The narrator, of James Kelman’s 2022 novel, God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena, Jack Proctor, a writer who identifies as working class, says of his experience as a resident writer in ‘The House of Art and Aesthetics’ in the USA: ‘I had a glorified view not just of art departments but colleges and universities, as intellectual hotbeds. When I discovered the truth the disappointment of that stayed with me and it’s with me right now’.[1] A great author summarises his disappointment with the notion of elite culture and the pretence of knowing what art is without working hard to do it.

The cover of the book and the author.

The work of James Kelman has been with me for some time though I have rarely blogged on him for I think he is a difficult novelist to translate into the terms of a commentary which is primarily literary and not about so much more than the literary. This so-much-more that Kelman evokes is about the august subject of ‘being an artist’. For Kelman ‘artist’ is a word that a writer should be proud to apply to themselves, rather than pretend to some other self-description. For artists are persons who work to make a thing called art out of basic materials proper to their particular form of artistry. Art is not a mental concept thus understood for it is the fact that it requires the artist to work on basic materials in order to facture it that defines them as artists, rather than any concept external to that activity or work. An artist is par excellence a worker or they are not an artist.Nevertheless, it remains true, Proctor (the ‘I-voice’ or first person narrator in God’s Teeth) argues, that amongst writers it is commonly the case that:

We avoid the term “artist.” How come? How come we are so wary of it – afraid even. Some are hostile? They think writers are presumptuous because we use the term “artist” and apply it to oneself how else do we make the reference?[2]

In fairness to the transparency of this novel’s purpose, in this regard at the least, we cannot do much more with these words than cite them, for they mean exactly what they say. Hence my précis of them in what follows must be treated with the same suspicion ‘working artists’ (more of them later) might be advised to use in their approach to those who merely talk about art and artists as opposed to people who make art by painting, writing or composing. Nevertheless, my précis is as follows. Art, as Jack talks about it to many audiences proffered to him through his novel, is a process of doing or working which produces something, a work of art. The art is an aspect of the work done on materials not in some transcendent nature which applies to the artwork itself independent of its making. Of course, as with every other role in the world, the artist may profess other self-definitions (some of them much more verbose), including those offered to it by institutions that claim to support and represent ART. It is these windmills of the mind and discourse, that the particular Don Quixote of this novel, Jack Proctor, sets out to tilt against; not so much as knight errant as in another quixotic (and somewhat tongue-in-cheek) self-description Proctor offers of his ‘type’. This self-description is at one point the ‘itinerant intellectual of the Gallowglas persuasion’.[3] Another more serious self-description in my view is one he gives to one of the many ‘Arts Control Officer(s)’ who try to direct his intellectual and practical peregrinations through the novel’s events: here he calls himself ‘a working artist, what ye might call a journeyman’ attempting to engage ‘what ye might call apprentices, would-be artists’.[4]

The term ‘Gallowglass persuasion’ invokes the notion of the rebellious Celtic mercenary and invoke one of the many stereotypes of the Scottish as non-normative in ideological history that Jack both confronts and sometimes is forced to reluctantly adopt, such as that in a publicity flyer written about him whilst he is in the United States ‘Jock’ the writer in Lallans. That last written representation indeed contains two false stereotypes of Scots as persons (but specifically here men, ‘Jocks’) and as a language, about which Jack fumes in bold contemporary Scots:

“Jock” but man it was totally racist. Also it was a lie. What they had written was an actual lie! … Lallans? What the hell is Lallans? I don’t even know what it is, Lallans man know what I’m talking aboot – naw, neither do I.[5]

But ‘itinerant intellectual of the Gallowglas persuasion’ is less a slur on Jack because it registers a truth of his artistic persona even in his own estimation. It is the same truth conveyed by the ‘journeyman’ typology as an emblem of Jack’s artistry. For both terms refer to work that must be paid for – the mercenary works for money of course and the term journeyman, derives from the French to indicate a man paid for his knowledge, skills, and their application in work by the day (rather than as a salary accruing to more stable (and bourgeois) working contract. Of course, the term ‘journeyman’ becomes associated in its etymological history with the medieval guild systems of acknowledged crafts and ‘mysteries’ to denote a skilled worker (as opposed to the ’labourer’); one who has survived a formal apprenticeship. This meaning, as we shall see, matters to Jack too – and is perhaps more primary than the association to payment for skilled ‘work’ though that too is important.

Why artists make art (in this novel usually discussed in terms of why writers write) is a question of motivation central to its themes. make art in order to get paid – for money or ‘dough’. This theme is central to references in the novel to the thinly disguised and lucrative Booker Prize for the novel, won by Kelman in 1994 for How Late It Was, How Late and the fact that the writer was critiqued for the use of expletives like ‘fuck’. This critical reception is referred to as the use of ‘swearie words’ in God’s Teeth, where the prize is called the Banker prize, with an obvious play on the fact that though bankers bank money (or ‘dough’) to accumulate it for their clients and themselves, they also give out ‘dough’ (currently £50, 000 in the case of the Booker) to those talented but without money to indicate how a capitalist establishment betokens success in the world in which their values dominate. Such prizes appear to validate a cynic’s suspicion that writers write primarily for money and / or social success made evident by signs of visible status (like winning prizes). And a cynic such as I invoke here in fact appears in the novel in the form of a Professor-Poet.

The ‘Professor-Poet’, who is also the Director of the University Creative Studies Programme, tells Jack that he has prepared the students by giving out ‘photocopies of the opening pages’ of his Banker Award novel. He states his reasons thus: ‘You know students Jack success and career-building. Huh! The Banker Prize Jack, it must turn a few heads? Students are students. He rubbed his hands’.[6] Deliberately satiric, this typification does not attempt nuance, although I feel personally that I have such met examples of such self-unknowing representatives of the modern ‘Art and Thought industry’. That industry is exemplified in a set of examples like the ‘backpage of the TLS, NYR, LRB, McS … and all that fucking phantasmogoric shite, debased artforms and establishment control’.[7] What the Professor-Poet stands for at base, I think, is a debased understanding of writing as the source of a fanciful prestige and less fanciful income or ‘salary’; something more socially stable that the pay of a ‘journeyman’ or the those of the ‘Gallowglas persuasion’. Indeed the Professor-Poet even uses the fact that Jack accepted dough from The Banker Prize to infer that Jack is less an artist of integrity than a hypocrite, pretending to be radical by using ‘shall we say liberal uses of the Anglo-Saxon’ (a terrible way of referring to writers who use Scottish language forms) whilst living off ‘the establishment’:

… you must find it a little ironic – as a proud Scot Jack which I know you are – attacking the so-called establishment yet more than willing to receive its rewards, and who can blame you for that Jack a rather tasty prize of how much did you say? Many many thousands, was it not, the old Banker?[8]

The Professor-Poet may display exceptionally low self-knowledge but what he exposes is a contradiction facing any and all writers, however near or far they may be from the Professor-Poet’s obvious admiration of unadulterated self-interest in the artist. Though they may feel their motivation lies elsewhere, the need for money or ‘dough’ is a constant tied to the survival of any artist if they are, the basic requisite of survival, to remain alive. After all, Jack must eat: to show that is one reason we see him eating in the novel, if somewhat functionally and badly, so often. Though Jack rarely, apart from the anomaly of the Banker Award, gets enough money for his family to survive from writing alone, we are frequently reminded that this is his motivation in accepting the teaching commitments, implied by his contract with The House of Art and Aesthetics, or other ad hoc jobs dished out to writers.

I was skint and that was that. People don’t buy yer books and ye cannay fucking force them man imagine it! Waiting outside the bookshop with yer Winchester rifle: … [9]

And when you are ‘skint’ Jack realises it means that whatever could be called ‘a job’ is a probable necessity because ‘jobs paid dough’.[10] Even when Jack feels that he only works to feed his wife and extended family not himself (because he, on his own, could, he thinks, live on ‘Scraps from dustbins. Who needs money’), he suddenly remembers that if he lives on at all it is by virtue of his wife, Hannah’s sole income and other warm supportive strength. It may be true that his need for money can be dismissed in the last sentence of a telling and otherwise highly self-centred and self-regarding paragraph, which shows its character in the superb of choice of ‘one’ (in my italics in the following), as if one needed to convince oneself of one’s objectivity. We take pause at how the last sentence of this paragraph ends and the reality of his true vulnerability is brought back to him in the very short paragraph that follows it:

Who needs money. Except one has a partner, one has offspring; offspring of the offspring; appendages to one’s existence. Without Hannah there would have been none of that, without Hannah …

I would be dead.[11]

In a novel that is itself a metafiction (about fiction that hides its author’s subjectivity in plain sight under a ‘I-voice’ (the phrase occurs throughout) that is NOT that of its author and yet feeds from his experience) the writer contemplates self-portraits painted by graphic figure artists. He wonders:

How about writers? Can they do self-portraits? Do writers look in a mirror and try to write themselves down. … Is the story they write in the “I-voice” first person? Is this “I-voice” a character in the story? Perhaps the “I-voice” is the whole story.

What is fiction?

When we draw a portrait of ourselves is it our whole self we are drawing?[12]

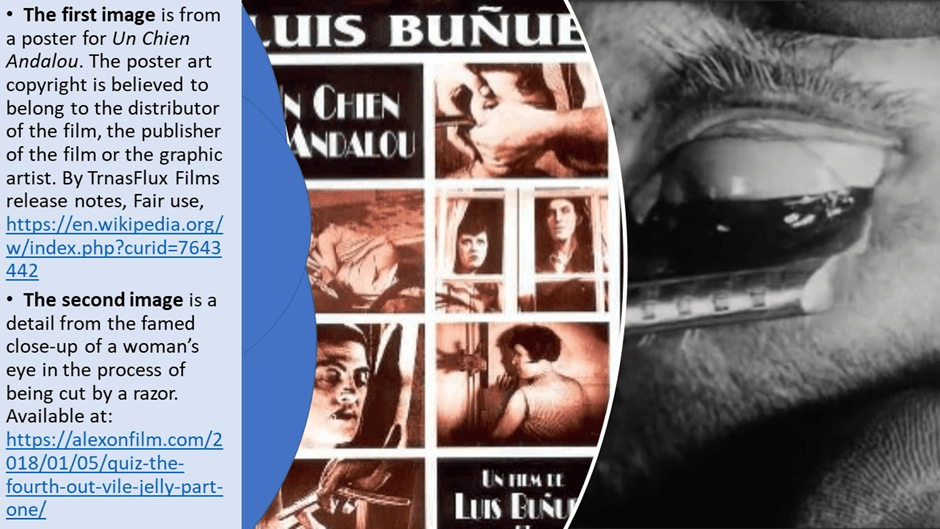

There is something infinitely recessive (and regressive) in such writing in the first person about writing in the first person, which makes so clear that the central problem in a story is the problematic grasp of reality of the ‘I-voice’ itself. But at a simple level, this convolution in considering the ontology of the writer who writes themselves and their substitutive voice or voices, is the answer to cynics like the Professor-Poet, for to the latter self-interest alone is the guarantor of there being a self, an guarantee not available to Jack who might also be Jake or Jock and be speaking in Lallans, an ideological language invented by Robert Burns. A whole chapter (Ch. 42) of the book is devoted to ‘The difficulty of the I-voice ending’, which considers the problem of whether the ‘I’ which names a self exists at all, also considering whether a homophone (‘eye’) of that word also exists for painters. It’s a conundrum Jack / Kelman deepens by referring the whole question to a silent reference to the eye cut by a razor (a razor that also performs the function of Occam’s Razor) in the Surrealist film Un Chien d’Andalou by Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali.

Do eyes exist? What are eyes? Eyes are optical illusions, for is it not the case that the ayes have it, that eyes are “themselves,” in nominee patris one swipes with the razor, ridding the world of nonsensicality.

If eyes be a true reflection of the inner state then outwardly I was awake but inwardly less certain. What time was it?

Kelman’s language plays deconstructive games in which the homophones ‘I’, ‘eye’ and ‘aye’ (a word meaning yes in parliamentary language in the phrase used here to give it context or eternity in Scots). These homophones create secondary ambiguities of meaning around other words that have a similar association in their context here (like ‘themselves’, ‘awake’ and inner / outer binaries). All of those meanings form part of the concerto of concepts which play across the whole work, wherein what it means to be ‘inside’ or ‘outside’ the consciousness of self and / or one other person, a piece of worked language like a ‘toty wee sentence’ or reality and inner fantasy is explored. The opening of the novel alone points us to this (and loses some readers in the process perhaps who do not wish to enter language (get right inside it) in the way Kelman invites us so to do) hanging his words on contrasting outsides to insides on an incident involving the opening of a door.

In mid-sentence when she opened the door, and pausing so as not to interrupt me, finishing a sentence, a sentence being a sentence and is one sentence from inside. It is from inside and I was finishing it. Inside. I was inside. The thing about “inside” as opposed to outside concerns perception and reality, if we are inside then our outpourings, the utterings, cries and squeals that we pour out, within the writing, becoming “outside,” about eh

One toty wee sentence.[13]

I hesitate in the end to say whether I consider this to be a game with language and the internal workings of linguistic features in interacting languages, such as Scots and English, or something more technical about the nature of writing itself, for this is the burden of how Kelman and Proctor define the writer qua artist. I have tried to show that Kelman denies easy social definitions of the ontology of artist / writer. Both are defining by doing art, and no other definition or characterisation of them matters if it is not visible in the quality of their work (their doing of it as a product (itself called a work (of art) of that work). A work may begin as just one word or half a ‘toty wee sentence’, yet it cannot refer back to anything that preceded it or, if to anything, just to an empty page without words, a blank canvas or material for making a record of an aural performance, a presence that is also an absence of art, a mere material on which to work. And one does not become an artist merely by other people recognising one as such and attributing that label, for without work to represent the art there is no artist. Hence the theme that runs through the novel of the Banker award won by its hero, Jack Proctor (although it is obvious to everyone that this theme refers to Kelman too). As we have already seen the name ‘Banker’ opens one issue about what differentiates art from non-art: that art is not the money or the prestige it wins us when it does, which is rarely or never for most writers.

Jack Proctor attempts to teach as he writes, inscribing into his ‘apprentices’ (for thus a journeyman artist sees his students) one very clear lesson: students who merely ‘want to write’ rather than just use every moment to begin to write and thereafter continually revise their writing in order to finish their work, discovering much about the materials necessary to writing those pieces along the way. Those materials of writing may refer to elements of novels like character or story or the ambiguities of single words and the potentials of syntax. Early on in God’s Teeth Jack explains why when he ‘was young’ he ‘loved books about artists’; ‘locked into isolation with no option but to paint, write and study’.[14] The important point is not the life, or being locked in (though that matters too), but that working was one’s only option in that position, for Jack believes that artwork (working to make art), and for him writing, is: ‘a need. It is a fix. I fix to be writing: if not my brains enter a state of expiratory explosiveness.[15] But this is not just obsessive compulsion akin to the fact that Jack ‘needed to be awake…had to be working’:[16] it is a theory of what is essential to the being of the artist: and the essence is a dynamic one. It is work, doing work on art.

The writing is the thing. (…) We’re all fighting for time but other people couldnay care less, and why should they. Then after they fall asleep up we get and do some work on a story in progress. (…) Not shirking the issue. Shirk. I shirk. Expressing shirk …

What we want isn’t a writers workshop at all really it is into the studio itself, the place where the writer works! (…) The artist at work.[17]

There is in this a lot of straining to work out where the artist ‘fits’ in with, if they fit in at all, time and space generally or in any one particular place (such as the lodging house offered to him to live in by The House of Art and Aesthetics). One thing is clear about art, as he tells his would-be apprentices (if to such they really aspire); ‘it’s no good talking about it. Ye have to write it’. The space for that writing is cramped indeed for he refers them the most cramped of spaces and places: ‘the page, the place we work’.[18] Uncomfortable and small spaces with no furniture other than a desk and possible uncomfortable seat are littered through this novel where The House of Art and Aesthetics tries to find a ‘place’ to satisfy Jack’s fulfilment of his residency with them without understanding, or trying to understand, his needs. Jack cannot be satisfied however because he will never allow his mind to rest long enough to pretend, as institutions of creative art do he thinks, that ‘work’ is a soft and comfortable complement to life. Instead the meanings art seeks militate against the those attempting to be comfortable and at ease with a reality that is in fact a cruel one for most people who call themselves workers and mean it. Such people are not satisfied with the cosiness associated with certain adjectives used too glibly of art and ‘Writing’; especially the word ‘Creative’:

I was never Creative. That was my problem. It was all sweat, grime and fucking fuck knows what, sweat sweat sweat, boring boring grind upon grind and draft upon draft upon draft, even that one may sit, aching shoulders, stiffness, draughts from faulty fucking windows one never has time to repair.

In contrast in a passage above the last one he shows us that he thinks that ‘right-wing think-tanks and quasi-government institutions’ stress a notion of the artist that is politically and otherwise passive in a ‘comfy’ chair – perhaps the Chair of a university:

eiderdown seats for visitors and other outsiders such that one cannot stay awake, cannot take cognisance of one’s whereabouts, … remembering one’s arguments against the existence of these think-tanks, publicly funded, purposes of control of us long to reign over us within the community, schools and learning institutions. At least the chair was comfy, …[19]

An artist – requires to awake (the true state of the ‘woke’ so hated by the political right) to the blandishments of fitting comfortably into the space provided by and in the status-quo whilst being effortlessly, it would seem, ‘creative’. For art that is the subject of ‘control of us long to reign over us’ is art that dozes whilst the few profit from the many. It depends of course on with whom the artist identifies: the comfortable or the displaced worker. Jack continually confronts, as I have noted already, scenarios wherein an ‘Arts Control Officer’ who, without consultation, reduces the length and challenge of his talk to learners, expects him merely to fill time with them not teach them: ‘tell them a joke sing them a song, invent a quiz, a literary quiz’ or just ‘fiddle, not so much as Nero as W.C. Fields, old Micawber’. Yet still, whether one is Nero or Micawber in the film, Rome burns: and people in the USA, in this novel at the least, speak of ‘Bony Scallin’ (Bonny Scotland) without thinking that its beauties depend on there being ‘no people hardly at all because they’ve all been shipped to fuck knows where thus not to interrupt one’s appreciation of the land’s unspoilt beauty’. These sentences speak of the cruelties of capitalism run amok in working people’s lives (here the Highland Clearances) under the comfy cover of a love of supposed ‘natural’ beauty.

You cannot easily précis Jack Proctor, or James Kelman, for so much occurs at the level of the writing – the working at the syntax and the lexis of the prose forms. We realise what these guys mean only through how the writing is made and factured, not by looking behind prose for the ideas that inspired it and that, in the long run, might as well be substituted for the prose itself. This is the burden of Jack’s engagement with Ed in one of the classes described, who has prepared himself as a writer by having ‘plenty of ideas. Things based on my own personal experience’ and, having stored them mentally is ‘already shifting things about inside’. This phenomenon is at the crux of the distinction Jack and James make of the factured (or ‘making’ or ‘working’) nature of true art. It is not a translation of things ‘inside’ the writer’s head, for as Jack says, what’s inside the head is really ‘veins and corpuscles; bones, bits of gristle’. He goes on to try and spell out what ‘Creative Fiction Writing’ really means – and it is not Ed’s internal ‘verbal utterings’ in a workshop that should be called ‘Recounting Anecdotes’.

If ye think we’re referring to an activity that exists within our skulls in reference to the making aspect of writing then forget it. Ye have to forget about ideas no matter how brilliant they are, like the poet said, no ideas but in things. Think in terms of physical art forms. What we do is shift things about not inside but outside in the material world; cut, copy and paste. We move sentences and paragraphs from one page to another, … Ye have to be in discovery …/ … This is why you do not understand. It is a learning process. You are within it. You are here to learn. We all are.[20]

This could, and does to Arts Control Officers, sound like so much verbiage but its tendency is exactly the opposite. It is to emphasise that art is that which is active in the making of art as a thing in a world of things not an abstracted idea in a non-abrasive world of mental forms, thoughts and ideas. The latter is too comfortable for both writer and reader. to be art. The poet Jack silently cites in supporting this – supporting it from the work of reading a difficult poets – is no Professor-Poet but the poet-physician William Carlos Williams.

People forget that the demand that learning should be easy belies the obscurity of truth inside things themselves (including poems and pictures that are also factured things) and cannot be substituted for by a world of ideas without agency that can be learned and/or forgotten with no significant difference occurring dependent upon which of these things occur. Jack engages with his learners as if they were apprentices ready to make things as he does and needing to be reminded of the work this involves, work in uncovering the baseness and self-interest involved in the wish for ‘secure space’ rather than realise (comprehend the reality of) the discomfort of the real as it exists for those without privilege ‘within a harsh uncaring world of universal exploitation’. For security in our world is only security for the entitled. This is surely the point of the story Jack tells one group of learners on a college campus about being challenged by a security officer in the name of ‘Collegiate Security’. Outsiders are challenged as people who don’t belong, who disrupt what is cosy and exclusive, but writers need to make the choices, Jack implies to the learners, to live outside such guarded spaces and within spaces in the external world where they can at least gain ‘the requisite work-level experience in different social settings’.[21]

I love Kelman. He is the greatest of our artist-writers still. This novel is yet another triumph. Nearer than any other to be being his Biographia Literaria, it still evades the comfort of personal reminiscence and does not luxuriate in the different roles a poet might take on, as does Coleridge. Jack like Kelman is accused of sexism and hypocrisy, of being unwilling to bend to the needs of others when he believes truths must be told and appearances critiqued for what they hide but he is not Kelman, just another ‘I-voice’ who shows us some things and remains unable to even sense the others. As a result, it is a story that revels in the dark side of seers as well as on the light they shed. Jack’s selfish suicidal thoughts and refusal of tact or sensitivity sometimes shocks, for he must forego this in order to show how he fulfils his need to understand his situation inside his writing, at whatever cost of discomfort to self or others. One of my favourite passages illustrates this – for it shows the complexity of the need to understand – to grasp being one of the earliest forms of sensory-motor physical actions in the acquisition of thought for the child according to Piaget. At the very beginning Jack observes a contrast between his wife, Hannah’s, hand and his own. That Hannah uses softness in her grasp of things is clear as are the warmth and security this evokes, but Jack’s grasp is akin to the possessiveness of the capitalist or even the miser, for how else could he understand the enemy. It is a rich piece about hands (the things that do work), a piece where there may be ‘no ideas but things’ that just are what they are: ‘… a nice hand, a strong hand; slender but strong; unlike mine, thick and grasping, a grasping hand for a grasping bastard for that was me, a grasper’.[22]

Do read this novel. It is wonderful.

Love

Steve

Other of my Kelman blogs (brief):

DIRT ROAD

KURDISTAN

[1] James Kelman (2022: 340f.) novel, God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena Oakland, CA, PM Press

[2] Ibid: 21

[3] ibid: 8

[4] Ibid: 75

[5] Ibid: 32

[6] Ibid: 169

[7] Ibid: 139. TLS = Times Literary Supplement, NYR = New York Review, LRB = London Review of Books, McS is unknown to me and may be a spoof or the differently articulated and non-Scottish name (because not McS) MCS, The Literary and Debating Club for Students at MCS Literary & Debating Club | Facebook

[8] Ibid: 171

[9] Ibid: 3

[10] Ibid: 4f.

[11] Ibid: 4

[12] Ibid: 80f.

[13] Ibid:1

[14] Ibid:19

[15] Ibid:13

[16] Ibid:21

[17] Ibid:63

[18] Ibid: 140f.

[19] Both pieces from Ibid: 17. The second cited precedes the first on the page.

[20] Ibid: 134ff.

[21] Ibid: 201-3

[22] Ibid:2

3 thoughts on “The narrator, of James Kelman’s 2022 novel, ‘God’s Teeth and Other Phenomena’, Jack Proctor, a writer who identifies as working class, says of his experience as a resident writer in ‘The House of Art and Aesthetics’ in the USA: ‘I had a glorified view not just of art departments but colleges and universities, as intellectual hotbeds. When I discovered the truth the disappointment of that stayed with me and it’s with me right now’.[1] A great author summarises his disappointment with the notion of elite culture and the pretence of knowing what art is without working hard to do it.”