BOOKER 2023: Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song may be a book that fuels opposing views of its quality. Melissa Harrison in The Guardian says it is: “powerful, claustrophobic and horribly real. From its opening pages it exerts a grim kind of grip; even when approached cautiously and read in short bursts it somehow lingers, its world leaking out from its pages like black ink into clear water”.[1] Max Lui in the i,on the other hand, says that though it is, “at least, melodious thanks to Lynch’s long sentences”, nevertheless “his pages are pocked with jarring word choices. Eilish thinks that a little boy’s skull is “wired” with red hair, she “sleeves” her raincoat on and walks into a cellar of “colding gloom”. This weird verbiage smacks of a stylist who is straining for effect”.[2] Can these critics be describing the same book? Let’s forgo silence and make this a time to speak about the defence of humanity against injustice.

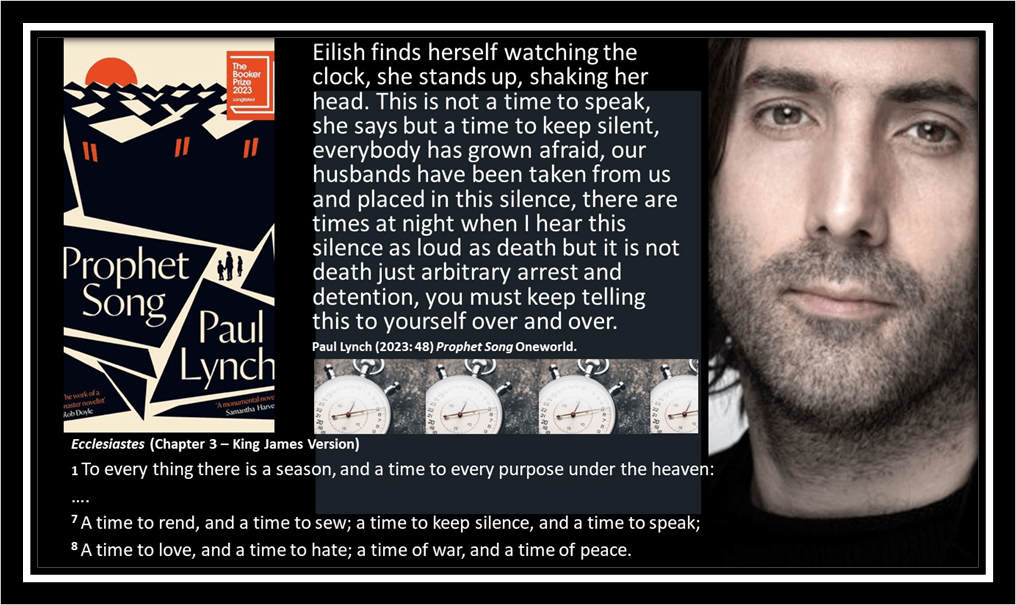

To speak of ‘good writing’ ought to be to speak of a multiplicity of options for writers aspiring to this description, yet views are often polarised between people who insists that ‘good witing’ is not only a standard to which to aspire but that it has norms and those who see it as aspiring to surprising micro-choices within its detail and innovative macro-choices in selecting its overall frameworks. Hence when Liu condemns some word choices as not only jarring but also analogous to pock marks on a diseased body, then we know he thinks the norms of good writing have been breached. Melissa Harrison, in contrast sees the effects of metaphor (in Lynch’s prose and her own) as rather a signalling of virtuoso power in the writing and a realism that captures ‘worlds’ that a reader may not have otherwise noticed but for the boldness of which boundaries Lynch allows his inky words to stain In truth I am with Harrison not Liu here and think this is writing of a high order. Indeed, Liu also says that the dystopian ideas of Lynch, ‘feel recycled and not at all prophetic’. But they are not, if so, recycled only from the short span of twentieth and twenty-first century dystopias but from a tradition of ethical writing and Scripture, hence my use in my collage above of the rather obvious echoes of that prophetic song, Ecclesiastes, in the Old Testament. However, this innovative writing comes at a cost for those who prefer the conventions of punctuated and ordered prose not to be breached. Harrison describes those breaches in Lynch accurately. (I have to say that though I know what Harrison means below, my resistance to the book’s methods never amounted to much, Though Geoff my husband found it did for him:

Prophet Song also features no paragraph breaks, so that blocks of text sometimes run on for pages, uninterrupted visually, until a gap appears for a new section: not only does dialogue lack speech marks but speakers are not given a new line. …

As a device this takes some getting used to, though it makes more sense as the book goes on and the claustrophobia builds. To begin with it acts as a barrier, as though one must fight one’s way into a book that is resisting being read.

However, turning from accurate critique to its opposite, it surprises me deeply that Liu can say what he says about the novel as ‘not at all prophetic’ and not refer to the fact that in a prominent place near the very end of the novel, Lynch gives a passage of towering rhetoric to redefine what is meant by the song of prophets throughout global history, and even otherwise insignificant local histories (had these localities in time and space not also had a poet to record their fate) to render them with the significance of both myth and the songs of poetry, and starting with the discoveries of a mother Eilish Stack about the superficiality of her notion that the message of history can only be that of terror and Apocalypse. To quote from Lynch’s sentences however is to defy conventions about beginnings and endings even in such micro structures – for who says that sentences should be micro structures and not able to capture the shifting of worlds in at least some of the domains in which we put trust in conventions.

… seeing that out of terror comes pity and out of pity comes love and out of love the world can be redeemed again, and she can see that the world does not end, that it is vanity to think that the world does not end, that it is vanity to think the world will end during your lifetime in some sudden event, that what ends your life and only your life, that what is sung by the prophets is but the same song sung across time, the coming of the sword, the world devoured by fire, the sun gone down in the earth at noon and world cast in darkness, the fury of some god incarnate in the mouth of the prophet raging at the wickedness that will be cast out of sight, and the prophet sings not of the end of the world but of what has been done and what will be done and what is being done to some and not others, that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end is always a local event, it comes to your country and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore, …[3]

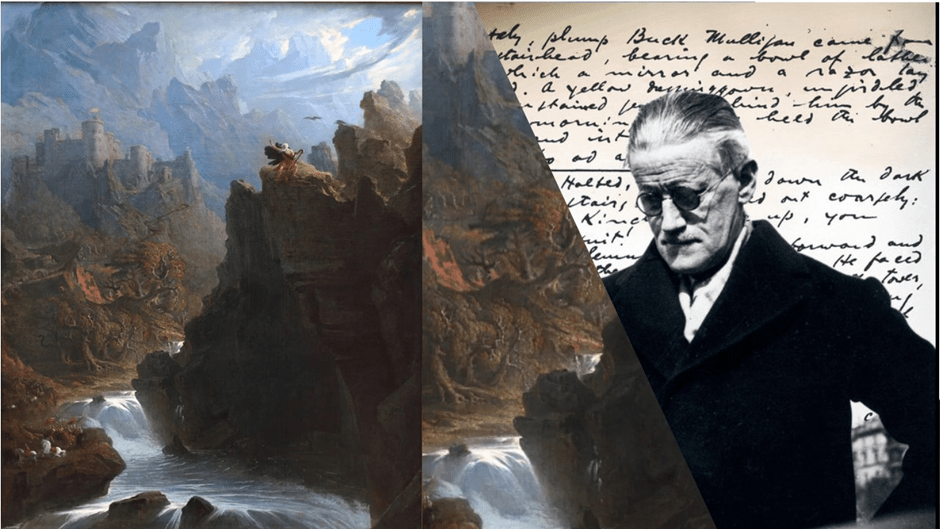

This is only part of the sentence in which it appears and the whole is reminiscent of the manner of the James Joyce of Ulysses, with perhaps just a taste of the mock-Gothic simulations of medieval bardic poetry in James MacPherson’s Verses of Ossian, as imagined by John Martin in The Bard, a favourite painting of mine in the Newcastle Laing Gallery.

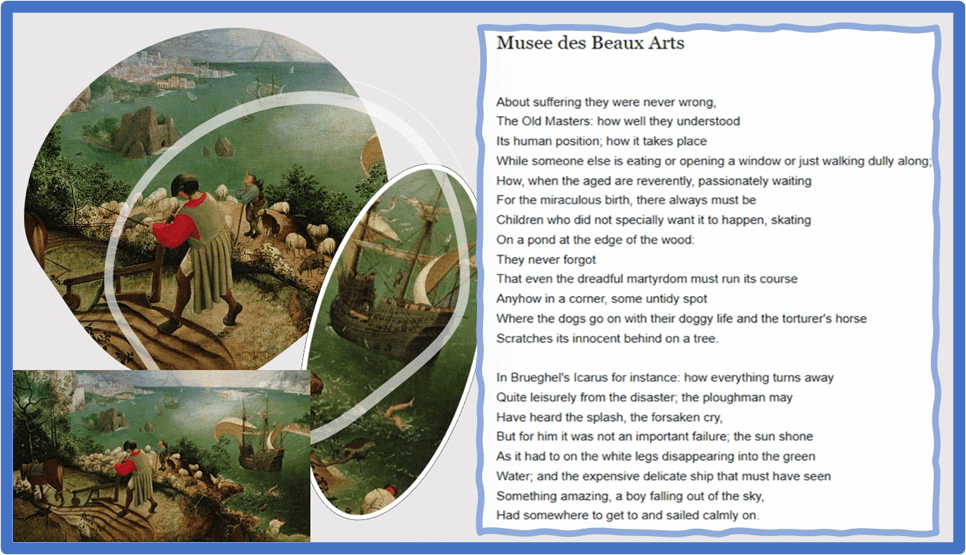

The passage blends mannerisms of oral traditional storytelling with an apparent stream of consciousness, whose disordered sequencing of thought serves to repattern writing into a new kind of order based around repetitive rhythms rather than merely phrases, and variations on a theme of ending, beginning, destruction and creation. It is not unlike Biblical verse then in its play on themes of eschatology and renewal, the closure offered by endings and the hope likewise promised by redemptive beginning. But also like the Martin picture, it insists on a local, though not as stereotyped as Martin’s Romantic chasm, somewhat after Coleridge, scene, for the whole point is NOT that the novel attempts to generalise dystopian eschatology, as Liu thinks in that lazy way where close reading goes by the wall, but to show that great tragedy is the more poignant in that it is not everyone’s tragedy. Auden too uses this theme in his poem Musée des Beaux Arts on Brueghel’s take on the Fall of Icarus.

Look again after reading at this sequence of Lynch’s sentence:

the prophet sings not of the end of the world but of what has been done and what will be done and what is being done to some and not others, that the world is always ending over and over again in one place but not another and that the end is always a local event, it comes to your country and knocks on the door of your house and becomes to others but some distant warning, a brief report on the news, an echo of events that has passed into folklore,

And if this is read with care, it tells us that, in modern terms, no-one ‘gives a flying f…k’ (to put it into the vernacular) about tragedy that can be distanced, intellectualised and seen as peculiar only to others (and in the worst instance of self-preservative thought) probably the sufferer’s own fault (social psychologists call this a ‘self-serving bias’).

Now this trait in it makes the novel rather different not only to anything Liu is reading but for me too. In fact by the end, I felt this novel fabulously innovative because it operated in so many different ways. Some people hate spoilers so if that applies to you skip the rest of the paragraph here – although my case is that knowing the ‘ending’ of this novel is not exactly a spoiler in the classic sense, because at its end the novel diverges into yet another kind of adventure line focused on both opportunity taking and risk – becomes in fact the beginning of an odyssey on sea channel migration and the role in this very contemporary tragedy for some – whom the comfortable at home in England (for it is England to which these boats are heading) can feel distantly sorry for, even blame as ‘putting their children and families at risk, or use as an example of the victims of evil traffickers in human misery without once seeing this tragedy as potentially theirs.

In that sense this marks a new novel starting at Prophet Song’s end: ‘she will never let go, and she says, to the sea, we must go to the sea, the sea is life’.[4] Of course, as we know, the sea is death as well as life for migrants but that is another story and fine – as long as it is someone else’s story. Likewise the rest of the novel the story pits an ‘ordinary if well-meaning left-of-centre family against the experiences of other nations – thus far at last – in incidents like fascist coups, populist right-wing government, political suppression, state surveillance and oppression, ‘disappearances’ of people thought to be activists, state control of young people, bloody civil war …. And so on and so on. Any yet Liu thinks this has all been done before. He needs a course not on reading but on self-serving bias. The stories of the novel are the suppressed counterfactuals of the story of achieved bourgeois stability that in the White West and North hemispheres has been introjected as the shape of human reality, except of course from those othered from that reality- the marginalised, oppressed and excluded, whom we know as objects of policy rather than as valid human subjectivities. Suddenly, in the course of this novel, Eilish Stack experiences that ‘othering’ and her life histories in the novel become the counterfactuals she once only read about in The Irish Times foreign pages.

But, having said all that (spoilers over if you have rejoined the reading) this is not what the novel essentially is, however important it is as a function the novel serves – a much needed one in our current and forthcoming politics. It is a novel however, in which he idea of ‘foreign’ or ‘alien’ nature of experience is constantly thrust on Eilish. Watching the scenes on TV of the peaceful march by teachers in which her husband, Larry, is arrested (later to be ‘disappeared’ and trying to contact Larry on his mobile phone when she attempts to leave her workday office, she ‘looks up and it seems as though the day has come to be under some foreign sky, feeing some sense of disintegration, the rain falling slow on her face’ (my italics).[5] As events escalate into greater political and family breakdown she gains the ‘sense now she is living in another country, this sense of chaos opening, calling them into its mouth’.[6] There is political reality, as well as the common sense of anomie in the depressed person in the way in which, when she drives with the weight upon her that her elder son Mark may join the rebel army against the fascist Irish government, that it ‘is some other version of herself she puts into the car’:

There is a breach, she can see this now, between things as they are and things as they should be, she is no longer who she was, no longer who she is supposed to be, Mark has become some other son, she is now some other mother, their true selves are nowhere – …[7]

The sense of alienation from her family and her role as ‘mother’, which all the assumptive characteristics that carries gives way to a similar feeling in her child, Molly: ‘It is as though she has become separate from them all, foreign almost, like some other child in some other house,…’.[8] Foreign, alien, and ‘other’ become words indicative not only of psychological distress but counterfactual history. An even clearer image of this emerges to swallow up all of Eilish’s vision of the streets of Dublin when the civil war reaches their own street: ‘this street that looks like two places at once as though some filmed transparency of a foreign war has been placed upon an image of the city, the summered colours fused with the ashen hues of destruction passing through in a rush’.[9] Perhaps the most beautiful of these effects of doubled vision – of a ‘known’ reality captured by an ‘alien’ new vision of what might be is the nearest to the prophetic and bardic in its language, is where Eilish imagines the long disappeared Larry, her husband and trade unionist: ‘How alien the world in the blue hour of dawn and yet it is known, the rain murmuring in the trees, it is an ancient rain that speaks to the place where it has always fallen, the cherry trees rooted in the earth, a strip of ribboned light for every week he is gone’.[10]

The novel to me, though it differs from any other Irish novel I have read, is fundamentally Irish precisely in that it understands that we can understand the passage of time and its experienced local (in different periods of time and tracts of geographical space) variations only in the sweeps of transitional states, where the nature of what is real is questioned. In the largest senses these are historical passages from order to disorder and vice-versa such as those of Civil War (raw memories in Ireland as in the early plays and novels of Sebastian Barry – Aeneas McNulty in particular – though Irish citizens are often asked to forget this as well as fantastic counterfactual projections in this book), but also of the passages involved between different stages of the process of growing up, between time experienced as sacred or ritual and as profane (the time of liturgy or the everyday time), the time too between sleep and waking. The latter transition is often evoked in the very language of the piece. Hence the importance to this text of the prophetic book, Ecclesiastes, especially chapter 3 thereof, with its evocation of time as the passage between competing and related binaries, so much so that they never remain binaries, but whose most famous moment is the passage between speech and silence. These themes, of course work together within this patterned novel.

In the quotation I use in my first collage in this blog Eilish and Carole, who have both lost husbands associated to mild and peaceful political resistance to the Fascist regime, puzzle openly together about the silence that met their joint disappearance. That silence is based on the fact that the certainty of their husbands’ death is worse than the mere fact of ‘arbitrary arrest and detention’. Hence, for Eilish at least this ‘is not a time to speak .. but a time to keep silent’, mirroring the wisdom of Ecclesiastes 3:7.[11] Eilish and Larry’ solicitor, Anne Devlin, attributes the ‘wall of silence’ to the agency of the new state police force but and generalises this silence as a ‘black hole opening before us’ that ‘will continue to grow so that it will consume this country for decades’. What I see here is a silence in the figure of an open mouth swallowing into its void, whilst able to utter nothing, the basis of all our expectations of public or private safety.[12] To speak is unsafe and hence the union minder, Michael Given, ‘makes a rueful shape with his mouth’ (perhaps the shape we saw above), for there are people listening to our talk we hear early in the novel. And we learn about this as if we had awoken from a dream of safety that is a lie. This is perhaps the first time that the transition between sleep and waking (echoing with the current obsession on the right with the political liberal as ‘woke’ is used in the novel:

Look at you lot, she said, the unions bowed and silent, … Something inchoate within her knowledge has spoken and she feels afraid, she can hear it now and speaks it silently to herself. All your life you’ve been asleep, all of us sleeping and now the great waking begins. This night-haunted feeling that won’t let her go, …[13]

Such great metaphors of political awakening, though often into the fear accompanying the knowledge of oppression is interwoven by episodes of transition for the characters between somatic sleep and its opposite, between which dreams are a kind of mediator. It applies even to hearing one’s children sleep whilst the external world grows rough, to those states wherein on waking we struggle to discern what is or who we see around us (when for instance DI John Stamp breaks her sleep (although sometimes he is merely a feature in a dream). An event in the novel itself may soon slip back into an explanatory metaphor of generalised feeling: ‘’this feeling as though a great sleep has broken. That they are dreamers awakened to the beginning of night’. Characters are captured ‘clung with shadow and sleep’, experience trauma that is neither one nor the other – sleep nor waking ands is experienced as neither fully voiced and speaking nor silent.[14] As an example of how a time for sleep and a time for waking (to mangle Ecclesiastes) also becomes a ‘time to keep silent, and a time to speak’ from that great prophetic song, there could not be a better one than this, for it shows the binaries losing their sense and becoming themselves muddled as experiences. The speaker is Carole Sexton, another woman whose husband is disappeared:

I don’t sleep much at all, she says, I dream each night of a soundless sleep but that is impossible now, it took me some time before I understood that I was already asleep in a manner, you know that I was sleeping all the time I thought I was awake, trying to see into this silence consuming every moment of my life. I thought I’d go mad looking into it but then I awoke and began to see what they were doing to us, the brilliance of the act, they take something from you and replace it with silence and you’re confronted by that silence every waking moment and cannot live, you cease to be yourself and become a thing before this silence, a thing waiting for the silence to end, a thing on your knees begging and whispering to it all night and day, a thing waiting for what was taken to be returned and only then can you resume your life, but the silence doesn’t end, you see, they leave open the possibility that what you want will be returned some day and so you remain reduced, paralysed, dull as an old knife, and the silence does not end because the silence is the source of their power, that is its secret meaning.[15]

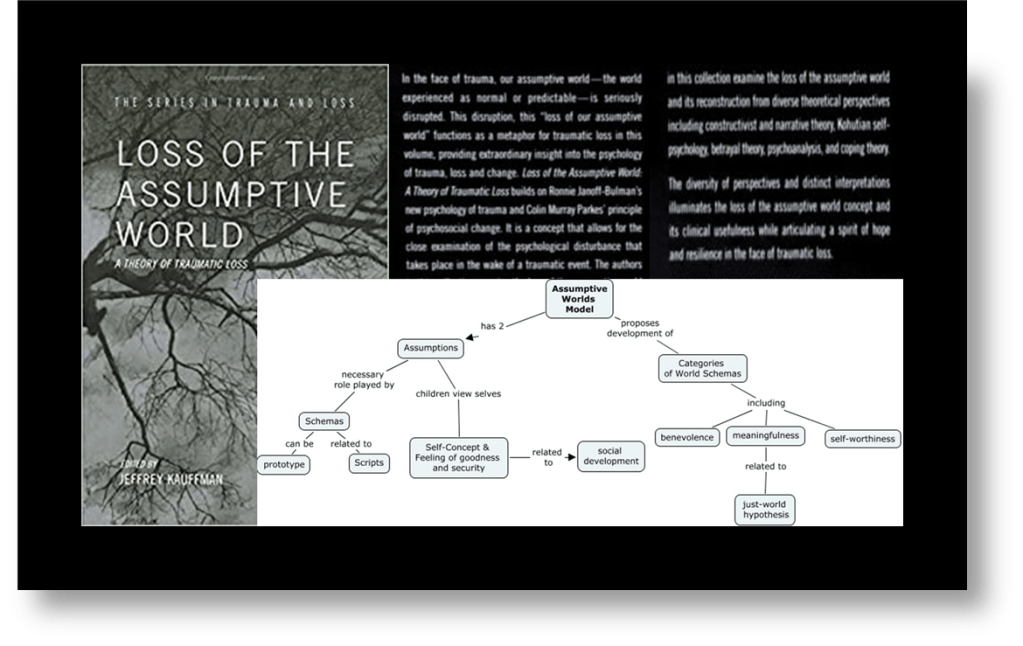

A characteristic sentence this, it works with repetitious patterning that queers the binary contrasts it appears to work with so that sleep is waking, and silence is noisy – very. And then the secret – the issue is the maintenance of power not just through aggression and oppression but by the engineering of a deep uncertainty. No-one, at this point, could mistake that the apocalypse that is the burden of the story is an allegory of our present state of collusion with the political enforcement of a status quo that only pretends to normality, let alone to benevolence. Eoghan Smith in a good review in Literary Review says that what this is ‘a masterly novel that reminds us that democracy is fragile, and that it is fragile now’ (my italics).[16] But it is not only democracy that is fragile it is the assumptive world built within ourselves that refuses to see the dangers, except in extremities, such as this novel has to describe, which will make us realise that if we are awake and if we speak out, that the world and the self are both like an attic to a house we feel is ordered and tidied that contains what we do ‘not want to see’:

This feeling the attic does not belong to the house but exists in its own right, an anteroom of shadow and disorder as though the place were the house of memory itself. … lost in the disarray of vanished and forgotten other selves, …’.[17]

People invoke Cormac McCarthy with regard to passages like this, but whatever the fineness of such judgement, the point remains that apocalypse is not a future dystopia but has already occurred, if only we dare look long enough at the way we tidy up our lives and national politics from signs of its true disorder. Hence the Gothic feel of the writing, the haunting by ghosts of the ‘dead’ and ‘disappeared’ (often hard to distinguish), the derangement of characters around strange beliefs and visions – such as the ‘worm that turned’ that obsesses young Bailey, and which perhaps turns out to be the excremental vision that shows that recreation and re-creation are based on accepting that we work to renew from s…t or from nothing at all: ‘the fallow field, the dead field crowned with weeds and underneath the worms turning the soil and within the soil the remains of the last crop. Dead matter decomposing to give nutrient to what grows next, …’.[18] It is a space where war can seem beautiful.[19] And the base debate in the novel is that between ‘lies’ and reality, fact and fiction, a debate often hanging around metaphoric use of mirrors, as in literature from the very beginning, but here surely echoing T.S. Eliot’s The Four Quartets. Again the tone is Ossianic:

The real is always before you but you do not see, perhaps this is not even a choice, to see the real would be to deepen reality to a depth in which you could not live, if only you could wake up ——-[20]

We can, if you like, see the project around politics and the rise of the fascist National Alliance Party (NAP) in the novel. Simon, Ailish’s father, whose dementia increases throughout the progression of the story, says early in it something like that: that the NAP ‘is trying to change what you and I call reality, they want to muddy it like water. If you say one thing is another thing and you say it enough times, then it must be so, and if you keep saying it over and over people accept it as true’.[21] Of course that is true of current political strategies: think of Donald Trump and Boris Johnson. But reality is perhaps more malleable anyway than we think to a range of forces; from those internal to the body, to the ideologies of the diurnal common lives of us all AND those of harder core politics to the external forces of censorship, propaganda and oppressive use of detention and state execution. But they cannot be separated I would say. Hence this novel is not a poorly written political dystopia as Liu wants to convince us but truly a ‘prophet song’, a way of asking us to take charge of the kinds of world we allow to come into beginning when we contemplate changes of all kinds. Mothers like Eilish often know this, as in this fine perception of how Ben and Bailey, very different sons, relate to their father, Larry. Eilish hopes Ben will ‘measure up to his father’, but, as she knows ‘all boys grow up and pull away from home to unmake the world in the guise of making it, nature decrees it is so’.[22] Notice that. We aspire to our fathers and to the past by pretending to re-make their world as kit was but have the capacity to ‘unmake it’ and perhaps, though the option isn’t mentioned here, ‘remake’ it in a better (or worse) form. It is a lesson as old as Oedipus‘ relationship to his rebellious sons, or Gloucester, in King Lear, to his.

I love the novel.

Steve

[1] Melissa Harrison (2023) ‘Prophet Song by Paul Lynch review – Ireland under fascism’ in The Guardian [Thu 31 Aug 2023 07.30 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/aug/31/prophet-song-by-paul-lynch-review-ireland-under-fascism

[2] Max Liu (2023) ‘Prophet Song by Paul Lynch, review: I’d be surprised if this won the Booker’ in The i [August 24, 2023 11:00 am(Updated 6:21 pm)] Available at: https://inews.co.uk/culture/books/prophet-song-by-paul-lynch-review-id-be-surprised-if-this-won-the-booker-2556679

[3] Paul Lynch (2023: 304) Prophet Song Dublin, Oneworld Books.

[4] Ibid: 309

[5] Ibid: 31

[6] Ibid: 36

[7] Ibid: 110

[8] Ibid: 168

[9] Ibid: 204f.

[10] Ibid: 214

[11] Ibid: 48

[12] Ibid: 152

[13] Ibid: 38

[14] Ibid: 41, 64f, 101f. 111, 133, 140,192 (Stamp in a dream), 214.

[15] Ibid: 165f.

[16] Eoghan Smith (2023: 53) ‘An Inspector Calls’ in Literary Review (Issue 522, September 2023). 53.

[17] Paul Lynch, op.cit: 176

[18] Ibid: 281 (or Bailey’s worm see ibid: 154f, 192 for instance).

[19] Ibid: 167

[20] Ibid: 193

[21] Ibid 20

[22] Ibid: 25

Beautiful post

LikeLike