idea of manifesting a dancer-character’s ‘spots of commonness’ by showing that she does not know how to behave properly in traditional ballet performances, is making its own point. Traditional ballet is not only heteronormative but it is so in an exclusive hackneyed form.

However that scene also shows the tendency to preference comedy (even to the point of stereotypes common to such like the ‘dumb blonde’ lower class ‘Girlfriend’) in this production. It uses stock circumstances, like the relationship between the upstairs and downstairs roles of the servants who get the Prince out of bed (some of the corps acting as steps to allow him to step down from a very highly raked bed to the floor of his bedroom in stark iconic recall of the upstairs – downstairs theme). This then is dancing that yields to using body-shaping functionally to tell a story much more than does traditional ballet (where such functions are given – as in Coppélia to buffa characters, often non-dancing ones like Dr. Coppélius).

Once out of bed, as in the collage the corps de ballet are distributed at the extremities of the body (another kind of corps) of the Prince (picture on viewer’s left), washing and changing him from night to day status. It is pure fun but must make for disciplined dance routines. After that, the gradual transition of the bedroom to a state room (the bedhead revolves to become the red state viewing balcony at which the Royal Family stand) is itself made part of a ‘sculpting’ and decoration of the stage as the cast pull ropes that appear to bring the state wall decorations – those red banner-like drop curtains, into visibility, falling as they do from above the stage. See the picture bottom right I the collage below.

The whole act is about the artifice of royalty and its insignia, a point that presumably drives the Prince into the pursuit of authenticity in his relationships. Of course he won’t find it with the low-class girlfriend. He will find it with the Swan, a lover he may just be imagining, and the Swan’s counterpart in Act 3, the male Stranger in black leather. Other scenes emphasise the shadowy relationship between the prince and his mother. Top right is a scene played in front of an empty frame for a dressing mirror before which a dance shows the Prince longing for proximity with his mother, a proximity she denies; the scene lit from below so that huge shadows of those actors are cast on the back of he proscenium, creating an almost supernatural replication of an awesome family romance involving desire and denial of all kinds. In a sense, these dark shadowed moments are our way into the evening and night scenes to follow where motivation of and by desire is prominent, even to the point of probable illusionary vision.

Following the above is the scene of the Royal Family from their onstage box watching the ballet before the scene shifts to what is labelled onscreen to be a club in Soho. Bar Swank, which becomes bar Swan at the end of the sequence, even using the motif and logo of a Swan Vesta match packet projected onto the wall exterior to the club to emphasise the transitional liminality of the shift from club to a potentially symbolic park:

In Bar Swank, the Prince discovers the Girlfriend dancing with anyone who will have her, and together with his equerry he pays her off. The scene again is played for fun, until the Prince is left outside the club and wanders off alone to the setting for Act 2, a public park. The dancing in Bar Swank is mixed and various, replicating disco dancing motif and patterns, though in a finely honed manner.

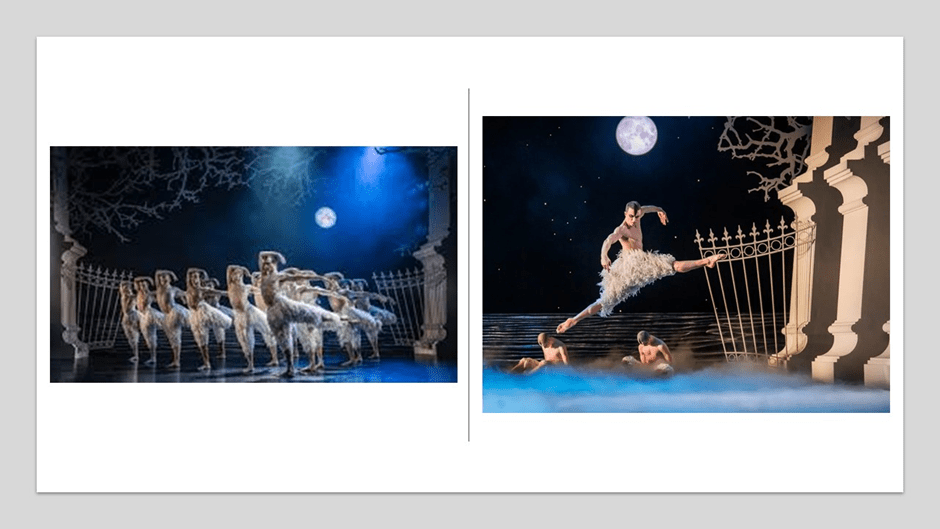

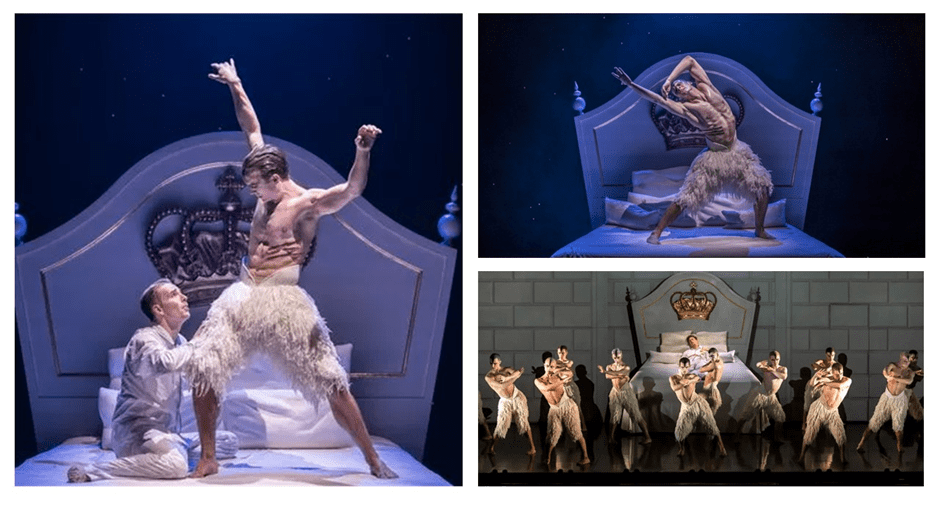

The public park is where the Prince dances alone before writing a suicide note that he attaches to a ‘DO NOT FEED THE SWANS’ sign. It is then that the swan enters together, eventually, with the swan corp. Much of the dance movement mimics the bird’s motion. The fine drawing in my first collage (from The New Yorker) shows well how arm extensions, common enough in ballet movement, often mime the straight line in which a swan’s neck is held in flight. Below, the Swan caught in mid -air suspended over the notional representation of the ripples of the lake that contains below him and it members of the swan corps. The Swan at this time is a clear leader of a flock. See how in this still his arms suggest wings and the curvature of his legs under a feathery set of pantaloons suggest the rounded body shape of the bird in flight, the combination of ungainliness of shape and the precision achieved in flight is the wonder involved in seeing this animal.

At other times, leg extensions mime these straight lines in flight – not as representations of a swan per se but suggestively. In Act 2, the Swan is supremely confident of his role as the alpha bird of flock, venerated by the corps, who sculpt the space in which they dance with exquisite ordered patterns, as in the conventional productions (like that of Birmingham Ballet in my first blog). These ordered patterns will disappear in Act 4, when the swan corps turn against their leader for queering the boundary between bird and men, and perhaps too the boundary that they feel should exist between male and male as sexually romantic lovers whatever their species. See the picture to the left in the collage below for the patterns, though the aerial pre-eminence of the Swan over the swan corps is more the issue on the picture on the right. Whilst the swan corps when he is there, hide in ground mist, he soars into the represented moonlight.

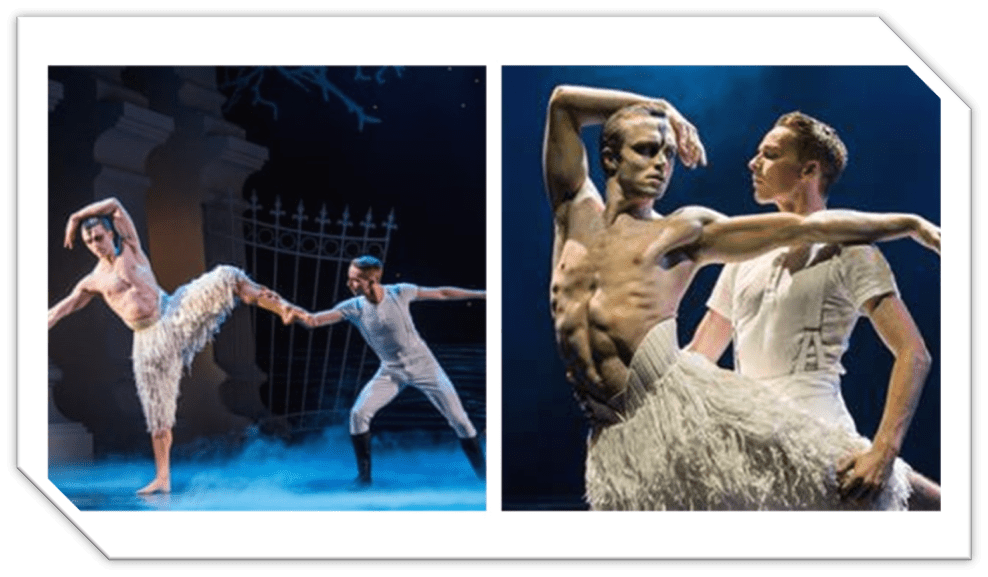

It is in this context that the fragmented pieces of the pas de deux of Swan and Prince are enacted, when those partners fill the stage with their romantic embodied coupling. That these scenes are imaginary fulfilments in the Prince’s mind is always possible of course, hence the ambiguity and duplicity of mist in the mise en scene. The beauty though of the sculpting of the pair astounds both when it is more conventionally that of a ballet pas de deux (on the right) and when it definitely plays with strange shapings and body connections (on the left).

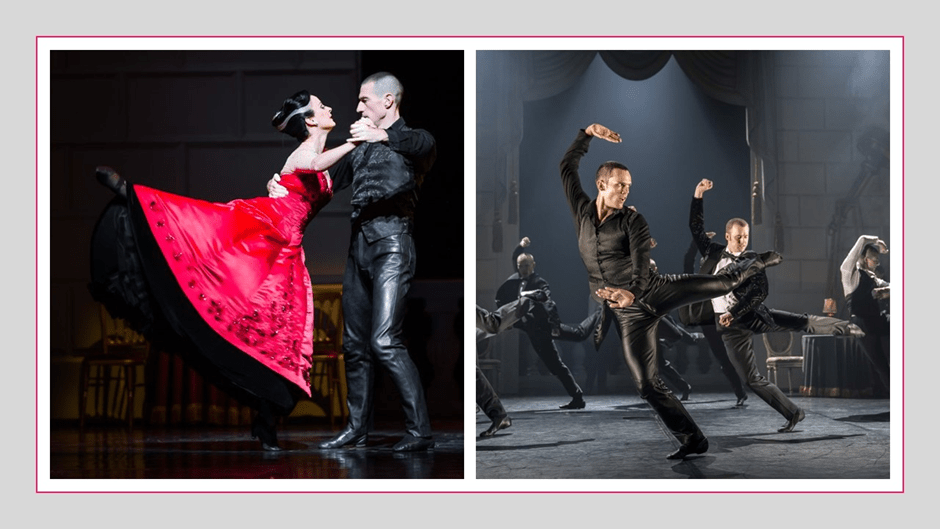

Act 3 is so much more difficult to capture. I need to see it again. The stranger in black leather is clearly an alter-ego of the Swan and danced by the same man just as the same ballerina dances Odette and Odile / the White and Black Swan in the conventional productions). What the Stranger introduces into this court-scene is the kind of disruptive force of a new class of man coming into a staid society – a kind of Heathcliff. He enters by mounting the balustrade rather than entering left and right at the window as other characters do throughout. In some sense he is a fantasy – but whose fantasy is he? Is it the Queen’s lust for a lover even more marginal to her circle than the subaltern guards she otherwise marshals to her bed earlier, or is it the Princes fantasy about his mother’s forbidden sexual being (forbidden anyway to a boy child when the object of his desire is his mother (whether he knows it or not)? The latter possibility is also the theme more directly in Oedipus and less so in Hamlet in Freud’s reading. The Stranger’s sexuality is fluid. He dances viscerally with men (on the right below) or women – individually or in social corps. He dances sexually with the Prince only to disappear leaving the Prince clutching himself as if he sees to his despair and breakdown the Stranger make dancing in love and lust with his mother (on the left below).

After his breakdown where the dancing disorder is at its most chaotic – in the Prince and in the social body, the prince is retired by his Mother and a doctor and nurses to his bedroom, now looking like a padded cell. This scene is wonderful but cruel. At its highlight, the Swan is birthed from the base of the bed on which the Prince lies as if emerging from an egg. The Swan is wounded and bleeding. The swan corps who wounded him emerge severally from under the bed and the wings but when they make a force as a social body it is one antagonistic to both male leaders. The swan body are killing their king and his compere, even though the compere is of higher status than they. On the left the visceral coupling of Swan and Prince occurs on the bed, the Prince pleading for fulfilment, Top right we see how Tchaikovsky’s tortured music is dances , whilst you see the ominous body of the swans corps bottom right.

This ballet is superb and does not really feel like Swan Lake, as it is socially imagined in our traditional culture. However, perhaps when we say a thing like that we compare a true reimaging of the piece against the excrescences of a tradition that, however beautiful, is repetitive and organised institutionally rather than primarily creatively. For me the Matthew Bourne piece is queer art of the highest order that releases that force in a great queer artist of the past – Piotr Tchaikovsky.

Luke Jennings’ review in The Observer (already cited) would be a good place to end, even though he, unlike me, does not want to own the piece for a long neglected queer community as its OWN, asking questions we need to ask about family, desire, prohibition and the desire to break free and find authenticity where none may exist, for it has to be invented and imagined. He says it simply though and fairly, when taking further the point that the Prince ‘falls in love, only to be viciously rebuffed when the Swan’s human double materialises and that ‘the Swan, who may or may not be a figment of his imagination’. Comparing Bourne’s production to past tradition, he says:

Bourne, by contrast, asks hard questions of the ballet, whose first performance in a form that we would recognise today (with choreography by Marius Petipa and Lev Ivanov) took place in St Petersburg in 1895. Why might a man imagine himself to be in love with a swan? What form would this swan take, and in what imaginative realm might such a strange love story unfold? … Swan Lake today is all too often a beautiful ritual, all too rarely a compelling drama.[3]

I wanted to write this in honour of a great experience but have I let it and myself down? Life is too short to worry except about the questions this great and artistically creative production of an original work, equally great but different, causes to arise.

Love

Steve

[1] Lewis Segal (2019) ‘Review: Why Matthew Bourne’s male ‘Swan Lake’ is still radical and relevant, 24 years later’ in The Los Angeles Times (DEC. 6, 2019, 1:13 PM PT) Available at: https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/story/2019-12-06/matthew-bourne-swan-lake-ahmanson-los-angeles

[2] Luke Jennings (2018) Review: Matthew Bourne’s Swan Lake review – a wild ride Sadler’s Wells, London in The Observer (Sun 16 Dec 2018 08.00 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2018/dec/16/matthew-bourne-swan-lake-review-sadlers-wells-little-prince-ballet-review

[3] Luke Jennings op.cit.

3 thoughts on “In 2018 Lewis Segal wrote in The Los Angeles Times of Matthew Bourne’s ‘Swan Lake’ and praised ‘the members of the swan corps: feathered, bare-chested virtuosos whose sense of menace kept the work from collapsing into short-lived camp’. Is this a work that STILL demands attention from everyone in the queer community. I saw it on 13th September at the Gala Cinema, Durham City, UK.”