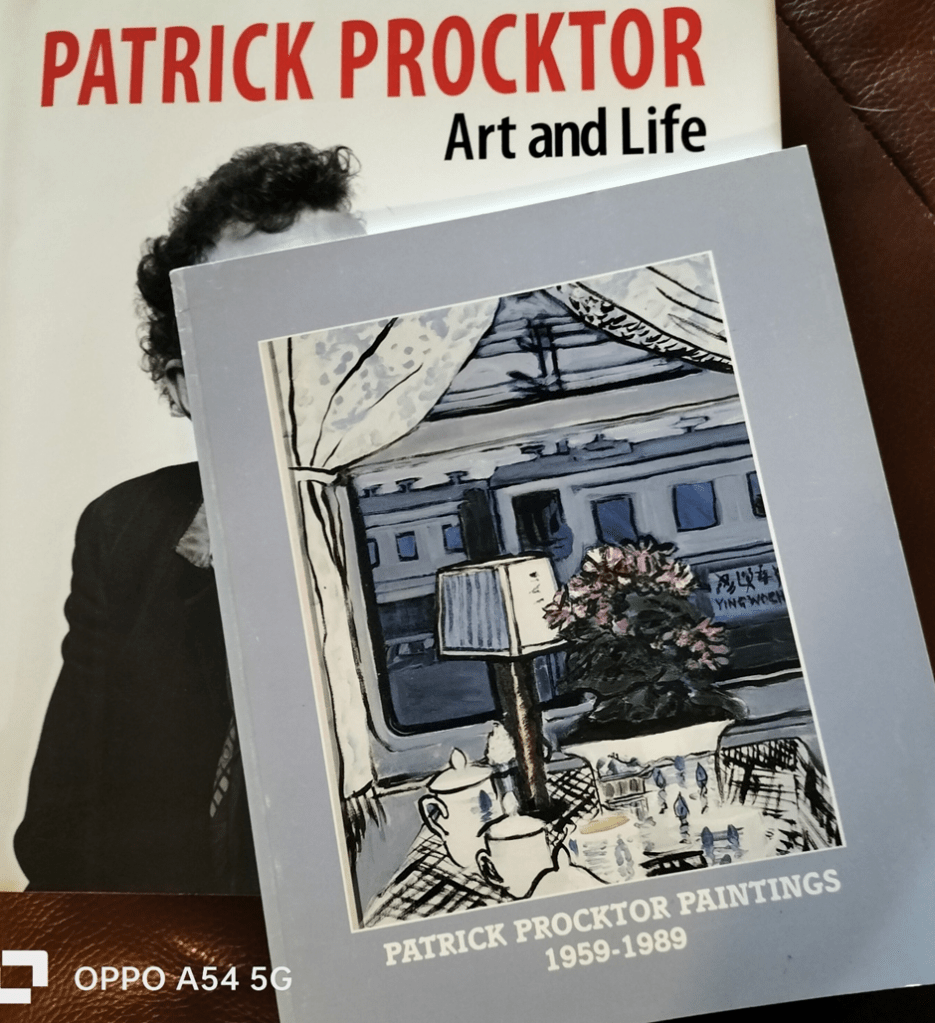

The joy of collecting books is the chance find that opens doors that that were not even left ajar in expectation of those unknown treasures. This blog reflects on finding a catalogue for an exhibition of Patrick Procktor’s paintings from 1989. In the light of an earlier blog on Ian Massey’s (2010) fine biography entitled ‘Patrick Procktor: Art and Life’ Norwich, Unicorn Press, I reflect on Michael Nixon’s (1989) Patrick Procktor Paintings 1959 – 1989 Newtown & Welshpool, Powys, Wales, Oriel 31, Davies Memorial Gallery.

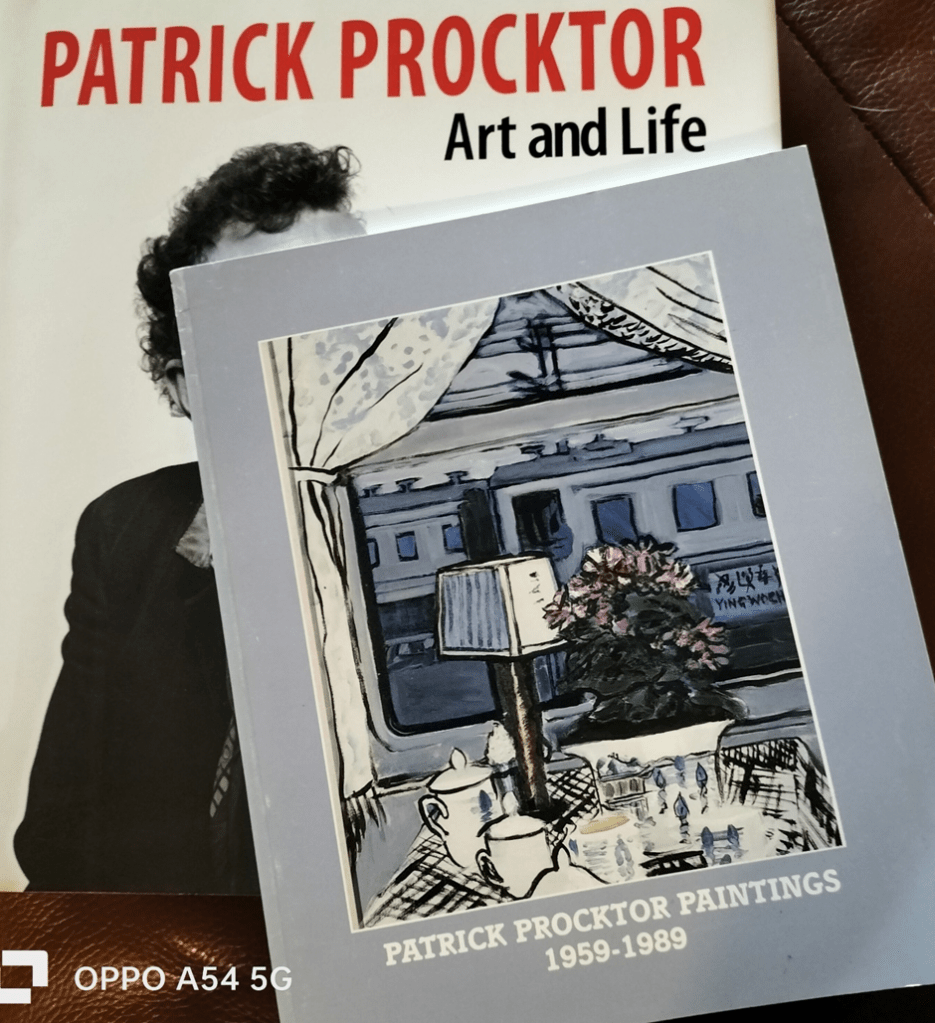

The cover of my copies of the catalogue reflected upon & the book by Ian Massey. The painting reproduced on the cover is Soft Class (1981)

NOTE: For the original blog on Ian Massey’s biography use this link. And for another blog on Ian Massey’s more recent work on queer art history (Queer St. Ives and Other Stories published 2022) use this link.

This blog is one of others where I set out a case based on a recent acquisition for the joy that can come from that pastime, especially in what I consider as my late phase as a book-collector. Book collecting isn’t after all that savoury a business. It is bogged down by two forms of collecting that were both earlier phases of collecting for me. When I first collected I looked I think for objects which impressed by the scarcity in the market. This was no doubt synonymous to collecting those book-shaped objects singled out by their possible exchange value – what they might fetch if, preferably, bought cheap from some unwitting seller and later, sometimes immediately for dealers in such items in a market inhabited by buyers who were cognoscenti. In those days I sought rare editions of both well-known authors and some less well-known, and though exchange value in fact determined desirability, such value was rarely realised, since I imagined their value to me to inhere in some other evaluative system than monetary ones. I was never a very successful selector (for I overestimated I think the value of some books which, thought undoubtably scarce, were of interest to very few indeed even as beautiful objects of bookcraft. I think even the remnant of such a collection has now gone – most often gifted to the same cognoscenti who might have bought them had I been inclined to seek a profit on my original interests.

A later phase involved collections of modern writers – single authors whose work in first impressions of the first edition I must have as complete as possible. Some strains of this show, though I have abandoned some authors, usually at a loss since I often bought when they were popularly sought and disbursed when less so. The reputation of twentieth-century authors fluctuate heavily and monetary returns come on very few – not even for the scarce early ones. Of course to some authors I remain loyal – to Iris Murdoch, A.S. Byatt, Kazuo Ishiguro. Some living authors, including the last two named, I still collect as they publish regardless of value – Jenni Fagan, Séan Hewitt and Andrew McMillan (though monetary value may accrue to them – perhaps I just don’t care), for instance, though here I have a bias for queer writers – latterly even for twentieth century ones now forgotten like Ernest Frost or ones thought to write for more popular markets like Patrick Gale.

But this is not the joyful part of collecting, though it is at the level of reading those authors and, for some, blogging on them. The joyful bit is in finding book curiosities – often of no value, monetarily speaking. The last comment may not apply to the small catalogue of Procktor paintings I look at below for when I looked for his biography, in pursuit of its pleasing writer on queer art history, Ian Massey, copies were selling in the market, then, for upwards of £100. Of course such values fluctuate massively so I don’t consult them. Other books have such limited financial value that I bought some for as little as £1 – the one in this blog (use link) for instance: a blog I called: Being a lover of second-hand books. An example of what it might mean to own a book.

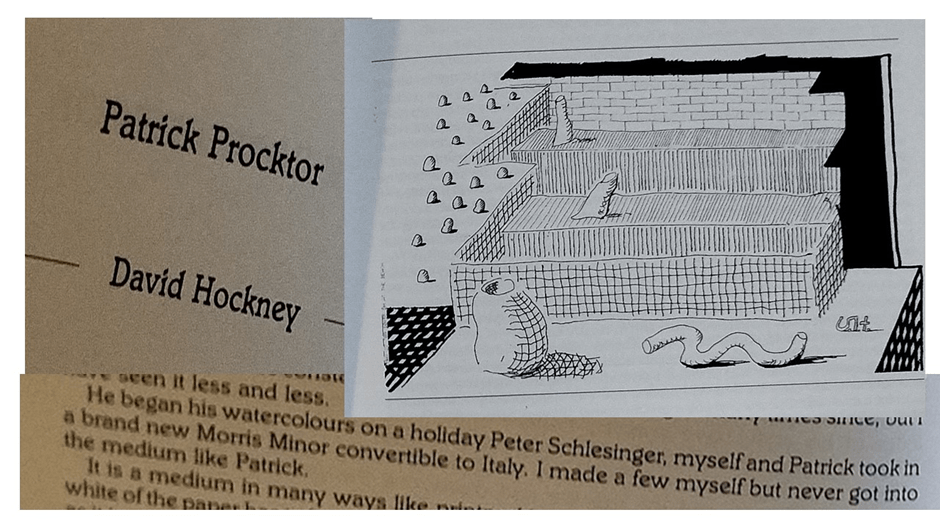

The current blog relates to a pamphlet like catalogue for a selective retrospective of Procktor’s paintings held having started with its originating galleries in Wales toured (in 1989 and 1990) Colchester, Jarrow, Kendal, and Stoke-on-Trent with the aim of showing, in curator Michael Nixon’s words that the artist’s ‘stylishness and elegance’ (in an ‘inelegant age’) has a ‘dedication to wrest beauty from life’. In words that almost typify the queer standing apart from conventionally popular in life, Nixon says: ‘Stylishness and elegance in the popular mind are often synonymous, but this exhibition sets out to show the underlying seriousness of Patrick’s approach to painting and beauty’.[1] To help in this endeavour the catalogue also boasts a preface on Procktor by David Hockney which hints with the decline in their closeness in practice at the change too in his image as one who ‘positively seemed to be in charge’.[2]

The Hockney preface

To me now there seems a kind of code that points to Procktor as a queer artist (stylishness and elegance being usually not the preserve of heteronormative males) and to his decline into alcoholism that Ian Massey has clarified in the artist’s posthumous biography, but we can never be sure of this given the fact that class is often the signified in talk of superior practitioners of life as an art in the service of beauty. And though Hockney has a stress on the medium of watercolour in Procktor’s art, only 26 of the works shown were watercolours, 30 oils and 5 drawings. Bryan Robertson, Director of the Whitechapel Gallery, also provides an introduction but the emphasis is on developmental growth in Procktor’s art that stands against dominant current trends which Robertson names ‘post-modern stylistic games’ and ‘neo-conservatism’.

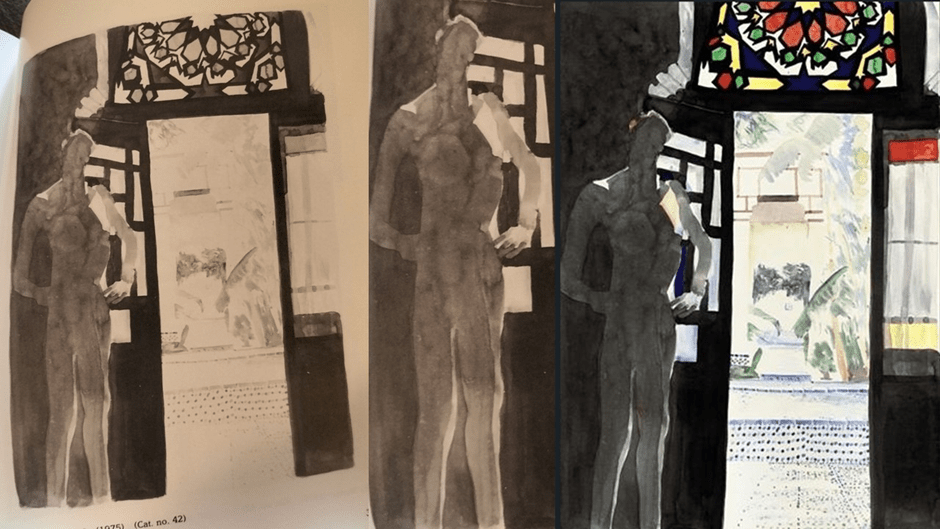

In fact, whatever thesis one might be attracted to this little book attracts for other reasons for me, for as text of ideas there is nothing here that is not considerably better dealt with the Ian Massey magisterial biography. But though the illustration is much richer too in Massey, this little catalogue is a beautiful addition to a Procktor book collection, even despite the standards of the period that allowed for a high proportion of black and white illustrations of works that depended on their conveyance of effect through colour. However, without it I would never have known of the beautiful 1975 work Self-portrait in Fez, which is a study of how colour is seen or imposed (by stained glass for instance) on the perceived world of form perceived through a medium of deceptive plays of light and shade, the perceptive and light differences between insides and outsides as seen from the former. This nude is shaded not only perceptually but as a picture of a complexly apprehended look at one’s own sexuality from the point of view of Procktor as both a queer man of his time and as queer even in the most contemporary of senses – a man not defined by conventional forms and binaries but in the range of effects created by their interaction.

Self-Portrait in Fez (1975) as in Nixon op.cit: 37 (Cat. 42) and colour reproduction from cropped webpage: https://www.wikiart.org/en/patrick-procktor/self-portrait-in-fez-1970

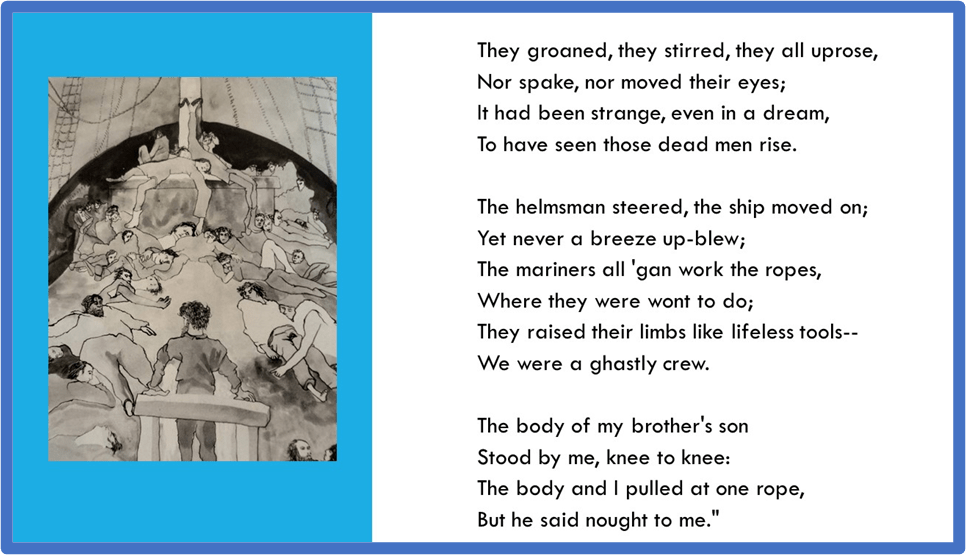

And other painting and illustrations struck me. Massey has explained beautifully and simply the motivation of Procktor(and his collaborator in this form Charles Newington) in attempting to rival as well as honour Gustave Doré’s illustrations to Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. Together they produced a series of 1976 etchings, with the two beautiful two-colour aquatint ones illustrated in the Massey book, which also describes the others as 8 ‘direct extemporisations’.[3] But what are direct extemporisations? In music, they involve playing a known piece without time for preparation (ex tempore) whilst in visual art they seem to involve some kind of metamorphosis of a known image where temporality seems less involved and may be misleading. They are a kind of ‘improvisation’ but even as such they are not as spontaneous as this makes them sound. My new little catalogue provides an example from the 8 and which I believe illustrates the waking of the dead bodies of the crew to ‘man’ the ship that will return the old mariner narrating it to continuing life. The image is a strange mix of direct copy of Doré and queer differences hard to pin down.

What immediately strikes one is the deliberate inversion of dark and light imagery and hence a refusal to use the stage-lighted effects that interest Doré, such as the apparent spotlight, aping moonlight, trained on the mast and centre deck, with its look of a planked stage. As a result the bodily contra-positioning of the crew is much more evident and played upon so that these bodies are more evident, even enlarged in physical size and light clothing, such as in the much fatter torso of the man to the left of the viewing bearded mariner. The effect is much more embodied – and live-bodied rather than dead or undead-embodied. The men seen to clasp each other much more intimately and actively than accidentally as they fell for a second time. This is a fully queer take on the poem. Other pictures are more directly sexually queer, such as the beautiful 1988 oil painting Darren’s Back.

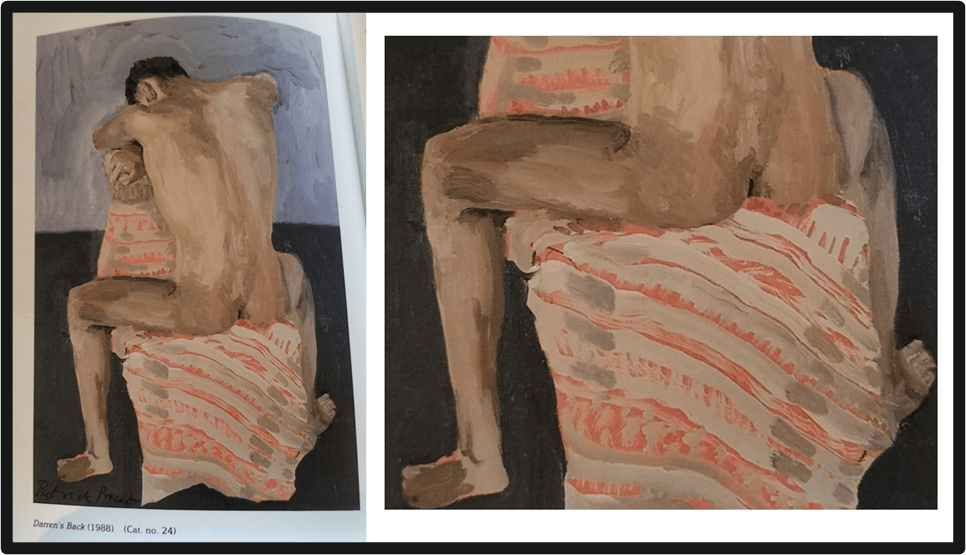

1988 oil painting Darren’s Back in Nixon op.cit: 30

This painting is queer as a portrait of Darren Etienne, ‘a friend of’ [the queer photographic artist] ‘David Gwinutt’, and as an erotic image. It uses the rucked red line images of the cloth on which Darren sits, which is a dark vermilion at this point to emphasise the line of his anus as a point of access and egress and even, given associations of the colouring here with blood, of physical skin rupture. The aim of these paintings, according to Massey’s scholarly interpretation, can be aligned with the paintings of young queer Black men in the 1930s painted by Glyn Philpot (see the link in these parentheses for my blog). As a painting the one exhibited in this catalogue surpasses the 1988 side view of Darren reproduced by Massey, although yet again both appear to show how a portrait painter of the Black nude body needs to challenge the colour palette and treatment of the male nude as a form in terms of background as well as figurative foreground aesthetic choices. Such choices are not a matter of exoticisation of the Black nude body but an evasion of such unfortunate associations under the ‘white gaze’. [4]

Hockney’s reference to his holiday with Procktor and his own lover (unacknowledged as such in this writing), Peter Schlesinger appears in this book as a set of watercolours of the shadowy phallic columns of an Egyptian temple placed alongside delicate watercolours with their own phallic appearances of the extremely good looking Peter in his swimming trunks in Luxor. These are near to each other in the catalogue and attest to a new use of light and shade in both figure painting and architectural landscape. They are a joy.

This is not a blog that makes any claims however about Procktor, just attests to the joy of still collecting new books – even from cheaper sources as is now my retired want.

All the best

Steve

[1] Michael Nixon’s ‘ Foreword’ (1989: 5) to Patrick Procktor Paintings 1959 – 1989 Newtown & Welshpool, Powys, Wales, Oriel 31, Davies Memorial Gallery.

[2] Ibid: 6

[3] Ian Massey (2010: 142f.) ‘Patrick Procktor: Art and Life’ Norwich, Unicorn Press

[4] Ibid: 172f.