Joseph Ortiz makes a brilliant case in his new biography of Gordon Merrick for describing the artist’s achievement as the invention of the Great American Queer Novel. This blog ponders on whether Merrick was a better model for our own era of the potential of an open sexual diversity in Merrick’s own, despite the claims of Violet Quill writers to be the voice of gay men as they actually were. I think that what we conclude may hang on our beliefs about what a queer novel is and how it differs from a ‘gay’ novel. In my view the queer novel advocates for complex forms of diversity and ideas of the intersectional and transitional in the understanding of identity rather than being an affirmation of one unique (and therefore possibly stereotyped) group identity. The blog is based on reading the Charlie & Peter Trilogy and Joseph M. Ortiz (2022) biography Gordon Merrick and the Great American Gay Novel, Lexington Press.

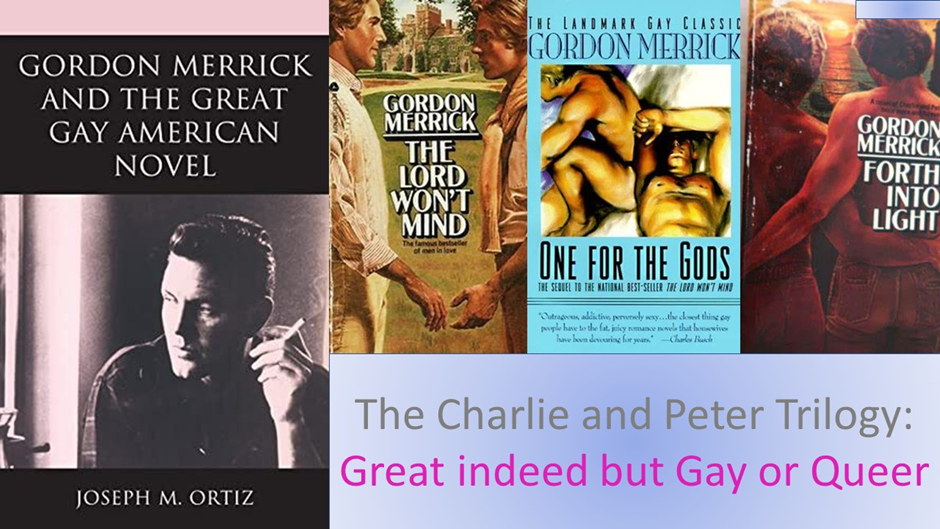

The cover of the Ortiz book and versions of the paperback editions and the story told by their covers.

I discovered Ortiz’s new biography of Gordon Merrick in a review of it in the current (November-December 2022) issue of The Gay and Lesbian Review (G&LR). What I had not taken seriously however when this review prompted me to start reading the novels were the possible sources of bias in that review and which only came to the fore to me on reading Ortiz for myself. I read Ortiz after reading, for the first time note, the most famous of Merrick’s novels, which he latterly collected as the Charlie and Peter trilogy. According to the G&LR review, these books were the main topic of this ‘biography’ which it claimed is really rather a literary critique of those key novels. Thus it took me by surprise when I found that the books make their first appearance ‘halfway through the book’ only, as Tom Cardamone says in a rather more factually structured review for Out in Print: Queer Book Reviews. Cardamone goes on to say that from this point those readers ‘can look back with wonder at a journey well-told’, presumably because they will be able that what was in the book up to this point is the same privileged life-story on which the novels are based [1]. The G&LR’s claim that the whole biography hangs around those three key novels however misses the point raised only by Cardamone that the first half of the biography makes available to readers the interesting early novels about which it usually thought okay to be ignorant and superior, because they deal in large with heterosexual heroes and only bit-part stories of gay men. Reading, after Ortiz, The Strumpet Wind – Merrick’s first novel – opened my eyes to the fact that the latter summary is a travesty of those interesting novels, which E.M. Forster admired and which I shall blog about after this blog (in time and time permitting!). The G&LR reviewer has other limitations (as a reviewer); starting with apparent, if condescending, empathy for the novelist at first but ending with something that is, to my ear, archly condemnatory:

In his astute chapter on the “gay canon” … Ortiz points out that Merrick was criticized for not dealing with Stonewall and AIDS. Merrick, …, wrote as if Stonewall and AIDS had never happened. But they hadn’t to Merrick, because he was living abroad. …

….

Merrick chose to live outside the country that he “hated” (he told a French interviewer), no doubt because he didn’t see why he should wait for his fellow Americans to catch up with his own view of things. There was a curious amalgam of the confidence of an entitled American – his lover Charles Hulse’s younger brother, after visiting the pair in Hydra, thought Merrick a “pompous prick” – and the fear that his homosexuality would make him vulnerable to a society “where he would be doomed to hostility or derision or the half-world of exclusive homosexuality,” in the words of one of his characters. In other words, he was not attracted to the gay ghetto; he simply wanted to love men.[2]

Of course, the condemnation is modified. A ghetto is no-one’s idea of Eden, after all, although one can share the reviewer’s sadness when we see Merrick’s view of the ‘gay scene’ (in Ortiz’s terminology which comes from the ‘scene’ itself) as ‘an insular ghetto – a “half-world of exclusive homosexuality”’.[3] Even later in life Merrick could say in a 1979 interview that “this whole gay-lib thing – the last thing in the world I’d be against” was also a concern because it had “a tendency that it inevitably has of solidifying a sort ghetto feeling”.[4] I think we need to come back to this in a more empathetic manner than the reviewer does later whilst recognising that the musical underscore in this review is that Merrick is a novelist limited by his class, social status and inherited wealth and confidence from full commitment to gay people: a rich white man ‘entitled’ in ways that cut him off from the more ordinary world of ordinary gay men. And the reviewer has a point because Merrick was ‘entitled’ by virtue of his elite Princeton education and the social reality of birth to a monied class. He, in all probability, could also be rightly thought a “pompous prick” with his urbane and literary airs and graces.

These airs and graces emerge not least in Merrick’s implicit insistence that, as strongly as T.S. Eliot did, that he was writing in a literary and sociocultural tradition that belonged not just to modernity but to a long ever-varying tradition that often paid homage to Greek and Latin classical models as well as André Gide and E.M. Forster. Thus, as Ortiz shows, the heterosexual and literary cultured hero, Stuart, of the 1954 novel The Demon of Noon, can still be touched by queer lives through a sub-plot related to his son, Robbie. Caught having sex, with Toni, a heterosexual who nevertheless is sexually attracted to Robbie, Toni’s ‘silly little pédé’, Robbie turns his father’s culture back on to him: ‘”I didn’t ask to be that way. There’re books about it. What about Gide?’[5] Moreover The Demon of Noon used an epigram from the nearest of Forster’s novels to a gay male romance The Longest Journey, which also provided the title for a later major revision of that novel to fill out its explicitness as a fully-fledged queer novel (Perfect Freedom): ‘Perhaps each of us would go to ruin if for one short hour we acted as we thought fit, and attempted the service of perfect freedom’.[6]

And in the middle of omitted parts from the long quotation above, the L&GR reviewer sees Merrick’s connection to European and stuffy English models rising up to further typify a flight from a group gay identity that is distinct from the culture of hegemonic heterosexuality:

… Merrick, true to [E.M. Forster’s] Maurice, gives his men a happy ending. It ends with the children they’ve fathered coming down the stairs in all their glory. In other words, it ends with something very like the current state of gay liberation: marriage and children.

The last statement silently ridicules the ‘current state of gay liberation’ as something to which the writer clearly feels antagonistic. Of course, it is all very subtle, but it adds up to seeing the ‘case’ of Gordon Merrick as an example of a betrayal of ‘true’ gay male culture by the upper bourgeois culture of the American White Anglo-Saxon Protestant tradition exiled in the luxuries of Europe. For this reviewer hints that the true basic interests of gay people (though he means men really) in these parlous days, whilst entitled gay white men get personal credit and validation from a basically heteronormative society. And when even Europe fails Merrick, because Hydra has become too full of tourists, ‘a place close to a beach on the Indian ocean’ in a former British dependency, Sri Lanka.[7]

Only those rare readers who look at footnote references will have noticed that the G&LR reviewer, whom I have not before now named in this text, is the Violet Quill novelist Andrew Holleran. And this is not an insignificant fact for Ortiz references Holleran throughout this biography. Near the end of the biography he names him, together with Edmund White, as literary stylists and linguistic innovators in another ‘league’ than Merrick (in a chapter on the ‘gay canon’ that Holleran praises in his review).[8] Near the beginning he also says Holleran reminded him that, despite Ortiz’s romantic attachment to the apparent world painted by Gordon Merrick, this was a longing for something born of a limited perspective on that world; for Ortiz says: ‘It was Andrew Holleran who taught me that I was nostalgic for a period I had not lived through’.[9] And the attitudes I caught in the tonal ironies of Holleran’s review of the book very much belong to the period of literature in which ‘gay liberation’ (represented by Stonewall and AIDS activism) began to see the world and ideals represented by Merrick as extremely limiting.

Holleran was one such participant in identity liberation culture. In 1978 Holleran was castigated, Ortiz reports, for making ‘a condescending remark about Gordon’s novels’ by British Gay News journalist Keith Howes who also pointed out that Holleran himself had avoided the kind of damaging publicity associated with writing about gay male sex in The Dancer from The Dance (see my blog on this at this link), which Merrick had more directly embraced, by avoiding ‘media appearances’, giving no autobiographical material at all on his book’s dustjacket and, indeed, publishing under a nom de plume (Holleran’s real name is Eric Gerber).[10] Holleran’s objections in his review to the ‘current state of gay liberation’ as over-obsessed by gay marriage (as an emblem, as he sees it, of gay men ‘giving in’ to heteronormativity) was represented at the time in print by both male gay activists and the Violet Quill movement, which included Holleran (again see my blog on this and a work by Felice Picano at this link). Felice Picano was the most radical of these voices (among the Violet Quill group at least) – have a look at another blog for why I think this is the case – and certainly Ortiz believes that Picano is willing to ‘fudge’ the dates of Merrick’s creative periods; moving ‘Merrick forward in time by nearly a decade in order to situate him “outside the canon” of serious gay literature’ and placing him in a despised genre – the heteronormative values (as they see it) endemic to ‘gay romances’.

Otis Bigelow photograph available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Otis_Bigelow.jpg

Merrick then was in his own time painted by his chief critics as intrinsically antagonistic to gay identity. This view has some support from Merrick’s early friends Ortiz tells us. For instance, his relationship with the actor Otis Bigelow as a young actor like himself was racked by Bigelow’s willingnees to take comfort in ‘gay hangouts and parties’. Bigelow later said of Merrick in fact that the latter was “very into not being gay”.[11] But we have to remember that he was a very young man then and that, as Ortiz says, his instinctive recoil from ‘the flamboyant and effeminate gay men who lived in the city’ he knew as the “gays” or “fairies” was superseded by finding as he aged that ‘it was increasingly difficult to distinguish himself from the “gays” and “fairies” he was constantly meeting’.[12] And although some antagonistic critics cite the views of the young Charlie (seen as a simple avatar of the author) in The Lord Won’t Mind, they often forget the irony in this portrait, the purpose of which is to show deficits in Charlie as a undeveloped young queer man that we don’t find in the much more attractive (if slightly less well endowed with phallic power) Peter when both are still young men.

Submerged in the undifferentiating energy of their sexual dynamism they seem indifferent to the labels given to them. The young Charlie, for instance, ‘had never considered himself a fairy or a pansy or any of the other words bandied about contemptuously’ because his ‘sexual activities with other boys were a natural extension of the play he had been introduced to at school’.[13] The contemptuous seems bound into those effeminizing words and into the word ‘queer’ so that Charlie can even use it against Peter while happily introducing him to the whole range of gay sexual activities. For instance, discovering that Peter had been at his golf club ‘out on the lawn with a queer’, he proposes that should they ‘had so much as touched each other, he would kill’ Peter ‘for making him feel like this’.[14] In slightly more open mood and as he grows up as a lover of men primarily he accepts that Peter and he might love each other but only if Peter ‘wouldn’t turn it all queer’ with his talk of stuff Charlie calls ‘homosexual crap’. When Charlie grows habituated to life in a bed-sit with Peter and, working as a jobbing actor, he becomes aware that he might best get a job by accepting proposals of sex with queer directors[15], he becomes aware of his need for Peter sexually and romantically. After all by then he has tried heterosexual marriage for a spell. Now he says to Peter that he is, “All right about the queer part” in his love for him for:

He had penetrated at last to the core of himself. Awareness had been slowly filling him. … layers of the fabrication on which he had built his personality had been stripped away until he reached this ultimate exposure. … He was this little thing crying for acceptance.[16]

Randy Wicker – the non-exclusive partner of Peter Ogren

The Gay Liberationist movement in the 1970s saw, as Holleran silently recalls in his review of Ortiz, the kind of fear of independent self-defined gay life, which they thought of as the whole of Merrick’s message, in the call for ‘Gay Marriage’, a phenomenon which the gorgeously named Randy Wicker saw as ‘a Heterosexual Trap’ for the autonomy of gay identity. Indeed, this was the title of an essay by Wicker, who lived with one of the earliest gay movement reviewers of The Lord Won’t Mind. Peter Ogren. For them both, Ortiz says, in summary of their joint views:

The real problem with Lord was that it was too assimilationist. Charlie and Peter’s relationship is too much like a conventional marriage.[17]

This view must have seemed very much proven when in 1981, with a ‘gay marriage boom’ in progress, according to the San Francisco Chronicle, the Avon publishing team of the paperback of One For The Gods explicitly advertised the novel in terms of positive representations of ‘homosexual marriage’.[18] This view was not just a publisher’s ploy for ‘marriage’ does form part of Charlie’s journey to self-acceptance through a route involving being accepted first by Peter as a lifelong partner. In One for the Gods, this is spelled out. Charlie thinks of their bonded state in bourgeois marriage-like terms: ‘They weren’t queers like these others. They were two people who were in love with each other and had made a decent life for themselves’.[19] A little earlier in the novel, Peter, whilst trying out an affair with a younger man still thinks of the rightness of sex with Charlie: ‘That was who he belonged to, always had and always would: he would love to have it publicly recognized as a marriage, which is what it was’.[20]

These are signs eagerly jumped on to support the supposed refusal of a distinct ‘gay identity’, that required no validation from the symbols of heteronormativity, in Merrick’s work. This suspicion was reinforced further by the apparent refusal of Merrick to acknowledge the significance of AIDS in creating an opportunity for the expression of gay male communality (though AIDS was of course not just a gay male phenomenon except in terms of a statistical trend). In 1986 Holleran claimed AIDS responses and activism were definitive of the mindset of the historical situation of the USA’s gay male community, going as far as saying of one city that: “The whole city has shrunk to a single fact”.[21] To say that Merrick ignored AIDS as a writer is true but I do not take from this the idea that this was because he still was defending a position for gay males that accepted its powerlessness. Rather it had much to do with the fact that queerness could not be summarised by a unitary identity for him, which was what he meant, I think, by ‘exclusive homosexuality’, to wit an identity that excluded others even those of its own community for whom identity was more complex than being only a ‘gay male’.

There is a truth here in his position for our own time, but it is not what Holleran thinks – that models of heterosexual marriage were adopted to quiet the struggle for gay identity and tame it to a heteronormative world. I would defend his position by arguing that multiple kinds of queer identities regularly fail to meet the criteria for a singular identity type such as that supposed in the ‘gay man’ and that, in this sense, Merrick unearthed an important lesson for our own times that, in some ways, the search for such identity was misguided and does solidify into a ‘ghetto feeling’. That feeling is a kind of ideological homonormativity, not because it aped heteronormativity as in some definitions of the term, but that it allowed no alternatives in sexual and amative in the ontology of queer people. Thus, from the experience of his own time, I believe (with Ortiz I think) that Merrick found some truths of our own time. This is not a position I believe Andrew Holleran would even now willingly embrace, to understand which we need to think about Gay Liberation ideology before we return to queer multiple (and intersectional) identity as opened up by Merrick’s lush Charlie and Peter novels. Partly this is represented by Judy, in the final novel, whom, despite rather liking penetrative sex with Peter, returns by choice to be a lesbian raising his child, ‘biologically speaking, with a female partner as its true parent.

Merrick and the class he represented are in part the subject of Holleran’s The Dancer from the Dance. As I wrote in my blog on that fascinating novel, apart from the fact that they stayed in America the world of elite ‘queens’ in Fire Island is the world of Merrick, in that it realised, in a kind of exclusive gay male American holiday resort (or internal exile from straight values) for the rich the meaning of Merrick’s more real exile. This is I think is the decadent but somewhat beautiful world with which Holleran associates Merrick. And though Holleran finds aesthetic beauty in this world, he finds little in the way of political truth. As I point out in my blog, Holleran’s characters in that novel’s Fire Island world have an intense fascination with ideal male beauty supported somewhat tenuously by a pastiche of the values of Greek art. Such ideals probably historically derived from the manner in which Johann Joachim Winckelmann (see above) united his contemporary eighteenth-century Baroque fascination with the haunting beauty of the ultra-masculine military male body at rest or play with the beginnings of the art history he generated.

Among the contradictions, that I also point out in the Holleran blog, is that displayed in his Fire Island queens, which valorise a model of the man who had sex with men, it would seem, only the athletic bodies of ideal men, often Latinos, even though they may seem like an Ancient Greek statue in their beauty, represented a desired masculinity, as it never is in Greek statuary (see the above collage). That is because, except for the common or garden animal lust of the satyr with its prodigious phallus, boyish well-proportioned phalli are de rigueur, as in the example in the Winkelmann book illustration above. This contradiction we can trace perhaps in part to Gordon Merrick as a source for Holleran too if we also have to evoke the observed behaviour or chat about their behaviour of real gay male communities, at least those privileged members on Fire Island. However, I allow myself to think that Merrick may be pointing to this contradiction between ideal Ancient Greek or ‘Renaissance’ bodies in showing that the only man with a modestly sized ‘sex’ in his novel is the young Athenian, Dmitri. Dmitri follows Charlie to Hydra in the second volume and eventually (in the final volume) becomes a bar manager and the first male lover of the lovelorn and tragic young English boy, Jeff Leighton, about which more later. Dmitri is even conceived as being like ‘a drawing’: ‘As in a drawing, his sex was discreet but satisfyingly in scale, shadowed with only a light blur of pubic hair’.

David Leavitt’s famous objections to Holleran – that he inculcated a belief in the necessity of good looks, athletic body and a large penis as the price of ‘being gay’ is, as I tried to show in my blog, not Holleran’s aim but the aim of his characters, who are self-consciously a group passing out of history in the interests of Gay Liberation. In that blog I say:

… that the point of Holleran’s art … is one quite distinct from that of his narrator and the friend to whom they write. The latter writes in the letters prefacing the novel: ‘Your novel might serve a historical purpose – if only because the young queens nowadays are utterly indistinguishable from straight boys. The twenty-year olds are completely calm about being gay, they do not consider themselves doomed’. I think, but call me old-fashioned, that Holleran calls out here on behalf of those new young people who are reasserting queer identity. Only a line before that last quotation Holleran identifies these as gay liberation ‘activists’, ‘who want the world to believe not only that Gay is Good, but Gay is Better’. [22]

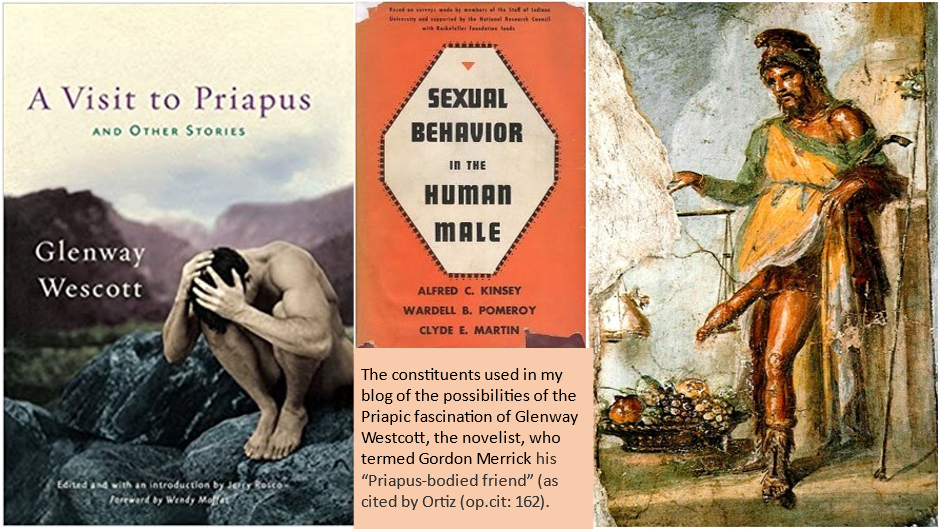

In terms of the fascination with a large phallus amongst the gay communities pictured, Merrick may indeed have been boasting in his presentation of the psychic fascination (narcissistic and from others) that Charlies ‘sex’ causes in both men and women in The Lord Won’t Mind and the other Charlie and Peter novels (it is hard not to find this somewhat laughable after many repetitions of it). We might think that because his hero as an American novelist, Glenway Wescott, made Merrick one of the many men against whom he mourned his own supposed penile deficiency (supposed because his right to call himself small was contested personally by his friend, the sex-researcher, Alfred Kinsey (see my blog on this at this link). Westcott introduced Merrick to E.M. Forster, ensuring both became early readers of Forster’s unpublished gay romance Maurice, and called Gordon (although maybe not to Forster because Ortiz is not explicit about the quotation’s source) his “Priapus-bodied friend”.[23]

To Holleran’s obvious amusement in the review of Ortiz’s biography, he notes that in Merrick’s novels, although the words ‘cock’, ‘dick’ and ‘prick’ are also used, the penis is usually called a man’s ‘sex’. To Holleran this is the perfect example of the ‘blending of Edwardian manners and modern sexual frankness’) in this writer generally.[24] That existence and grandeur of the ‘sex’ of his heroes, but particularly Charlie, is noted throughout the whole trilogy to the point that it becomes an icon of masculinity, power, and potency (as well as fertility) itself. Even Merrick’s contemporaries amongst fashionable queer writers were wont to lose their temper with the constant loving reference by himself and other’s to Charlie’s large sex, and to that of Peter which runs just shy of Charlie’s grand size.[25] Edward Albee (“You have an eight-inch cock and I have a an eight-inch cock but we don’t write about it, do we?”) and Noel Coward (“We don’t talk about it.”) are examples cited by Holleran from Ortiz.[26] In the second and the third volumes of the trilogy the Priapic becomes indeed an emblem of male power, rather than the delightful toy it is for Charlie and Peter in the first volume.

The penis becomes a complex symbol from the moment in the book it is subjected to multiple perspectives upon it in relation to both its visual impact and sensual effect during sex with increasing numbers of eyes and orifices respectively. At first enjoyed only by Peter in the reader’s knowledge (until volume 2 flashbacks), it get increasing airings before women, other men, and young guys. Indeed this is true for Peter too, who, while still acknowledging Charlie’s edge in this regard, likes to see the power of his penis reflected by others, such as latterl in the third volume Judy, once a lesbian, and the hapless late adolescent Jeff Leighton. Young Jeff sees a large ‘sex’ as the absolute standard of the meaning of sexual fulfilment and in the thought of that, in Forth into the Light, he kills himself whilst ejaculating, as almost an icon of the gay identity with which he desires to be fulfilled. The language about the penis in that final volume becomes increasingly exaggerated. It is a ‘prodigious sex’ and eventually is described as ‘monumental’ recalling the huge statuary forms of Delos, which Peter and Charley see in One for the Gods.

The shrine of Dionysos at Delos. Attributed to Apollo in the novel

Jeff prays for Charlie to ‘f-k me so hard it hurts’ and says to Charlie, as he is being penetrated: ‘Yes like that. You are Apollo. Nobody else could be so colossal’.[27] It’s easy to see in that example why I believe that it is worth getting this embarrassment regarding the Charlie and Peter novels over quickly lest it disguise what is excellent in them beyond a stuckness, in Holleran’s fixed view, of the earlier novelist in this culture of the beautiful man with a huge ‘sex’ that simply captures everyone’s attention.

In my view, as I read more and more Merrick, for he passed me by as a young gay man in the 1980s when I might well have been reading him, his modernity however is precisely in his refusal of the simplistic identity politics which make Holleran’s message regarding the new era of Gay Liberation (I was part of that) as I take it to be in The Dancer from The Dance so much less interesting than his doomed set of Fire Island characters and the mix of vulgarity and the aesthetic in the life they represent. What those characters in Holleran lack, if they represent a world in some ways like the elite one of Gordon Merrick and his European exile socialites, is a genuine politics embedded in the person considered as someone who has to survive in a world not yet transformed to an ideal, whether that be Gay Liberation ideals or a wider set of values respectful of human diversity across all boundaries, including those that make us individuated from each other. Merrick began writing with an ingrained commitment to social justice, particularly in defence of the powerless, despite (or perhaps because) of his privileged background.

Ortiz describes him as using ‘his talent to rebel against the structures of American capitalism and class privilege that had shaped his upbringing’[28]. This kind of radical democratic focus was valued more in European circles and Merrick was praised by Georges Roditi in 1950, as representing a character leading ‘une révolte individuelle contre la société américaine’.[29] American reviewers feeling the McCarthy wind were less generous about such politics: and he responded to reviews of his first novel The Strumpet Wind, accusing them of being blind to his exposure of the “basic contradiction” in American values: “We talk of human rights and yet we tolerate religious and racial prejudice of almost medieval fury. We talk of the dignity of the individual and yet our standards are almost entirely material”.[30] Of course, it is axiomatic that young privileged white men make mistakes about understanding exclusions of race and class and most may find his empathy for the working-class Hydra ferryman Costa in the final volume gratingly condescending as an example of class solidarity with the socially excluded.

Moreover, the picture of racial difference can be equally condescending in The Lord Won’t Mind and elsewhere, though there is an attempt to capture the radical in the Harlem Renaissance, although it is anachronistic (because the setting is twenty years later) to see it in the period in which this version of it is set here, and to expose entitled white hypocrisy, as in Charlie’s suave, delightful but brutally right-wing grandmother. Ortiz himself says that ‘too often’ what we find throughout his career is ‘a clumsy attempt by a white man to imagine a black (person’s) experience’.[31] Nevertheless Ortiz feels, as did I even before reading Ortiz himself, that there is a bow to an understanding of identity that is intersectional rather than about unique identities or even double oppressions. In one way this makes him keen not only to explore female subjectivities around sexuality but also more “fluid” identity that are categorizable easily even as bisexual, as is more obviously done in relation to Rod in The Quirk.[32] Both Charlie and Peter have sex with women, though belatedly on Peter’s part and both share a relationship with the mother of both of their children who lives with them. Although Holleran uses the presence of children as a sign of succumbing to heteronormative values, the important difference is that Merrick presents relationships where both partners may have multiple partners of either sex/gender.

The effect is to examine the fluidity of the social constituents of sexual relationships and the invention of novel multiple identities that this generates as well as fluid boundaries between these roles. But these roles also have fluidity across other boundaries of culture in which class, age, race, and sex/gender create new forms of queer identity in which all the constituents of identity must be fluid – not just in being the member of an alternative to normative families but also the different ways in which the working and different ethnicities experience sexuality. There is a beautiful exploration of how age influences identity in interaction with other factors. It explores the arenas in which people sometimes have to rethink and ‘remake themselves to avoid the future as an ‘old queen’ or other stereotype of the aged, often with its own sectional bias. In relation to class Ortiz says that Merrick grew to a mature understanding of the ‘complexity – what we would now call the “intersectionality” – of sexuality and class’.[33] He refines this idea later using the explanations of Bill McCauley about why Merrick is often excluded from the ‘canon’ of gay literature saying:

Merrick’s novels appear confused about gay identity because their characters are confused about gay identity. They struggle to find a language, a “code of communication,” through which they can understand their romantic and erotic feelings towards other men while still coping with the reality of their other socially defined roles (gender, age, class, family). For McCauley, the fact that Merrick represents this complex negotiation of identity shows that he was “well ahead of his time”.[34]

My own feeling is that there is some attempt, especially in The Lord Won’t Mind which really does address this issue around race, despite the stereotypes through which it might be felt that is done. The awful C.B., Charlie’s grandmother mouths a condescending appreciation of Black people for instance seeing them, in the case of her maid Sapphire, as ‘children or very nice animals’, saying that it’s a ‘scientific fact that their craniums are smaller than ours’.[35] Yet this version of ‘scientific racism’ (still prevalent via the psychologist Hans Eysenck when I was in the 6th form at school) bows to embracing Sapphire once she is a socially established stage singer. Sapphire is met again by Charlie in a party, where she tells the story of his gran. The party is created as an emblem of the Harlem Renaissance with its boundaries between black and white, straight and gay thoroughly confounded: a gathering described as ‘mixed, black and white, men and women, men in the majority’. Peter is one of the white men here now crossing class boundaries by making money from relationships with numerous men without quite being a prostitute and engaging with Hughie Hayes, a Black male, in camp fun ‘on a bench at the piano’. In this party Charlie confronts his own belief that he has:‘no racial feelings’ , with evidence indeed of the unexpressed opposite as his skin crawls seeing ‘whites and blacks sitting around together’.[36] At this party Charlie learns of Peter’s working name and reputation as ‘The Growler’, his sexual trademark.

Later C. B’s specific racist sensitivity is explained in terms of her belief that she herself, and hence the whole famil including Charlie, is of mixed race – an identity she fights as if it were a ‘beast that is in me’. It is a moment where racist pastiche falls into a rut Merrick should have avoided but it is indicative of the fact that, in these novels, identity is never fixed nor stable, even to its own history and this reflects too on reflections on being queer or ‘bisexual’ (a peculiar experimental fancy of Peter’s in One for the Gods). In relation to class and social status identity also gets confused around work roles – those of actor and accountant for Peter and the expectations of the employed and employed in relation to each other, the distortions caused by celebrity or lost celebrity, as in the story of George Leighton and Joe Cochran in the final volume. In the end Merrick is wise to the notion that power and one’s relation to it often supplants any bid for an ‘individual identity’, let alone the choice of an exclusive one. In The Hot Season he expresses it thus as cited by Ortiz: “The source of power is far removed from the live of the ordinary individual. … political action as you conceive it, as an expression of individual will, no longer has any meaning”.[37]

Moreover, as Holleran says, by and large Merrick was also reacting successfully in the Charlie and Peter trilogy against a literature in which queer people were represented as ‘doomed’ to isolation, social exclusion and suicide (though some of his early novels are precisely from that tradition as Ortiz also says too of The Demon of Noon). I would argue that there is a maturity in Merrick that refused to ditch that paradigm from earlier gay fiction in the Trilogy, resurrecting it, as Ortiz illustrates, in the story of the young man Jeff and his suicide in Forth into the Light , the final volume of the trilogy. For negative fictions about gay people do not disappear by the force of the wishful thinking of liberationists or even through campaigning. Jeff kills himself because he fails to see the difference between ideals and reality and because his future in America is as likely to see him abused by older gay men as he is by both crooked male controllers of no distinct sexual identity except that of displays of power and control like the successful potboiler novelist Mike Cochran Or ‘innocent’ exploiters in the way Charlie becomes as he weighs up how to keep Jeff as a kind of sex toy as if as a gift to Jeff (for it is a truth of these novels that, even by the end, Charlie does not really know himself as he can be – indeed few of us do). And young gay men still formed a high proportion (and growing in a 2016 Canadian study – a country that takes these things seriously) of male suicides even in post-gay-liberation days, not least because sexuality has no size that fits all and alienations still occur.

Merrick chose to be honest about young gay male suicide, even if by using a literary trope of which Ortiz convinces me that Jeff’s story in Forth into The Light is, and which ends that novel by emphasising in its melodramatic pastiche the manner in which social codes engineered Jeff’s death. Jeff’s life and death, resolve for Jeff himself into Greek myth wherein Jeff plays the role of Apollo’s lover Hyacinth, killed inadvertently by Apollo’s discus, as in the tremendous painting by Tiepolo, overpowered by love of the monumental power of Charlie’s phallus: ‘He had been loved by Apollo. He had aroused the jealousy of the Gods. The discus had been arrested and reversed in its course. He could sense it hurtling towards him’.[38] It is reported as blame for behaviour beyond the lawful norm, worthy of iconic death: ‘He entered island legend, an example to sinners, as a lovelorn boy who had been driven to destroy himself by the enormity of his unnatural crimes’.[39]

However, otherwise Merrick is often accused of providing happy endings for people whose overt beauty is concentrated upon. And though here he will often invoke Greek models for his men such as Apollo, as an avatar for Peter and Charlie, Narcissus (inevitably) and Ganymede. The dependence on Greek myth is the validating standard of the world of Merrick’s heroes. We meet these literary archetypes frequently and more so as the novel progresses. For me this has something to do with the way in which the book makes the manner of art and artistic tradition its theme. Charlie is a painter. George Leighton and Joe Cochran are writers of different kinds. Art is used as a means of decoration in this novel, as a financial asset but also as a means of exploring how beauty and integrity might meet in a world of fragments. At one point the passage of time is written by Merrick as a confused almost abstract landscape in Charlie’s mind in which thoughts of war impinge and the ‘past is people moving against a vague background of events’.[40] For reality can’t be turned into images of simple beauty or moral or compositional integrity. What Merrick seems to revel in within the trilogy is what Charlie calls in the early part of the novel the ‘aesthetic exploration’ of a lover’s body.[41]

Such exploration is done by drawing and writing – bringing to light scenes usually hidden, as Charlie hides pictures of Peter naked in a drawer. Such an attitude fails Jeff Leighton as perhaps it fails everyone who will not see the accidental (event-laden) contingencies implicit in passages of time. Yet Charlie aims to mend things but creating in his painterly eye a ‘solid composition’. Herein are the various Renaissance and classical figures the novel sets against the mess of events in time such as wars and poverty. Thus, visiting the discovered male young lover of Peter in One for the Gods, Jean-Claude, Charlie imagines him as art to cool the pressure of contingent jealousy at events. Looking at the young French boy he sees him as ‘a fine figure of a youth, a painted statue; all the lines flowed softly into each other like Hellenistic work, faintly hermaphrodite’.[42] However, This is merely one of the strategies used to refine how Merrick translates the mess of sex-relationships, with all intersectional factors in play.

Another is the invocation of an idea of coded communication and the hidden (consciously or unconsciously). I want to write about that but will leave it till another blog which starts with an analysis of The Strumpet Wind, a play with the world of espionage of which Merrick was a part in the Second World War, broken trust, treachery, loyalty and secrecy. For this is the queer world, forever in love and resistance with the world as it is as it pretends, like everyone and thing in it, to be something else. See you at the next blog. (hopefully).

Love

Steve

[1] Tom Cardamone (2022) ‘review’ in Out in Print: Queer Book Reviews (October 3, 2022 · 11:04 am). Available at: https://outinprintblog.wordpress.com/2022/10/03/gordon-merrick-and-the-great-gay-american-novel-joseph-m-ortiz-lexington-books/

[2] Andrew Holleran (2022: 15) ‘The Curious Case of Gordon Merrick’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review XXIX (6) (November-December 2022), 13 – 15.

[3] Joseph M. Ortiz (2022: 216) Gordon Merrick and the Great American Gay Novel, Lexington Press.

[4] Ibid: 385

[5] Cited ibid: 182. See pp181 – 183 for novel summary.

[6] Cited ibid: 166

[7] Holleran op.cit:15

[10] Ibid: 394

[11] Ibid: 88

[12] ibid: 98

[13] The Lord Won’t Mind (Kindle ed: 13)

[14] Ibid: 43

[15] Ibid: 94f.

[16] Ibid: 191f.

[17] Ortiz op.cit: 296

[18] Ibid: 318

[19] One for the Gods (Kindle ed: Location 496)

[20] Ibid: Location 332

[21] Cited ibid: 429

[22] See my blog at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/06/11/he-came-each-to-avoid-the-eyes-of-everyone-who-wanted-him-the-gossips-said-he-refused-to-sleep-with-people-because-he-had-a-small-penis-the-leprosy-of-homosex/ The citation is from Andrew Holleran’s (1979: 15) Dancer from The Dance London, Jonathan Cape Ltd.

[24] Holleran 2022 op.cit: 15

[25] See – refs from The Lord

[26] Holleran 2022 op.cit: 15. In fact citing Ortiz op.cit: 345

[27] Ibid: 5019.

[28] Ortiz op.cit: 173

[29] Cited ibid: 177

[31] Ibid:416

[32] Ibid: 373

[33] Ibid: 417

[34] Ibid: 456

[35] The Lord Won’t Mind (Kindle: 38f.)

[36] Ibid: 141

[37] Ortiz op.cit: 211f.

[38] One for the Gods (Kindle ed: Location 5804)

[39] Ibid: 6033

[40] The Lord Won’t Mind (Kindle: 71)

[41] Ibid: 58

[42] One for the Gods (Kindle: loc. 1174

Thank you for this wonderful, incredibly insightful review of my book! I absolutely loved reading it, and I think your analyses of The Lord Won’t Mind and One for the Gods are brilliant. Please feel free to contact me if you want to continue the discussion.

LikeLike

Thank you. Your book is wonderful.

LikeLike