‘But they seem to work, accompanied by an ensemble of silence’, says Simon Armitage in the ‘INTRO’ to his new collected versions of the song lyric.[1] This blog reflects on the published song lyric as part of the ‘repertoire’ of an oral poet. It focuses on Simon Armitage (2023) ‘Never Good with Horses: Assembled Lyrics’ London, Faber & Faber and on seeing him read, with @JustinCurley4 at The Queens Hall, performing for Hexham Literature Festival on Friday 29 April 2023.

Book cover and my photographs (details) of Armitage playing with his band LYR in Durham Cathedral. See latter At: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/07/16/firm-as-a-rock-we-stand-the-banner-sings-but-a-limestone-arch-thrown-up-in-the-year-dot-collapsed-in-pity-after-the-last-door-was-slammed-shut-a-marooned-stack-now-sulks/

I have for some time believed that Simon Armitage had an issue with how poetry is misrepresented by people unwilling and unable to learn that it involves capacity for the work of learning and skilled crafting that marks the ‘finely honed poetic sensibilities and control of language’ that alone defines it rather than any specialism of form or content. In my understanding of his thinking, here is no reason a song lyric cannot also be poetry, though it remains the former thing too but it cannot claim to be poetry without also having those qualities marked in the definition above. These terms indeed come from his discussion, using Christopher Ricks as the straw man representing all those persons in universities whose knowledge of poetry is entirely confined to academic commentary in order to query their authority to make claims about what poetry is or and what it is not. In this discussion, cited already by me in a blog available at this link, in A Vertical Art: Oxford Lectures in 2021, in order to justify his view that Ricks is entirely wrong to ‘credit’ Dylan’s song lyrics with the attribute of poetry he says that lyrics cited by Ricks are:

littered with errors – or at least strewn with chances for improvement – and I deem it a mistake to credit Dylan with the kind of finely honed poetic sensibilities and control of language that literature would normally expect of its decorated practitioners.[2]

We should not make the other mistake however possible here, which is to believe that, since Dylan’s lyrics are not always admissible as poems, they are not great song lyrics. When I cited this in an earlier blog I did not know that Armitage was and remains a fan of Bob Dylan. Simon Hattenstone in a Guardian interview with Armitage makes the same point.[3] , he also provides a link to an incredibly positive evaluation of Dylan written by Armitage in a piece published in The Guardian in 2016.

Finally, a friend had to intervene. A Dylan anorak of the first order, I don’t think he could stand it any longer. Like there was something very obvious I needed to know, a sort of Bob Dylan birds-and-the-bees conversation that needed to be had. He taped me Blood On The Tracks and Blonde On Blonde, and handed them over in a plain brown envelope. I played one in the car on the way to work, then knocked off early to listen to the other on the way home. And suddenly it all made sense.

A few years later he taped me the Bootleg Series, I-III, on three cassettes. I was, by this time, something of a fan, ranging forward and back through Dylan’s output, having bought periodicals and biographies to map out the route.[4]

This is more than enough background to seeing the importance in Armitage’s INTRO (named to match the fact that the book also has an OUTRO rather than an appendix) of his praise of the independent power of music that is quite independent of what we sometimes call the ‘music’ of verse – effects of assonance, rhyme, metre, rhythm, and repetition. Song lyrics have these elements too, as Armitage said in his INTRO too, but they do not need to be poetry though they may be. Even when composed by Armitage, in a manner he somehow sees but cannot define other than it being different and requiring ‘self-inflicted intensities’ from its practitioner. Yet he makes it clear in the light sentence I use in my title that though all the lyrics ‘assembled’ together in this new volume may evoke music so much that when he reads them to himself ‘sans music’ (at least externally), he still cannot be ‘sure how they sound, out loud’ and that is because ‘at the back of my mind I’m hearing melodies and time signatures and chord structures that aren’t apparent to anyone else within earshot’.[5] The only conclusion I can draw from this is that Armitage does not feel comfortable with assimilating those sound effects in poetry and lyric into non-vocal music (whether that of birdsong or instrumental solo or ensemble pieces) per se – printed words alone do not have ‘melodies and time signatures and chord structures’, which can only be analogies for the sound effects in oral poetry or poetry silently read as sound within a reader’s head. The INTRO makes no absolute judgement here as its final two sentences show. These sentences evoke the relative presence and absence of ‘something’ or other in each that distinguishes them but collapse in on themselves as attempts to state a final distinction by confessing that the stuff of song lyrics is a ‘a notion I’m still processing’.

Personally, I am happy to embrace Armitage’s sense of a meaning not quite yet emergent when speaking of the distinction between the music necessary to but absent from the song lyric and the rather different tonal and sound variation of poetry when heard aloud. Further we need to ask what the ‘ensemble of silence’ in which a verbal lyric without musical accompaniment is instead ‘accompanied’ in the Armitage quotation in my title. In my view we cannot read this without reference to the importance Armitage has, as a poet – especially lately, given to themes of accompaniment – a word signifying a meeting and travelling together in a ‘company’, a companionate group or ‘ensemble’ of people, in some poems and statements a ‘congregation’.

Take a look at how I have looked at this for instance on a past blog on a performance of one of te lyrics first published for a reading audience alone in the current volume, Alchemy. Here is part of my reading of this when I saw it performed in Durham Cathedral:#

… songs in this collection imagine the complexities of mining communities and their expression in brass bands, as in the wonderful song Alchemy, wherein only performance can show how revival is intended. The first use of the word ‘brass’ in its lyrics connotes the Yorkshire idiom for wealth (‘And out of the fire came brass’). The constant repetitive play in the second stanza of the ‘out of the brass’ phrase refers to the heard revival, by a live audience, that bursts into the performed song by the swell of its working class community brass band backing – on this evening provided by Easington Colliery Band. This ‘accompaniment’ and deepening of the word ‘brass’ seems to breed symbols of power within the poem; a power won by a class of workers instinct with vision and dreams as well as a new revolution of cleansing fire that had first created it. The song becomes a version of the Creation or Re-Creation myth but not one performed top-down by a God but bottom up from the Earth:

Out of the earth came light.

Out of the earth came breath.[6]

I clearly see the theme of longed-for accompaniment too in seeing Armitage’s wonderful collection The Unaccompanied as bearing its ghost – a reflection on why poetry became, with Wordsworth perhaps more than any other a matter of an ‘ensemble of silence’, a hymn to solitude in which companionship may only be imagined or ‘recollected in tranquility’:

Hence, a poem that starts with a sorry ghost of Wordsworth in the ‘corpse road’ from Dove Cottage, ends with a kind of secular communion of company that is both also a sorry ghost of community but an admission of its underlying potential. It is as potent as the ambiguities in its half-rhyme (tarn / cairn):

Then I hacked up the ghyll to higher ground

Counting the hikers striding along the ridge,

Thinking of taking a drink from the tarn,

Thinking of adding a new stone to the cairn.[7]

Song Lyrics then are always accompanied. They rejoice in congregational reality – the necessity of more than one person and one source of sound. Is this how we should approach then the lyrics, collected in an ensemble to accompany each other into the canon of this poet’s work from across his career in Never Good with Horses: Assembled Lyrics. There are clues that this might be a strongly intended reading in Simon Hattenstone’s interview with the poet. Not this for instance when Hattenstone suggests that one criticism of his lyrics might be that ‘they read, and sound, like poems’:

He nods. “Lots were written as poems or with my poetry head on, with the idea that they’d be accompanied by music. There’d be some emotional engine attached to them.” When he performs them with LYR, he speaks them to ambient music rather than sings them.[8]

Voiced poetry becomes the lone non-instrumentalised thing in these concerts – as Geoff and I witnessed at the Durham Brass Festival event in Durham Cathedral. It speaks alone against an ‘emotional engine’ (instruments that carry emotion through the pure non-verbal communication through sound they emit. Though Hattenstone possibly does not intend this, he certainly makes both meanings of what it means to be ‘accompanied’ here available to us in his gloss on Armitage’s method: being the sole lonely speaker in a mass of ‘ambient music’, a music only ambient because performed by other artists.

Music carries unvoiced (unspoken) emotion in the content of some of Armitage’s lyrics, as in the beautiful and wondrously emotional plea (written during lockdown) of an elder lady attempting to voice her incomprehension through the fog of dementia as well through a window which both silence her speaking voice. Her ‘special tree’ and ‘favourite bird’ do have names but they can only be ‘mouthed’ back to her through the window which bars their hearing, for she ‘asked again’ what they may be: ‘the song thrush and the mountain ash’. These elements of a living world are cut off from the woman on the other side of the window and who, in the final stanza must have died. The unspeakable emotion of this poem is occluded in the musical accompaniment this lyric lacks, like the lost scent of flowers, the COVID acquired loss of taste in food, the unseen faces of nurses and the ‘shut’ park gates, ‘boarded up’ shops, swings on which to play in ‘knots’: ‘And the music … why had the music stopped’.[9] This lyric’s stanzaic form, rhythm, rhyme, and repetitions of course have their music but they do not carry to their listener who has lost the capacity for music, the loving feeling of being accompanied without barrier. Likewise an earlier lyric, since it mentions as a contemporary the pipe-smoking Labour Prime Minister, Harold Wilson sets political voice against the music in ‘song’:

Till the world discovers its voice again

We’ll sing, we’ll sing.[10]

In another lyric, produced for a Channel 4 art-documentary in 2002, Feltham Sings, Armitage has written lyrics for young men and boys in Feltham Young Offenders Institution (YOI), which they sing, rap or voice (the second link may lead you to the recording on You-Tube). One, is a list poem whose subject is by violent suicide by overdose (where possible), cutting, or hanging – a fate too often of marginalised young men in such YOIs. It’s a lyric that defies the music it invites in the over-repetitive rhythm of pursuits in prison (‘the drip, drip, drip of a ping-pong ball’). These young men’s lives were subject to ‘prison’ which is ‘a disease called boredom’ before prison for their lives were lived without safety and security from the others who were their only company and the singer says ‘I was once manhandled by babysitters’.[11] This knowledge from the marginalised and unaccompanied by music or persons ready to act in concordance with each other’s interests was one Armitage inherited from his life as a probation officer. Hattenstone asked the poet about this past career in fact, exploring the genesis of some of his early poetry’s content.

… He then followed his father into the probation service. He did his social work and probation training in Manchester, and went on to do a master’s at the University of Manchester. … For the next eight years he was a probation officer by day, a poet by night. The job provided source material for his poetry. / … Did the work have an impact on him? “I ended up with a very bleak view of the world. Every day you were encountering very upsetting or grim situations. …”. / … “I went in because I wanted to help people. I was a do-gooder, I wanted to do my bit.” He bites hard on the last word. “And I lost faith in the idea that I could make any difference. I’m quite a sensitive person and I don’t think that’s an ideal personality type for that kind of work. I took it all very personally.”

Does he still carry that heaviness from the probation years? “Yes. There’s a quite a lot of violence in my poems. They tend to be on the cynical and gloomy side. I don’t know whether I can blame it all on probation. Maybe there’s something pessimistic in me.” I remind him of the bands he’s adored since his teens – the Fall, Joy Division, the Smiths. Not light there much. He smiles.[12]

Photograph available from its maker: Heather-Louise Devey on Twitter: “Magic to hear Poet Laureate, and wordsmith for @LYRband, Simon Armitage in Hexham tonight. I love how he brings light to small, overlooked details in nature that become a backdrop to everyday life. There’s beauty in the detail 🌾 https://t.co/SGB77xu1h4” / Twitter

There is so much in these passages from the interview that was important to me and it is information that Armitage repeated very movingly in answer to my question from the floor at the Hexham reading (see photograph above), about how some of the lyrics – I instanced the lyrics 33 1/3 and Greatcoat – absorbed both his characteristic humour (‘wit’ perhaps in the seventeenth century sense) into meanings, sometimes meaning in the form of mere metaphoric conceits, that included reference to violent death by suicide. He traced this to deeply stored memories of probation – in those years, as I knew for I was trained in the final years in which probation was the responsibility of social work departments in universities, more like social work than is the case now. Armitage’s ‘sensitivity’ is rarely discussed but it is of the kind that responds to the tragedy of exclusion from communities of love and support that is too often the experience seen in their ‘clients’ by both social workers and probation officers then. What also speaks out is Hattenstone’s suggestion that some of this bleakness was a possible result of some of the music he favoured. I have learned since, from Justin who was with me at this event, that both his favoured music and probation may have had commonalities for some poems and we have, since he returned to Manchester, spoken a lot about one of the early lyrics in this volume, which refers directly Manchester experience, Down on Mary Street.[13]

Justin said that though this is now a somewhat ‘gentrified’ area, almost in Salford near the River Irwell, it was easy to characterise as a ‘poverty-characterised life of people often thought of as an ‘underclass’, where a ‘life is over before its begun’ mood in it. He felt this captured in the ‘bleak but beautiful’ lyric: in a ‘no hope environment’ such as that spoken about by the poet being ‘inside or outside prison makes little difference’ to people in it since their ‘” free” lives are almost “institutionalised”. He went on to say (and I can only agree for this says it all better than I could) that the ‘narrator of that poem knows that the people represented in it will always be ‘institutionalised – they will always be on ” Mary Street”’, wherever else they are. ‘Wherever they turn they will never be “free”’: their environment conditioned by early ‘poverty, lack of education…will always be a prison of kinds’. He added that the area is ‘not far from Strangeways prison. It looms large in local culture- and he told me (for it is not in my culture, as he knew, that the Smiths (that group loved by Armitage and whose singer, Morrisey he had uncomfortably interviewed – as Hattenstone tells us) wrote Strangeways Here We Come and the film of the same name made to reflect the Smiths’ album, about the prison and about local male group expectation of this prison as an expected life outcome for them. He added further that Armitage would have been very conscious of The Smiths take in the 1980s on Thatcher’s Britain’.

I couldn’t after that say much that wasn’t said here already – the strong political force of the poem is clear to see, but its quiescent despair had not properly struck me, though it ought to have done. There is a lot conveyed here simply in the lyric’s recurrent use of ‘down’ as an emotional as well as a directional marker in local dialect and in characterising the hierarchy’s effect on the people of the then Mary Street. It is no doubt the view of the disillusioned probation officer rather than of the people themselves and may lack nuance around how they themselves see their communities, but without doubt this is a lyric about the absence of social music and the alienation of a girl ‘scary Mary’ by mental illness caused and exacerbated by social trauma, by the lack of protective supportive community, accompaniment in raising her voice.

This is a tremendous book, which needs to be read right through before you pick out single poems. I have, as a result not picked my favourites though The Songthrush and the Mountain Ash is one but leave that to each reader. But I would claim that there are exemplary poems of summary of the whole – notably Paradise Lost. Whilst this lyric inevitably recalls the Fall motif of Milton, its real fall is of the ambition to build even a sense of home community that offers security, let alone happiness and pleasure. So much and so many events from popular culture’s degradation by capitalism lies in the warehouse section whether we see it as hapless criminals on a robbery, entering Amazon fulfilment centres for work, or the shape of modern retail. These lines are central:

Get engaged then hitched

in an Easter Egg church –

raise a family there –

build a decent home

in the soap box suburbs –

in the neighbourhoods

of pallets and crates –

in the tea chest estates.[14]

And there s much fun here. Guernica Jigsaw is surely a more modern satire on the collusions which end community, such as the elitism of private art, even when supposedly publicly owned and the nonsense of City of Culture bravado[15]. I think Presidentially Yours (and its illustration, must be about Trump (‘Kill the booing and roll the applause’) in whose place community has given way to lies to support the ultra-rich.

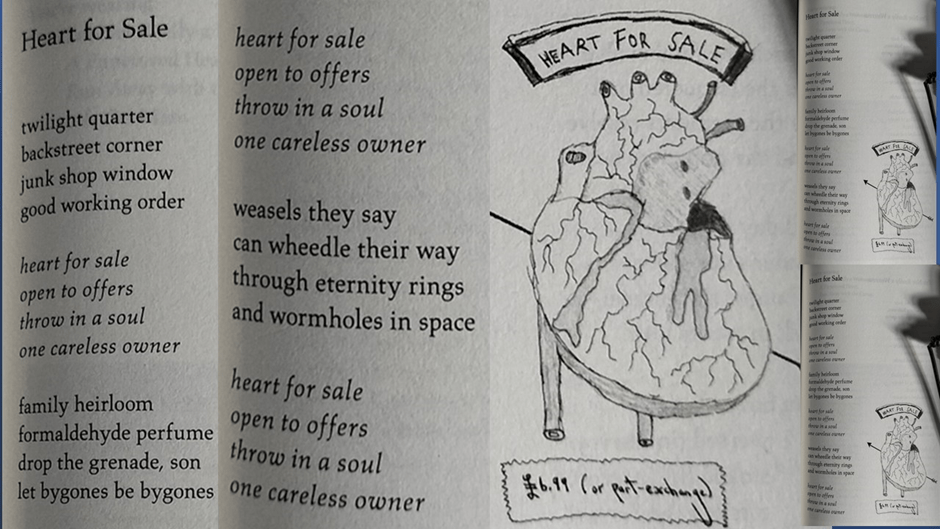

And let’s give a heads-up to the wonderful illustrations here, surely by him – frank, funny and fabulously ‘unprofessional’. I loved the octopus with only seven boots but the one accompanying Heart for Sale is the best advert for Blatcherist individualism and the commodification that went with that ideology of market values.

Read these lyrics. It’s a fabulous book to own.

All love

Steve

[1] Simon Armitage (2023: xiii) ‘INTRO’ in Never Good with Horses: Assembled Lyrics London, Faber & Faber, ix – xiv.

[2] Simon Armitage (2021: 127) A Vertical Art: Oxford Lectures London, Faber & Faber Ltd. My italics/

[3] “Armitage draws a clear distinction between lyrics and poetry. “My complaint is when song lyrics are taken out of their context and presented as poems.” Can he provide an example? “Yes. Sometimes with my students, I take in Bob Dylan lyrics. Dylan is often talked of as a poet. I give them the lyric and usually they don’t know the tune and they say, ‘Well, if this is a poem it’s a really bad one because it does all the things you’re not supposed to do in a poem – cheesy rhymes, mixed metaphors, tautology, oxymoron, everything.’” From: Simon Hattenstone (2023) ‘Interview: ‘I’m a CBE, I’m poet laureate so I’m clearly not a republican am I?’: Simon Armitage on his radical roots and rock star dreams’ in The Guardian online (Sat 8 Apr 2023 11.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/08/simon-armitage-poet-laureate-radical-roots-rock-star-dreams

[4] Simon Armitage (2016) ‘Why I took the slow train to become a fan of Bob Dylan’ in The Guardian online (Fri 14 Oct 2016 19.04 BST). Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/oct/14/why-i-took-slow-train-to-become-fan-of-bob-dylan-simon-armitage

[5] Armitage (2023) op.cit: xiii.

[6] From my blog at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2022/07/16/firm-as-a-rock-we-stand-the-banner-sings-but-a-limestone-arch-thrown-up-in-the-year-dot-collapsed-in-pity-after-the-last-door-was-slammed-shut-a-marooned-stack-now-sulks/ Alchemy cited here from the performance programme but also in Armitage (2023: 88f.) op.cit

[7] From Reblogged: Simon Armitage (2017) ‘The Unaccompanied’ VERY PERSONAL REVIEW – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog) Available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2019/12/07/594/

[8] Simon Hattenstone (2023) ‘Interview’ in The Guardian online (Sat 8 Apr 2023 11.00 BST) Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2023/apr/08/simon-armitage-poet-laureate-radical-roots-rock-star-dreams

[9] Simon Armitage ‘The Song Thrush and The Mountain Ash’ in Armitage (2023: 81f.)

[10] Simon Armitage ‘We’ll Sing’ in ibid: 83

[11] Simon Armitage ‘A Few Facts in Reverse Order’ in ibid: 3f.

[12] Simon Hattenstone op.cit.

[13] In Armitage op.cit: 11f.

[14] In ibid: 135f.

[15] Ibid: 156

2 thoughts on “‘But they seem to work, accompanied by an ensemble of silence’. This blog reflects on the published song lyric as part of the ‘repertoire’ of an oral poet. It focuses on Simon Armitage (2023) ‘Never Good with Horses: Assembled Lyrics’. and on seeing him read, with @JustinCurley4 at The Queens Hall.”