‘Queer people have a particular stake in the question of paradise. …. not as a false paradise, or a paradise lost, but as an extant changing site, alive and livable, suspended in the present of a shared moment, and still ripe for rewriting’.[1] Do places have biographies as well as histories, inner lives and the stuff of changes that occur in time tempered by reflection as well as circumstance? The case of Fire Island as see by Jack Parlett in Fire Island: Love, Loss and Liberation in an American Paradise, London, Granta Publications.

My copy of the book.

That places have biographies is already an idea that is renascent in the culture of art criticism, particularly when the place characterises a group that can be in some way used to illustrate the life and development of both group and place. And in the best and the worst examples of this trend in art history are, for me, illustrated by Gerald Massey and Mary Ann Caws respectively.[2] I have already spoken in a blog on Massey’s wonderful Queer St. Ives (use this link to find that blog) of how groups associated to places have not only been confined to the representatives of self-styled artistic movements or trends (as at Pont Aven in visual art or Worpswede for literature (Rilke for instance) and visual art) but also psychosocial categorisations of people around issues like race, sexuality or gender. Here is a quotation from that blog in which I treat Massey’s characterisation of St. Ives an exemplum of best practice wherein the cusp between different kind of social group (including voluntary ones around definitions of art) are explored. I begin this paragraph by illustrating a:

… context in art history against which we might evaluate the innovative quality of Ian Massey’s group biography of a part of the St. Ives ‘gathering’, in Caws’ term. For queerness and ‘otherness’ is at its heart. Work for Massey’s project began as a biography of John Milne but, as he says on his Art UK page on the book: ‘Over time I realised that I was not only writing a biography of Milne, but also what amounted to a previously unexplored queer history of St Ives, in which many subsidiary queer characters became interwoven in its narrative’.[3]

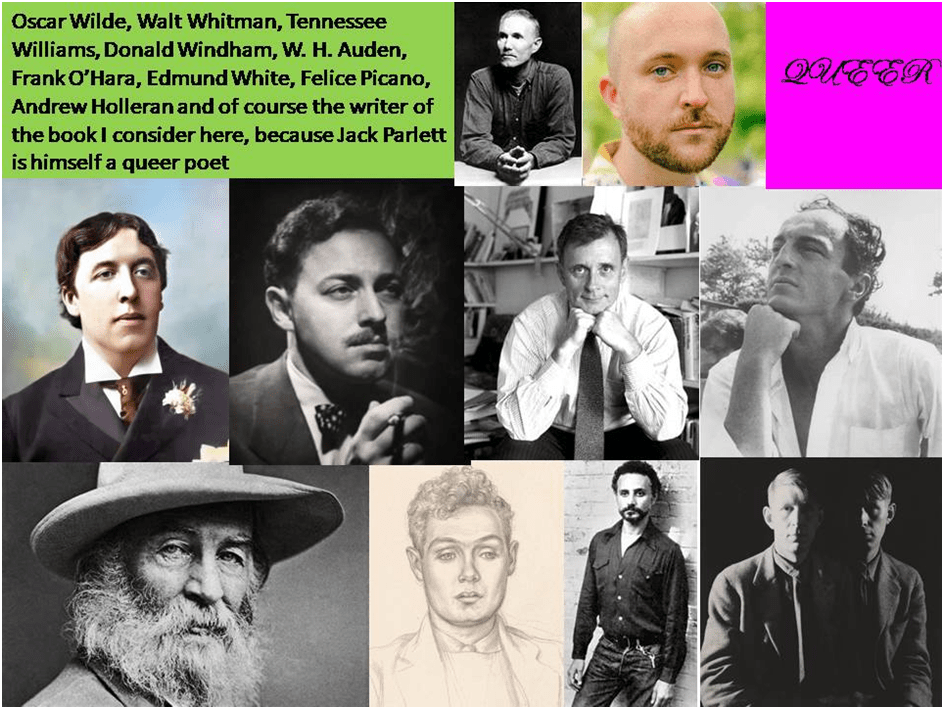

The case of Fire Island may suggest already a panoply of queer lifelines well woven into the life of the place for much of its history, even if for only a portion of its geography. However, artists are also well represented in this history – if mainly literary artists. Fire Island’s history touches on the history of queer figures and icons such as Oscar Wilde, Walt Whitman, Tennessee Williams, Donald Windham, W. H. Auden, Frank O’Hara, Edmund White, Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran and of course the writer of the book I consider here, because Jack Parlett is himself a queer poet as well as literary historian and critic.

The book tells potted biographies of the writers above and many others (including Carson McCullers, whom I should have included in my gallery above, had I not decided to focus on male writers and ones I knew well) but these stories do not speak of a place that is only a reflection of them as people or writers. Indeed, each of these people has a very different relationship to the island and its other inhabitants. Some lived there for a significant period, others only as the most temporary of visitors. For Donald Windham, perhaps the least remembered of these men, ‘Fire Island remained a home, a place of retreat, where he could go and write and take stock of the cultural world he moved through’.[4]

Though Windham must be considered a near-permanent resident in his late adult life, Parlett here shows that writers rarely situate themselves either as a persona who may appear in their writing or as a writer about wider human life entirely in relationship to one place, or even sometimes one time. They take the wider world with them to Fire Island and take what Fire Island gives them, which may be just the time for reflection, back into the wider world. Sometimes what they take back is a vision of a more open queer sexuality that the evidence from Fire Island may warrant. Whitman was born there and also wrote a poem entitled Long Island is A Great Place: it celebrates though ‘curious and original characters’ (including ‘wrecks and wreckers’) from its curious maritime life rather than queer sexuality per se. It may be wishful thinking to attribute the beaches in Whitman’s most homo-erotic reflective poetry to the beaches of Long Island. Wilde may never have visited the town of Cherry Grove on Long Island except in the wishful myth of Fire Island lovers.[5]

However, later in its island life Parlett is surely correct to see a pointer towards to the notion of ‘chosen (as opposed to biologically, socially or legislatively imposed) families’ in the relative freedom of some lesbian alliances set up there such as that of Janet Flanner and Natalia Danesi Murray in the 1930s. There is also the three-way queer relationship between Margaret Hoening French, her husband Jared French and Paul Cadmus, the painter of The Fleet’s In (who knew themselves collectively as artists under the name PaJaMa (Paul, Jared & Margaret): Parlett says: ‘Art critics have referred to them as the “Fire Island School of Painting”’.[6] There are interesting chosen families made by artists and other tolerated individualists throughout the history of Long Island but perhaps that does not distinguish its social history.

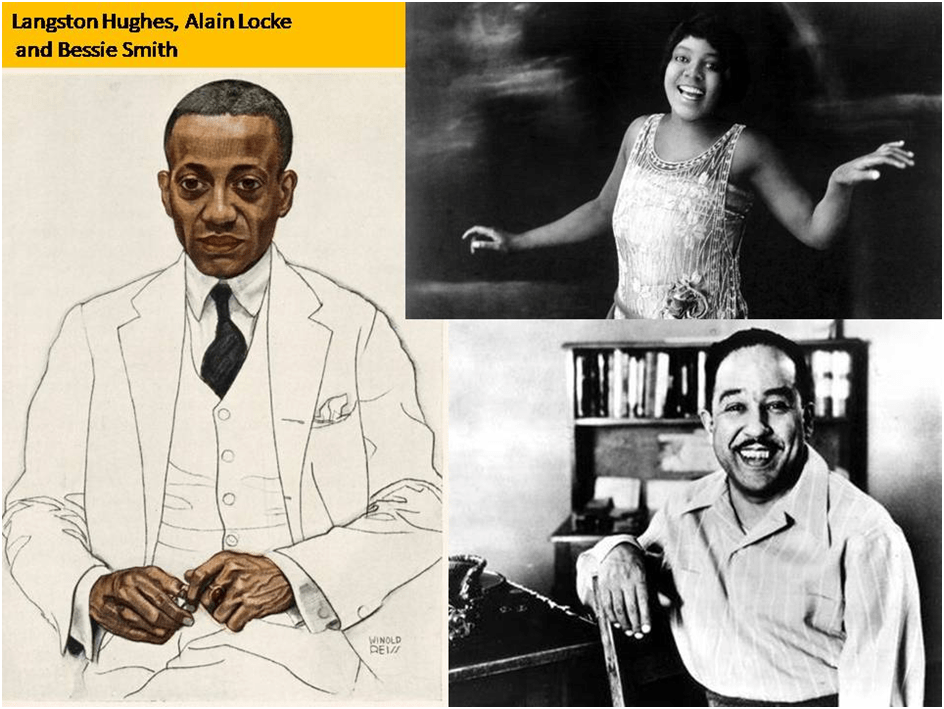

My interest is in the way these literary biographies intersect other histories that apply to larger social groupings, especially queer groupings as the central section and towns of the island became a queer resort as well as a queer retreat for the relatively famed. In 1948 Auden wrote a ‘satirical, moralistic’ poem on the place ‘titled “Pleasure Island”’. It is a place he insists that proves that ‘“it’s possible to believe in a thing and ridicule it at the same time”’.[7] For most of its history the social history of that section of the island (notably the towns of Cherry Grove and the Pines and the dunes between the towns that have become known as the ‘Meat Rack’) was also ‘exclusive’ in terms of class, social status and income, ‘race’ and, to some extent gender. There may have been moments where the mix of sexual and black cultural and social politics associated with the Harlem Renaissance could counter this claim in the form of figures like ‘Langston Hughes, Alain Locke and Bessie Smith’.[8]

But in the queer-politicised 1970s, Fire Island was banned as a topic by the ‘gay anarchist newspaper Fag Rag because of both its association with the commercialisation of gay life and, in the eyes of many New Yorkers according to Parlett, it felt ‘retrograde in its exclusivity’. A trope character of the period is the “Fire Island gay”:

He is anywhere between twenty-five and fifty, … toned, groomed and moneyed, … he puts in hours at the gym for the necessary body. He likes to party. … Race is one of his blind spots. … he holds a number of problematic views when actually pushed on his beliefs. He is the White Gay par excellence.

And, we can add to this physique-and-body conscious trope, a phenomenon often noted by the Violet Quill writers (Felice Picano, Andrew Holleran and Edmund White), that he is obsessed by penis size (use the link to see my explanatory early blog). Of course, all cases tropes representing large groups of people are fictions and this trope too, according to Parlett, ‘doesn’t exist’ other than to characterise the worst traits of the everyman we feel we have met there, though we could not name even a single real instance. [9] The trope persists however well into the twenty-first century. I think Parlett is at his best in when he makes it clear that the characterisation of the life (the biography) of place is not the biography of a trope like this any more than it is any one or even an aggregate of the literary lives he finds himself unfolding during Fire Island’s story. I anticipate my argument here to say that a place can have inner and outer lives and is like a person (while it is definitely not one) because of the extraordinary interactions between these lives – contradictory in themselves – but throwing up even more contradictions in the process of their developmental history.

A place like a person exists in retrospect and prospects rather more than in any present moment, for the latter is itself and amalgam of the former two: memory and desire, past and future, investments in inherited values and future potential. Paradise is a metaphor then of such investments – in main a fictional retelling, but not of a thing lost but an early insight into alternative realities and a continual sense that those alternatives might become an emergent reality for us, Parlett’s prose continually plays with this idea, not least in the quotation in my blog title.

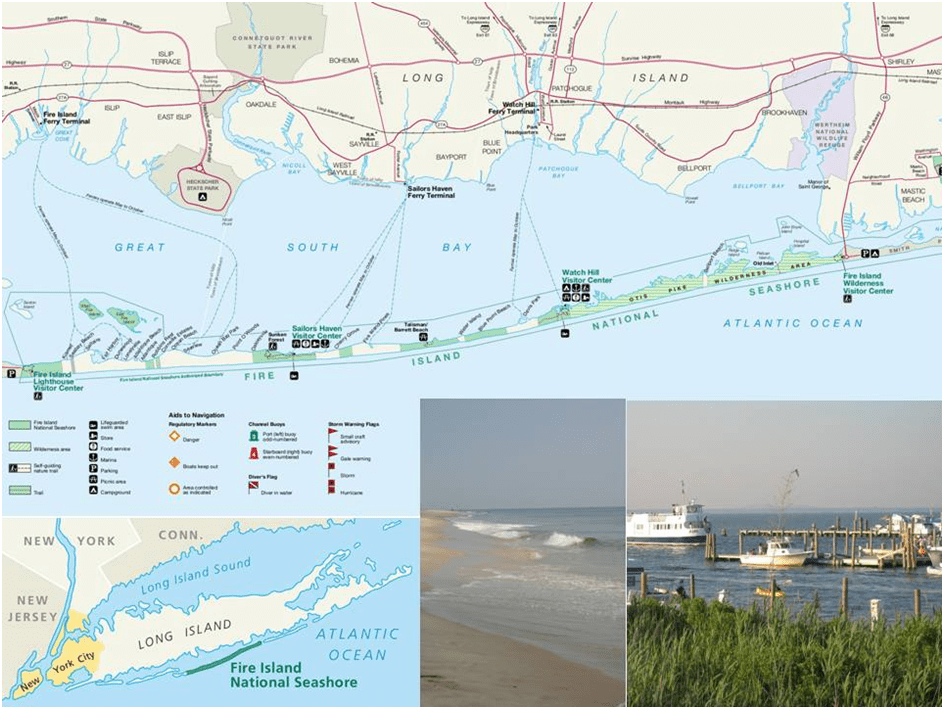

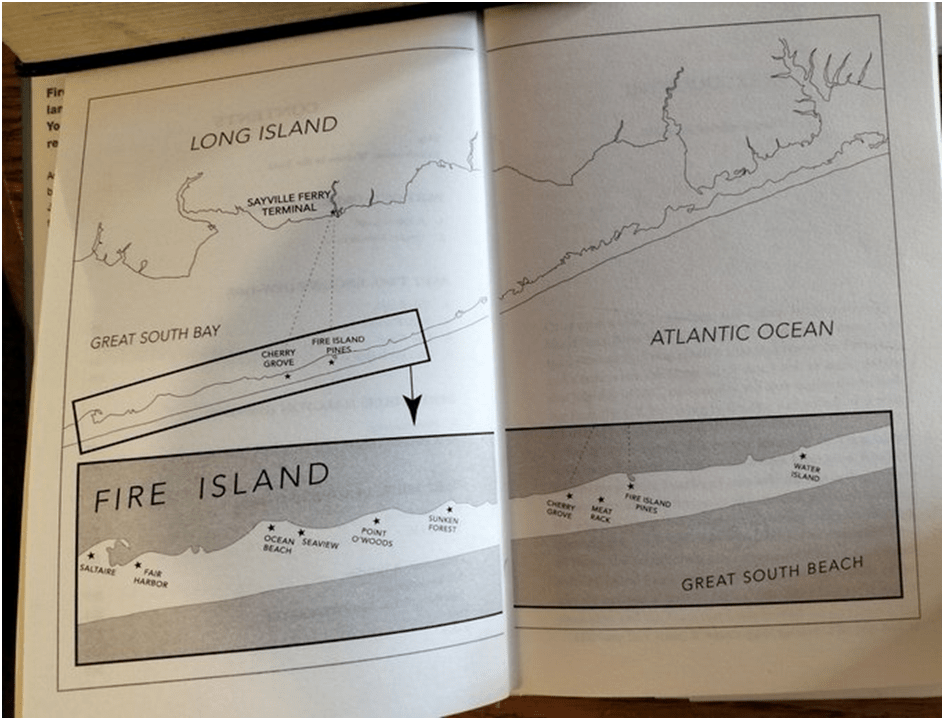

And the time in which a place lives is also, like that of a person, one with a physical framework or skeleton and various modes of self-realisation as ideas, emotions and their externalisation as that which clothes the physical, to use Carlyle’s metaphor from Sartor Resartus. These modes metamorphose through time, their themes played out in the diverse micro-biographies that recur through the book. The living physical framework of the Fire Island persona is the skeletal protrusion that is the island, conceived as a living person itself. Hence topographical elements matter: A colourful map might help us here.

However, I think Parlett’s line map even better, which shows that colour isn’t everything.

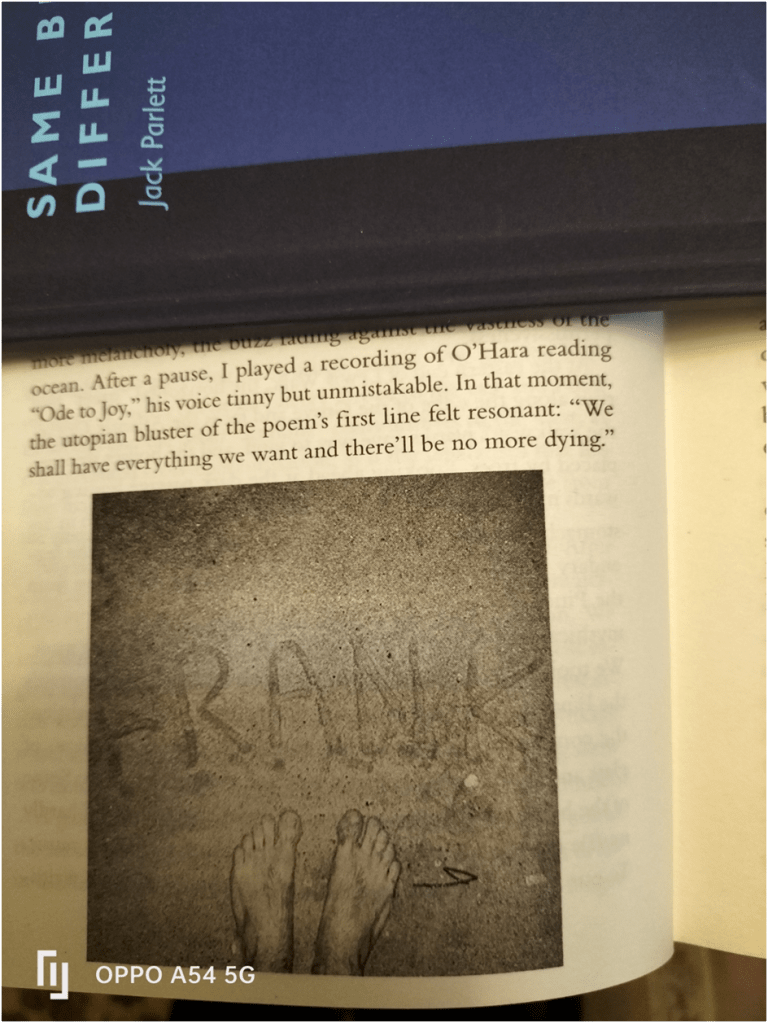

The Introduction describes this topography’s physical characteristic in terms of its visible signs permanent and transitory, including those socio-cultural ones temporarily inscribed on them like Parlett’s inscription into the sand of the name of Frank O’Hara (reflecting the same act with the name of James Dean by O’Hara himself). The act is commemorated with a picture of the author’s feet (see below). The photograph feels to me to link Frank O’Hara’s young death not only to James Dean but to John Keats: For ‘here lies one whose name is writ on a beach’s sand’, rather than, in Keats’ case, ‘writ on water’. The first chapter dives (if into the shallowest of waters) into the possible geological origins and the cultural gatherings included in the etymology of its name only to come up with a blank for the ‘tantalizing origin story’ it sought because there are, for the etymological origins at least, no genuine clues in ‘historical record’. From the beginning of its life, Parlett stresses, reconstructions of the island’s origins are significant, and will become important again in thinking of the prospects for its future, because Long Island is vulnerable to the accidents of climatic change. It was formed, we think, as a result of glacial action and projections of its future see it at risk of major flooding and possible submergence by the end of this century.[10] Its future prospects are, thinks Parlett, ‘a cruel metaphor for the evanescence that makes it special, the sense of a halcyon summer whose pleasures defy its brevity’.[11]

Parlett muses that community politics of a serious kind will rise to the threat to the island’s future, but that it will require a rather deeper sense of what gives life meaning in those communities than formerly. And this is true also of its status as a refuge for queer life; for markets are not respecters of, in the long duration of history, short-lived refuge of minority life-options: ‘it may feel like an unshakeable fact that the public beaches of the Grove and the pines “belong” to queer people, culturally speaking, but that status is not codified or legally protected’.[12] Parlett is in some degree hopeful because the signs that Long Island ‘belonged’ (again culturally speaking) to a well-heeled clique of white queer men are yielding to a wider community armed with ‘diversity and antiracism’ initiatives, spawning sub-groups of activism for Black and Brown people and reflected in art too, such as in Lola Dash’s installation We Are Here: The Unsung Fire Island, about which Parlett has already written at greater length for BBC NEWS online.[13]

This is the sign of the deeper personality of Fire Island explored by Jack Parlett, as a kind of being that reflects on its obscure origins and is worried about its future. This kind of thinking in people and groups, I think, either falls into denial, succumbing to the desires prompted by its external beauty (easily available because transferable and commodifiable fleshly pleasures) or begins the process of change; first in contemplation and then beginning, ever so slowly, to act to inspire change that validates its being in the deepest and most enduring cultural values of association achieved without ownership of one being of another. The values I mention include empathy, love, companionship – even the ‘kindness of strangers’ – and community. I sense this in the best of Parlett’s wonderful poetry too and I will try and illustrate this as I attempt to understand why and how he thinks that ‘Queer people have a particular stake in the question of paradise’. [14]

I don’t feel capable of teasing out the arguments for this that Parlett gives following the quotation I cite immediately above. Hence, I will put it in another form, suggested by his poem Ensemble, Ensemble. Growing ‘up queer in a heteronormative world’ robs a person most of the stuff of communal relationships: for all of the available heteronormative ones exclude the queer from its own limited world and values. Return to community and to values of enduring bonds by queer people is done then, according to Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick as cited by Parlett, “with difficulty and belatedly” and done in a kind of patchwork way which knits itself together “from fragments a community, a usable heritage, a politics of survival or resistance”. [15] These fragments from the dominant culture became strangely extended in meaning.

Let’s take the particular example in Ensemble, Ensemble, of the concept of the club happy hour to create an example, apparently trivial, of what might pass in a fallen world for paradise – a fixed duration where pleasure seems cheap because alcoholic drinks are discounted. The bathos in this fact is part of the way gay ghettos fragment the trivial from everyday heteronormative experience, making it an emotionally loaded concept for queer people otherwise drained of ‘natural’ communities for socialisation.

We know only this; that Happy Hour is unassailable,

that curiosity in another is not for another hour, but this

hour. Not for another place, but this place. …[16]

I don’t think the term Happy Hour in these lines carries the kind of weight that makes the views of ‘we’ (I take this ‘we’ to be the queer ensemble) merely ironic or belittles the people relying for a brief time on that pastiche of a ‘paradisal’ moment. It symbolises in real life as well as in a poem a space and time where communal joy seems possible, a thing snatched from a world otherwise hostile to the communal in queer world – ‘tolerating’ it, if at all, only in private invisible rather than public visible spaces. We need as a community to make for ourselves spaces and times for bliss. Perhaps Fire Island is one such. It stands not for the reality of paradise but the need in queer ‘community’ to make up a paradise:

…. not as a false paradise, or a paradise lost, but as an extant changing site, alive and livable, suspended in the present of a shared moment, and still ripe for rewriting’.[17]

And it is in writing and rewriting up our special times and places that makes of them a meaningful attempt to see potential in our lives that mainstream and conventional values otherwise marginalise. Hence Ensemble, Ensemble is a poem about writing poems. Fire Island is a litany to many rewritings of itself that have helped it to create a character that spans them all and is the sum of the differences between these different writers, adding up to the motive for the memory and desire inspired by that space, because: ‘discovering Fire Island’ is like ‘an epiphany’: a revelation of the spiritual in the everyday. [18]

Do read this book (and the poems in Same Blue, Different You too) for both together constitute an epiphany and an explanation of why such experience is necessary if a deeper queer community is to survive its emergence.

All my love

Steve

[1] Jack Parlett (2022: 217, 221) Fire Island: Love, Loss and Liberation in an American Paradise London, Granta Publications.

[2] Ian Massey (2022a: 29) ‘Queer St Ives and Other Stories’ London, Ridinghouse & Mary Ann Caws (2019) Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism London, Reaktion Books (My blog on Mary Anne Caws is linked here).

[3] Ian Massey (2022b) Art UK webpage on Queer St Ives and Other Stories Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/queer-st-ives-and-other-stories

[4] Jack Parlett (2022a: 59) Fire Island: Love, Loss and Liberation in an American Paradise, London, Granta Publications

[5] Ibid: 32 – 36

[6] Ibid: 51

[7] Ibid: 85

[8] Ibid: 46

[9] Ibid: 209

[10] https://sites.williams.edu/geos101/mid-atlantic/geological-history-of-long-island/

[11] Parlett 2022a. op.cit: 221

[12] Ibid: 220

[13] Ibid: 220 & Jack Parlett (2022b.) Available at: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20220618-fire-island-the-allure-of-americas-great-gay-paradise

[14] Jack Parlett 2022 op.cit: 217.

[15] Sedgwick cited ibid: 219

[16]Jack Parlett (2020: 29) Ensemble, Ensemble, line 15ff. In Jack Parlett Same Blue, Different You Cornwall / Wales, Broken Sleep Books [author’s italics in quotation] .

[17] Jack Parlett 2022 op.cit: 221

[18] Ibid: 219

3 thoughts on “‘Queer people have a particular stake in the question of paradise’. Do places have biographies as well as histories, inner lives and the stuff of changes that occur in time tempered by reflection as well as circumstance? The case of Fire Island as see by Jack Parlett in ‘Fire Island: Love, Loss and Liberation in an American Paradise’.”