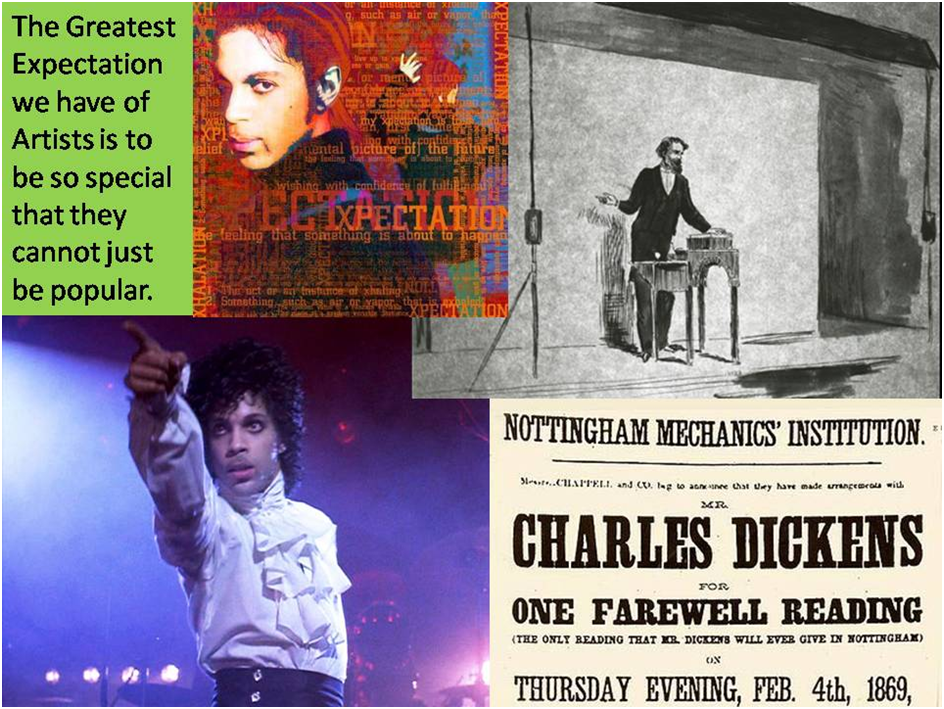

What do Prince and Dickens have in common? A blog on why Nick Hornby is right to look for the answer to why we cling to the notion of individual genius in remarkable comparisons between different artists. A blog on Nick Hornby (2022) ‘Dickens & Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius’, Penguin Random House UK. A blog for Prince’s princely fan @JustinCurley4

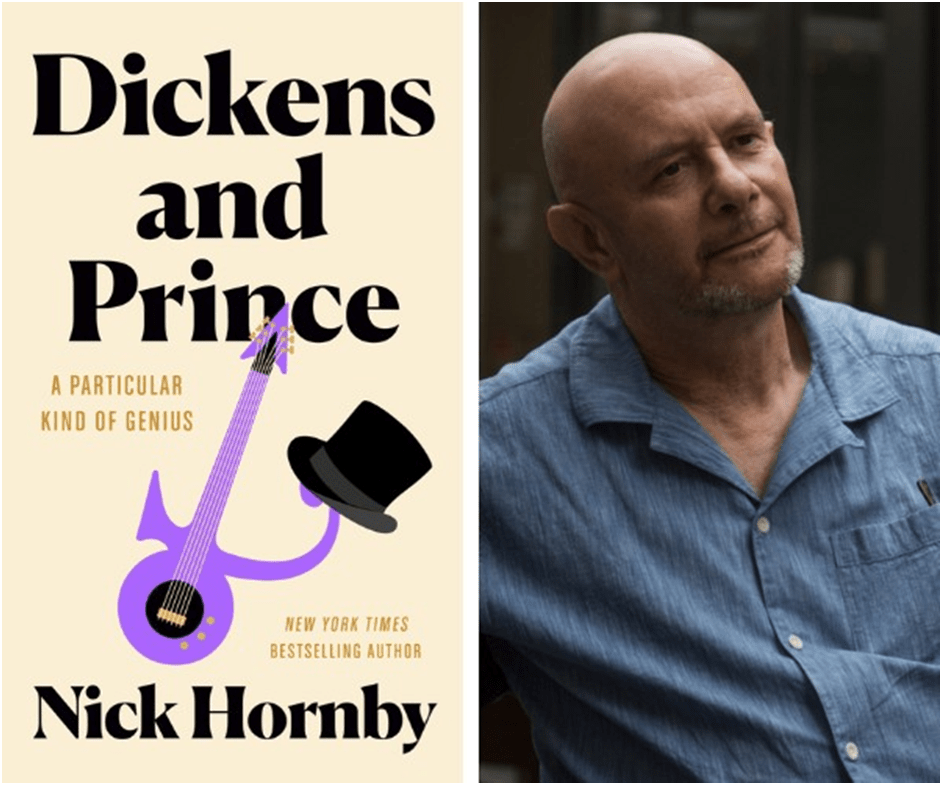

The beautiful UK book cover

This is not a book review for Fiona Sturges has already written in The Guardian all I could want to say about the way in which this book needs to be evaluated and enjoyed. Her central insight is worthy of long quotation so here I go:

Most important is what their lives and work tell us about creativity, and it’s on this that Hornby is in his element. From his early days writing about football (in Fever Pitch) and music (in High Fidelity), the author has long been fascinated by the transformative impact of culture, so it’s natural that his ruminations on Dickens and Prince should cause him to reflect on his own status as consumer and creator. … .

Pointing to Dickens and Prince’s vertiginous rise to fame, he upends the theory popularised by Malcolm Gladwell that it takes 10,000 hours to master an art – Dickens had “been writing for the Gladwell equivalent of five minutes before Pickwick … He was great and successful more or less immediately.” Elsewhere, he articulates with a fervour presumably born from experience what it is to fear failure after enjoying a major success – “People have their moment in the sun, and then the sun moves on to somebody else. Our careers seem built on nothing – words, ideas, sand” – and reflects on the ways artists can communicate from beyond the grave. The photos of Dickens and Prince that adorn Hornby’s office wall provide the impetus for him to work harder, think bigger, do better. “Whatever you do for a living,” he notes, “that’s something you need to hear every now and then”.[1]

In the end this book is indeed about the necessity of figures who model ‘genius’ in order to make it worth the effort to survive. This is a lesson I learned from my best friend, Justin Curley, well before he pointed me to this book. It’s a lesson that has helped me shave away the material that endears to what we perceive as greatness in an artist, a kind of creativity that improves us, without requesting that we merely imitate its example, and thus makes nonsense of the ideas of someone like Malcolm Gladwell (in his book Outliers) who indicates, at least according to Hornby, that there is a recipe for ‘genius’ in art of all kinds. [2] If there is, it isn’t that punched out by the academic institutions of continual revision of works that are slowly delivered and never motivated by life accidents – like the action of publishers (American ones in particular in Dickens’ case) or record producers (Warner Brothers in Prince’s case) who take advantage of one’s potential as a cash cow. Likewise literary or music criticism dogged both genii in our comparison rather than cultivated them in Nick Hornby’s account. Instead, he favours the views of ‘psychologist Dean Keith Simonton’ that talent ‘is “best thought of as any package of personal characteristics that accelerates the acquisition of expertise”’. [3]

Note that Hornby does not deny the hard work that goes into making the ‘particular kind of genius’ which interests him in both of his chosen artists. Both Prince and Dickens worked phenomenally hard and phenomenally quickly in response to all kinds of different motivating factors. Hornby says himself that his book is ‘about work, and nobody ever worked harder than these two’.[4] However, I think if you enjoy this book, which I definitively did, it will not be because of the praise of hard work but because of its perpetual wondering about what makes this ‘particular kind of genius’ other than work. And in the process issues like the desire for popularity on the one hand and endurance in time, even after one’s death, and the patterns that sometimes pulls these motivations apart, as if they are incompatible, and yet sometimes, at least in these two careers, brings them together are puzzled over as if that is all one can do with these motivations.

Perhaps that is because desiring either popularity with the audience of your own time, some kind of optimal enduring immortality or both together are in fact irrational desires – there to plague their bearer into defining their genius by constantly working it out of their system into objects that speak to the desires of others in particular ways, and often in different ways for different persons. Speaking of those two artists the question of ‘what they did with’ their talent and acquired expertise is nearly the same as wondering if that same talent, and the work drive it inspired, could ‘damage them in some way’, knowing where that talent ‘came from’ nearly the same source as our desire to know, ‘Did it kill them?’ [5]

This book’s narrative compels because of its open-ended questions for which, in truth, there can be no answer. This seems unsatisfactory to critics like Sarah Ditum in The Sunday Times, who thinks the book far from being ‘totally compelling about its reasons for yoking these two artists together’.[6] Even less mealy-mouthed is Michael Donkor in the i newspaper:

When Hornby’s personal attachment to his material recedes, unfortunate questions stubbornly haunt the text: what is the point of bringing together these artists? Is this book more than a stocking filler with intellectual pretensions?[7]

Perhaps this is so but in my opinion the book taps the kind of feelings that avid consumers, as well as producers, of art objects have that suggests great art touches on something much larger than what can be accounted for in merely rational terms and thus is bound to leave dissatisfaction in its wake as well as a sense of overwhelming significance and power. Sometimes critics seek rationalisations where they miss some quality of the writer’s experience being much less clearly communicated. I can only suggest this before moving to a brief and perhaps inadequate description of the form of this short book.

Dickens & Prince attempts to look at biographical themes that span both lives considered in order to seek out the link between the self-destructiveness in the artists to their genius, since these qualities seem yoked together in them. Each theme offers its different way of making this link for each artist. The chapters on ‘Childhood’ and ‘Women’ respectively and together are extremely powerful tools in this endeavour. It is not just because both had highly broken childhoods illustrative of abandonment, anxiety about deep attachment and the illusions that foster a non-existent sense of ‘security’ in the world but that they both explored these states of anomie in art, regardless of its quality: in Purple Rain for Prince (for my early but unsatisfactory blog on this use this link) as a start and, for Dickens, the path that forms from Oliver Twist to David Copperfield and Pip in Great Expectations. Art builds personae in all of these cases, although quite unstable personae, out of inordinate and exceptional passion speaking out from a very young age in their acts of gluttonous consumption of the art of others (good and bad) that will be the building blocks of their expertise: ‘Those kids, the ones destined for recording studios and auditoriums, are self-selecting’. [8]

Greedy passion for sex (with women in both cases) was ‘their weakness’.[9] Hornby delights in dubbing Prince a ‘heterosexual man’ who so embodied ‘sex’, onstage and on record’; that, for his audience, also suggested that ‘whatever sex was to you was fine by him’. [10] Both were destined to be ambivalent about women – evoking reverence whilst complicating any ‘reality’ required to see women’s lives as what they were to themselves rather to men who needed them to fulfil too many functions of their appetite for the display of varying emotion and self-identification as well as sex. I would personally evidence the fact that Dickens revelled in performing the role of Nancy murdered by Bill Sykes and loved older women as characters (as Hornby says too) but was hopeless at young women who intended, unlike Little Nell, to live. [11] As for Prince: ‘In the song I Will Die 4 U … Prince says he is neither a woman nor a man’. [12]

Detail of the logo on Prince’s bike in Purple Rain

Other chapters take themes that disregard some obvious difference in the times in which they lived and the opportunities peculiar to them (especially that on ‘The movies’ which inevitably deals with artistic creations based on Dickens’ work after his death). The chapter works for me, however, because it insists that even if an artist like Dickens cannot ‘undergo personal transformation’ as Prince did in Purple Rain, because he is dead already before films of his stories were conceived, he can be changed in the heads of the consumers of his creative productivity, as Dickens was by Lionel Bart’s Oliver! : ‘and, as a consequence, people got them wrong’.[13] Another fine chapter makes brilliant analogy between the relationship of both artists to the capitalist enterprises which managed their access to income both contractually (even in the absence of contract as with American publishers for Dickens), even in Hornby’s own case. His forebears make it clear to him that it is the death of substantive art if it fails to adapt, and instead allows itself to be absorbed into the perfectionism demanded by team creative processes: ‘Perfectionism here means the act of doing things over and over again until you’re sick of them’. [14] Dickens was better he thinks writing under pressure and without time for overmuch revision because of the instability of popular serial publishing. [15] Prince was more ambiguously creative, in for instance the invention of his female alter-ego, Camille, when he was pushing out songs – many of which, far from being over-polished team production pieces, never ‘really cohere into a unified whole; even now it’s possible to come across a great song that you’ve forgotten about because it doesn’t seem to belong’. [16]

The END of the book deals with the bodily deaths of both artists and it is beautiful, I think. What it is about is how the work we do in our life persists or does not persist, and in what form in peoples’ minds. It’s also about whether such persistence and constancy at all matters to anyone. And perhaps they don’t. What does matter is that we find models that make us continue to strive ourselves to something better and something that is quantitatively substantial as well as qualitative good enough to matter that it can be improved during the relatively short time allotted for our work whist we live. Their message is, Hornby says: ‘Not good enough. Not quick enough. Not enough. More, more, more’. As he further goes on to say making it matter (our life and times that is) matters more than whether we ‘were happy’ or ‘are crazy’. It matters far less to want art that is improving or civilising than to want more and more art, because only the latter desire triggers the opportunity for genius, Hornby seems to say. Indeed seeing art as a mission that improves is too often he suggests in a footnote ‘obtuseness, snobbery … and confusion’ that only needs the idea of populism as a giant windmill to foolishly and romantically tilt against.

I just do not know what I think about that idea yet. But I am awfully glad the argument has been made. Read this lovely book for yourself. It seems to chime with an idea that emerges in an interview about this book with Lisa O’Kelly in The Guardian, where Hornby says about his own future in relation to his models in this book as he discusses a shift from novels to TV scripts:

… if you look at the history of writing, writers tend to shift to wherever the work is. In the 1950s everybody wanted to be a playwright but it’s very hard to imagine if a writer had any choice of career at the moment that they would start with the theatre. Same with fiction, I’m afraid. If you want an audience then the place to go looks like it’s TV. [17]

I do prefer the USA book cover even if it’s less classy. Available at: https://charleston.boldtypetickets.com/events/128699669/nick-hornby-literary-legend-and-rock-star?ref=website

All the best,

Steve

[1] Fiona Sturges (2022) ‘Dickens and Prince by Nick Hornby review – cultural greats collide’ in The Guardian online (Fri 28 Oct 2022 09.00 BST)

[2] Nick Hornby (2022: 26) ‘Dickens & Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius’, Penguin Random House UK

[3] Cited ibid:15

[4] Ibid: 91

[5] Ibid: 9

[6] Sarah Ditum (2022) ‘Nick Hornby pits the sex-funk god against the novelist’ in The Sunday Times Culture magazine (30 October 2022, p. 32).

[7] Michael Donkor (2022) ‘A bit like listening to a pub bore’ in i online (October 27, 2022 1:33 pm (Updated October 28, 2022 11:39 pm)

[8] Nick Hornby 2022 op.cit: 29

[9] Ibid: 67

[10] Ibid: 72

[11] Ibid: 75

[12] Ibid: 71

[13] Ibid; 39

[14] Ibid: 47

[15] ibid; 49

[16] ibid: 48

[17] Lisa O’Kelly (2022) ‘Interview with Nick Hornby’ in The Guardian Online [Sun 16 Oct 2022 07.00 BST]

2 thoughts on “What do Prince and Dickens have in common? A blog on why Nick Hornby is right to look for the answer to why we cling to the notion of individual genius in remarkable comparisons between different artists. A blog on Nick Hornby (2022) ‘Dickens & Prince: A Particular Kind of Genius’. A blog for Prince’s princely fan @JustinCurley4”