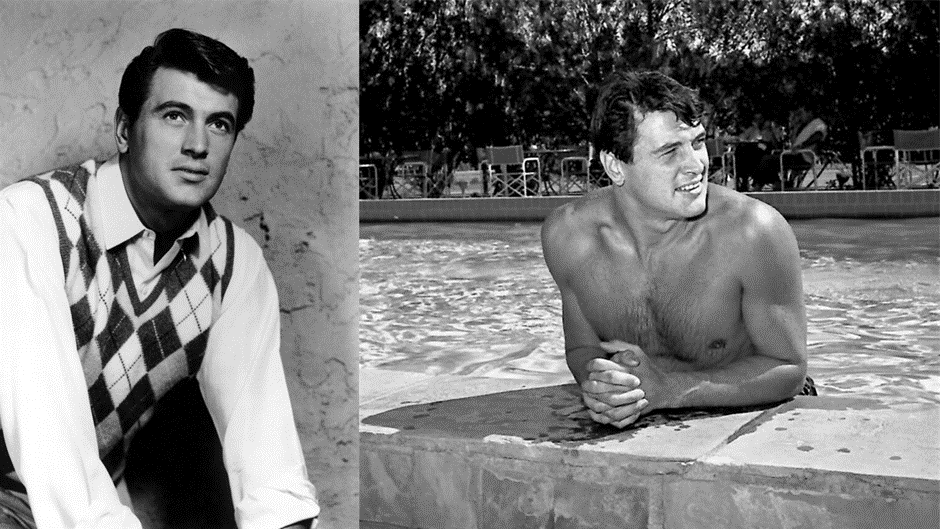

As I was reading Mark Griffin’s (2018) All That Heaven Allows: A Biography of Rock Hudson (New York, Harper), I think I concluded that Rock Hudson was neither insightful nor supremely talented though he was sometimes a very good actor and performer indeed (though also sometimes not so good and – by his own estimation – could neither sing nor write with any conviction). However, now that I begin to reflect on his significance in queer history, his story and life-performance values and skills illustrate that the art of passing was never the opposite of the supposed necessity (it is supposed thus by me but not for everyone) of coming out. His most famous film, Giant, is an exemplary illustration. And, of course, he could look lovely too.

It would be difficult to treat Rock Hudson as an ‘auteur’ of his own life, and beyond the network of film production companies, moguls, directors (many of whom did consider themselves auteurs as we shall see in the case of George Stevens in Giant [or Douglas Sirk in various films that starred Rock Hudson]), cast grouping, agents (especially that fine handler of the art of passing-as-straight for others, Henry Willson) and social institutions (including family) and ideologies (including families too including the idea of chosen families). But actors have to handle scripts that they are handed – whether these be the script of a film, even ones that play close to things we think to be true of an actor’s life or the script which is our internal psychological mental schema of how everyday life is lived.

Thus a boy born Roy Fitzgerald is persuaded to identify instead as Rock Hudson. Michael Kearnes speaks about that fact in the light of the fact that he took a different route in his acting career and in making that career relate as well as he could to how he saw his own life-story. Griffiths names Kearnes as ‘one of the few openly gay actors in Hollywood’ with a ‘shades-up policy regarding his sexuality’ but he also makes it clear that he thinks that this ‘shades-up policy’ also ruined Kearnes’ chances of a grand career in Hollywood like that of Rock Hudson. Rock had a dream when he was young of being in the spotlight, and it was a spotlight that he wanted to realise in his own life regardless of its cost to what you might call integrity (though that is a callus way of putting it). In the dream lights that played upon him then made him feel as if he were ‘being filled with a most brilliant light’. He interpreted (although perhaps in hindsight) that dream as meaning that he was ‘destined to be something special … a star, if you will’.[1] Kearnes puts this aspiration into a rather different shade or nuance, however. His summary of Rock as a colleague was that he:

… was a brilliant actor, though not necessarily on the screen. His most brilliant performance was playing ‘Rock Hudson’ all his life. I think the acting he did off screen required more work, more transformation. Then you start to wonder … Who would he have really been if Roy Fitzgerald had been allowed to exist? What would he have really talked like? I mean, from the very beginning of his life, this is someone who had to act just to survive.[2]

The issue Kearnes raises that a prescribed performance is the cost of survival in more than the obvious (that totally inactive beings cannot survive except through external supports) sense. Kearnes thinks that if ‘Rock Hudson’ is a constructed role, with a predictable plot and sometimes script, it is one whose symbolic role is not one chosen by its enactor but by powerful forces external to the enactor, the sound made by whose very ‘voice’ is prescribed by characteristics others think appropriate, And what is appropriate may exclude even more than the options a queer Roy Fitzgerald would have developed in order to survive as someone more authentic than Rock Hudson is suggested to be. Distant from all of the father figures that his mother, Kay provided for him no meaningful relationships with an older male developed in Roy’s youth according to Griffin. His putative biological father, Roy H. Scherer, deserted the family, whilst his nominal stepfather Wallace Fitzgerald was a violent and homophobic ‘drunk’ in the word used of him at the time by family members. When Kay left Wallace, Roy stayed a short time with Scherer, though even at close quarters ‘the distance between them remained’.[3] However, I think it would be as mistake to drive home any link between an absent male role model and Rock Hudson’s developing sexuality. The stereotype is just too convenient and the evidence lacking.

In summer 1947, when young ‘Roy’ was near the end of his twenty-first year of age, he experienced his first recorded relationship with a man of 33 years of age. Ken Hodge loved Roy but he also ‘liked sailors, and often had them lined up in living room’. Ray’s motives in the relationship seemed to be linked to Ken’s limited powers to advance his acting career and he dropped him quickly once an agent of some greater clout, with a good track-record, came on scene, Henry Willson.[4]

This pattern of usage of people in career terms, which would be replicated with him by younger men in the future was established then well established, but Willson exerted a price for his services – not only in fees but sexual services – and that secret part of his cost to Ray would make him a better conversion factor into the enacting of what it means to ‘pass’ as a heterosexual than ever exerted before by those who wanted him to be an authentic heterosexual like Scherer. Griffin calls him – in relation to other people than Rock Hudson the ‘ultimate “manizer”’. And Ray Fitzgerald, to Henry Willson, he appeared ‘everything he could have hoped for in a client – devastatingly handsome, extremely ambitious, and almost effortlessly manipulated’. The process involved instruction in the eradication of ‘effeminate traits’ such as, in Griffin’s words ‘the girlish curl to his upper lip whenever he smiled’, and a ‘flutter giggle’ that just didn’t pass as manly laughter. In all of this process, then, we can feel the man being drawn out of the boy as a set of behaviours following a plot named ‘becoming a real man’, and a script that ensured that even vocal delivery had a low enough pitch (there were rumours of surgery to achieve that performance capacity). [5]

And it wasn’t enough to stress the stereotype of a male entirely conditioned by his biology, Rock would only be allowed roles that male producers thought his female audience wanted. Attracted to the idea of playing a ‘maniacal alcoholic’ and ‘conniving nympho’, Kyle Hadley, in Written on the Wind for Douglas Sirk, publicity manager David Lipton said; ‘his fans would not accept his doing anything shoddy’. That juicy part went to Robert Stack – all virulent machismo – with Rock in the role of a dependable but boring, lantern-jawed but self-sacrificial Mitch Wayne.[6]

No wonder Rock must have wondered; ‘I don’t know how long I can get away with this act’, when he was given that line to speak as ‘a playboy composer, Brad Allen’ in Pillow Talk in 1959. But the line really needs more context in order to see how far from simple the act of ‘passing’ (as straight) was for Rock. For it was a line spoken when Brad is himself supposed to be playing:

Rex Stetson, a Texas longhorn who seems more than a little light in the saddle. Telltale pinky extended, he sips his martini while revealing a mother fixation and more than a passing interest in Doris Day’s interior decorating’.

Griffin is excellent in interpreting the significance of this ‘illusion-on-an-illusion’ in this moment of his career, which according to him starts ‘a steady stream of what seem like self-reflexive in-jokes’: beginning with ‘a predominantly gay man’ enacting ‘a straight man who is impersonating a gay man’.[7] But since this too was his first light comedy role, as such, the dissonance between reputational image as a ‘woman’s manly man’ and on-screen enactment could easily be explained by this paradox into which comedy so often dives, including female impersonation. Not so though a much later film, A Very Special Favour in 1965. This took the game even further, though given the psychological bent of the film.

It concerns a psychotherapist, Dr. Lauren Boullard, played by Leslie Caron who appears to have some interest in saving gay men from themselves. Rock plays a playboy (what else,) named Paul Chadwick, asked by Boullard’s father to save her from marrying Arnold Plum, an effeminate former hairdresser. He therefore passes himself off as a much more interesting case of homosexually tempted beefcake, receiving responses to his story of shutting himself away from the ‘sex-craved women’ he says pursue the use of him as a ‘sex toy’ inside his flat, like this from Caron: “Hiding in closets isn’t going to cure you,” the good doctor tells Chadwick. “Your anxieties about women are reaching the psychotic stage.” The medicalisation of ‘homosexuality’ and its common-sense ‘cure’ by exposure to women must have rung many bells with a society increasingly convinced of Skinner’s behavioural therapies. Griffin cites Vito Russo’s classic The Celluloid Closet here to suggest that it is clear the project to which Rock is being subjected here, admittedly with his own co-operation and perhaps desire to tread a tight-wire over his fears of exposure, ensures that his; “masculinity is on trial throughout the film, its authenticity under constant scrutiny”.[8]

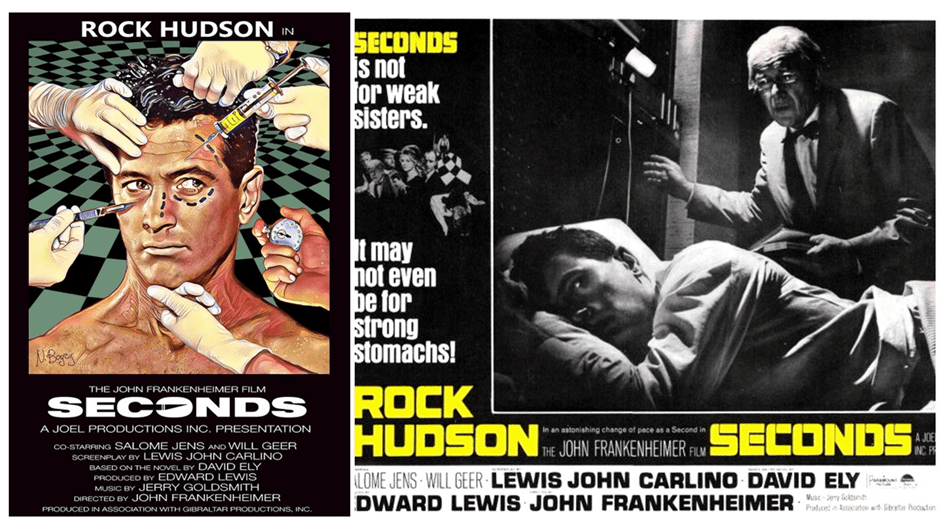

A year later even (1966), he defied the latter by taking the role of a man who has been metamorphosed into looking like him by surgery in Seconds. Though not dealing at all with queer issues – the transformation of a ‘playboy’ (again) is affected in order to be more successful with women (though the director, John Frankenheimer, was influenced by a play-script that did, a play called Epiphany. But the idea of escaping one personality and becoming another and acting it which fascinated Frankenheimer appeared to drive Rock into mental breakdown, as his friends thought it might, and contemporary observers interpreted this as a result of the actor confronting the issues of ‘living a lie’ and, in this film, from now on in Griffin’s words, bravely attempting ‘to unlock a more vulnerable side of himself’.[9]

As he aged, though he ensured popularity with female audiences for popular TV with Macmillan and Wife at the same time, he himself felt he dared even further, though put off by his male lovers and camp followers. Playing close to the wire was much more apparent, though again in comedy but comedy in his wish to accept an offer to play an indubitably gay character masquerading as not so in the Broadway version (the actors pictured below are those in the film version) La Cage aux Folles. He turned it down, however.

That he did so may have been influenced by occasions when he was publicly called a ‘Faggot’ in a public place, as described by Griffin in two places I can no longer find in the book, the increasing complexity of his love-life (if it can be called that – of which more later), and, the open scandal of his association with James Barnett, about which I have adverted in another blog, so won’t repeat here, but include a collage from that blog, which can be read at this link.

But the wish to examine the phenomenon of passing goes deep into Rock Hudson’s life, though I doubt he would have articulated it in so many words – and perhaps could not do so.

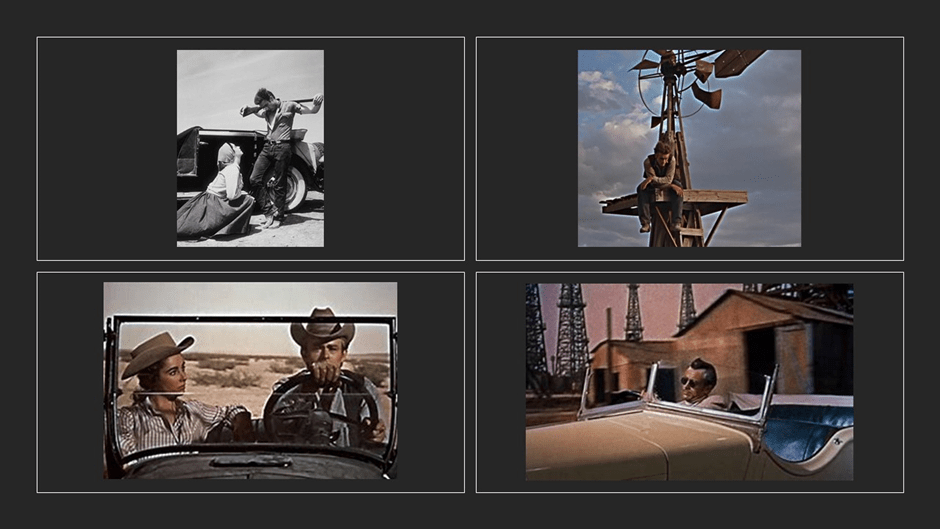

I watched Giant for the first time in my life, seeing the full film, to test this idea on myself on the 12th of September 2023. I took 17 pages of notes whilst I did so, but much was about other aspects of this flawed but genuinely and deeply interesting film, not only because of the unspoken issues I will go on to deal with in it relating to the performances of both Rock Hudson and James Dean, and their relationship up to the latter actor’s death before the end of the film.

The film also attempted to examine gender roles through the role of not only Elizabeth Taylor but a strong cast of women. For instance, the character played by Rock, ‘Bick’ (Jordan Benedict) says to his new wife when she accuses his male friends of prehistoric misogyny that she is ‘pretty repulsive at times’ and likens her to both Joan of Arc, condemning her talk as ‘preaching like Carrie Nation’. Its examination of racism is even more telling and central if fragmentary and perhaps ‘resolved’ glibly and over-sentimentally.

But Giant is really about men who long to be big men, who will, whatever their true situation, play at passing as big men by looking like they do. Benedict impresses his Eastern peers by emphasizing the size of his ranch (named Reata – the word means lassoo – hence the logo) acreage – 595,000 acres – (and ranches generally in the South and Texas in particular) and the vast number of the herds of beef he farms on them.

Unmarried – until Lesley (Elizabeth Taylor), a smart Eastern American, lassooes him – despite his masculine pretension, people know his ranch is run by his sister, Luz. Luz describes brother Bick as a man who ‘would rather herd cattle than make love’, knowing that his masculine self-image is somewhat tarnished, constantly afraid of the contrast of other men, even the poor white ranch-hand, Jett, whilst she herself prefers a masculine self-image. Though he impresses Eastern landowners peers in their green county of small estates and English manners (mainly because of the size of his agricultural holdings, this respect is not shared by the ‘poor-white’ ranch hand, Jett Rink, his employee. This may be why he constantly tries to ‘fire off’ Jett except that Luz, his sister who Jett calls ‘Madama’ and says, ‘she likes me’, keeps re-employing him (and will indeed leave him a legacy of land in her will).

Later in the film, called into the house by Bick – actually to discuss his legacy – Jett petulantly says: ‘Boy, howdy, nobody’s firing me’. Jett, played by James Dean, who Griffin tells us was hated by Rock as much as Bick hates Jett, jeers at Bick with the taunt, ‘just tell me who is boss here’ (for he answers mainly to Luz). When leaving the farm on a task he says: ‘Ain’t nobody that s king in this country’. When Jet’s land strikes an oil gusher, he knows he will be a rich man, makes a pass at Lesley before Bick’s eyes and when challenged in fight describes Bick as ‘Touchy as an old cock’. The masculine size contest could not be clearer, though of course he means a cock-hen, ostensibly.

Rock as Bick looks mighty impressive, especially in front of a painting of his big land, but it can’t be sustained.

Both men constantly attempt to pass as the best of men in their country, and both see that requiring validation by Liz Taylor’s character, Lesley, especially after the death of Bick’s sister Luz. To Lesley, though not directly and sotto voce, when she orders him to visit the sick baby, Angel is his name, of her Mexican tenant-workers, Polo Obrégon and his wife, even before Luz’s death is known he says: ‘You are the boss. You know it too, don’t you’. Taking the smallholding of land given by Luz, instead of selling it back to Bick at twice the value, he fences it and calls it ‘Little Reata’, just to emphasise that even the Reata ranch is no longer as ‘big’ as it was and that Bick has a challenger as Big Daddy. Both men play up to Lesley and know she does not let them quite pass as the big men THEY think themselves to be; when Lesley returns to her father’s estate in the East he finally realises he must ask her to return to a humbled man to her ‘beat-up cowhand’ (humble pie indeed).

His children disappoint him. His son Jordy cries on a horse as a child and later wants an education and a role like that of maternal grandfather – a doctor. His elder daughter and her fiancé, though a true ranch-hand unlike Jordy wants not to be the owner of a big patriarchal ranch but a ‘small place’ of our own, for ‘Big stuff is old stuff now’. Jett however just gets bigger, owning a vast range of rows of oil gantries, building an airport and huge hotel, setting up a cavalcade in which he rides in as the ‘emperor himself’ in Bick’s words, followed by Bick’s youngest daughter, called Luz after her dead aunt, as ‘Queen of Jett Rink Day’. Clearly the triumph (over Bick and Lesley could not attempt to be clearer).

But Jett Rink too is just passing himself off as the new ‘big man’ of oil firm JeTTexas, to which he has renamed ‘Little Reata’, wen legally challenged by Bick, now a man as big as a State. His bigness is the bigness not of land but of motor cars and what runs them and with them and other vast phallic machines he is constantly associated. Alone though, he looks pretty small. At the end, drunk and rejected by young Luz as a partner, Bick says: ‘You ain’t worth hitting’. He slumps over the table when asked to give an after-dinner speech as ‘a legend in his own time’.

Jett – a lonely young-boy-cum-man made to look big from the money in cars

I hope this account of Giant makes the point that the analysis of masculinity as an illusion – make up often of pretensions to size and dominance in external factors – land, cattle, motor cars and the oil gantries hat drive them, even the tradition of big stretches of traditional times in big names like Benedict – are illusory. We all pass, and what will challenge us is that time passes too and will take our tokens of size with us, even our physical size. The film itself, in George Steven’s conception need to create great artificial sites of impressive size as the site shots below perhaps will show:

And, if this blog is worth anything, it is because it shows that Rock Hudson was a man whose queerness got expressed in the doubts he always ALLOWED TO BE EXPRESSED by the scripted roles he took, where he was never what he seemed or at least less than he seemed, and that, in particular, pretension to masculinity was the least of one’s personal prizes. Griffin makes the point, but not about Giant, as I do above, that it was not sexual politics alone that was sometimes queered by the admission that much of its pretentious roles were illusory role play, but that his preference was to play a ‘socially unacceptable lover’, and to an extent Bick is that too. Of course Bick is more unacceptable than Jett in Giant. Was this why Rock was so jealous of Dean and the wonderful shots of a man isolated in his illusion that he relished himself? So jealous was he that he blamed himself for wishing Den dead when he was killed in an accident before the end of the film. Griffin sees the archetypal role of the ‘socially unacceptable lover’ in a Jett Rink kind of role – Ron Kirby, the gardener in All That Heaven Allows: ‘Ron is … too young, too working class, too earthy’. Griffin says he was ideal for that love because he was ‘a deceptively macho homosexual who could easily pass for straight’.[10]

I think though that the tragedy of Rock’s life lay in the intrinsic nature of the star system that meant that ‘passing for straight’ meant that only short-term relationships could ever be sustained and that with men who abused his kindness, and pandered to the way in which it was easy to paint him as satisfied by rent-boy affection alone.

With Marc Christian

Griffin never quite says that, but it seems to shout out from the perfidy of Lee Majors, when Rock was diagnosed with HIV infection and then AIDS[11], though of the was in denial himself, and the mess of his last relationship, with Marc Christian. The latter ‘denied that he had ever been paid for sex’ but his early, and possibly not long before he knew Rock, life of prostitution of a kind became public knowledge. When Rock moved on (he always did it seems) to what he felt was true love for Gunther Fraulob, he feared taking it further as he had in the past since the ‘presence of yet another young hunk was bound to stir things up’.[12]

I rather love Rock myself now. But wouldn’t it be hopeless. Had enough of that.

With love

Steve

[1]Mark Griffin’s (2018: 408) All That Heaven Allows: A Biography of Rock Hudson New York, Harper. These are the last words in the book.

[2] Cited in ibid: 359.

[3] Ibid: 27

[4] Ibid: 33-35.

[5] Ibid: 39 – 41.

[6] Ibid: 154

[7] Ibid: 198f.

[8] Ibid: 255-6

[9] Ibid: 261- 264.

[10] Ibid: 127 – 130

[11] Ibid: 372ff.

[12] Ibid: 367-371

5 thoughts on “As I was reading Mark Griffin’s (2018) ‘All That Heaven Allows: A Biography of Rock Hudson’, I think I concluded that Rock Hudson’s story and life-performance illustrates that the art of ‘passing’ was never the opposite of ‘coming out’.”