‘I want to be ugly on the cover of Time ‘.[1]This was to be the first part of a series of blogs on narcissism in the queer art, politics and representations of human feeling and attraction in Rainer Werner Fassbinder. This part examines Ian Penman (2023) Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors, London, Fitzcarraldo Editions. Other parts are unlikely.

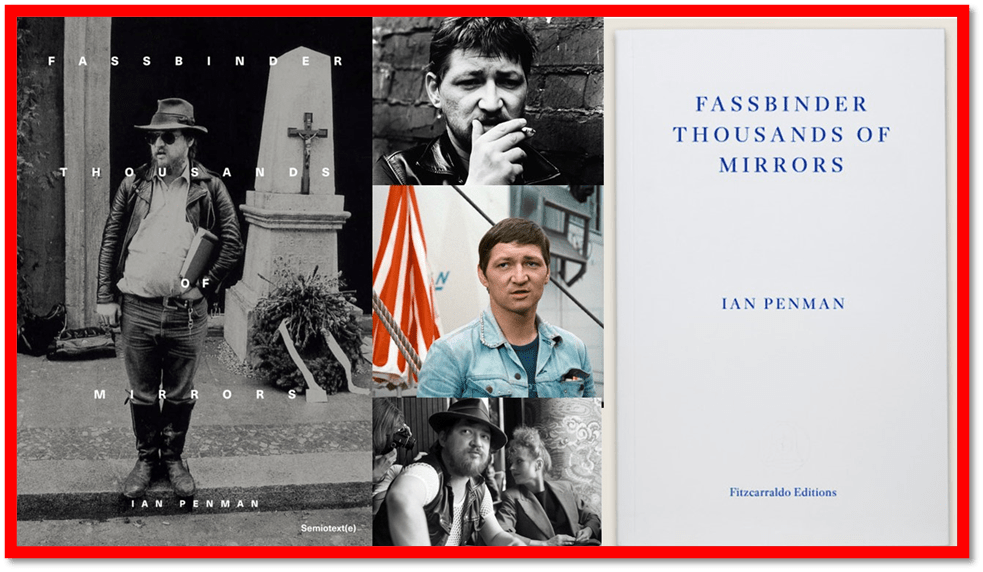

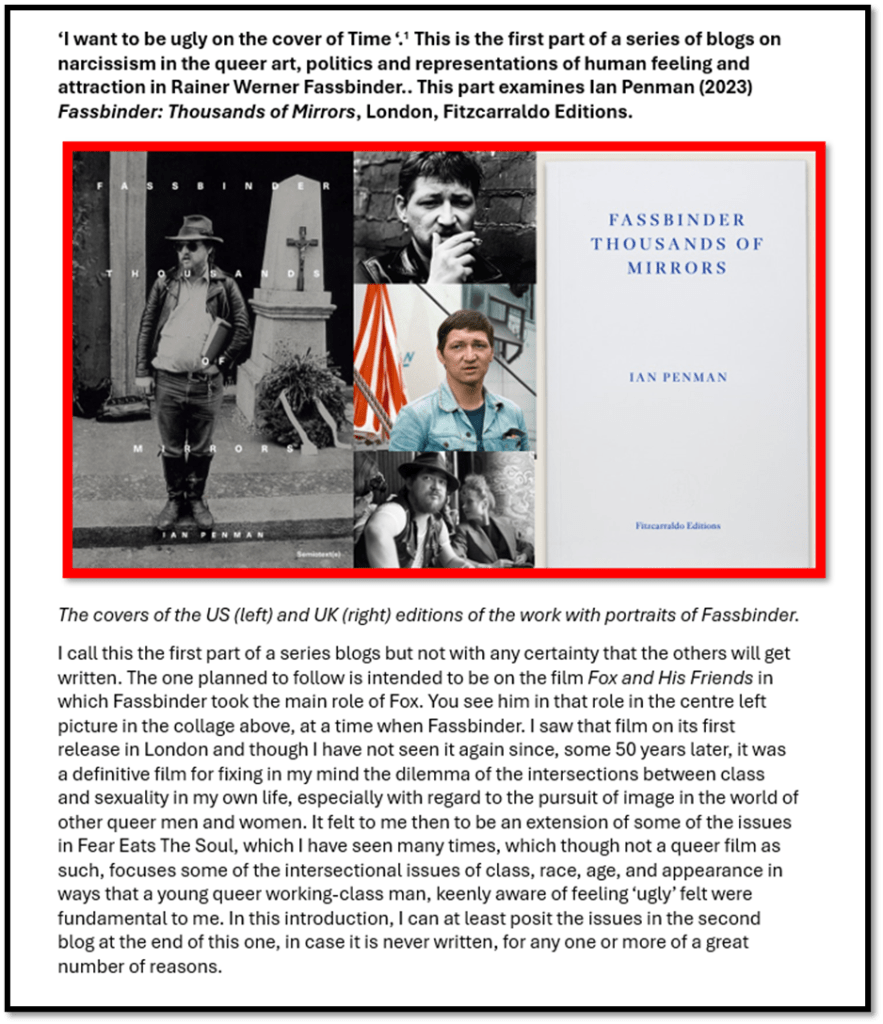

The covers of the US (left) and UK (right) editions of the work with portraits of Fassbinder.

I called this the first part of a series blogs I intended to write but not with any certainty that the others will get written. I now know that they won’t. The one planned to follow was intended to be on the film Fox and His Friends in which Fassbinder took the main role of Fox. You see him in that role in the centre left picture in the collage above, at a time when Fassbinder put his own image up for barter. I saw that film on its first release in London and though I have not seen it again since till now, some 50 years later, it was a definitive film for fixing in my mind the dilemma of the intersections between class and sexuality in my own life, especially with regard to the pursuit of image in the world of other queer men and women. It felt to me then to be an extension of some of the issues in Fear Eats The Soul, which I have seen many times. Fear Eats The Soul though is not a queer film as such: nevertheless, it focuses some of the intersectional issues of class, race, age, and appearance in ways that a young queer working-class man like I was, also keenly aware of feeling ‘ugly’ as Fassbinder did, and sought to amplify, felt were fundamental to me. In this introduction, I also posit the issues in the second blog that will never get written at the end of this one, for any one or more of a great number of reasons.

Penman speaks about Fassbinder using strange and queered methods with which one never quite feel comfortable. He divides the book into numbered sections, some only a sentence long, others covering a few pages. Sometimes they are direct quotations, even the most obvious and best known one: the stuff of A-Z Quotes fancy, such as the one I give below, which appears in Penman’s book as section 283, and is followed by a comment on that statement of Fassbinder’s, or one like it, by William Roth, the writer of the first annotated filmography on Fassbinder.

This quotation forms section 283 of Penman’s book, ibid: 107

The framework that explains both Penman’s reading of this quotation, and Roth’s too perhaps, I read this quotation that precedes it in his book, as its section 282:

Is the Fassbinder worldview just an abyssal reflection of the capitalist one he supposedly execrates? Does he merely reproduce capitalism’s rotten schema through a mirror darkly, upside down inside his camera viewer? The lifeless scene surveilled by a diagnostician’s cold, insectile gaze. A cruel world and its double. The mathematics of need and abasement. An inhospitable pitiless place.[2]

This paragraph is all questions but I think they are probably rhetorical ones that play the role of statements. Elsewhere Penman lets rip with his surety about Fassbinder’s basic philosophy of life lived only in inescapable oppression to capitalist values: ‘Struggle is futile, alienation is final and insolvable’.[3] He can ‘off the top of his head’ recall only short passing events occurring to five characters (from three films) that might be justly called ‘moments’ of ‘hospitality, charity, uncalculatingly warmth’: ‘Emmi in Fear Eats the Soul, Mec, Eva and Mieze in Berlin Alexanderplatz; Robert in Veronika Voss’.[4] Chris Molnar in The Los Angeles Times takes Penman to task here, at the end of his review, for seeing Fassbinder as summarised in his tendency to create:

… the no-way-out paradoxes of Fassbinder’s characters as perhaps the projection of a “stunted boy-man, used to fetishizing his own pain, but wholly without empathy for the often far greater pain of others?” Here I disagree—the empathy I find in Fassbinder’s films is greater than that in any others. And if the artist, any true artist, remains a child, it is also to have the “taint of innocence,” as Penman calls it, to see and embody the “hope of love and its distant mirage shape” that manifest in unconditional empathy, the kind we need in our own no-way-out paradox, that of being alive in a world full of hate and pain, that leaves us open to hurt but gives us power nonetheless.[5]

This is a knotty paragraph of Molnar’s but I think I agree with regard to both its judgement of Penman as a critic recreating a Fassbinder without humanity, a monster, and the overall effect of aching and unconditional empathy in a definitively cruel world, one based on the values of self-interest alone. There is a less knotty conclusion about what Fassbinder actually was to the culture as we, as I at least, lived through it in William Harris’s fine essay on this book in the left-wing radical online magazine, Jacobin. Harris admits that the endings of Fassbinder films are bleak – having just re-watched Fox and His Friends, I can attest to that: but films are not just their endings. Moreover the ‘end’ of a film is that word in its teleological portent (its purpose or drive to meaning,. Otherwise all the films might and could mean is nothing other than just a bleak conclusion in a deserted underground station with boys robbing the cold corpse of Fox, as played by Fassbinder himself.

Harris writes (with my emphases within the quotations):

The Fassbinder films that speak to us now do so … because they seem, in some resonant way, pre-postmodern: they have heart, they’re told simply, and they believe in moral and political meaning in a way that we, too, are beginning to, in similarly garbled, frustrated ways.

He does not dismiss, as he continues, Penman’s project – far from it – but he does think it must be interpreted differently. The aim is to:

…. mark out what in Fassbinder it might be time to say goodnight to, and to recall that there remains a special world of feeling and ruthless political insight in many of these films, even if they end in some acrid emotional desert. Something, in the present, worth returning for.[6]

The return to a moral fable seems important in Fassbinder. Penman overdoes the feeling that Fassbinder was just a spoiled child. Indeed when Penman deals with Fassbinder’s debt of learning to Douglas Sirk he rather diminishes Fassbinder’s ‘first response’ to the ‘very basic and human’, where he ‘not afraid to use words lie “sad” and “desperate” and “beautiful”’.[7] When Harris quotes the same passage as the words used by Penman (taken from an essay by the director in New Left Review in 1975) he adds a prior paragraph and more context that really, though Harris does not say directly, means that Penman’s interpretation is unsustainable. Fassbinder’s ‘first response’ to Sirk is part and parcel of his subsequent responses to Sirk’s innovations of form and technique, borrowed anyway from the Expressionism of the Germany directors like Sirk fled to escape Nazism and maintain their freer expression of a critique of the anti-humanist neo-liberal capitalism. The appreciation of the star role even of Rock Hudson by Fassbinder is meaningful (see my blog on Hudson at this link). Harris says:

From Sirk, Fassbinder learned a certain simplicity, a soft moral sensibility, a humanist feel for the sadness of life. A way to make political films out of everyday scraps. You get a taste of this in Fassbinder’s massively charming essay on Sirk, written in 1975 and republished in New Left Review.

Jane Wyman is a rich widow, Rock Hudson prunes trees for her. In Jane’s garden a love tree is in flower, which only flowers where love is, and so out of Jane’s and Rock’s chance meeting grows the love of their lives. But Rock is 15 years younger than Jane and Jane is completely integrated into the social life of their small American town. Rock is a primitive and Jane has something to lose: her friends, her status she owes to her late husband, her children. [. . .]

This is the kind of thing Douglas Sirk makes movies about. People can’t live alone, but they can’t live together either. This is why his movies are so desperate. All That Heaven Allows opens with a shot of the small town. The titles appear across it. Which looks very sad. It is followed by a crane shot down to Jane’s house, a friend is just arriving, bringing back some crockery she had borrowed. Really sad! A tracking shot follows the two women and there, in the background, stands Rock Hudson, blurred, in the way an extra usually stands around in a Hollywood film. And as her friend has no time to have a cup of coffee with Jane, Jane has her coffee with the extra. Still only close-ups of Jane Wyman, even at this stage. Rock has no real significance as of yet. Once he has, he gets his close-ups too. It’s simple and beautiful. And everybody sees the point.

Imagine having this heart-on-the-sleeves sensibility, this precise formal imagination, and implanting it into a ’70s/’80s West German world of grunge and sleaze, corrupt capital, leftist terrorism, cybernetic media, gay fantasia. Sweet, bleak, and garish, all at once.

Imagine that only if you do not, as Penman does, interpret this emotional negation of capitalism as antagonistic to the analysis of capitalism in Fassbinder also that has a cold clear objectivity behind it. The two interact with each other, showing the deficiency of one of them alone. Harris’ essay is brilliant also in showing how and why Penman constructed Fassbinder as he did, in Harris’s words. Penman was born out of that crisis in the left when belief in class was shattered and the left looked to newer, younger models of political discourse, those of the young – not a past caught in contradictions o that the present became what Stuart hall called the ‘Great-Moving-Right’ Show. Politics took on rainbow alliances of the dispirited, marginalised and unrepresented looking to issues around race, sex/gender and sexuality for models of a new Communitarian politics, to feminism in particular. The young vaunted a politics that could be confused and without a grand narrative theory behind it, like Marxism that was libertarian with a tendency to hedonistic experiment. Of this movement, Penman, an intellectual dominant in the New Musical Express, was typical. But as he aged and began himself to realise the advantages of humanist neoliberalism to his generation, with others, there:

… came to be two Penmans, the first young and excessive and drug-spiked and beamed-in from some far-off, pop-mod planet, the second old, reflective, patient, and movingly humanist. …

In a veiled way, he became a critic who reflected on himself — his own history, youthful folly, highs and lows — by writing on the lives of others. Why did so many of last century’s great creative lives sputter out in a haze of drug addiction? Why did we ever find this romantic, and why do we now reduce it to something entirely joyless? What do we want to rescue and marvel over from the ruins of postwar and ’70s/’80s culture, from that transitional moment when high and low cultures conjugated, and class felt both solid and shifty? And what do we want to discard, face up to, and consign to the past?

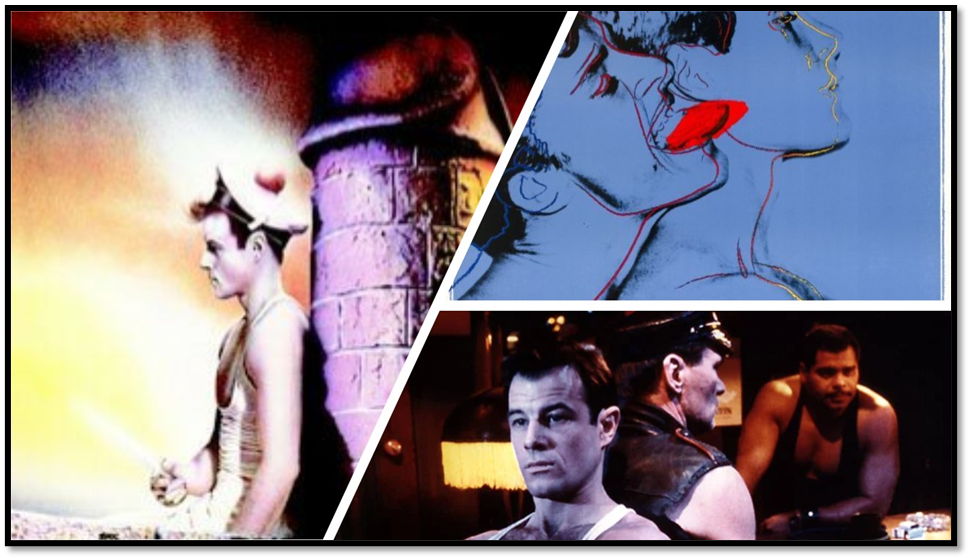

The young man who could not give up on excess and brashness that he paints as Fassbinder was him to a certain extent, a side to himself , a double, he wanted rid of. Hence the interest in doubles or doppelgangers in Fassbinder, and their genesis in real or imagined narcissistic mirroring processes. Fassbinder’s politics get somewhat lost in psychological explanation thereon. Look at the classic stills in the collage below from Fox.

Young gay men, such as Philippe and Eugen in the shot in the boutique, use each other and the mutual desire potential between them to see themselves in each other’s gaze. They use each other as a mirror. Because there is a real mirror Eugen is doubled in the still, with one of him looking directly at Philippe, the other looking above and askance, the self in the mirror. In the film the facially regular gay men use the camera lens in a similar way as Fox (Fassbinder) does in the shot on the left, He sort of seeks the gaze of another man but sort of dismisses it too, perhaps fears it. As the film progresses, and Fox’s winnings on the lottery are spent, people see him differently; as a drunk, as ugly, as having a strange face. The construction of looking is central in the films. Fox is the last role Fassbinder played, and though he is a lithe young man, his face is often seen as distorted and lacking conventional good looks. There is nothing ambiguous in his figure however. Fassbinder / Fox makes a good nude displayed in mirrors that is appraised positively many times.

The problem for Fassbinder is that narcissism raised in himself an ‘other’ that he feared: an ugly fat man unable to attract love or admiration that even Fox may see people seeing in him, as when the American GIs ask how much he pays for sex with them. And after he starred in Fox, Penman makes much of Fassbinder becoming fat: bloated indeed is the word he uses. Even in 1975 as Fox and his Friends came out Fassbinder’s face had filled out from when he was acting in the film he now introduced as its director:

German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder 1975. (John Springer / Corbs via Getty Images)

Molnar makes the contrast between, following Penman’s example of Fassbinder in his documentary Autum and Fox:

Autumn gives us Fassbinder’s increasingly unruly hair, belly, and even his flaccid penis, unceremoniously visible under a white T-shirt. Only three years previous, in his final starring role in one of his own films—as the titular lottery-winning hustler Fox in Fox and his Friends—he was handsome, full of the raw magnetism that made him the best actor to star in his own films, hilarious and unpredictable, walking strictly to a beat you can never learn. Here he’s still magnetic, …

Despite the fact that Fox is often described as ‘ugly’ in Fox, once he is poor and desperate again, Molnar is right to find him rather sexily ‘handsome’. The problem is that narcissists cannot be both. They must be adorable without nuance. And that is the asexual ceremoniously visible Fassbinder of Autumn three years later – just plainly unattractive. For Penman this was an aim, partly conscious of Fassbinder’s, and hence the brief quotation in my title. Here is the context as quoted by Penman:

‘Growing ugly is your way of sealing yourself off.’

‘Your stout, fat body, a monstrous bulwark against all forms of affection, which only makes you sceptical … The child in you screams at the bulwark, screams at your nightmares for love and harmony.’

‘Grow ugly and work. …I want to be ugly on the cover of Time – it’;; happen and I’m glad about it … – when ugliness finally reclaimed all beauty’.[8]

The fear of being ugly as society sees you is the fate of the marginalised, neglected and abused for whom no reparation occurs from ultra-resilience, accident or conscious support or ‘therapy’. However handsome you act or as perceived, the chances are the one perception of one as ugly will determine more than a thousand forms of praise or visible admiring gaze, even of yourself by yourself in a mirror. The evidence of one’s eyes or others is doubted. Ambiguity or nuance of judgement is denied of cover of the recognition of one’s true state of ‘not being good’, for being ‘good enough’ is still lacking goodness and o a narcissist, it’s all or nothing. In my view this occurred to the stigmatised all the time, but was a product of interactions between contexts, including the contexts of real or perceived judgements, even implied in the gaze, and unhelpful social cognitions of what constitutes beauty or attractive quality.

That certainly marred my own childhood, born and early aware of being what others taught me was a ‘freak’. Penman’s Fassbinder embraces this ogre-like future self – better not to be unsure how people see you and ask why. Just accept that being ‘ugly’ has ‘reclaimed all beauty’ there possibly could have been.

Penman says everything about Fassbinder had to be ugly. His political ideas had to be ranting at the hypocrisy of others to avoid any intimacy he says. In the footage of Wizard of Babylon Penman describes him thus: ‘Fassbinder now is pasty and bloated, visibly stoned, nodding out, a victim of unrestrained appetites, like a doomed character in one of his own films’.[9] In 1977 we saw the process happening more than 1975:

… unreadable expression, possibly reflective and thoughtful or then again possibly just posing or momentarily blank; his face not yet bloated even if his belly is already a substantial mound; his hand halfway inside the waistband of his dark trousers, worn with easeful braces now not a constraining belt; …[10]

Penman loves seeing the process And loves describing it. In 1882 or ’83 even in the giftbook of photographs for Querelle of Brest, there is ‘one great black and white photo of a bloated, ruminative-looking RWF’.[11] There is a truth in saying that Penman’s joy in these descriptions is so excessive it is itself ‘bloated’. It is also true that not everyone will see Fassbinder as ugly at any state of bodily appearance. The fear of looking and being ‘fat’, to the point of willing it, does not, and never will solve the multiple ways that people might see, interpret or be attracted or repulsed by you.

And the great thing about the films is that this of true of all criteria and norms that guide attraction and the eye or beauty.

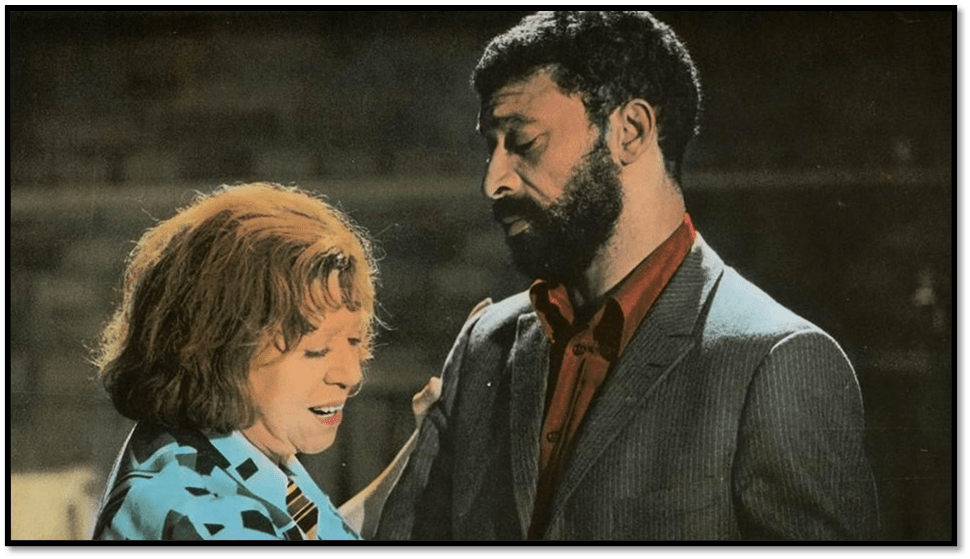

In Fear Eats The Soul, a Black Moroccan immigrant, notoriously beautiful in the form of the actor who also plays the man for rent in white queer Morrocco in Fox and His Friends, is seen as ugly by choric racist others in the film, a white woman elder is equally seen as ugly by others. Their combination as a couple is stared at by the camera in the film, forcing you to confront both of these judgements that frame the gaze of the film camera. Except the camera sees beauty too, as it is does in Franz Biberkopf / Fox, often more than in the bourgeois world of ugly second-hand furniture, and its dealers and businessmen. Moreover, however desolate Fox’s end, there remains an audience watching imagining alternative stories in a world reshaped.

Penman just before he defines Fassbinder’s quest as a ‘negative form of dandyism’ or narcissism, resulting in the man procuring ‘all the ways a body might find to make itself look worse: manifest ugliness, majestic dumpiness, cheap-looking clothes, sweaty ill-health’, he says that is because Fassbinder gave up being in order to be the ‘kind of being’ that is ‘being an image’ a ‘being on film’. The words used by Penman are almost childlike in their learned fat-shaming, don’t you think? And, in being so he misses all that is human in a Fassbinder film, which consists of embodied audience humanely assessing the ways and means by which innocent people come to grief in a politically crass system where everything is bought and sold, or if unsellable, thrown away as waste. The whole of my being responds like that watching Fassbinder, even the distinctly strange Querelle of Brest.

And Querelle of Brest is a film that Penman that defines Fassbinder negatively. , though he finds it deeply flawed and a film that doesn’t work with a male star, Brad Davis, whom he finds vapid. In section 188 of his book though he tries to have it both ways, describing the character Querelle as Jean Genet saw him as if Fassbinder attempted the same vision but then in a in a sentence beginning: ‘For Fassbinder, …’, reducing the filmmaker’s transcription to a rather thin boyish sex game with his own impossible doubling reflection.: ‘the handsome and easygoing youth, of everything he thought he never was and could never become’. It is all about the narcissism for Penman of a boy who never wanted to grow up in order to find himself for once desirable.

But he misses so much. For instance the twin brother whom he betrays and who is constantly referred to as a double, looks not a jot like Querelle in the film, and Querelle’s attraction to the hardened characters of Brest – the grotesquely muscular barman Nono and the pockmarked disappeared beauty of the Chief of Police – is something he suffers (brad shows it on his face), as in the scene of Nono’s anal taking of the handsome sailor in white in a back room of the bar. Fassbinder’s Querelle is not an icon of the excess of capitalist production: ‘low transactions. Everything bartered. Nothing learned’. The film like the book is an endless quest to find beauty in sexual landscapes (mirrored mainly the captain of the ship of men that includes Querelle docked in Brest’s harbour, where even the external architecture is brick towers made to look like penises but finding only violence. In one scene that has stuck with me graffito in a public toilet of a penis (scrawled on a transparent wall representing the cottage Querelle goes to is made to sheath the gun that the characters carry to up their masculinity and fearsomeness.

Hence I do not think Querelle is an avatar of what Fassbinder knew he couldn’t be. For like Franz Biberkopf you can become anything if you are in demand – commodities have that nature. Querelle is another version of the Ugly but in the commodity form of the beautiful, if a beauty that will fade in time. It is a fully achievable aim to be ‘ugly on the cover of Time’, for this is not just a reference to that magazine celebrating transitory fame in a shallow world but a recognition that beauty is just a surface but the surface of time (as it passes) has the power to make us all ugly, as well as famous, and still be the winner.

For me, Fassbinder took the notion of beauty and ugliness and cast them on that surface, contrasting how desire and its cousin commodification can transform perception of one to the other and back again depending on exchange values but never giving up on the beauty of the love we might aspired to. As Fassbinder aspired to it. Narcissists may take their own image as a lover, but even they know it is a poor substitute for a substance that exists somewhere, if not here in the world of alienated humanity, of buying and selling, where ‘each man kills the thing he loves’. And of mirrors that we love to hate and to love as they reflect the nature of our desires as fulfillable or an empty Gothic surface filled out with deliberately repulsive stone satisfaction only, as in the set of Querelle of Brest.

This blog was an experiment I won’t repeat.

All my love

Steven xxxxxxxx

[1] From the spoken text of Wizard of Babylon cited by Ian Penman (2023: 151) Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors, London, Fitzcarraldo Editions. Page numbers are those of the Kindle ed.

[2] Ibid: 106

[3] Ibid: 103

[4] Ibid: 107

[5] Chris Molnar (2023) ‘No Monuments: On Ian Penman’s “Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors” ‘ in The los Angeles Times (May 2, 2023) online: https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/no-monuments-on-ian-penmans-fassbinder-thousands-of-mirrors/ The quotation(another rhetorical question like those I cited is in Penman op.cit: 103.

[6] William Harris (2023) ‘Ian Penman’s Fassbinder Thousands of Mirrors Is a Love Letter to Postwar Counterculture’ in Jacobin online [5th Jan. 2023): https://jacobin.com/2023/05/ian-penman-rainer-werner-fassbinder-thousands-of-mirrors-postwar-counterculture

[7] Penman op.cit: 19-20

[8] Ibid: 151

[9] Ibid: 7f.

[10] Ibid: 163

[11] Ibid: 159f.

One thought on “‘I want to be ugly on the cover of Time’. This is a blog on narcissism in the queer art & politics of Rainer Werner Fassbinder as seen by Ian Penman (2023) ‘Fassbinder: Thousands of Mirrors’.”