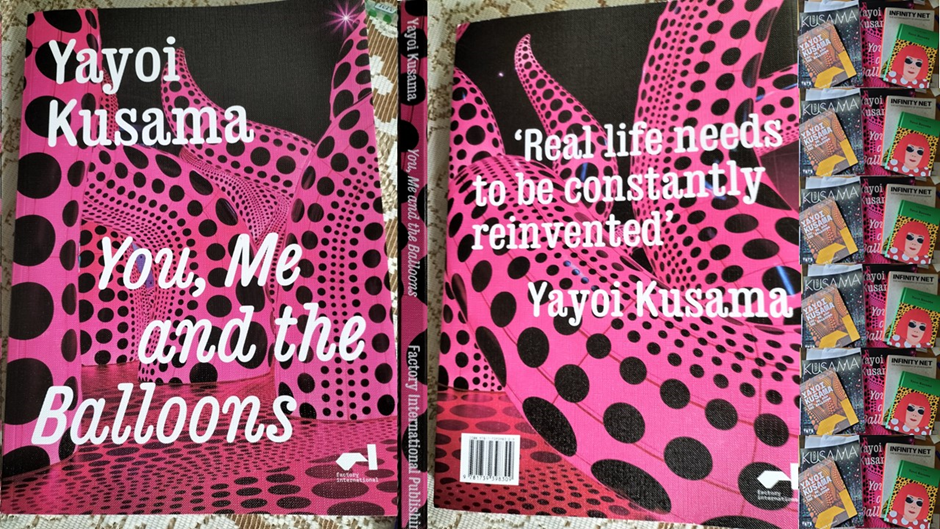

This blog is the final ONE on Yayoi Kusama and relates to the catalogue of the exhibition at Factory International Manchester Aviva Studios, which I visited on Tuesday 4th July at 11.15 a.m., as part of a selection of the items from the Manchester International Festival. The catalogue is beautiful and the photography stunning but this piece concentrates on a typescript conversation between Philippa Perry, psychotherapist, writer and artist and Anil Seth, a neuroscientist interested in the nature of perceptual experience of the self and the world’, in brief ‘the brain basis of human consciousness’.[1] The conversation appears in: Phoebe Greenwood (ed 2023.) Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons Manchester, Manchester International Festival, 57 – 81.

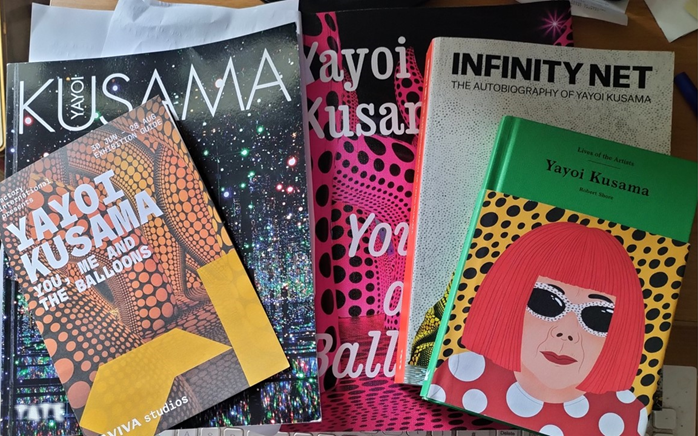

The expanded Kusama books at home and a close visual of the new catalogue: my photographs collaged.

I have completed two earlier blogs related to this exhibition. One a critical preview based on preparatory reading, the second a description of my ‘trip to the exhibition’ itself. The links will take you to these blogs if you so desire to be taken.

In the first of the two blogs I mention above I instance an internal debate in an earlier book on Kusama between feminist psychotherapist Juliet Mitchell and the view that ‘a psychoanalytic understanding alone of such images cannot account’ for her work. Mignon Nixon expresses that second view:

Kusama’s recourse to ‘compulsive repetition’ is a symptom of trauma, critics have argued, with some encouragement of the artist herself. … But it is clear that Kusama’s art was conceived in rebellion against repression in every form: “my parents, the house, the land, the shackles, the conventions, the prejudice. What is traumatic in her art is its reflexive reiteration of that position, its continual protest against external control, which became intolerable in any measure precisely because of its overwhelming effects in the past’.[2]

I tend to agree with Nixon, though I suspect so might Juliet Mitchell have agreed, if asked to respond, of which in that book (a Tate publication) there is no evidence of having happened. One of the intellectual beauties of the beautiful looking catalogue from the Manchester International Festival is that so many of the contributory pieces are dialogues rather than monologues, when they are not largely descriptive of the art or its base concepts (though these are immensely useful too, especially the ‘You, Me and the Balloons Lexicon’ (pages 27 – 32)). However one dialogue is really an updated one from an earlier Paris exhibition (that by Seungduk Kim and Franck Gautherot – pages 33 – 43). The discussion between Philippa Perry and Anil Seth is novel though and addresses itself to the current moment in Kusama’s career and this exhibition, though very far from exclusively. Indeed to do the latter would be a bigger mistake in an artist of Kusama’s global significance.

Philippa Perry (UCL photograph) and Anil Seth (Faber & Faber photograph).

I concentrate here on this piece for it takes the debate I point to in the Mignon Nixon quotation above further and with less combative style. The conversation in this book has an openness to the fact that any politics of liberation (one that stands against repression as Mignon Nixon says Kusama’s does) has to be open and perhaps to stand against the notion that only expert academic voices are worthy to comment on art, even in relation to the capacity of art to understand the psychology of everyday life or trauma. Anil Seth speaks of the ‘immediate appeal’ (elsewhere he also calls it a ‘broad appeal’) of Kusama’s work and of not needing to ‘go in’ to any exhibition of her work ‘with a perspective or with a whole heap of background knowledge’. In fact, he continues, that appeal is broad ‘because she is externalising her way of encountering the world, which implicitly, without even thinking about it or knowing anything about it, can make sense to each of us, because we will take that in our own direction’.[3] Our reaction indeed to the work may be purely related to its aesthetic beauty (or just beauty and forget the term aesthetic) or being ‘awestruck’ with wonder, as Perry says often, and maybe (as Seth says) some viewers will just ‘have fun being taken out of normal daily life’ (indeed I encountered very visible versions of that reaction on our visit).[4]

But, of course you don’t get two leading experts in their wide fields to comment on art for nothing, and at the heart of this discussion (never ever polarised as you will see on any reading) is the issue of whether Kusama speaks to us from the seat of her own embodied trauma or from a less charged psychological point of view. The latter starts from the neurodivergences that cause variation in how everyone perceives the world. Neither speaker takes one side or the other, though Perry may raise the issue of psychological trauma more than Seth and relate it to both Kusama’s biography and life-course up to her voluntary residence in a psychiatric institution in Japan. The nearest we get to such difference is when Perry stresses the independence of the term UNCONSCIOUS (as used in psychotherapy and psychoanalysis) 0f the SUBCONSCIOUS (as Freud did), and the access of the former to the fantastic. Perry says she is ‘all about the fantasy and art of psychotherapy, rather than the science of anything’. Seth, in contrast, uses the words ‘unconscious’ only semi-independently of consciousness, stressing shared aspects of their functioning, ‘where unconscious processing is not a separate little mini-mind’ but ‘is the infrastructure that underpins all our conscious experiences. We can perceive unconsciously. We might have unconscious beliefs as well’.[5]

Both Perry and Seth though have an interest in externally prompted experiences of psychodelia and those of people born with access to psychedelic experience, based on their neurodivergence.[6] There is a similar interest expressed in synaesthesia, which Seth shows is not confined to those born with the capacity but is also experimentally reproducible (or entrained), though it is not an enduring trait as a result.[7]

More interesting and fruitful consensus is found in relation to the fact that both of their perspectives are at work implicitly, at least, within responses to Kusama’s work. If there is individual pathology pressing on Kusama’s experience from her traumatic past in her work, this has to be seen also in terms of Kusama’s ability to model embodied perceptual processes that everyone shares, with or without traumatic shaping of some experiences. Perry understands Kusama’s ‘uniqueness’ (a word proffered by Seth) as in part a product of experiences like, for instance, being sent by her mother to ‘spy on her father having sex’ with other women, and, for another example, not having ‘feelings and need’ (and even her perceptions which are treated as merely hallucinatory and delusional) ‘accepted or validated’.[8] Seth, in nuanced contrast, argues that Kusama is ALSO showing, in reproducing her sensed world as art, ‘what brains tend to do’ when they attempt to make sense of the world and self. He embraces truths that spring from ‘both of our perspectives, whether it’s at the level of a narrative or life story or the more basic level of how the brain makes sense of the here and now’. Indeed both of these perspectives in Seth’s account use similar tools – stories:

The light that is coming into our eyes, for example: the brain has to make sense of it, in order to generate a visual perception. The brain is always telling a story to itself, and it’s that story we experience, not the sensory signals that guide the story.

He doubts (because he also doubts the factual nature of unconscious operations that do not work through consciousness, except (as in Freud) as a filter) that Kusama’s ‘hallucinations’ (such as a world overlaid by polka dots) were caused by trauma: it is ‘a priori a bit unlikely’ he says that ‘visual perception’ at a basic biological level could be so affected and that a ‘neurobiological cause’ was the more probable. Yet his summary is beautiful, giving and consensual:

… it also could be that there is both a neurobiological cause for her hallucinations, and an overall self-related response to trauma, which happened independently but came to interact in the same person – Kusama – and that it is this interaction that may be key to her creativity, her art. [9]

He sees some of this causation related to neurodivergences that explain how phenomena like after-images of objects seen – but then turned away from – persist for different durations in different people.[10] No doubt not everyone finds this as fascinating as I do, because I need to blend my interests in mental health, psychology, neurobiology and the arts in all that I find exciting and fruitful in somatic-affect-driven-intellectual lives. For Seth makes it clear, as he must, that neurobiology still does not have all the answers, even if these answers would never be the same as those of psychotherapy. However, it matters that he insists that ‘the self’ and ‘the world’ (as we sense them) are interactive causes and products of perceptual processes and that its sources are not those we use to call (after Gibson) ‘direct perception’ supplemented by merely mental brain processes. For the body and its affects are also consulted. At root looking at Kusama’s art raises:

.. the question of how the brain interprets the sensory information that comes in through the eyes and the ears and up through the body into the brain, from the internal organs too, to drive conscious experience filled with objects and people and spaces and colours and shapes and feelings. There is something going on there that transforms signals into worlds: how does that happen?[11]

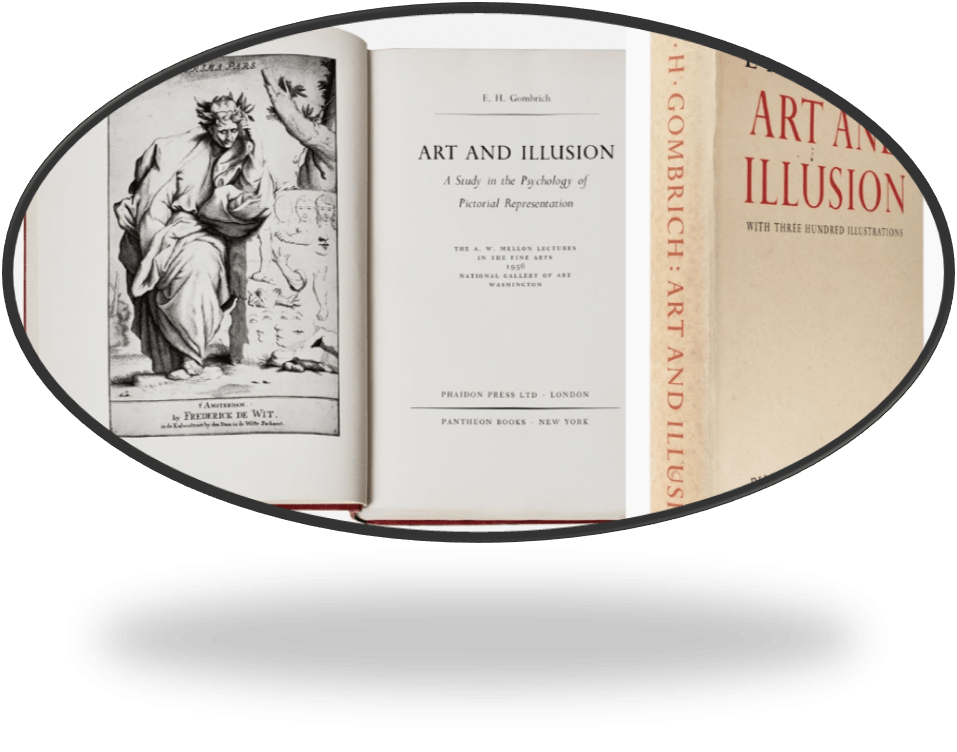

When both speak of art they agree it is neither an object nor a subjective avatar of what is thought to be seen located in the viewer’s subjectivity. Instead: ‘It happens in the middle where we meet’ (the art object and the viewing subject, that is). To gain art historical credence for this belief, they both agree on the theory propounded by Ernst Gombrich that in the making of any perceived art there is a ‘beholder’s share’.[12]

No art is completed until the beholder finds it so in their perception and thereby effect its changing forms through space and time. However, more important to me, especially in thinking back to my fondness for Mignon Nixon’s take on Kusama, is how both conversationalists find special meaning in Kusama’s art that generates perception, and possibly, action at the level of politics and metaphysics (in terms of what it means to be and know things).[13] Both seem to agree with the following two quotations (from Seth) with which I would like to end this reflective blog. For art that is not politically generative is, in my eyes, false art. But first an explanation. It is easy to read in what follows a plea for consensus around difference (that must also include the oppresser), but such a reading flies in the face of the kind of politics, of which both conversationalists are aware was and continues to be the politics of Kusama. For if she wants to bring people together, it is not in support of the status quo, but in order to change it in the name of love and justice. But, of course, Seth does not spell out that the point of artists, like philosophers (to mangle Karl Marx), is not to ‘interpret the world but change it’.

If you want to bring people together, the first thing to do is to encourage a recognition of how we all differ in the first place, to cultivate a kind of humility about each of our distinctive ways of seeing and believing. [14]

The idea is to encourage us to challenge the perceptual habits we fall into. And when you challenge our everyday ways of encountering the world and the self, you open up the potential for all sorts of other changes that will depend much more directly on the social context of the day.[15] (my italics)

Do remember that it is a beautiful book whether the essay appeals to you or not. It costs of course – good reproductions do – but I felt it worth it.

All my love

Steve

[1]Seth quoted in Philippa Perry & Anil Seth (2023: 57) ‘Stood in a Field, Studying the Human Heart: A discussion’ in Phoebe Greenwood (ed.) Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons Manchester, Manchester International Festiva, 57 – 81.

[2] Mignon Nixon (2012, reprinted 2021:181) ‘Infinity Politics’ in Frances Morris (ed.) Yayoi Kusama London, Tate Publishing, 176-185..

[3] Anil Seth, op.cit: 72f.

[4] Ibid: 57, 74 (column 1 and 2) respectively.

[5] Ibid: 67

[6] Ibid: 79

[7] Ibid: 73

[8] Ibid: 59

[9] Ibid: 60

[10] Ibid: 61

[11] Ibid: 57

[12] Ibid: 69

[13] Ibid: 75

[14] Ibid: 75 – 78 (there is a double page photograph intervening)

[15] Ibid: 79

2 thoughts on “This blog is the final ONE on Yayoi Kusama. The catalogue is beautiful, one essay is fascinating: Phoebe Greenwood (ed. 2023.) ‘Yayoi Kusama: You, Me and the Balloons’.”