‘The leaves of the plane trees were turning, and made faint dry rustling sounds when a breeze passed through them. Strafford found himself longing for the dense, drooping heaviness of summer foliage‘.[1] Reflecting on John Banville’s (2023) ‘The Lock-Up’ London, Faber.

Book Cover

When novelists you like start writing novels in a serial form, it takes a brave (or perhaps) a foolish reader to predict the next, let alone to predict the rationale of a proposed quartet of novels. Be that as it may I still said in my blog on his last novel dealing with the detectives Hackett and Strafford, and the grim forensic pathologist, Quirke, April in Spain that: ‘it seems that this novel is the Spring novel, following Winter’s novel with the appropriate name of Snow, in a possible quartet of novels based on the seasons, but of this later’. And later in the same blog I did indeed say:

Banville has, in this novel, now done ‘Spring’ and I predict that his next novel will feature Phoebe and St. John leading the way to a new pairing as detectives in a summer setting. And why not? Banville is an immensely accomplished planner of novel sequences.[2]

Given the apparent certainty in my paragraph, one might imagine that I would be deeply humbled by the fact that far from being a novel of ‘Summer’, Banville sets this one in Autumn, indeed starting specifically, once the story returns from a dark excursus in Bavaria in the April immediately after the end of the Second World War in Chapter 1, to Dublin twelve years later on a ‘day in Late September’. The German industrialist living in rural County Wicklow who will become a major reference point of the novel at one point begins to discourse, before stopped by the detective Strafford’s return to the inquisitorial reason for the his visit to him, with a pathologist in tow, on the weather pertinent to ‘September in Ireland –‘.[3] The seasonal characteristics of September so dominate the telling of the novel’s events, no-one would doubt that this novel is triumphantly, in the despite of my predictions, a novel of Autumn not Summer. And this setting is emphasised in the external landscapes: Strafford and Quirke pass Wicklow’s ‘high flat moors in thin autumn sunshine’, where ‘heather was still a rich deep shade of purple against the turf-brown bog’, in the city when fog clears there is ‘’tawny autumn sunshine’. The effects on setting, and mood, get described, as if in full embrace of the pathetic fallacy, in the colour effects of autumn too that presage human emotions about the end of things in time, dominating even in the moment where Strafford first begins his sexual affair with Phoebe, as he lays in bed following Phoebe’s departure from it, the dynamic effects of an autumn wind are revealed in sound and colour suggestions;

the massed leaves heaved and thrashed. They had taken on autumn’s grey-green pallor. Some were already brown, and soon they would all turn and begin to fall. The foliage of these trees seemed longer lasting than that of others elsewhere.[4]

Alan Massie reviewing Banville in The Scotsman believes I think that these effects are just set-piece elements of a fine writer, saying: ‘Banville is always good on weather, characters and set-pieces’.[5] But surely there is more to this writing than a stylistic riff in a novelist’s repertoire of set-pieces. Seasons matter in the sequence of serial novels and though it may have cheered me that though my prediction was wrong (but then being wrong, at least as far as ideas alone are concerned, harms no-one if the person admit to it and change their views) the prose’s associations herein seem as rooted in the traditions of poetry as I thought them in April in Spain. For surely that wind was the same one noticed by Shelley in Ode to The West Wind:

O wild West Wind, thou breath of Autumn’s being,

Thou, from whose unseen presence the leaves dead

Are driven, like ghosts from an enchanter fleeing,

Yellow, and black, and pale, and hectic red,

Pestilence-stricken multitudes: …[6]

At least this seems the case earlier in the novel when Strafford visits the grand Protestant university, his Alma Mater that also welcomed Jews as another religious minority in independent Catholic Ireland, Trinity College, in search of clues about the dead Jewish academic researcher onto the Irish Jewish diaspora whose fate is the fact that initiates the novel’s progression. Passing through the ‘vaulted porch’ of its ‘stone archway’ the seasonal weather in Front Square seems intensely Shelleyan in effects of colour and effect:

The wind was still blowing hard, and dead leaves skittered over the cobbles, making a scraping sound. The leaves were fire-red, dark gold, umber. Strafford felt a twinge of bittersweet nostalgia for a time in his life he had not particularly enjoyed.[7]

Here, as in examples above, the seasons and their weather characteristics, bear emotional weight in the eyes of the characters who sense them. Of course in a detective thriller death is both a significant and common event, for it defines the genre, but a sense of what is ‘hard’ and insistent about the winds of change and the hectic mix of colours have the kind of Romantic ring that Shelley’s poem has in comparing ‘leaves dead’ to the masses who flee from an unfair lot akin to magical enthralment or sickness. I will have more to say about the oppressed – the many not the few so often the burden of Shelley’s political poetry (notably the Masque of Anarchy) but first (since self will out) I want to make an end to the blogger’s self-affirmation to show that this novel which follows up a novel about spring does so not by one of summer as I predicted but of autumn. To do so we need to look at this beautiful piece from the novel where Strafford’s experience of cognition, sense and emotion about time is discussed through discourse on the passage of the seasons:

The leaves of the plane trees were turning, and made faint dry rustling sounds when a breeze passed through them. Strafford found himself longing for the dense, drooping heaviness of summer foliage What was that little Yeats poem?

THROUGH winter-time we call on spring,

And through the spring on summer call,

And when something something ring

Declare that winter’s best of all.[8]

There are reasons to seek out the original Yeats poem from this citation other than the ‘something something’ which substitutes for Strafford’s memory lapse about the poem. Those words are lost but are not themselves significant I think, unless ‘abounding hedges’ suggest more to other readers than it does to myself. Those reasons are clear if we read Yeats’ The Wheel (see it in full in footnote 8) for this a poem about how being a human plays itself against the cyclical motion of the wheel of time (the seasons of course). The poem roots the relationship of humans to time through emotional cognitions such as expectations and longings to the inevitability of death, and perhaps even a death-wish to end the anxiety of life in time: the blood’s ‘longing for the tomb’. It is intense emotion, equivalent to the obsession with escaping life-stress (even eustress) that sends us from spring straight to autumn and the presage of winter again in our apprehension of and about time’s passage.

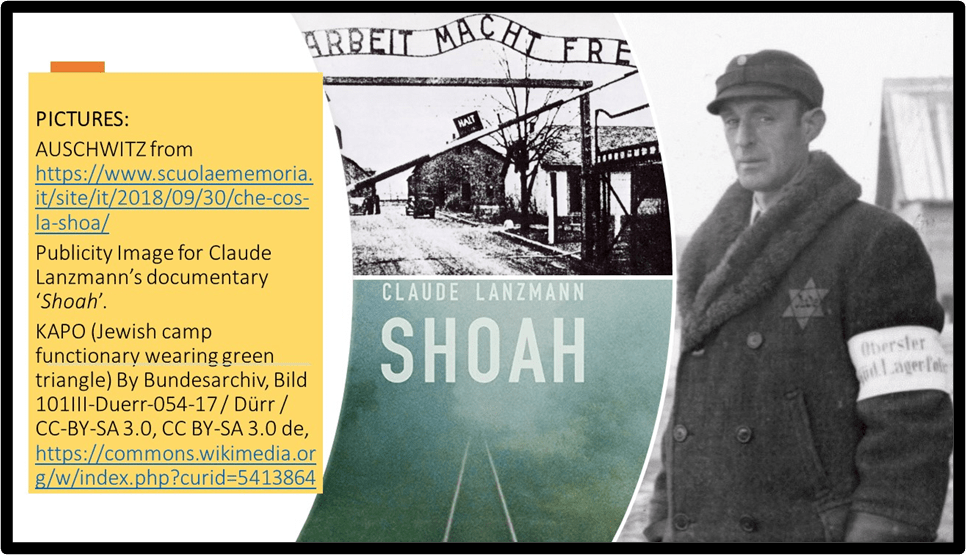

However, there are other issues relating to the echo of Shelley in the autumnal sections of this book, that I think resurrect, if for a purpose not exactly like Shelley’s political commitment to ‘the many’ not ‘the few’ to indicate the movements of masses in the geopolitics that underlies this novel, especially the Irish Jewish diaspora, which is the subject of Rosa’s research before her murder, and the role of the many sub-references to Zionism during the period leading to and after the second World War. I will later expand my argument to show how this concern with oppression, relative to Jewish people, has analogies with the treatment of queer sexuality in this book. After all, we are never, in this novel able to forget that in its underlying characters (ones admittedly never brought to surface clarity) are repressed queer men on the one hand, like Frank/Franz Kessler (and the oft remembered Terry Tice), and, on the other, the Jews who either fled or became victims of the Shoah (the novel takes pains to point out the term Holocaust is a word of a guilt-ridden but still oppressive culture not from the culture of the oppressed Jewish persons). Another group of Jews in this are that small minority (for they are represented or misrepresented in this novel) who colluded with Nazi oppression at its worst. This is shown in the representation (through the character Theodore (or Teddy) Katz, the person who is called only ‘the Jew’ or ‘the kapo’ in the retrospective chapter on Kessler’s past which is Chapter12 of the novel (a kapo was a Jew who served in the concentration camps under the German administration – whom perhaps this novel stereotypes for Primo Levi was one such).

I tried to deal with Banville’s attempts to understand the effects of oppression on character in his novel April in Spain in my last blog, but I think The Lock-Up takes this further, for the title refers not only to the location in Dublin (a small garage-space) where Rosa’s body was found and used in her murder buy gassing but to the incarceration and mass murder of the Jews of the Shoah> It also refers to the repressed secretiveness that Banville finds in the oppressed, not as a endogenous character trait but the creation of the exogenous factors which are the machinery of oppression. Here is what I said in my last blog:

What have we in this novel? Given the fact that younger peers of Banville as a novelist – novelists like Colm Tóibín and Sebastian Barry, perhaps for different reasons, have worked hard to make some of the shadier oppressions of Ireland and Europe’s past more rich and less riddled with predominant stereotypes, I have to admit that it is difficult to say the same of Banville. The past he brings back to life is scarred by an unredeemed set of stereotypical queer and Jewish characters (though surely Quirke’s wife the Jewish Austrian Evelyn, whose family survives the Holocaust, is an exception). It feels harmful to have the main go-between between corrupt government and murderous gangster underworld, that includes terry Tice, is constantly referred to as ‘Jew boy’. Phoebe’s discarded boyfriend, of course, Paul Viertel, is also a Jew and this fact is made to count. Some of this feels anti-Semitic, whatever Banville’s intention was.[9]

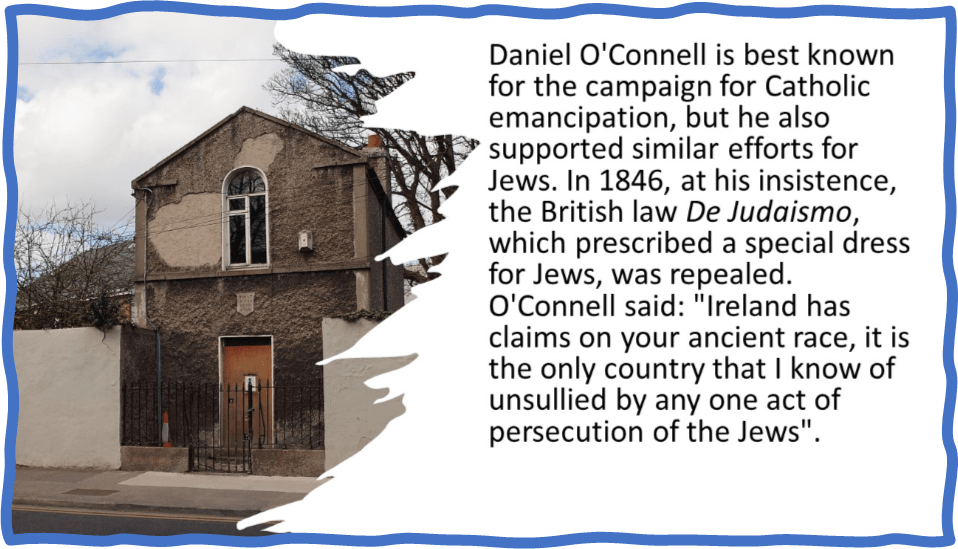

One of the side effects of a novel by Banville (more central in the novels he himself sees as literary) is the mysterious cloud of unknowing that surrounds any one character’s attempt to understand another in each of its sub-plots are children and fathers (and husbands and wives) who neither understand, nor try to do so, by talking to understand each other). This is still the case of Frank at the end of his novel who clearly has a history of oppression by father and fatherland as a queer man and son. But we learn in this novel that this is true of characters like David Sinclair too, who appeared in the very first Benjamin Black novel focused on the life of pathologist Dr. Quirke, and whose relevance in this one is that he is a Jew who has left Ireland for Israel. Quirke realises that he barely knew Sinclair (and hence neither would we in the early novels. Though that is attributed to Sinclair being ‘private, to the point of secretiveness’, suddenly this supposed character trait is seen as caused by possible persecution of Jews in Catholic Ireland, an issue that remains only a possibility in part because entitled classes in the new Catholic Ireland felt no reason to be wise (in thought and/or memory) about the life-stories and history of Jews, even Irish Jews. The life-stories and history of … Irish Jews is indeed the subject of the research work of Rosa, the Jewish academic researcher killed in order to become the motivator of this novel’s events:

There had been riots – a pogrom – here in the early years of the century. Or was that Limerick? He couldn’t remember. He never understood why the Jews had been persecuted down the ages. …

It occurred to him suddenly, with a jolt, that Sinclair might have thought him an anti-Semite. That would account for the guardedness, the sarcasm, the occasional flashes of resentment and bitterness, over the years.[10]

Ballybough Jewish Cemetery (founded 1718) gate lodge in 2020 By Smirkybec – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=88947281 Citation from Wikipedia regarding views of Irish revolutionaries.

The self-questioning by Quirke of the possibility that he could be anti-Semitic without even realising it is interesting to me because just as ignorance of a history of persecution might explain the ‘secretiveness’ we thought of as constitutional in Sinclair. Such histories provide an aetiology in oppression, so is the case with Frank Kessler, whom Rosa the modern atheistic Jewish researcher knew to be queer, though everyone else invents stories of him as the jilted heterosexual lover, who might have killed her, of Rosa. As a result, this is one of the reasons that the true murderer of Rosa goes free, at the end of this novel at least. But this diversion into the novel’s rather brilliant side-effects of analysing the role of oppression in the creation of stereotypes and cover personalities for the oppressed lies in the novel’s deep trawl into the effects of the relationship of all human beings to time, and as we shall see the apprehension of death as a model for endings in otherwise ongoing time.

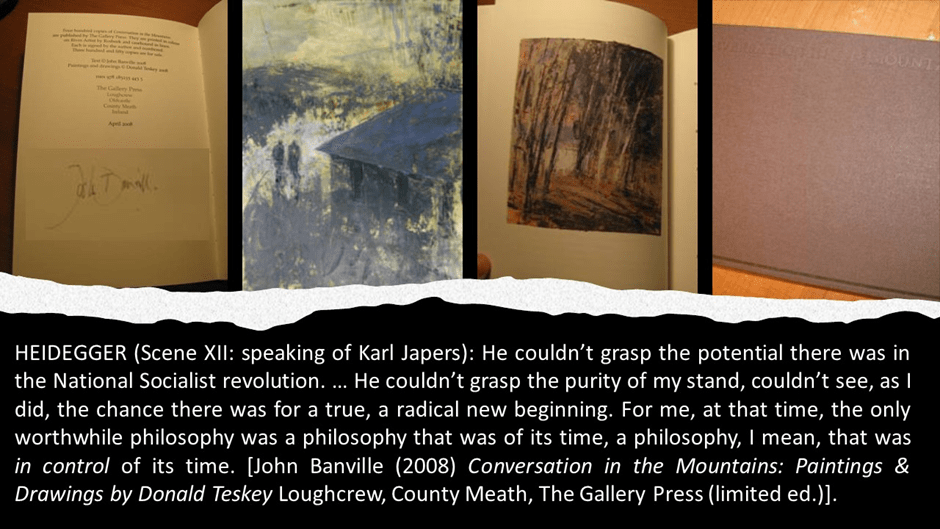

This idea is orchestrated into the novel too through references to Martin Heidegger and the phenomenological philosophy in his great book Being and Time. For Heidegger’s personal and philosophical ideas about Being-in-Time were also evoked and challenged through the experience of anti-Semitism in Fascist Germany. This is a theme Banville dealt with in a radio play of 2006, Todtnauberg (the location of Heidegger’s hut in the mountains and the name of a poem by Paul Celan recording his visit there) published in 2008 as Conversation in the Mountains). This play was published alongside reproductions of beautiful drawings and paintings by Donald Teskey, which is a jewel of my book collection).

Illustrations available in: https://marksarvas.blogs.com/elegvar/2008/07/conversation-in.htmlBa

Asked by Mark Sarvas in 2008, regarding Conversation in the Mountains why German writing fascinates Banville said to him:

German literature, including philosophy, has been an abiding interest with me since I was a teenager. I find it exciting and challenging and, I suppose, a fascination since, having been born in 1945, I grew up in the long, ashen shadow of the concentration camps. How could such a culture end in such catastrophe? I’m still reading, still trying to find out.[11]

As a result of his reading and translations from German literature, Banville seems to have grasped and wanted to communicate this grasp that Heidegger was once not only keen to render the ontology of human values as things that existed relative to temporal experience but to control temporal experience (the mass and individual psychology of expectations, anticipations, wishes, hopes and their basis in memory systems) in a way that ensured the world was renewed for its own time and not in hoc to its faulty historical recollections. Speaking of former friend and colleague, the radical existential phenomenologist Karl Jaspers, Banville’s Heidegger says in Scene IX to Celan:

He couldn’t grasp the potential there was in the National Socialist revolution. … He couldn’t grasp the purity of my stand, couldn’t see, as I did, the chance there was for a true, a radical new beginning. For me, at that time, the only worthwhile philosophy was a philosophy that was of its time, a philosophy, I mean, that was in control of its time.[12]

Being in control of time is precisely what defines the vicissitudes of this thing we call human life. Banville renders these vicissitudes well in quite diverse ways in characters in Banville’s serial novels like Hackett, Strafford, and Quirke, in particular. For none of these is in control of time, memory, or anticipations, indeed the reverse is true – the effects of time play on their psychology, particularly in their apprehension of the meaning of death and other endings, catastrophic or otherwise. It is precisely what we see when, ‘Strafford found himself longing for the dense, drooping heaviness of summer foliage.’ Strafford’s relationship to time in this sentence is one in which he is the passive rather than active agent of feelings about passing time. Even his incomplete memory of ‘that little Yeats poem’, The Wheel, leaves out the crucial point, that death wishes can be so potent over human life that they can hurry from spring to autumn’s expectation of winter and bypass summer.

Through winter-time we call on spring,

And through the spring on summer call,

And when abounding hedges ring

Declare that winter’s best of all;

And after that there’s nothing good

Because the spring-time has not come –

Nor know that what disturbs our blood

Is but its longing for the tomb.

The German entrepreneur, Kessler, who, as we learn, was once the Commandant of a concentration camp, and whom we saw escape the Allied invasion of Germany via the border of Bavaria to the Italian Alto Adige with its mixed population of Italian and German (60/40% ratio) speakers, and who is said to be involved in arms’ deals with Mossad for the Israeli State lives in Wicklow because he is a ‘a man of the mountains’. His ‘spiritual home’, though born in Munich, he says is the Bavarian Alps where he has ‘a house’, going to elaborate on that habitation as ‘not much more than a Hütte, you know – a hut’.

Quirke like Banville sees parallels with Heidegger in those facts though so would any reader of Banville aware of his full oeuvre including the translations from the German of Kleist. Kessler retorts:

“Ah yes, you know of Heidegger.” Quirke could see himself being reassessed. “he has his hut – architect-designed, mind you – in Todtnauberg, in the Schwarzwald, the Black Forest.” He paused. “An interesting case, the Herr Professor.”

“Yes,” Quirke said, “he hasn’t recanted. In fact, I’m told he never resigned from the party.”

“A man of principle. But the wrong principles, of course. …”[13]

If this primarily takes up the problem of the meaning of philosophical fascism, it does so in a similar manner to Banville’s Heidegger character in Conversation in the Mountains. And Quirke elicits this conversation precisely to get to the bottom of the Kessler links to both the murdered Rosa as an Irish Jew and Kessler’s own business interests in Israel. To Strafford on leaving the house, Quirke insists he mentioned the philosopher not because he read him (because he claims he hasn’t) but in order to impress Kessler in the hope of eliciting information. Strafford however clearly has read Heidegger, though he does not say so overtly. He would not say overtly because he has learned that Quirke’s knowledge is little more than superficial and therefore irrelevant. Yet it is Strafford who eventually detects why Heidegger’s issues about the control of time matter to the Kesslers.

It is Strafford who learns from Frank Kessler that Frank has murdered his father for being involved in the political murder of a Jewish journalist who was about to expose his father’s role in ‘supplying Israel with important components for the manufacture of an atomic bomb’. The analogy to Heidegger, especially to “Die Hütte”, Frank reveals, was merely a false image used by his father to disguise that he, like Hitler was a sham leader pretending to finesse of origin, trying to be in control of historical time just as Hitler was on a larger stage. Kessler was, his son says, “…born in a Munch slum. As a child he was sent to work for nothing for an uncle, up in the mountains. He lived in a shed, like one of the farm animals”.[14]

From my description this will see a truly reductive use of the Heidegger myth one might think, But I’d disagree, for the Heidegger that matters here is the one in Banville’s early writing and thinking is used to show how people build defensive personalities that hide the truth of their oppressed circumstances as we shall see in many of the novel’s Jewish characters and, I’ll insist later, his marginalised queer characters. The marginalised are forced by social conventions, unless they take charge of their own past, present and future to live life constrained by an image imposed upon their enemies – enemies we might call anti-Semitic and the homophobic, in the particular cases of oppression worked through in this novel. Experience of oppression distorts the present and future for those who are oppressed because they must build ways of surviving that seem counter-intuitive and work with people in ways historically CONTROLLED by their oppressors until they can be in control of their own history, or being-in-time.

A version of this gaining control is paradoxically given to the old man Kessler, the former Nazi, to articulate, on behalf of a world order in which Israel is fighting for a place. Israel, he argues, contains in its a tough and pragmatic ‘new kind of Jew’ who have ‘left the shetl far behind’. The interesting thing here though is that Kessler compares Israel as a country and Jewishness to Ireland as a country and Irishness.

Israel, you know, is a strange – how do you say? – a strange phenomenon. It’s not unlike Ireland, I think. Yours too is a young country, and your people too have a history of oppression and suffering. I have read about this. Oliver Cromwell was your Adolf Hitler, I think?[15]

In both cases oppressor languages, as well as other cognitive tools, become the language of the oppressed and sometimes thence a means to self-oppression and the oppression of others. Young countries and cultures find ways of working with tools, such as language that is still owned, or so it might seem, by the oppressor, (English in the case of the Irish novelist). This is what happens to Irish characters who constantly must ensure that they are not being collusive with those who want to destroy them in their own self-destruction. The same kinds of contradiction which will not allow us to know truly where old Kessler has indeed changed are what feeds Irish politics, wherein: as Yeats put it:

… everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.[16]

It is my wont as a blogger however, always to return to how what a novelist attempts to do in their whole novel reflects on the portrayal of queer characters and queerness, perhaps especially in a novelist so marked heteronormative in his descriptions of sexual encounters and wishes, especially Quirke (in this novel more than any other). Let’s look at how I saw this issue in April in Spain in my last blog:

The word ‘queer’ in this novel is liberally used – once only just to mean ‘ill’ – but always with negative connotation. Even when it is used to mean ‘ill’, it is used of Terry Tice in the context of his attractiveness to old queer men, and in this case Percy Antrobus, who is plying him with the very drink that left ‘him feeling queer for days’. His attractiveness to ‘old buggers’ makes Terry think ‘what it is about him’ that does that. But he accepts being kept by Percy nevertheless and a rather lack-lustre sexual relationship, which is made anything but attractive. Percy’s mouth for instance is described as an anus, for obvious reasons: ‘pursed into a crimped little circle that looked less like a mouth than a you-know-what’ and a ‘little pink puckered hole’. The corrupt government administrator, Ned Gallagher, too, who commissions April’s murder by Tice, if indirectly through the (queer] ‘Jew boy’, is subject to corrupt ministers because ‘the Guards had caught him in the gents’ convenience …, on his knees in front of a young lad with his trousers around his ankles’. [17]

In The Lock-Up the suggestion that someone we thought we knew but actually did not, as is the case of David Sinclair for Phoebe,[18] also holds potential for the identification of the person being a closeted gay person. For instance WHAT exactly Kessler knows about his son Franz is continually hinted but also disguised in his silent accusation of his son as a ‘weakling’: ‘The man loved his son but knew him for a weakling. He had tried to toughen him up but nothing had worked, not lectures, not mockery, not beatings, even. The creature was more like a girl than a boy’.[19] Elsewhere Frank, in confessing the murder of his father but not of Rosa, recalls the terminology used to belittle him in the German terms for ‘weakling’ and ‘girl’:

Always he despised me, always pushed me to the side. “Mein kleiner Schwächling,” he used to say to people. Look at him, my little weakling, mein kleines Mädchen. He could never accept me as I am.[20]

Above I said: ‘someone we thought we knew but actually did not, … also holds potential for the identification of the person being a closeted gay person’. There is no better example than Frank’s sudden identification of Strafford as a queer man like himself, oppressed by a father in exactly the same way:

“I knew it!” Kessler exclaimed and his grip on Strafford’s arm tightened convulsively. “I knew we were brothers, of a kind, kind of – Wie heißt das? – of a spiritual kind. … Don’t you feel it too? Surely you must.”

Strafford soon apprises Frank that he ‘came to the wrong person’. Yet Banville never makes such material overt. Though there is pathos in Frank’s later confession to Strafford before his suicide: ‘“I could have loved you,” Kessler said, still with his back turned, and so softly that Strafford wasn’t sure he heard correctly. “But it’s too late.”’ [21]

But is there more than pathos in this half-hearing things one might or might not wish to hear consciously or unconsciously. Few readers will remember a passage of Strafford’s memories from his past earlier in the novel where the same suggestions and denials are in operation around him, but I found myself taking a note, though the incident relates to the strange relationship, often expressed in violence, with Quirke:

When Strafford was in his final year at school, a boy in his class had developed a strange obsession with him. …

It must have been a homosexual crush, probably unconscious, that Robinson had developed for him, Strafford thought now, though it had not occurred to him at the time. The boy was drawn to him by a seemingly irresistible compulsion. … It was like being pursued by a hapless, tormented lover, one whose love, by being spurned, had transformed itself into a kind of hatred.[22]

So much of love is a kind of fugue state in this novel – not least in its constant return to Sir Thomas Wyatt’s lyric ‘They flee from me’ – but much more is about what is repressed, contained, enclosed, secret and locked-up. The image of a polar bear’s enclosure haunts Strafford, together with his memory that ‘if he could he would open the cages and let all the animals’ in the zoo ‘escape’.[23] He sees Quirke ‘clasped in his own pained embrace’.[24] Some of the material around this is incredibly moving and blurs the difference between Banville’s detective and literary fiction with its visceral concern on each side with death, loss, and pain. But one can read the detective fiction lightly and, for me, negligently, but why not. It passes the time, even if we get no nearer to being in control of it, with or without the help of Martin Heidegger.

Do read the novel.

All the best,

Steve

There are other blogs on this series at these links:

[1] John Banville’s (2023: 147) ‘The Lock-Up’ London, Faber.

[2] From : https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/11/16/april-he-said-the-name-giving-phoebe-a-start-until-she-realised-it-was-the-month-and-not-her-missing-friend-he-was-speaking-of-an-undependable-time-of-year/

[3] John Banville (2023: 3 & 21, 129). Respectively the first reference justifies the Bavarian seasonal setting in April, the second and third the Dublin and surrounding County Wicklow setting in September.

[4] Ibid: 120, 117, 265 respectively.

[5] Alan Massie (2023) ‘Book review: The Lock-Up’ [23rd Mar 2023, 14:38 BST] Available at: https://www.scotsman.com/arts-and-culture/books/book-review-the-lock-up-by-john-banville-4076776

[6] P.B. Shelley Ode to The West Wind Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/45134/ode-to-the-west-wind

[7] John Banville 2023 op.cit: 66

[8] ibid: 147f. The poem is Yeats’ The Wheel: ‘Through winter-time we call on spring, / And through the spring on summer call, / And when abounding hedges ring / Declare that winter’s best of all; / And after that there’s nothing good / Because the spring-time has not come – / Nor know that what disturbs our blood / Is but its longing for the tomb’ (see: http://www.online-literature.com/yeats/811/).

[9] https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/11/16/april-he-said-the-name-giving-phoebe-a-start-until-she-realised-it-was-the-month-and-not-her-missing-friend-he-was-speaking-of-an-undependable-time-of-year/

[10] Ibid: 159

[11] Mark Sarvas (2008) ‘CONVERSATION IN THE MOUNTAINS – A Brief Q&A With John Banville’ in The Elegant Variation literary weblog [JULY 01, 2008]. Available at: https://marksarvas.blogs.com/elegvar/2008/07/conversation-in.html

[12] John Banville (2008) Conversation in the Mountains: Paintings & Drawings by Donald Teskey Loughcrew, County Meath, The Gallery Press (limited ed.).

[13] Ibid: 130f.

[14] Ibid: 312f.

[15] Ibid: 139

[16] W.B. Yeats The Second Coming. Available at: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/43290/the-second-coming

[17] https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/11/16/april-he-said-the-name-giving-phoebe-a-start-until-she-realised-it-was-the-month-and-not-her-missing-friend-he-was-speaking-of-an-undependable-time-of-year/

[18] John Banville 2023 op.cit: 149

[19] Ibid: 199

[20] Ibid: 310

[21] Ibid: 314ff.

[22] Ibid: 270

[23] Ibid: 48

[24] Ibid; 59

3 thoughts on “‘The leaves of the plane trees were turning, and made faint dry rustling sounds when a breeze passed through them. Strafford found himself longing for the dense, drooping heaviness of summer foliage‘. Reflecting on John Banville’s (2023) ‘The Lock-Up’.”