Art about itself: artistic making in Hoffman’s The Sandman and sculpted scopophilia in Léo Delibes Coppélia. A review of the BBC production (on DVD) of the ballet restaged from an earlier production by Anthony Dowell. This blog acts as my preview of seeing a live performance by the English Youth Ballet in Sunderland in September.

For this year’s English Youth Ballet Coppélia tickets: https://www.atgtickets.com/shows/english-youth-ballet-coppelia/sunderland-empire/

UPDATE: Well the Sunderland Empire production came but Justin had dumped me and Geoff by then and all association with us, and it turned out to be a damp squib, so I am pleased for him he missed that. It had all the trappings of decent set and middling costumery but NO live orchestra – one in the eye for Delibes that. Moreover though the principals were good – Swanilda excellent in fact – the performances lacked character beyond accuracy. But worst of all the production used an under-rehearsed and over young (some appeared to be 5-6 years old) children in the corps de ballet. The performances therefore lacked everything that makes this ballet beautiful and that extra that made it other than an a fairy-tale and a serious piece of art in performance. The issues around youth, age and sexuality were not even near the surface, though the storytelling was good mainly because of the use of a mature mime artist in casting Coppélius. We left after Act 2. See the brief blog at this link (https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2023/09/02/how-do-you-integrate-the-aim-of-child-education-in-an-elite-art-like-ballet-with-public-production/).

THE ORIGINAL PREVIEW STARTS HERE:

We are all clear, aren’t we, that to translate a story between media involves something well beyond accurate transcription? Any particular artform will demand metamorphosis of elements of plot, character and medium of such scale that other metamorphoses might well seem not only allowable but necessary to be facilitated. What a later artwork owes to an earlier one then is usually either highly contested; requiring sharp discriminations between the media involved in each or considered irrelevant. Very few productions of ballets spend long on originals of the story, for ballet has its own traditions. Let us take the ballet, originally choreographed in 1870 by Arthur Saint-Léon to music by Léo Delibes, and libretto by Charles-Louis-Étienne Nuitter. Nuitter himself believed that his version was based on E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s Gothic short story Der Sandmann (The Sandman).

Self-portrait, and sample signature, Ernst Theodor Wilhelm (penname ‘E.T.A.’) Hoffmann, (1776 – 1822), Jurist, author, composer, music critic, artist, Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E._T._A._Hoffmann & realisations of Der Sandmann as graphic novels available at: https://comicgate.de/rezensionen/sandmann/

This Hoffman story was first published in 1817 in Die Nachtstücke (The Night Pieces). The story in this tale has many more strands than the ballet and complements Hoffman’s usual Gothic fare concocted from stories of doppelgängers, madness, death, and alchemical magic often in the guise of science with strange pseudo-resurrections into life. Hoffman’s characters have different names and their lives are pursued in a longer duration of time than in the ballet. Moreover, the identity of the Sandman is often problematic, appearing only in the consciousness sometimes of a decidedly unstable narrator both as boy and man, Nathaniel. We see this because his control of the story, first told in letters, is often passed to saner narrators – particularly a very enlightened and educated woman (his fiancé), Clara, who explains Nathaniel’s feared figures as illusory representations of ‘dark forces and compulsions’ within Nathaniel himself.[1]

We might have guessed that anyway from the tone of Nathaniel’s prose (even in English translation). The Sandman itself starts off as a ‘fantastic monster of the kind children fear so intensely’ but in fact turns out to be an old and, to a child, physically distorted barrister friend of his father’s, Coppelius, his colleague in amateur science.[2] But the Sandman takes different shapes and names during Nathaniel’s career and European travels. In one he appears as a seller of barometers, Giuseppe Coppola, to be displaced on another occasion as actually a man of the same name BUT a seller of optical instruments. Later still this same figure is perhaps that one fantasised as a purveyor of eyes from the heads of his victims designed to offer special qualities of magical vision.[3] Nathaniel doubts himself, of course– he even considers Clara’s view that his imagination has become overheated, to be the case. This places him (though he would not know that) squarely into membership of the group of Romantic unreliable narrators since Goethe’s Young Werther. He has, therefore:

… to admit to himself that the terrible spook was a figment of his own imagination, and that Coppola was an altogether honest craftsman and lens grinder and could not possible be Coppelius’ cursed doppelgänger and shadow-figure.[4]

However, even when (almost as if cleared out by some psychoanalytic trick of Clara’s) Coppelius – disambiguated from Coppola – disappears, the Sandman returns. However, the role of dark mentor passes to a Piedmontese Physics professor named Spalanzani (but not the real biologist of that name) who looks like the evil genius Cagliostro. We should note that the obfuscation of the identity of persons indicated here is typical of this piece. Where Nathaniel’s story in some small way matches that of Franz in the Delibes ballet is that the Italian physics professor appears, like Coppélius in the ballet (story to come), to have a daughter, but here named Olympia, whose ‘eyes had something glassy about them – I’d almost be inclined to say they could not see; it seemed to me as if she slept with open eyes’.[5] This is the first clue in Hoffman’s story that Olympia is in fact a mechanical doll. Another clue to the ballet’s influence by this story, and perhaps its deeper significance (for I think it has one despite the rush of all commentators to call it an ‘enchanting’ comic ballet (which it also is), lies in the fact that Nathaniel appears somewhat immune to what makes a woman beautiful other than external charms and which only others really see in Clara. ‘Clara could by no means have been considered beautiful: …’ insists Nathaniel though he also admits that people ‘who claimed to know a thing or two about beauty’ found her beautiful and that painters loved ‘her Magdalene hair’, one ‘fantast’ comparing her ‘eyes to a Ruisdael lake’.[6]

In the ballet, Franz too fails to acknowledge in Act 1 the commanding beauty and marriageability of Swanilda (Clara’s replacement in the story of the ballet). Instead, he sees beauty in many women, of whom Coppélia (another mechanical doll) is just one. But we need to look at that passage of Hoffman carefully because in Hoffman, Nathaniel is not only deluded by compulsive fears but by an inability to see how beauty is constituted in art (whether in Ruisdael or painterly models of the Magdalene) which he sees like and Neoclassicist theorist as entirely a different from a living breathing woman. No wonder then that impressions ‘of Olympia’s lovely figure hung everywhere he looked’ and that Clara’s image is ‘totally erased from his heart’.[7] However, the secret of The Sandman is that there is an answer to the question asked of Nathaniel by friend Siegmund (sic.): “tell me how in heaven’s name an intelligent man like you ever fell for the wax face of a wooden doll?’

And that answer lies in the preference for social and aesthetic, and book-based (academic), regulation of the definitions of the art-object and art’s boundaries (the imago rather than the living form). The contestation of that view is, of course, the meaning of Romanticism since Goethe (and his Faust in particular). Indeed Siegmund himself admits that most men find Olympia beautiful but for her vacant eyes and a step so “strangely measured, every movement seems prescribed by clockwork gears and cogs”. [8] And there we have it – the germ of a ballet, as I will go on to elaborate. But we need to think what exactly Hoffman says here. It is not that many men in positions of power prefer art over nature and the natural but that they prefer something lifelessly regulated (as clockwork is) to beauty that really lives and moves (itself or us) as natural life does or should do. Most modern men, Romantics think, prefer bad art that is the double of their own drained social life – a simulacrum of human relations. I would suggest that is a regulated conventional society aiming to subdue the danger of real warm breathing relations. Hoffman even plays a game here – for his work has comedy certainly. Instead of understanding that men ought to give themselves up to real feeling, even when it comes from a living breathing woman who loves them, they instead go further into ‘distrust of human figures’, for that distrust:

… seeped into their souls, In order to be completely convinced that they were not in love with a wooden doll, quite a few lovers demanded that their beloved sing something off-key and dance out of step, that they embroider and knit while being read to, play with Bowser, etc., and above all … occasionally say something in such a way as to demonstrate that their word necessarily derive from actual thought and feeling.[9]

This wittily ironic passage takes aim at bourgeois men in the guise of ‘lovers’, who want from their women a little bit of irregularity and imperfection as evidence of humanity, even the same breaking of socio-linguistic rules that Romantic poets were insisting to be necessary to make living poetry. But the irony in this is that these ‘lovers’ are figures of fun. Their solution to uncovering counterfeit women is as clockwork and rule-driven as had put them at risk of adoring a doll rather than a living person in the first place.

Osbert Lancaster’s fairy-tale village sets, which are described as ‘right for the story’ as if it should not be taken any more seriously than a domestic folk-tale.

We cannot know if the partnership of Saint-Léon, Delibes and Nuitter read Hoffman in this way, but it is likely. However, we cannot either treat any production as focused on any intention of any of those originating sources. Moreover it is common to hear this ballet spoken of as, using the example of Deborah Bull introducing the BBC 2000 video, a ‘whimsical tale’, at once ‘light-hearted’ and based in a fantasy setting – a ‘non-specific mid-European state’, associated with ‘ballet land’ in the mind of ballet-goers. This is emphasised even more by Osbert Lancaster’s fairy-tale village sets, which are described as ‘right for the story’ as if it should not be taken any more seriously than a domestic folk-tale. The point that ballet has its own constraining conventions is brilliantly made By Sarah Crompton, speaking of the production on which the DVD version I watched was based but, being a year earlier, with different performers:

Dance has a strange relationship with its past. No art form looks back more, fretting away at keeping the detail of past performances alive. Yet in no other sphere is it so difficult to preserve exactly what a creator intended: styles and tastes change, steps get forgotten, embellishments are added. / … take the Royal Ballet’s production of Coppélia, first danced at the Paris Opera in 1870, which arrived in Britain in 1933 in a version that had been reimagined by Lev Ivanov and Enrico Cecchetti, brought from Russia by Nicholas Sergeyev and then restaged by the company’s founder, Ninette de Valois, in 1940.[10]

In a deep way then ballet is continually recreating traditions which it may be unable to maintain and in some more creatively innovative, or even less imaginative, hands, may not wish so to do. Its first allegiance is to the tradition of the art of a ballet company and its ingrained ways of working sometimes, methods sometimes seen as over-regulated by modern dance companies. In particular, the latter may not wish to preserve the hierarchies of the ballet, which allots roles according to positions achieved in the company based on assessments by company directors. I spoke about this in relation to the Birmingham Royal Ballet Swan Lake and a reminder where I said, possibly overstating the case, which will explain my collage illustration preceding it which shows the hierarchy as I visually described it for the Swan Lake blog (the complete blog is available at this link):

The potted history of the ballet in the programme showed it to be a form, when Tchaikovsky himself ventured into it to ‘try [his] hand at this kind of music’; subservient to the aesthetic whims of potentially ‘indifferent’ choreographers all too ready to serve the egos of ‘star’ performers for a more commanding role, even at the cost of harder work for those ‘stars’, or so says Noël Goodwin in this rather good short essay in the programme. … After all, the Petipa-Ivanov original choreography (still used as the ballet’s basis) had highlighted the role of the star performer playing both Odette (the white swan/princess) and Odile (the black swan/princess and an apparent simulacrum of Odette) by inserting 32 fouettés (turns on one leg propelled by the extended raised leg – almost Herculean in muscular difficulty no doubt) into the story in Act III for its chief female star.

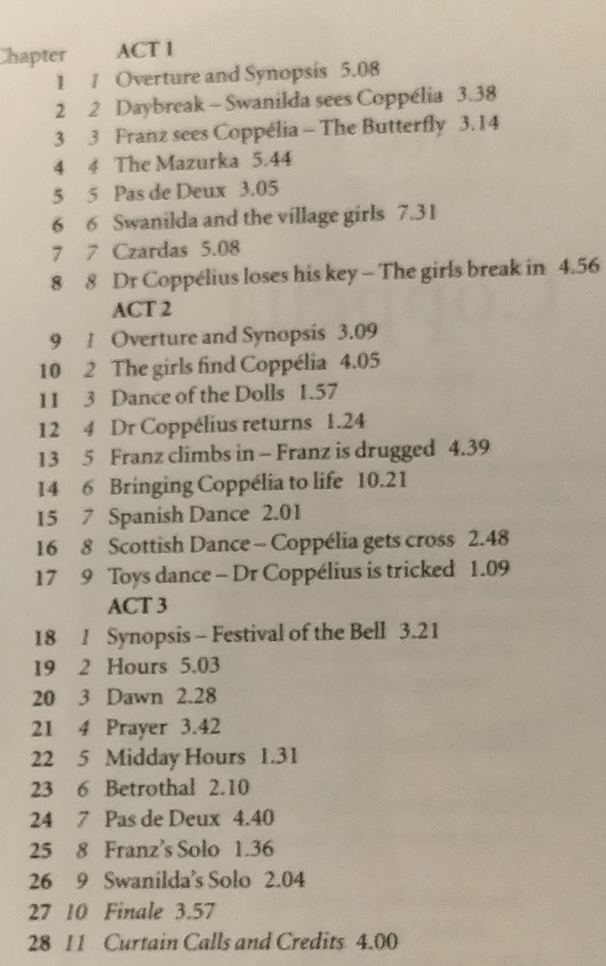

There is no doubt that such histories would have lain behind the production history of Coppélia too, for this is a ballet marked by star performance after star performance. Take this schedule of the libretto chapters of the performance I am using to preview the ballet here in which so often in the action in Act 1 or 2, where there is more story to actually tell than in Act 3, falls into excerpts entirely made up for the Principal Dancers to show their wares in solo or in a pas de deux. There are scenes for the corps de ballet certainly that are quite magnificent, if not of the dynamism of the Swans in Swan Lake, for instance the Czardas that end Act 1, but for one important piece of action linking Act 1 to 2. Set piece dances are known for the corps which most often set the theme, rather than the scene, like the ones relating to the passage of time (Hours, Dawn, Prayer, Midday Hours) in Act 3, with solo, pas de deux or national dance type raising exception of exceptional individual skill in a received dance form.

Often the corps de ballet is used to define and extend vertically, by an ensemble of raised limbs, the space to be filled by Principals to show their wares and to be applauded for this each time; an applause prompted by the corps acting as a kind of avatar of how the audience should react. In the piece below the Burgomaster (in green) who sits at the inn door on the left side of the stage in order to be entertained. It is he who has set up the show of celebration before and after the village’s communal marriage ceremonies (with financial prompts too from him for his people) and who will endorse for the audience the expected worthiness of the corps de ballet and, especially, the Principal Dancers. The issue is, as in Swan Lake, that these dances are to be judged for their excellence.

‘Often the corps is used to define and extend vertically, by an ensemble of raised limbs, the space to be filled by Principals to show their wares and to be applauded for this each time.’

It is here then that we will find equivalence in terms of how balletic art is conceived of the meta-aesthetic themes of The Sandman in which the nature and function of art is played out in relation to the machinery to which art is reduced in doll production (and is thence perceivable as a false art untrue to life) and one that speaks of fully embodied human performance (true art). At the centre of the ballet is the role of Dr. Coppélius, who through his signed communication (at least in the TV production I saw – and as explained for the BBC audience by Deborah Bull) makes it clear that he has made and fashioned the doll-daughter Coppélia. He shows by enacting it his intended delight in making other villagers (Franz and Swanilda particularly) feel themselves to be belittled by the cool disregard of the ‘real’ living people who observe his picture-perfect looking artwork, the said Coppélia. And since, as we have seen already, an on-stage audience gives credence to the excellence as human art of the virtuoso dancing of special individuals, throughout Coppélia the principals dancers give choreographically staged performances designed to engage an on-stage watcher as a recognition of their aesthetic value. The issue of staging dances for the principal ballerina is nuanced in the fine second Act, where Swanilda must perform as Coppélia would were she in fact really brought to life in order to convince the latter’s maker of her genuineness. The myth of Pygmalion is an underlying theme here obviously.

But Act 1 has already prepared us for this. For the theme of being persuaded to watch a performance appreciatively is how the characters relate to each other therein. It is emphasised in that my choice of preview preparation was on a BBC DVD version – the one by the BBC of the Royal Ballet performance of 2000. In this version, in two parts of Act 1, we watch the virtuoso dance pieces of the two main non-buffo characters from a vantage point behind the doll Coppélia’s head, as if from the imagined gaze of admiration at their dancing performance that both dancers wanted to excite in her. It is a hopeless hope, though they don’t know it, because Coppélia sees nothing though she may look at everything. It is, of course, an effect only a filmed version of a stage performance could achieve.

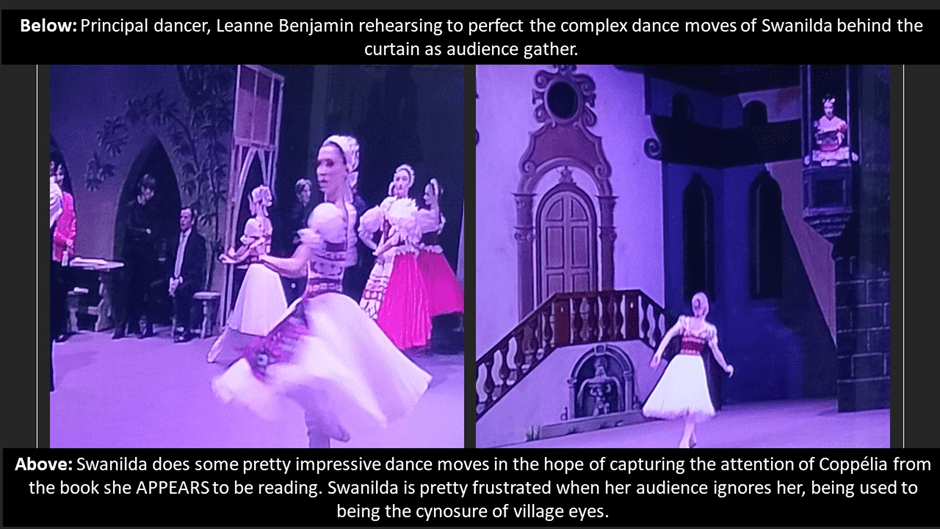

But even without this filmic perspective, the staging emphasises the self-conscious elicitation of someone to watching one’s virtuosity in performance and using it to evaluate oneself as the person watched, as both Franz and Swanilda do to the unliving doll in the window above them. Meanwhile, of the course, the doll’s eyes are angled at her book – one of the ways she is associated with a dry and lifeless (not obviously embodied) art. I try to show here how the watching of each other’s performance, where a sexualised- romantic outcome (or at least one involving scopophilia) is at stake. It is one of the queer beauties of this tale that Swanilda is as keen to attract Coppélia’s admiring valuation of her embodied motion as is Franz a little later. In the collage below (on the right) is part of the scene where she does it.

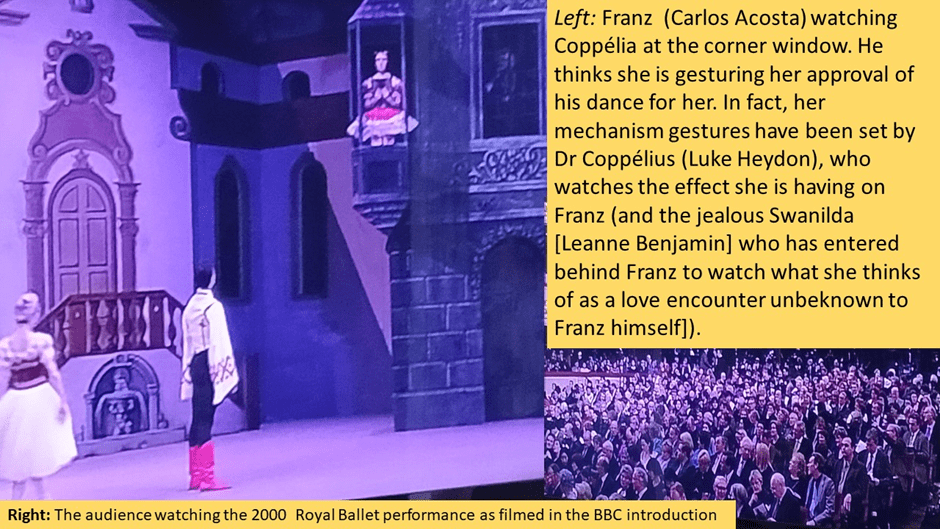

Now, although we need more than a still photograph to see it, Swanilda does some pretty impressive classic dance moves in the hope of capturing the attention of Coppélia from the book she APPEARS to be reading (for of course she can neither read nor see). Swanilda is pretty frustrated when her chosen audience ignores her, being used to being the cynosure of village eyes. And not only village eyes in the fiction of the ballet but also a real paying audience and even more the critical eyes of the rest of the company. This is a real consideration for a principal ballerina. We see this in the still I took of her (from the BBC introduction) that can be seen on the left of the above collage. We see Leanne Benjamin, whom in fact took the role of Swanilda at short notice due to illness of the intended star, engaged in preparations on stage behind the closed stage curtains as the audience assembled. She in this still invites without appearing or perhaps intending to, the eyes of the rest of the company to rest on her . This use throughout ballet stories of a kind of knowing pan-sexualised desire to have one’s body appreciated will be evident even more in Act 2. My next collage shows Franz at the same game minutes later. Franz (Carlos Acosta) is watching Coppélia at the corner window because he has boastfully told the audience (in sign language) that he has seen her watching him – and appreciatively. He thinks she is gesturing her approval of his dance for her in the still I show. In fact, her mechanism gestures have been set by Dr Coppélius (Luke Heydon), who also visibly watches the effect she is having on Franz (and the jealous Swanilda [Leanne Benjamin] who has entered behind Franz to watch what she thinks of as a love encounter with Coppélia unbeknown to Franz himself]).

My collage however is meant to show by using a still of the audience preparing to watch the production (from the BBC introduction again) that this request to be looked at and its interpretation of a kind of singling out (like that of artistic appreciation but in living analogy with sexual attraction) is important. It is important because this is something the doll herself can never do – not till she is impersonated by someone else, namely Swanilda. And this is, I would suggest, because (just as for Olympia in The Sandman) she is the product of an artist who does not know how to make his art live. The ballet however makes this point not by attempting to copy the various characters representing Sandman in the Hoffman story but by basing him on a cross between Pygmalion (who desired his own creations so much he wished them to be flesh) and Pantalone from the Italian Commedia dell’Arte tradition.

Of course Coppélius is an alchemist, as in Hoffman, but the metamorphosis of the unliving into the living is not the only focused issue for him in the ballet. It also utilises the supposed ability of alchemy to produce gold from common materials. Indeed the Doctor is pacified in Act 3 of the ballet by receiving gold directly from the Burgomaster as the price of his damaged stock of wooden dolls. This even turns him into a pleasant older gentleman who wishes well to the principals Franz and Swanilda, despite his attempt, some what unwittingly, to clone from them a bisexual being, a woman’s body with a man’s body energy and heartbeat, in Act 2. Here his stroking and clasping hands drag out this very man’s body energy and heartbeat by actions involving close contact with Franz’s drugged body. It is a beautiful scene of transcendent queerness.

Coppélius’ relationship to Franz is similar of Pantalone to Arlecchino : the old man, impotent but in imagined desire, yet with an ideal of female beauty as like youth itself and his to own and the young joker able to attract any woman. My next collage tries to help here, even evoking the many phallic symbols which connect the two men – the elder’s twisted stick and inhuman eyes and the younger’s thrusting body.

A collage relating to the relationship of the character of Dr. Coppélius with the Pantalone figure from the Italian Commedia dell’ Arte tradition.

Act 2 is as gorgeous as any ballet can be where bodies shape and re-shape physical space in time. Characters are kept in boxes or imprisoned by drugs but the body of Swanilda uses her enacted liminal state between death and life, false and true by drawing out of it a repertoire of very beautiful body movements. All involve the contradiction between the lifeless doll and the potential of desire and imagination to metamorphose into different shapes and identities – hence the ways in which Swanilda becomes many other of the doll stereotypes on stage with her whilst being able to also emerge from each shape. The idea is – how many bodies can I make live that once did not. As far as the Doctor is concerned, he has done this by consulting a huge alchemical book dumped on the central stage. It is only when he realises that he has been duped that we see Swanilda tear out the falsifying of this book, just as Goethe’s Faust too gives up books for life.

But between them both Swanilda and Coppélius also refashion Franz’s sex/gender, breaking down the dangers (to Swanilda) of his errant sexually multiple choice of love objects. In Act 1 he says he loves Swanilda but also falls, so easily for both Coppélia and another lady with whom he dances the Czardas. Life to Franz is clearly an opportunity to give short measures of commitment to any one women that is entirely justified by his skills in shaping his body with that of any lady whose gaze he can capture by his lithe virtuosity. Swanilda’s role in this Act is to be jealous, often to great comic effect.

But It is Swanilda who takes control of direction and performance of heterosexual interaction in Act 2, even accepting (imaginatively) into her body, though enacting the mechanical doll, the body energy and feelings of the man she loves and to which she is clearly bodily attracted. What is drawn out of Hoffman is that it is women who understand and are able to entrain men in perceiving the difference between an attraction to the mechanical in sexuality and what is more rounded and embodied imagination. This fires Swanilda’s ability to play both roles of the ‘living doll’ and the woman she would have that doll be – her best self. Again like awarding the dual role function of Odette/Odile to the principal ballerina in Swan Lake, what makes a ballerina a ‘Principal’ is foregrounded. The point is to break the doll from the frame working of the box her father creates around – and boxes and window frames are legion. Her father gives her the name she bears but also makes her literally out of wood that can not be touched. Only when a man shows enough sexual interest to shimmy up a ladder does the father release the violence against him which also births his reflected desire to make his daughter live and dance. He does this by drawing out the male spirit (the masculine form) of Franz whose body he strokes. Wanting better results he mimes wrenching the heart out of the man, allowing Swanilda to introject a male spirit and feelings as an androgyne.

In this imagined role she liberates both Franz, and herself, from the old man’s spell, liberating the doll at the same time from her ‘father’s house and enabled the recognition that she is a lifeless automaton. In my collage I show Swanilda and her corps troupe confront the doll in her box where she still appears to bear the power of a beautiful woman of higher class than themselves (they are tradesmen’s daughters) and where she lies obviously lifeless – perhaps even dead because what she is now introjected by Swanilda and patriarchy (father with his stick and the once non-monogamous youth sowing wild oats) is forced to realise the real power of real women rather than ideal external stereotypes of women (dolls).

When the old man blesses the marriage of Franz and Swanilda he reverses both the deceit with which he tempted couples to suffer the temptation of another more beautiful looking woman and his own rather crabbed desire for a girl of his own making, we see him pay homage to in Act 1. As I say in the collage below there is a deep meaning here for in patriarchy, a doll is a Man-made Woman ‘boxed in’ and framed by the Name of her Father. She is a kept woman in every sense of the word: fathers distrust the desire of men, because they know & fear themselves and punish their girls for the fear they blame the girls for, which is in fact the reflex of their repressed incestuous desire.

Now, it is has taken me a long time to get round to the production we will see In September, which is that of English Youth Ballet. It is my hope that this company will not merely ape the practice of older companies but play for what it is worth the nuances in the ballet between older age and youth; the desires of a community to reproduce itself exactly as a tradition and the duty of youth to make it new and innovative. Let’s see. I am looking forward to the production. I hope you are too Rob, Linda and Justin, though I sense only Linda is likely to read one of my boring blogs in the first place.

All the best

Love

Steve

[1] E.T.A. Hoffman (trans. Peter Wortsman) [2016:20] The Sandman Penguin Classic (Kindle ed.)

[2] Ibid: 17

[3] Ibid: 37

[4] Ibid: 38

[5] Ibid: 22

[6] Ibid: 26

[7] Ibid: 40f.

[8] Ibid: 46f.

[9] ibid: 54

[10] Sarah Crompton (2019) ‘Coppélia review – Francesca Hayward captivates’ in The Observer (Sun 8 Dec 2019 05.30 GMT) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/stage/2019/dec/08/coppelia-royal-ballet-review-francesca-hayward-ninette-de-valois-delibes

One thought on “Art about itself: artistic making in Hoffman’s ‘The Sandman’ and sculpted scopophilia in Léo Delibes ‘Coppélia’. A review of the BBC production (on DVD) of the ballet restaged from an earlier production by Anthony Dowell. This blog acts as my preview of seeing a live performance by the English Youth Ballet in Sunderland in September.”