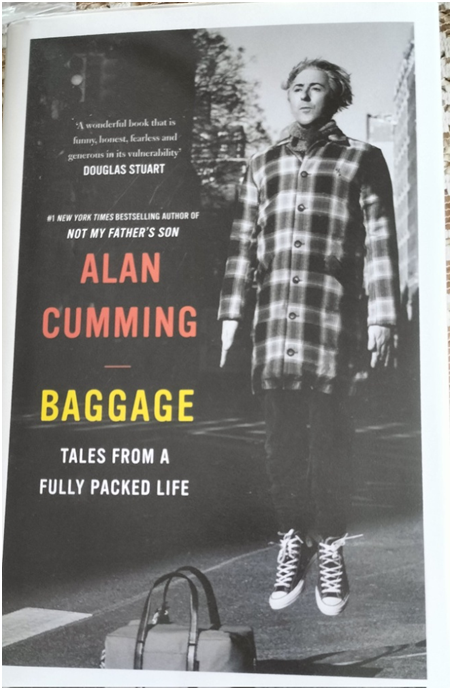

‘I did more research on Alan Cumming for the writing of this book than I have ever done for any character I have ever portrayed’.[1] This blog focuses implicitly on the fascination readers and festival goers seem to have for observing celebrity (or ‘seeing stars’) and reading their ‘stories’. This blog looks at why I booked to see Alan Cumming at the 2022 Edinburgh Book Festival on Sunday 21st August. It uses, as the evidence for exploring its expectations of the event, my reading of a recent memoir (his second) by Alan Cumming [2021] Baggage: Tales From A Packed Life Edinburgh, Canongate Books Limited (pictured). The blog is updated after seeing the event.

I have seen Alan Cumming in live theatre only once. It was when in 2012 he performed in Glasgow (at the Tramway Theatre I think) in a production of Macbeth for the National Theatre of Scotland. In this he enacted the always present and over-arching role in the play of a man incarcerated in a therapeutic-cum-custodial mental hospital who becomes of all the Shakespearean roles in Macbeth and ‘lives’ its text. This man, damaged and bleeding, is the focus of the warring and sometimes duplicitous entities that are the dramatis personae of the ‘Scottish play’. However, the story of Cumming’s present memoir does not reach as far as 2012 and the only significant mention of Macbeth otherwise is of a 1985 production in the Glasgow Tron Theatre, which like other early roles (many celebrated at the time), Cumming dismisses as ones in which he was not so much ‘bad’ but ‘could easily have been better’ (and which ‘it irks (him) to this day that (he) wasn’t’). This last cited sentence comes from a chapter (entitled ‘Authenticity’) and indicates a turning point in the actor’s career of which he says that he had not yet ‘realised what acting was about’. [2]

Cummings in the 2012 Macbeth then enacts a man whose identity is not as much that of a man but a damaged transmitter, which tries, but fails, to contain (in the sense of keep inside him) the character and story of Macbeth. The play becomes a series of interacting and cross-cutting authentic feelings which have exhausted and torn apart the embodied brain, voice and actions they needed to bring them into being. This man’s posture and look (as of a man from whom life is draining) the National Theatre of Scotland and Cumming can be seen in the amazing publicity shots such as those below.

In the chapter ‘Authenticity’, Cumming also says, almost as if in preparation for a man who is a play rather than a character, that ‘acting was all about’ listening to lines written for that purpose, getting ‘lost in the scene, and simply [letting] myself feel what my character was feeling’. Although in the text the elaboration of this principle of ‘authenticity’ can seem far from what one expects from even a thin account of how an actor prepares, its application in the 2012 Macbeth allows us to see that his account of his learning presages an actor giving up his embodied identity to things that rip their being from within him using his voice, body and visceral emotion as a vehicle only, leaving something literally worn, damaged and cut up by them behind: ‘I was authentic. I lost my self-consciousness. I stopped trying to put layers on top and let a bit of myself come through’.

The couple of sentences last cited in effect means that the actor allows his body to become a transmitter of feelings by action, voice and ‘look’, as if it is ‘pretending to be someone (or something) and meaning it’. Such pretence is not without cost for to ‘mean’ to be realised necessitates losing protective layers of the habitual ‘self’; stripping them off, as Lear does his sumptuous ‘lendings’ in Act 3 Scene 4 of his play chastened by the nakedness of mad Poor Tom, and offering his body as the means to facilitate his possession, quite literally, by a whole play of different entities. Those entities (the characters from the text of Macbeth) include those living, those dead, those which struggle to come into being, and, of course, elements of the supernatural. [3] The odd thing however is that this possession of the self is also talked about by Cumming as a truer underlying self emerging out of the ‘disguises’ and shallow enactments that make up the life of any actor including the ‘celebrity star’: ‘It’s not about sounding or looking like yourself. It’s about letting an audience see who you are no matter what disguise you are wearing’.[4]

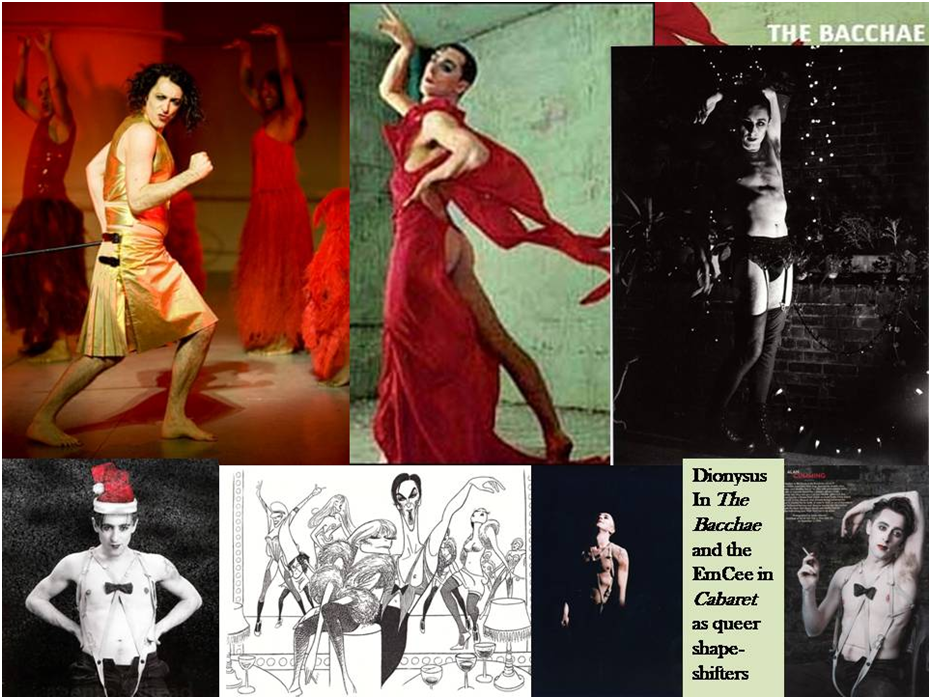

Reading the words Cumming writes in his memoir at this point gives little sense of the process of daemonic possession and creation that is about giving up, or freely varying, the norms that usually govern the appearance or ‘sound’ one presents to the world. However, that (almost supernatural-seeming) process is implicit in his famous roles of queer shape-shifting and uncontrolled flow of multiple forms of experiment with the outer ‘person’ and ‘self’: such as the oft-cited Dionysus (a production I fought hard but failed to get tickets for) in The Bacchae in the 2007 Edinburgh Festival or the equally shape-shifting ‘character’, if that is the right word, of the constantly resurrected Cumming version of the EmCee (MC) in Cabaret.

What all this suggests is that the deeper self that the ‘authentic’ actor wants to bring to the surface in the different roles they inhabit also shifts between those roles. It may in the process differ in shape but not in its essence, for it is something plastic and free of norms of the social regulation and control we otherwise live by as our scripts and schemas of everyday life. This process Cumming elides with his own escape from a heterosexual marriage that he took on as a function of social expectations and other regulatory controls on his experiments in life. And that process occurs in both in enacting the roles he takes on in the theatre or film AND in the flow of self between the people and things he gifts with his body sexually including objects worn, carried or made part of that body. Features of the psychosocial setting of the period of history described here feeds into the changes Cumming describes himself as experiencing. These range between profound shifts in self-conception and the most trivial forms of letting-go in play in both art and life that characterised aspects of the lives of many people in the UK in the 1990s. Shape-shifting happens in art in the loosening of the boundaries between art genres and that supposed by elite cultures to make the supposed difference between high and low culture.

From the beginning of my career I have careened from genre to genre, up and down the ladder of cultural taste. … More recently I have been as enthused at writing, directing, and acting in a musical condom commercial (co-starring Ricki Lake) as a recording a CD of Shakespeare speeches, having Chekhov revealed to me by a Russian director, duetting with a jazz band, designing shoes or wallpaper or T-shirts, or woring with a new writer on a play that pushes the envelope on interracial, intergenerational queer relationships and involves much nudity and swimming.[5]

This shape-shifting experimentation in art, taste, and in the deeper exploration of pleasure (and let it be noted the pain involved in some change (or dissonance in) of psychosocial identities) he calls his ‘Dionysian season of discovery’. Naming it thus makes his embodiment of Dionysius in the Edinburgh The Bacchae the more interesting. It aligns his acceptance of that role (though this an uncomfortable fact for some rigid over-serious art-obsessed lefty types like myself) with playing the part of a queer director in a film about the music of the ‘Spice Girls’ and their ethos of girl power – which is, he says, ‘essentially equality and empowerment combined with unabashed and jubilant embrace of fun’. It comes as no surprise then that Cumming also says, and not just because he dislikes ‘intellectual snobbery’, that the favourite of his film appearances is that in Spice World. His part in that experience for him almost defines for him that experimenting shapeshifter called ‘self’: ‘the fun you’ve had, the people you’ve met, the friendships you’ll maintain, the places you’ve gone, the things you’ve learned and experienced, the life you’ve tasted’. [6] In the collage below that definition seems encapsulated in Cumming’s torso marked – as if by the sacrificing cuts of life – by the signatures of the Spice Girls.

The norms challenged by Cumming are wide: they represent taking on the perspective of the relatively less powerful against more powerful; such as the championing of Scottish independence of England and the pretence of a United Kingdom, the diversity of the marginalised groups, including minorities in the population, in Scotland against the hegemony of the notion of the Western Central Lowlands Scotsman (represented by ‘for the most part a buttoned-up bureaucrat in black suit and a tie’ Pentheus played by Tony Curran in The National Theatre of Scotland’s The Bacchae) and the notion of the transgressive queer in a wide range of contexts. In The National Theatre of Scotland’s Macbeth, the division and self-alienation of the focal role playing all the Shakespearean characters is in a sense also Scotland threatened by treacherous self-divisions (including a pretend underdog defence of oppressive Unionism) for instance. The ‘madness’ of the person played by Cumming is a representation of the repressed and self-alienated other of Scotland as a whole. It is a source of ‘deep’ delight

He also, as we have seen, challenges ‘highly elitist’ notions of art as an ideology with a love for the popular and populist. An early symbol of this is his story of his original adoption of the form of language used once in drama schools(and more widely) of Received Pronunciation (or RP). This phenomenon in language use was used as a weapon once to reject or refuse other forms of English speaking than those regulated by it . Challenging it was a route back for Cumming to a ‘Scottish voice, and by extension, a major aspect of my authentic self’. It is also, of course, a recognition of the causes of relative ‘undereducation’ in an aetiology of structural deprivations related to class or regional origin.

More well known is Cummings frequent public challenges to cultural mechanisms which create a class of persons susceptible to being popularly reviled. One such individual case is that involved in his friendship with Monica Lewinsky. Recognising her undergoing ‘humiliation and cultural abandonment’, he praises both her analysis and brave resistance to processes of ‘shaming’ in social media.[7] This is one example amongst many of a practice defined by norms he names ‘slut shaming’, which can be applied he was to find against all sex/gender categories. The practice resembles the oppression of ‘othered’ sexualities too by versions of Puritanism, which he sees at base as setting itself against demonstrations of ‘sex positivity’, even when practiced by those who want simultaneously to condemn it: ‘Letting go, which to me is a positive and necessary part of the human experience, is seen as a lack of restraint, of decorum, of self-respect – and instead of giving oneself up to an experience, or a feeling, or a desire, it is instead characterised as giving in’.[8]

And talking about othered experiences must also include the experience of what is labelled ‘insanity’ or drugs used to control stress, anxiety and release the ‘me that was hedonistic and sexual and free’.[9] People who ‘prepare to be, or simply just’ are ‘vulnerable and open’ about passion, pain, hurt and oppression (and ‘ecstasy’ in both sense of the word – as feeling or drug) are indeed, for Cumming, the very model of ‘my kind of star’, whether they be waiting staff, bartenders, drivers or farmer. His favourite is : ‘a friend who works in LGBTQ+ rights’ being ‘one of the brightest in the firmament’.[10]

At this point it seems appropriate to consider the LGBTQ+ campaigner and life-model that was Cumming himself. Of course, treated as a ‘coming out’ narrative, this memoir must disappoint because there is no marked trajectory in it for that process other than in scattered pieces. I cannot know, of course because I haven’t read it, whether this was in his first memoir, Not My Father’s Son: A Family Memoir (although no hint that it is included is suggested in the publicity descriptions of the book).

In this second memoir, Cumming starts off apparently publicly committed to heteronormativity, if of a liberal kind, leading up to his marriage and its breakdown. There are increasing references and asides however to Cumming’s mature identity as a ‘queer man’ as the book progresses, taunting the reader’s public knowledge of the fact of such self identification by reported jokes, or jokes directly to the reader. The discussion of sex is never anything but potentially bisexual, at least, in its application, such as the remarks about the mechanics of non-reproductive sexual activity being falsely and lazily called in American society ‘fooling around’.[11] This discussion constantly segues between accounts of ever greater experimentation in Cumming’s OWN sexual life and that of differing characters played in the public theatre. For instance, in discussing the elaboration of the ‘openness and shamelessness of the sexuality’ of the EmCee in Cabaret, whose ardor extends even to animals (a meaning not usually applied to the term pansexuality), in his version of the role on Broadway, he says:

… it wasn’t just the production that had expanded. In the previous four years I had become more comfortable with myself and confident in my abilities in the role and so willing to push the envelope of my character’s sexual manifestations even further than I had in London (I still joke that I am proud to have administered Broadway’s first fist fuck!).[12]

For actors learn to expand the possible business to which they apply their minds and bodies, not only in their public art and celebrity persona but also in what is sometimes laughingly, in these non-binary days, called their ‘private life’. Cummings defends open talk about sex and abandoning euphemistic phraseology such as ‘making love’ and ‘fooling around’.[13] He describes his own sexual and romantic practice as an amalgam labelled ‘all in’.[14] Cabaret and The Bacchae made him in America, he says, ‘a full-blown sex symbol. Geeky, arty, skinny, European, mischievous, slightly dangerous sex symbol, but sex symbol nevertheless’.[15] This makes him able to compete with such symbols surviving the past, such as Lauren Bacall, Liza Minnelli, Faye Dunaway, and for his famed European home of gay sexual encounter, Gore Vidal and some still current.

I started this blog citing a sentence from the chapter entitled ‘Finally’ where it is clear that Cumming’s belief in performance art extends to the need to authenticate, perhaps the word is used in Rogerian terms even the role we call our own deep self. The reason for this is obvious from the above because the self is something ever constructed and emergent that can wither and die, even before the death of the body, or grow and develop out of interactions with the physical, intellectual, emotional (and indeed spiritual) environment. And hence that self can be researched, and its triggers understood and tendencies outlined, that are not always different from those relating to multiple other persons, especially when the lives of these others become unreasonably contested by people in political and cultural institutions regulated by norms alone. Cumming points to where such regulation once appeared in forces he thought to be in the LGBTQ+ corner such as the Blair New Labour Government who feared ‘upsetting middle England’ in its legislation on gay and lesbian partnerships and thus modified it to a secondary status.[16] Cumming ends by highlighting the surprises changes in the world and attitude that sometimes light up in the self in its adaptation: of his current marriage he says ‘’ … we were happy, secure, calm. I didn’t need ceremony to quantify my love for this man. And then suddenly I did’.[17]

As I examine my reading of this memoir I try to hone my expectations of seeing Cummings in the flesh on the 21st August this year. I look forward to it, for the person embodied in the here and now can only be more of a revelation of the notion of identity emergent through interaction, even staged interactions such as occur in the Edinburgh Book Festival. Questions from the audience open up a person sometimes – although sometimes not because either there is nothing to be opened up or the person is too guarded in body and mind to do so. But this book is a celebration of the ‘open and vulnerable’. If an audience and its members embrace this principle Q & A sessions can be miraculous. On the other hand they can be killed by over-effusive control of the Stuart Kelly kind or ghosted by an interviewer’s nervousness, as I remember one being with that ‘open and vulnerable’ man, Colm Tόibín. I keep an open mind and look forward to seeing this joyous person; ‘(g)eeky, arty, skinny, European, mischievous, slightly dangerous’ as he may be.

UPDATE AFTER SEEING THE EVENT:

This was a joyous occasion. Seeing the person illustrated how authenticity is something different from mere consistency, for consistency is a kind of rigidity. Authenticity includes play with the incidentals and superficies of shape to see what is real in the negotiations with the world we take on – which explore not only excitement but deep darkness. When he played Macbeth in 2012 he thought he might die of the experience he said in answer to my question from the floor. He is honest and wonderful. This was a moving communal experience from which the audience left uplifted.

All the best

Steve

[1] Alan Cumming [2021: 265] Baggage: Tales From A Packed Life Edinburgh, Canongate Books Limited

[2] Ibid: 150f.

[3] Ibid: 151

[4] Ibid: 161

[5] Ibid: 107

[6] Ibid: 108f.

[7] Ibid: 176

[8] Ibid: 170

[9] Ibid: 168f.

[10] Ibid: 151

[11] Ibid: 171

[12] Ibid: 172

[13] Ibid: 190ff.

[14] Ibid: 196

[15] Ibid: 174

[16] Ibid: 259

[17] Ibid: 262

One thought on “‘I did more research on Alan Cumming for the writing of this book than I have ever done for any character I have ever portrayed’. This blog looks at why I booked to see Alan Cumming at the 2022 Edinburgh Book Festival on Sunday 21st August. It uses … my reading of a recent memoir (his second) by Alan Cumming [2021] ‘Baggage: Tales From A Packed Life’ (pictured). The blog is updated after seeing the event.”