‘The material was haphazardly arranged, but that only added, I thought, to the authenticity of what she had to say. / Within a few days, however, I had convinced myself that I was the victim of a prank’.[1]This blog contains my personal views of Graeme Macrae Burnet’s (2022 paperback edition. First publ. 2021) Case Study Glasgow, Saraband. REFLECTIONS on BOOKER LONGLIST 2022

This is the second Booker nominated book by Burnet that I have read and enjoyed. Looking back at what I said about his 2016 contender, his debut novel named His Bloody Project, I find my blog mealy-mouthed (as well as ill written) but I have re-issued it so that I don’t pretend that was not the case. See this link if you want to check it out. But what I say about that novel applies to Burnet’s second Booker novel too (the paragraph amended somewhat in the version below and with links to explain some terms and references):

This is from a fictional account that manages the narrative of a fictive event (the ‘bloody project’ as it is named by the real alienist that Burnet introduces into the novel’s mix of history, fable and … something else). This account is to become the fictive basis of other fictions, misrepresenting their original – an original, of course that never itself existed (perhaps) and which is transcribed by a fictive version (GMB) of the real author, Burnet, based on a fictive character with the same name as the author, preceded by a preface full of lies). We are here in the complicated world where truth and fiction coalesce of James Hogg’s Confessions of A Justified Sinner and Thomas Carlyle’s Sartor Resartus – both artists strongly neglected in England but not in Scotland.

Much the same ground as I cover above is covered too by Nina Allen in her splendid 2021 review of the novel in The Guardian. It would be difficult to improve on her general description of this novel and other work by the same author, so I quote her here:

The defining essence of Burnet’s work to date is to be found in this kind of literary gamesmanship, a brand of metatextuality that is as much about exploiting the possibilities of the novel form as it is about blurring the boundaries between appearance and reality. In throwing us into doubt about which – and more crucially whose – story we are supposed to be following, Burnet encourages us to look more closely at the inherent instability of fiction itself. The painstakingly assembled, predominantly mimetic fiction of the 19th century has trained us to trust the author; Burnet has always delighted in undermining such easy assumptions, and in Case Study he ups the stakes still further, providing a veritable layer cake of possible realities to get lost in.[2]

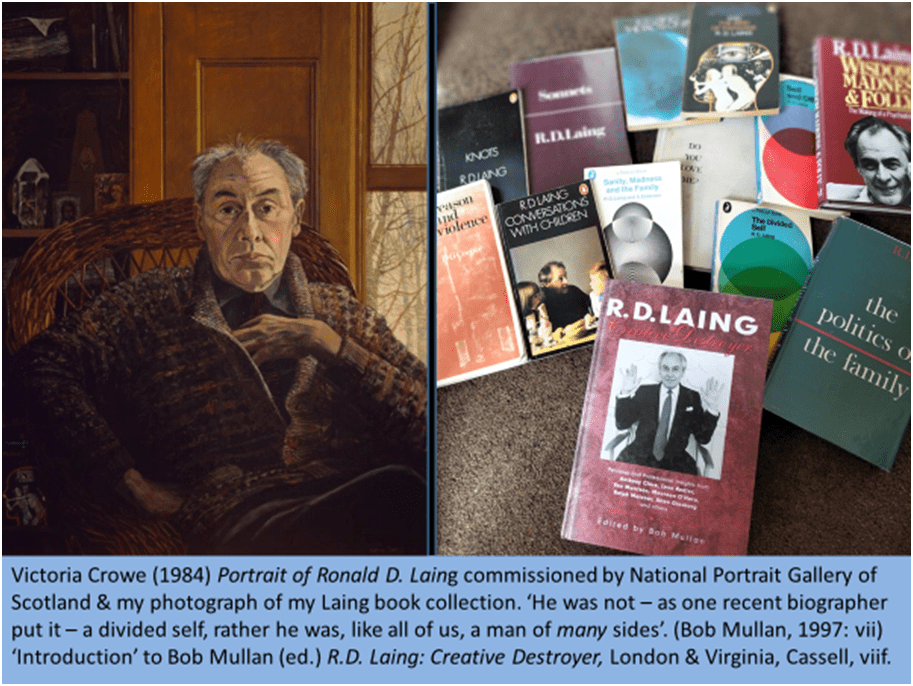

She also notes that, as in the debut novel, the ‘possible realities’ invoked are taken from the history of psychiatry (and pre-psychiatry) and, in this case focusing on the ‘anti-psychiatry’ movement of the 1960s. The focus is in fact mainly upon R.D. Laing, who plays his part in this novel as the mentor (and eventual critic, of the abandoned disciple in Arthur Collins Braithwaite). Throughout, GMB (as in The Bloody Project) renders characters who never existed as if they had. Some reviewers do not even question the reality of Braithwaite’s biography, as told in the book, but the only authority on it you will find on it through internet searches are summaries of the same material as in the novel by Burnet on his own website pages (use link to read it). John Boyne reviewing the novel for The Irish Times makes it crystal clear that Braithwaite’s life, as he tells it, is an elaborate ‘fiction’, calling him a ‘cod-psychiatrist’ in his headline (as far as I read since the review is behind a pay wall) and ‘fictional therapist’. That this fiction names the work of others throughout makes it a work of the same nature as His Bloody Project: Famous ‘real’ names become par of an interwoven tissue of truth and lies, fact and fiction that runs throughout this novel and questions verities which these established authors feel they have made fundamental to our being. This is true of the very real R.D. Laing, a hero of Scottish counterculture.

The presence of R.D. Laing however, in a novel so haunted by issues of discourses of identity is surely not simple. This man, with his supposed antagonism to Braithwaite, also earns Braithwaite’s returned and redoubled hatred for Laing imagined as “sitting on his dunghill Parnassus, his piss lapped up like vintage champagne by sycophantic courtiers”.[3]Laing’s supposed ‘influence’ on Braithwaite is certainly revealed by GMB (the narrative persona of Burnet) as part of his ‘own biographical material’ on the ‘cod-psychiatrist’.[4] Braithwaite we are told ‘read and re-read’ The Divided Self by Laing at the age of 32, finding in it his very own character.

From the very opening pages he recognised himself and his own way of thinking in Laing’s description of the ‘schizoid’ individual as one who ‘does not experience himself as a complete person but rather as “split” in various ways’. Laing goes on to explain how this condition of ‘ontological insecurity’ can lead to the development of a system of false selves: an assemblage of masks or personalities that one presents to the world …[5]

The passage is more ambiguous than it looks, for it is not clear whether Braithwaite sees himself in Laing’s ‘way of thinking’ as an author, though he claims Laing may have plagiarised his doctoral thesis, or in the ‘schizoid’ persons Laing describes. I believe that Laing and Braithwaite are one of the very many doppelgängers (individual components of the same person set in mortal combat) that also appear in Burnet’s earlier fiction and his sources in Scottish literature, especially James Hogg, as previously mentioned, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case Of Dr. Jekyll And Mr. Hyde. If ‘ontological insecurity’ is the cause of split identity, of different forms of being in one source, then this idea fosters not only the double or bipartite personality but also the idea of multiple personalities warring in one apparently unified person and, in extreme cases, as Laing summarised the position stated in his earlier book in Self and Others, the ‘hypothetical end-state of chaotic nonentity, total loss of relatedness with self and others’.[6]

This is very much the range of states of being with which Burnet began his work as a novelist. In this book, even Burnet has a double (GMB) but so do most of the main characters either as a result of their working lives (actors for instance), sex/gender, sexuality or class or other factors in the indication of a person’s ontology – what they are!) as well as their status in mental health case studies. The latter is not excluded and one of Braithwaite’s fictional books deals with Freud and Breuer’s case study of Anna O, in order to show the error of the Freudian assumption of hierarchically organised selves and promote ‘the idea that a person is not a single self, but a bundle of personae, all of which should be valued equally’.[7]

Laing was absorbed into modern Scottish counterculture and counter-narratives well before Burnet’s work. One great twentieth-century esample is Alasdair Gray, who gives plentiful hints of his use of Laing to supplement the platy of his narratives with multiple personality. In 1997 in his edition of a collection of reminiscences on Laing, Bob Mullan says: ‘‘He was not – as one recent biographer put it – a divided self, rather he was, like all of us, a man of many sides’.[8] This use of ordinary descriptive language cannot hide that Mullan believes his witnesses find different versions of R.D. Laing, because these were the reality of his personality. In an essay of 1985 collected in his Of Me and Others, Alasdair Gray recounts how, after being introduced to Laing, the latter ‘embraced me and kissed me long and hard on the lips’, thanking Gray for exposing the link between asthma and masturbation in his novel Lanark which had saved the psychiatrist from doing this himself.[9] Gavin Miller reviewing Gray’s essays and citing other factual errors ( in the Laing essay in particular) hints that Gray might have helped us had he conducted ‘a thorough editorial overhaul and fact-check’. On the contrary however, I would argue that the key theme of that bold little essay (in which Alasdair asserts Laing was probably not drunk when he kissed him though he had thought so earlier) is that Laing is the kind of Scottish hero who, as Laing’s daughters are purported to have said of their ‘Dad’ to Gray was someone who ‘liked to dramatize (sic.) himself’.[10]

The tradition of finding a primary example of the ontologically insecure in Laing himself is then an established one and this is another context that can be remembered when we look to the Scottish novel of metatextuality – it covers a wide range of possibilities of illusion and delusion disguised as the ‘discourse of reason’, forgetting in the process of remembering, decomposition of elements that we thought were being recomposed, and disorder underlying any and every attempt to order one’s materials – in narrative or otherwise. This is why I use the quotation I do in my title, for it starts the story by seeing the process of this book as the re-composition of an ordered and sequential whole from disordered and temporally unstable fragments. Having received the offer of notebooks relating to a case involving experience of Braithwaite’s therapeutic methods and involvement with his patients from Martin Grey, GMB begins to wonder how ‘real’ is the person who makes this offer and the authenticity of their original author. And indeed In the novel’s ‘Postscript’, it transpires that the author of the notebooks may well be a combination of at least three of the novel’s dramatis personae: Martin Grey, Rebecca Smyth and the unnamed narrator, who is the sister of Veronica (called by Braithwaite, Dorothy).[11]

The material was haphazardly arranged, but that only added, I thought, to the authenticity of what she had to say.

Within a few days, however, I had convinced myself that I was the victim of a prank.[12]

This passage plays with the notions of authenticity and faking, self and other and order and disorder. In short it introduces in the very description of its ‘source’ texts (which may or may not exist) the notion of the unreliability of not only their narration but their authority. Nina Allen expresses this compression of all the novel’s issues into the problem that every aspect of the novel – plot, characters and even narration are a ‘prank’ thus:

“Rebecca Smyth” tells us that in her sessions with Braithwaite he constantly questions her account of things, accusing her not only of inventing whole tracts of her past, but presenting him with an identity that is itself a construction. We know that in this at least Braithwaite is right, but with only the fictitious GMB’s word to go on that Braithwaite exists, it would be foolish for us to trust his suggestions or his analysis. The harder we tug on Burnet’s narrative threads, the more Veronica, her sister, and even Braithwaite himself start to look like different aspects of an unsteady unity.[13]

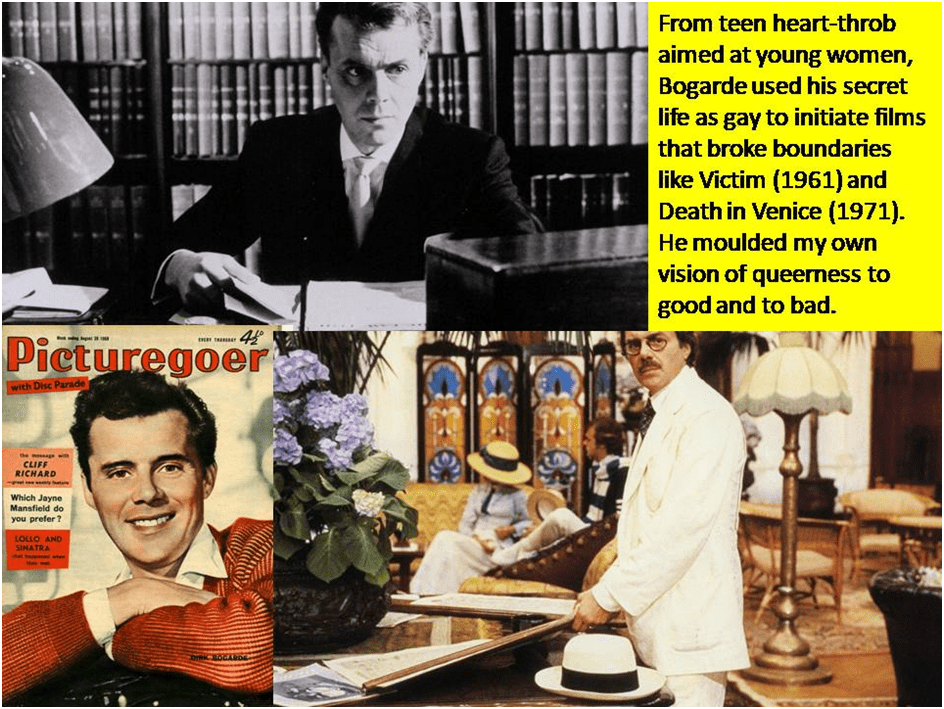

Sometimes there is a reason for adopting a persona or even multiple personae as suggested by Allen. The narrator invents Rebecca ostensibly to find out more about her sister, Dorothy / Veronica, without arousing Braithwaite’s suspicions, although she succeeds in doing precisely the opposite. It is the vocation of the actor and writer and even the reputation seeker like GMB. The classic example in the novel being Dirk Bogarde, in order to understand whom Braithwaite invokes Camus and French existentialism: ‘“It was a relief,” Bogarde told a friend, “to be told it was all right not to constantly ‘be yourself’; that it was fine to be your own doppelgänger”’.[14] Yet Bogarde is attracted to this idea too because of his open-lived queer sexuality. It is Bogarde who leads Braithwaite to argue that ‘all queers are actors’.[15] The fictional book by Braithwaite is based on the notion that completed suicide is so often conflated and confused with the theory that we must ‘escape the tyranny of the fixed, immutable Self’.[16] It is this conflation that troubles us. Is Veronica’s sister actually Veronica herself? The novel deals then with all kinds of reasons why there is a genesis of secrecy at the root of narrative (as Frank Kermode suggests) – but most notably to imply that the interest of narrative is that which, precisely, is hidden in the text, rather than offered up on its surface, sometimes a whole filing cabinet of them.[17]

If narrators usually promise, or at least imply that, they will ‘hold nothing back’ from themselves or their listeners, after saying that very thing, the narrator of the text of the ‘notebooks’ pretending to be the novel’s source presents ar text to posterity that is mutilated at this very point. The next page is blank with the legend:

[THE FOLLOWING TWO PAGES OF THE NOTEBOOK HAVE BEEN TORN OUT][18]

And secrecy and reserve produce not only confusion and mystery but also a way of experiencing some degree of freedom whilst still appearing to be constrained. This is how Rebecca masturbates in the novel for instance: ‘Under the guise of sleepily shifting my position, … I began to amuse myself with the tiniest movements of my middle finger’.[19] The game the same person – although slipping between doubled personae is that between pleasure and restriction (and constriction). Braithwaite catches the narrator of the notebooks out by her apparent oxymoron related to this: “Why do you think you enjoy being shackled?”[20] It leads her to reflection on the use of ‘reins’ on errant children and her ambivalence around schoolgirl ‘excitable talk about The Penis, this chiefly concerning its dimensions’.[21]

No-one in this novel can ever trust that someone’s identity is what they say it is – and not just in therapeutic interview – or that they exist at all. Note the enigmatic Miss Kepler: ‘When I looked back along the street, Miss Kepler had already disappeared, and I had the feeling that she had never been there at all’.[22] Of course, one can point to collateral evidence for someone’s existence, but even in terms of the notebooks as GMB says, the evidence is sometimes itself ambivalent.[23] And perhaps most important, fiction writers perhaps live off such ambiguities – on the cusp of fact and fiction, including stories about Bogarde and Laing, if the recounted events will ‘form the basis of an interesting book’.[24] Some of the interest is psychodynamic – the book plays, for instance with the forbidden mysteries of incestuous attraction as the narrator contemplates his father’s housekeeper as attending to ‘those needs from which a daughter is debarred’.[25] This is creepy indeed.

Of course the shortlist is drawn up and this novel has not made it. This is not a reflection on its quality but it may be on the fact that the novel is more cleverly interesting than a portal to necessary enlightenment; because the latter has been offered many times before – by Alasdair Gray for instance, but even in the classic Scottish tradition of the nineteenth century. To understand these go back to that splendid account made in 1985 by Karl Miller Doubles: Studies in Literary History, wherein Miller says (and I almost remember this from his UCL seminars on Stevenson and Hogg): ‘The double stands at the start of that cultivation of uncertainty by which the literature of the modern world has come to be distinguished, and has yet to be expelled from it’.[26]

Read it though. It is enjoyable, funny and knowledgeable (if tricksy).

All the best

Steve

[1]Graeme Macrae Burnet (2022: 2) Case Study Glasgow, Saraband

[2]Nina Allan (2021) ‘Case Study by Graeme Macrae Burnet review – unstable identities’ in The Guardian online [Thu 14 Oct 2021 07.30 BST] Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2021/oct/14/case-study-by-graeme-macrae-burnet-review-unstable-identities

[3] Ibid: 264. The imagined citation of Braithwaite reminds me of the imagery of Alexander’ Pope’s The Dunciad but I find no reference and I read it too long ago to find one myself..

[4] Ibid: 4

[5] Ibid: 172f.

[6] R.D. Laing ([1971: 51] The Penguin edition of the 1969 second edition of the original 1961 first edition) Self and Others Harmondsworth, Penguin Books Ltd.

[7] Burnet op.cit: 119.

[8]Bob Mullan (1997: vii)‘Introduction’ to Bob Mullan (ed.) R.D. Laing: Creative Destroyer, London & Virginia, Cassell, viif.

[9] Alasdair Gray (2014: 206) Of Me and Others Glasgow, Cargo Publishing

[10] Ibid: 207

[11]Graeme Macrae Burnet op.cit: 276

[12]ibid: 2

[13] Nina Allen op.cit.

[14] Graeme Macrae Burnet op.cit: 183

[15] Ibid: 184

[16] Ibid: 184

[17] Ibid: 201

[18] Ibid: 61f.

[19] Ibid: 156

[20] Ibid: 83

[21] Ibid: 89

[22] Ibid: 167

[23] Ibid; 3

[24] Ibid: 4

[25] Ibid: 135

[26] Karl Miller (1985: viii) Doubles: Studies in Literary History Oxford, Oxford University Press.

4 thoughts on “‘The material was haphazardly arranged, but that only added, I thought, to the authenticity of what she had to say. / Within a few days, however, I had convinced myself that I was the victim of a prank’. This blog contains my personal views of Graeme Macrae Burnet’s (2022 paperback edition. First publ. 2021) ‘Case Study’ Glasgow, Saraband. REFLECTIONS on BOOKER LONGLIST 2022”