‘A girl is a pit oss, a thrush, a white ferret, a lark. / A girl is cream rising thick as desire in the dark’.[1] The edginess involved in an attempt to truly represent girl children in narrative formed from lyric verse. I am not fit to judge this but stand back amazed in my blog on Liz Berry (2023) The Home Child London, Chatto & Windus.

The author and the book

The Home Child tells the story of some of many, focusing on her own great-aunt Eliza Showell, migrant children, shipped from the Black Country with dialect intact to Canada to work as unpaid (and most often unloved if not grossly abused and many were) servants to farmers families. In describing the research with older people who were once these children to Jen Campbell, the disability rights campaigner, Liz Berry says this of them:

Something that touched me very deeply in my research was the way the children spoke, time and time again in their interviews and letters, of being made to feel like animals in their lives as young migrants. That idea of creatureliness, of becoming part of the beyond-human world, is woven throughout The Home Child: the children are sparrows, wildflowers, seeds, cattle, foals, dogs, piglets, trembling aspens… Yet, also held within that motif is the redemptive idea that animals might be the gentlest and noblest of us, that it’s an honour and a blessing to be among their kind.[2]

I have difficulties with some of this as a reader of poetry for it tends to sentimentalise, even in the evocation of redemption, or ‘blessing’, as a quasi-post-religious idea, as what both poetry and the love of non-human natural life might be. They are described in terms like ‘the gentlest and noblest’. However, the latter are highly constructed human values, marred with the history of class as well as the traditions of sympathetic identification with what is supposedly of value. This is so much the case that Dickens took two great novels – David Copperfield and Great Expectations – to work out the idea of what might be meant by the idea of a ‘gentle – man’ in a society wherein values where challenged by both changes in the nature of social authority, hierarchy and the contamination within it of what Thomas Carlyle called the ‘cash-nexus’, the transformation of human relations into underlying hidden monetary transactions. The list of little and vulnerable (‘aspens’ after all don’t ‘tremble’ in the way we are invited to see them doing) thinks includes nature in its supposedly regenerative youth, still little and vulnerable to human or other exploitation – ‘seeds; for instance and ‘foals’ and ‘piglets’ rather the adult versions, even when balanced by a less focused category, in age terms, like ‘cattle’. Is this what happens in the dramatic lyrical narrative poem though. For instance in reading the lyric ‘A Girl’ the animal metaphors feel more mixed in the lines I cite in my title:

‘A girl is a pit oss, a thrush, a white ferret, a lark.

A girl is cream rising thick as desire in the dark’.[3]

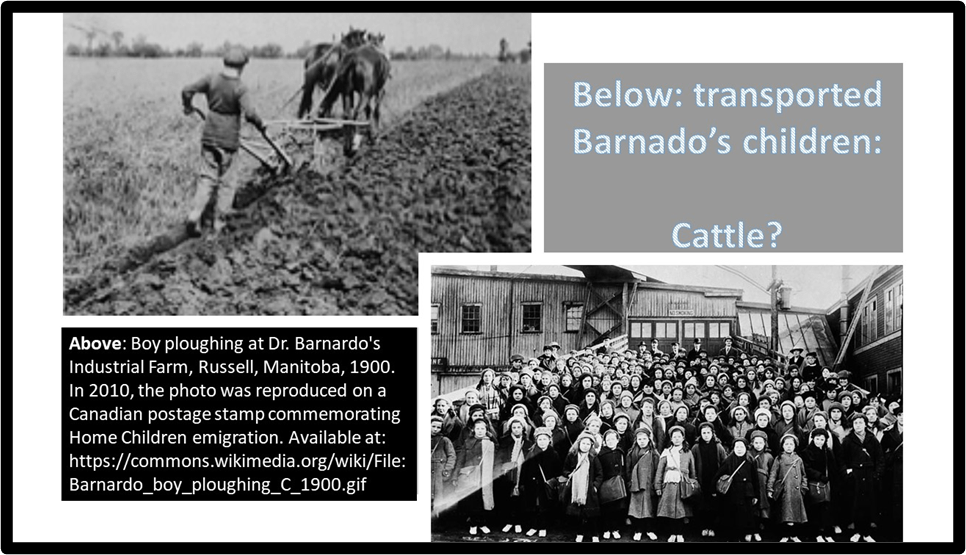

Here is no sparrow but more dynamically, and song-associated, birds: ‘thrush’ and ‘lark’. A ‘white ferret’ may associate with the petted variety of the kept animal but ferrets are dangerous and nuanced. And although a ‘pit oss is there to show the Black Country credentials, in dialect and chosen kind of animal, the sentimentality around pit ponies is marred with the knowledge that here animals are at their most vulnerable to human uses and misuses of them: the degradation of life working underground for animals who feel the deprivation of a truly ‘natural’ environment. The history of home children has a similar ambivalence over history. So sure were early pioneers that children-in-care from backgrounds considered deprived or unethical were being freed from an unnatural life that the picture below of a lad managing a fearsome team of farm ‘plough-ossess’ shown below was seen as a boast for the scheme worthy for postage-stamp reproduction and distribution.

It is difficult now for us to see such pictures, intended as memorials of grateful children redirected to a new life in the colonies, as pictures in line with the massing of the vulnerable like the cattle they were expected to work by a haplessly unempathetic bourgeois social work profession of the time.

So what does Berry intend? A list of examples of a redemptive nature to describe Eliza Showell. Certainly Eliza is not immune from such dreams. In the deprived urban squalor of Silver street, Bilston, the working, and home, environments are as hellish as social worker of the time saw them, if the earth of the foundries ‘spews sulphur’, even the air is ‘drunken’. The area is characterised by the ‘mishkin’ : which a useful glossary of Black Country word translates as a ‘communal rubbish heap or dustbin’.[4] Eliza’s dream is of a working animal in the Bilston street freed to become the shire horse worked: ‘She dreams of horses: // The mare that draws the soil-cart through the reisty dark,/ Its silvery shoes agleam in the muck, …//… she is riding / Bareback across the leasowe, beyond the town’s rough hems, … that terrible hovering rook of the workhouse’.[5]

And this is what the social workers did not see – that England had the space for freedom outside the ‘hem’ of its urban spaces (dressmaking metaphors are common for that too characterised labour – low paid female labour) and yet was married still to the solution provided by the ‘workhouse’ of the 1833 Poor Law Reform Act. And nature is thus mixed – the foreboding destiny of workhouse’s is like a dark rook. Hence, I cannot see animals merely playing a redemptive role in the poem as Berry suggested to Jen Campbell – they too partake of the hell made for them by human distributions of fortune, by mass capitalism. And Eliza is not a simple ‘girl’ yearning for innocent freedom. Her being is attuned to the sexual associations in English lyric of the ‘thrush and the ‘lark’. And how are we to read that tense line: ‘A girl is cream rising thick as desire in the dark’, for it is as lurid and dark (in the sense of having deep as well as potentially negative meaning) as it is a picture of supposed liberation. Whose ‘desire’, after all, is ‘rising’ here. In a sense, we shall see it will be Eliza’s who finds redemptive liberatory sexual love with the male home-child, Daniel: a ‘heaven’ that is ‘… A nest of warm grass, / the stream’s long drink / and blueberries, sharp and guttly, giddying our lips / like we’m canting of love’.[6] ’ But it is also the ‘desire’ of the rich male – the only one after all able to afford the richly made coffee with cream in this metaphor and another dark potential in the history of girl home children – to fall through the net of supposed protection in form of work often beyond their capabilities and of certain soul-destroying repetitiveness into street prostitution.

I may be wrong to see those echoes and hints and the rather sugary interview with Jen Campbell (not known for her sugariness when it comes to standing up for those at risk of exploitation in society) would suggest I am. Hence I leave that for any reader here to find themselves at the link I have already given in a footnote above. Ruth Padel, herself an amazing poet, reviews it more as a continuation of Berry’s project from her first volume of poems onwards, which: ‘fused the personal and political with disarming tenderness, its soaring imagery and soft dialect words from the West Midlands making beautiful whorls in the grain and flow of its music’.[7] But, despite this reference to the ‘political’ fire in the discussion of the ‘personal’, I miss in Padel’s brief account some of the grit I find in Berry’s exquisite use of language to suggest the darkness, as well as the sugar, implied in her characterisation of young female lives. Of the ‘aborted love story’ (her words) with Daniel she says that it achieves the following: ‘The cruelty is intensified, but also redeemed’ but here again redemption is proven by an image from the life of overworked farm horses: ‘… and both of us so frightened, / blind as moles. But wanting / something. Wanting. / We’m side-by-side on the grass, / my barefeet in the water / bowing our heads, gentle / as osses at the water-trough.”

Why, oh why, I ask myself do critics (especially poets) see images of abject subjugation (‘bowing our heads’ even if at moments of meeting needs) as redemptive. Maybe they should try a working horse’s life sometimes. Here nature is blinded and bowed because it either does not understand or is not able to articulate its ‘desires’ for freedom to name one’s own goal: ‘But wanting / something. Wanting’. I feel that wanting as ‘longing that the sexual charge of the poem alone does not satisfy. Padel is still correct to say that what is longed for is something to call ‘home’ ( a theme too in Caleb Azumah Nelson’s Small Worlds which I will blog on next). Padel says beautifully, almost at her review’s end:

“Home” proves to be other people, the feelings you have for them, and when you lose them, the memory of those feelings. The Black Country word for “home” is wum. When Eliza thinks that she has lived her whole life without a home, “I send myself back to that hour in the woods / when he first took my fingers / and touched them to a leaf. / Feel it, he said, They call it a lamb’s ear. / He was my wum then”.[8]

I agree of course in terms of the poem’s deeper structural move towards the theme of ‘wum’. But the ‘home’ achieved in the poem itself is not a redemption, except in memory. Daniel, whose night with Eliza is discovered, is after all sent to a farm in aptly named ‘Wolfville’ and for him and for Eliza, ‘no wind can ever blow here but ill’.[9] I don’t see redemption here but in continued longing for what is lost. The real Eliza ‘died in a senior home in Inverness, Novia Scotia, in 1978’, her small headstone purchased by former employers. Bowed down in the trough indeed: noble yes and worthy of commemoration but not ever the stuff of quasi-religious redemption, and her real life, still effectively censored from history, like her redacted letter-poem to her brother Jim, censored by ‘caring’ authorities in an attempt to eradicate family ties.

Liz Berry’s discovered photograph of Eliza, Eliza’s gravestone at Malagawatch Cemetery and the poem-letter to Jim (repeated). Respectively my photographs from Berry (2023), pages 109, 110 & 27.

But if we return to the poem entitled A Girl and to the companion to it (but not titled though bearing the same repeated phrase ‘a girl is …’ at each of its lines, it feels to me at least that Berry is examining physical femininity, and the nature of female ‘wanting’, including the inevitable associations in our culture to a cut, a hole, and an absence (a ‘0’) , all the more to emphasise a female presence that, if free would be a positive power rather than a negative deficit of such. Look at the way the images make her a positive in an absence or vacuum imagined by others, with the associations of the empty and hollowed object : a ‘slit, an ‘O’ or ‘clem-gutted’ hole, and a ‘shaft’ yield ‘a new penny’, ‘a bulb, greedy for light’, ‘a crowning-in’ and a ‘glede’ in The titled version.[10] In the untitled version of these lines, the final assertion is: ‘A girl is a tinder box to light all the world’s wanting’. This ‘tinder-box is an explosive, almost revolutionary presence, politically lighting up the issue of WANT, with which Eliza has been associated. In this list we start with the girl as vulnerable, as a raindrop is in being absorbed by a lake , or ‘ivy’ in the ‘arms of an indifferent tree’. But thereafter she becomes a sign of sleeping hope like a swift asleep but still aimed at its goal ( ‘a horseshoe’, a ‘freckled egg’, a ‘swift’) over a landscape marked by the devastation of want (‘ruin’s blown door’, ‘shit-crusted straw’).[11]

Even those home-girls who ‘broomed our floors, raised our children’ as Canadian colonists may sing since these grown girls are like the beeches in the cemetery of Malagawatch had ‘no roots deeper / than driftwood borne by the ocean’.[12] How are we to take this? Not, I think by sentimentalising stories of the lost girls of colonial history as somehow nobler and gentler than they could have conceived themselves but as a piece of grit that warns bourgeois history that it feels it rids itself of working class or poverty-born peoples by expulsion or marginalisation, for their return will be the fire of revolution. We need to remember that Eliza may have dreamed of the rural but that her origin was another absence, a hole, but actually filled with fire – Fiery Holes in Bilston. For in this poem is the theme of Eliza as the spirit of fire that does not, but might eventually be the ‘tinder-box’ to set alight the bourgeois world and clean it of its dirtying complacency where it used even the children of the working-class, and in my view, still does:

Her brothers, the steelworks, the sweltering chapel.

That terrible hovering rook of the workhouse.

Dreaming. Dreaming. The air blown spotless.

All the blackened sparrows lift their voices – [13]

This is not the charming redemptive innocent in the interview with Campbell or even Padel’s review, with its ‘warm’ dialect word-praise. It’s this girl who on admission is not seen, not yet, bowing her head in submission but spits, as she says herself: ‘Piss off, I spits, my donny clamped to my lips, …’.[14] She is the one in whom: ‘everything in me squeals / to be bad’, even in a poem with a name like a standard phrase from a patient and conventional girl’s sampler:Tis So Sweet to Trust.[15] She may be a redemptive animal image, but isn’t the redemption, Blakean infernal and ‘dark’:… she held / her foal heart, its dark blessing / a-burn inspite the blizzard’.[16] Though the owners of her life may censor the fact of her labour, this woman is the soul of a burning lost socialism, her voice, as her teachers say, ‘quite the sound of a navvy grinding lime in the quarry’.[17] And her link to Daniel is masculine – her deep soul outside gender. They talk : About my brothers. Wum. Fiery Holes’.[18] His gift to her may be a girlish ribbon but ‘it glows all night. / Little fire’.[19] It is another memory of Fiery Holes.

I am aware I stand alone against much feminine and even authorial voice but poetry breaks boundaries and for me this poem does in ways the descriptions I’ve cited of it don’t. in a sense, I think this is because this is a very good dramatic lyric narrative, the voice as Browning said of his own Dramatic Lyrics and cited in this webpage:

Browning himself summed up Dramatic Lyrics as a gathering of “so many utterances of so many imaginary persons, not mine,” and the sense of an authorial presence … is indeed diminished in the wake of the control the [speakers of the poems] (seem) to wield over the poem.[20]

Do read this wonderful poem.

Love

Steve

[1] Liz Berry ‘The Girl’ (2023: 38) in The Home Child London, Chatto & Windus, p. 38

[2] Jen Campbell (2023)’ Interview blog on The Home Child by Liz Berry’ with the author for Book Club, TOAST Magazine (online) [22 March 2023] Available at: https://www.toa.st/blogs/magazine/the-home-child-by-liz-berry-book-club

[3] The Girl in Berry op.cit: 38

[4] Ibid: 113 for Glossary

[5] Fiery Holes: Bilston, June 1907 in Berry op.cit: 7f. (reisty = dirty or smelly; leasowe = meadow ibid: 112f.)

[6] There is a Land of Pure Delight in Berry op.cit: 86. (guttle = chew or gobble, canting = talking ibid: 112f.)

[7] Ruth Padel (2023) ‘The Home Child by Liz Berry review – a long injustice’ in The Guardian (online) [Wed 5 Apr 2023 07.30 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/05/the-home-child-by-liz-berry-review-a-long-injustice

[8] Ibid.

[9] Wolfville in Berry op.cit: 96

[10] The Girl in ibid: 38 (clem-gutted = starving, glede = cinder ibid: 112f.). I cannot find the meaning of a ‘crowning-in’, although in modern urban dialect it indicates a presence making itself felt in the anal shaft.

[11] ibid: 100

[12] Malagawatch in ibid: 101

[13] Fiery Holes: Bilston, June 1907 in ibid: 8.

[14] Admission in ibid: 16. (donny = hand ibid: 112f.)

[15] Tis So Sweet to Trust in ibid: 54f.

[16] Darling Foal in ibid: 57.

[17] In the Schoolroom in ibid: 67.

[18] Canting in ibid: 80.

[19] The Gift in ibid: 83.

[20] Adapted from NASRULLAH MAMBROL (2021) ‘Analysis of Robert Browning’s My Last Duchess’ In Literary Theory and Criticism [MARCH 30, 2021] Available at: https://literariness.org/2021/03/30/analysis-of-robert-brownings-my-last-duchess/