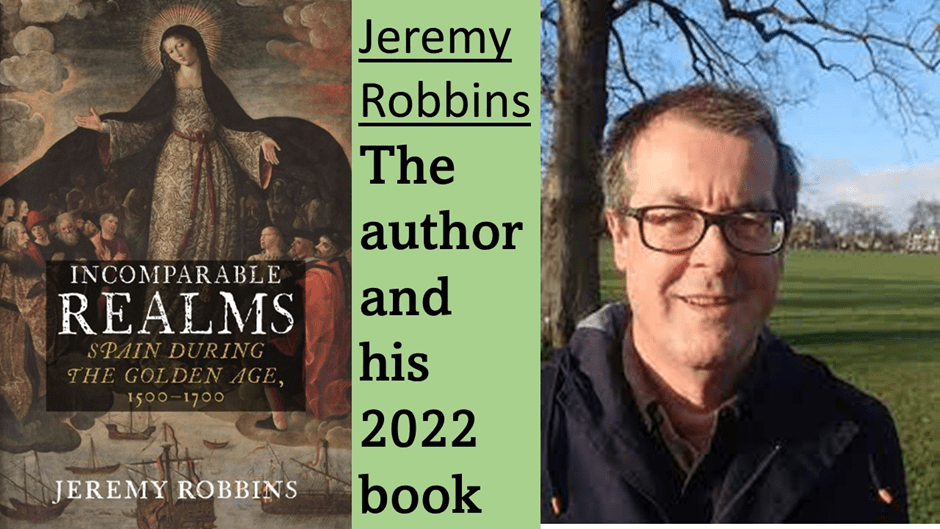

Comparing the Incommensurable: Concerning the Art, Politics & Culture of the Incomplete in Golden Age ‘Spain’: This is a reflective blog on a wonderful book by Jeremy Robbins (2022), Incomparable Realms: Spain During The Golden Age, 1500-1700 London, Reaktion Books Ltd: ‘… incomparability enfolds much that we encounter: at the heart of this lies incommensurability, the belief that so many of the binaries that structure mentality and worldview, are entirely woven together, and yet entirely antithetical’.[1]

The book and the man

My interest in Spanish art is of fairly recent flowering, and even then my Knowledge of the material leaves a lot to fill before I can say it is even adequate. It grew from the first opening of a Spanish Gallery of Art in Bishop Auckland, Country Durham, about which I blogged in October 2019 (there is a full list of my blogs based on this at the end of this blog), but it is and remains a queer and questioning interest, fascinated by the odd in Spanish art, which somehow meets all the norms of art but in some way or other queers them, raising issues additional to those offered by the culture of other nations. Is it me? I thought this as I wrote my blogs about experiencing the gallery. Suddenly I read a review, By Duncan Wheeler, in the Literary Review which praises a book on Golden Age Spain for its ‘measured approach whilst it ‘advances the original convincing new hypothesis that “… incommensurability reverberates as an issue across early modern Spanish culture”’.[2]

Looking at a range of issues which can’t be measure or compared in the same or even similar terms is surely the very essence of both the queer and the questioning as an approach, and here was a book that might do that. So read it I intended to do, though it sat at the base of my pile of intended reading for quite a little time. But having now read it, this book did not either disappoint nor make me question Wheeler’s judgement, for, if anything, he undersells what the book has to offer, though he is correct in seeing it divided on imperial Spain in its simultaneous appreciation of a consumingly fascinating cultural fertility, in writing and visual art whilst acknowledging the oppression of other racial and ethnic cultures it considered as exploitable in its own interests.

There is much in the book not only on the ‘imperial sins’ (as named by Wheeler) of the slave trade and colonial tyranny but of the necessity for Spanish culture to be as attractive as it was of persecuting and driving out of Spain not only Muslim and Jewish populations but of destroying the truth of that culture’s deep debt to both those cultures in medieval Iberia, wherein multicultural expressions of beauty were as great as one might find in the Byzantine marginal lands (Trebizond for instance).

For me the book does so much with the notion of the incommensurable and incomparable, showing that it is a feature of cultures that insist on the notion on non-communicating binary oppositions (even ones like male and female) that refuse to see the continua on which they exist as poles rather than as opposites. Such cultures, like Spain, are as conspicuous in invoking some kind of unnegotiable world of binaries as well as implementing cruel forms of ‘policing’ difference’, such as in Span and its dependencies (in Europe and the New World) the Inquisition. Robbins says that, in relation to advice to the King on whether it was appropriate to use a carriage when so many ‘commoners’ did so, ‘policing difference, here class difference, became a defining feature of Golden Age Spain’.[3] I think this is why I choose the piece of the book I choose to quote in my title from its concluding words. These words aren’t, as so often in academic books, a pretentious covering for a lack of demonstrable comparative analysis of different kinds of cultural experience in history and from so many domains, topics and angles.

I give the list of my blogs below to record how many of the themes and questions I raise in this from an amateur perspective are completely and satisfyingly contextualised in those analyses – not least because they cover understandings that seem discrete in themselves of painting, sculpture, architectural and interiors design, the literature that spans from the picaresque novel to the visionary Saint Theresa and St. John of the Cross, the introduction to whose poetry (with excellent contiguous prose translations) was a revelation to me. That is in part because, as a critic he can show you without appearing to do this what one loses even in good translation from even the most tired of techniques, such as rhyme or repetition, when we lose the original language. Here he is discussing how Juan de la Cruz (1542 – 1591) uses the phenomenon of ‘stuttering’ in oral language to show ‘precisely the human lack of clear knowledge of the divine’ or mystical experience.

By Anonymous artist 17C – http://enlargingtheheart.wordpress.com/2009/12/01/john-of-the-cross-the-soul-has-its-life-in-god/, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=10350023

Y todos cuantos vagan

de ti me van mil gracias refriendo,

y todos más me llagan,

y déjame muriendo

un no sé qué que quedan balbuciendo.

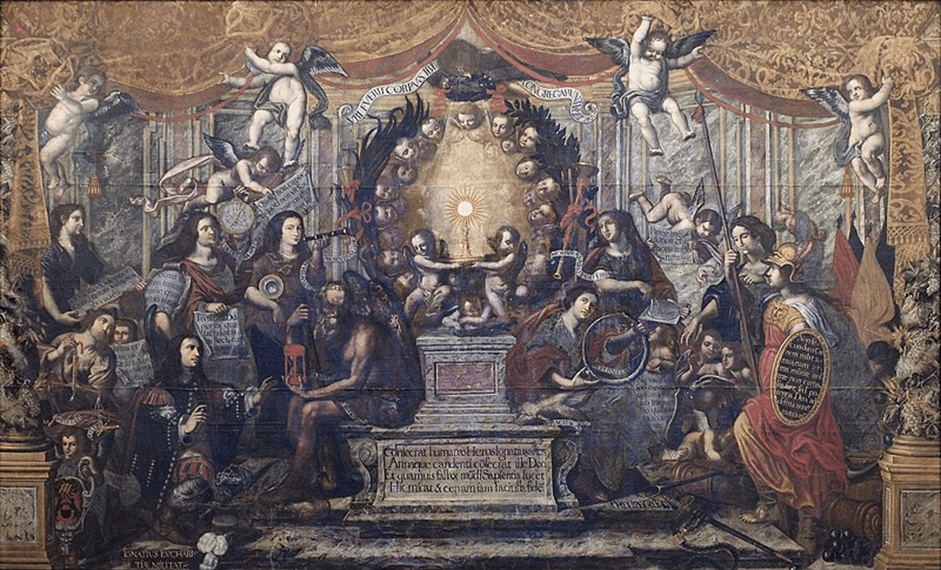

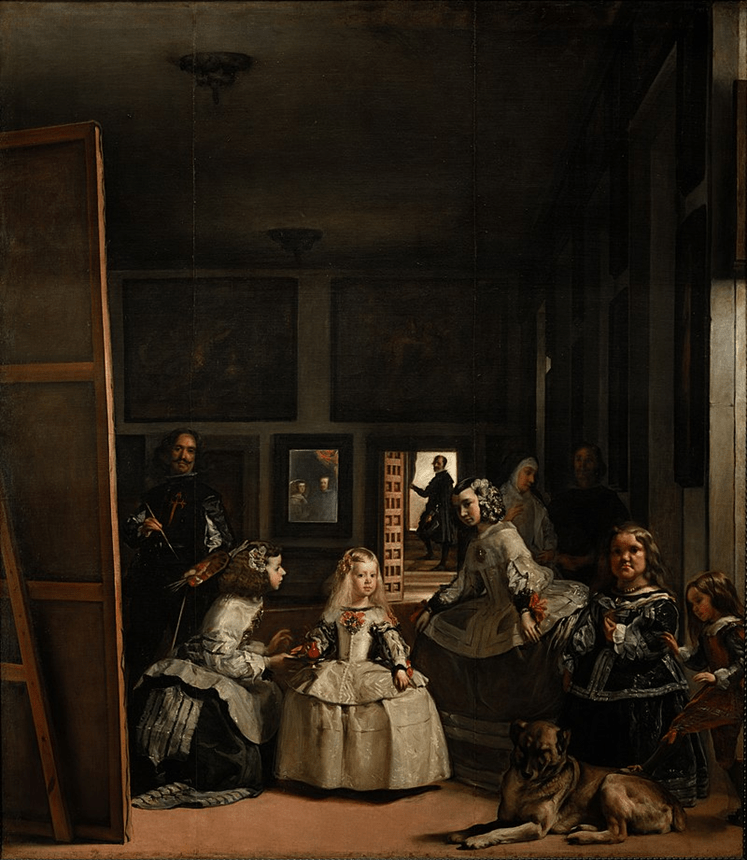

The ‘triple repetition of ‘que’ in Spanish to evoke a stutter’ is one merely ‘of sound not sense’ so that, at one level, Robbins says, ‘communicating perfectly’: yet naming the ineffable, the (in his translation’ ‘the certain something that they stutter’ and which leave Juan sensibly ‘dying’. [4] The absolute mastery of critical appreciation here passes between the summary of each art Robbins touches on, so that, just as here he links verbal techniques with ideas so beautifully and with nuanced effect, so he does in his analysis of the detail of Baroque trompe l’oeil (fool the eye) effects in painting which confuse the ontology of what we are seeing. This happens with effects on the meta-realities evoked in mise en abyme (work within a work effects) effects in Velasquez or Pereda.[5] Likewise, this applies to the use of quadratura (the use of images of built architectural columns or other three-dimensional architecture to show upward looking perspectives that fool one’s sense of visualised height and stability of detail.[6]

”Apoteosis de la Eucaristía”, de Felipe Gil de Mena (1603-1673). [:Category: Church of San Miguel and San Julián, Valladolid Iglesia de San Miguel y San Julián, Valladolid

The incommensurable binaries that that Spain combines – even in its geopolitical self as an entity, since it was half-the-same as Hapsburg dependencies in Italy and Northern Europe as well as those across the Globe in the Americas – are ideas of the one and the many, the divine and the worldly, eternity and the passage of time as if in a second, the King and his person in Spanish royal portraiture.

The fact that these equally present but incompatibly incomparable realities must be experienced today explains effects in art, Robbins says, such as those already mentioned where the facture of the work is part of its message – how the language and sound of a poem is created for instance or the elements of a fiction, like those of Cervantes, sustained or the visible facture of Las Meninas emphasised by tricks of mise en abyme and hard-to-locate spaces in mirror reflections.[7] And the of course, unknown to other than specialists of Spanish literary history, the self-referring meta-theatricality of the masques produced for Philip IV in Buen Retiro.[8] Likewise the odd dream texts of moralists like Quevedo and the disturbing queerness of polychrome statues – like life but somehow too like life to be other than showing how feeble life is in its terrible beauties.[9]

By Diego Velázquez – The Prado in Google Earth: Home – 7th level of zoom, JPEG compression quality: Photoshop 8., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=22600614

The exploration of binaries in the art, politics and religion of Spain is at its finest in discussing the famous example of the open set against the closed, because nothing was nearer to the use of the ‘religious imaginary’ to bolster Hapsburg ideology, an image of Spain as a multiple-state nation-Empire and its intriguing art and religion – with images as plain as day that seem still to shut their life and meaning away from sight whilst in plain sight. As Robbins puts it: ‘Was it a closed country with little direct contact with other peoples, cultures and views or a European and global power directly and indirectly engaged with the affairs of many countries and peoples’.[10] In fact it was both!

Still lifes are a wonderful form of art that opens up and closes down the world and this book puts their prominence in Spanish and Hapsburg art into context here, for the first and best time for me. Robbins says that in such art:

In this focusing on the inconsequential and the quotidian, there is an intense gaze at the here and now, and it is the intensity of that gaze – that also brings into play otherness and thus a feeling of immanence.[11]

This is most perfect, though not easy to read (though personally I love this dark style of the precise obscurantist, of a Zurburán still life, like that below. But doesn’t it also incapsulate Don Quixote.

Picture credit: Francisco de Zurbarán. A Cup of Water and a Rose. About 1630. © The National Gallery, London Available at: https://www.masterpiecefair.com/blog-details/121/object-of-the-month-still-life-with-a-cup-of-water-and-a-rose

That sight and the ability it has to deceive us more ably than the other senses becomes a key motif in this art must have been noticed before Robbins but never so well synthesised as a thesis that sums up Golden age Spain but also some other mysteries in modern history, such as the much less interesting mind of a TERF like J.K. Rowling. Hence th interest in ‘mirrors’ or even portals that might be mirrors to which a whole chapter of the book is dedicated and which opens by looking at Philip IV’s Salón de los Espejos (Hall of Mirrors).[12] But even better than that insight is that such obsession masks an interest and perhaps even stimulates it, in the haptic. We so want and need to touch what we see in Spanish art. Ribera stands opened up by such an insight whose touch even invites penetration.

Because I puzzled about the iconology of the Hapsburg fascination with the Golden fleece in my blog on royal portraiture, I was delighted to read this book if only, but it wasn’t if only, because it fully explicated the iconology in a way that opened the closed in its meanings somewhat so that one saw how its ‘imperial and symbolic dimensions’ married, together as does the pagan and Christian imagery that gets us there.[13] This is obviously a great book. It is demanding but demanding because it synthesised vast resources of critical inquiry. I love it even for reasons others may not – for I find a music in its love of long abstract words, which is the music of philosophers if not of angels, of scholars with no sense of how to touch on the real in my other world of social work but with something to tell it, if they have time to listen (which they probably do not). I found even writing this an escape.

Rodrigo de Villandrando (attrib.): Portrait of Philip IV wearing Golden Fleece necklet passed down the line to him from Charles V. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Rodrigo_de_Villandrando_%28attrib.%29_-_Portrait_of_the_young_Philip_IV.jpg

All the best

Steve

Spanish Royal Portraiture

Spanish polychrome sculpture:

Spanish still life:

Ribera

Murillo:

El Greco:

Juan van der Hamen y León (1596 – 1631)

The Bishop Auckland Spanish Gallery opens:

[1] The quotation is edited in tense and contains omissions (some of them being long). Otherwise it is from the concluding paragraph of Jeremy Robbins (2022: 308), Incomparable Realms: Spain During The Golden Age, 1500-1700 London, Reaktion Books Ltd

[2] Duncan Wheeler (2022: 34) ‘Don Quixote Meets Don Juan’ in Literary Review Issue 510 (Aug. 2022), 34f.

[3] Jeremy Robbins op.cit: 15

[4] Ibid: 181

[5] Ibid: 306 for instance

[6] Ibid: 291 on the fictive retablo in a church in Vallodolid by Felipe Gil de Mena.

[7] Ibid: 56f.

[8] Ibid: 118

[9] Ibid: 185ff.

[10] Ibid: 250

[11] Ibid: 151f.

[12] Ibid: 273ff., Ch. 8

[13] Ibid: 44f.