‘Painting, as Patrick Heron said, is a materialist art, about the material world. The novel, however it aspires to the specificity of Zola’s naturalism, works inside the head’. [1] This blog reflects on Honoré de Balzac’s ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’, the limitations of theory of how art works as a path to producing or appreciating it, and the assertive brilliance of A.S. Byatt (2001) ‘Portraits in Fiction’ London, Chatto & Windus.

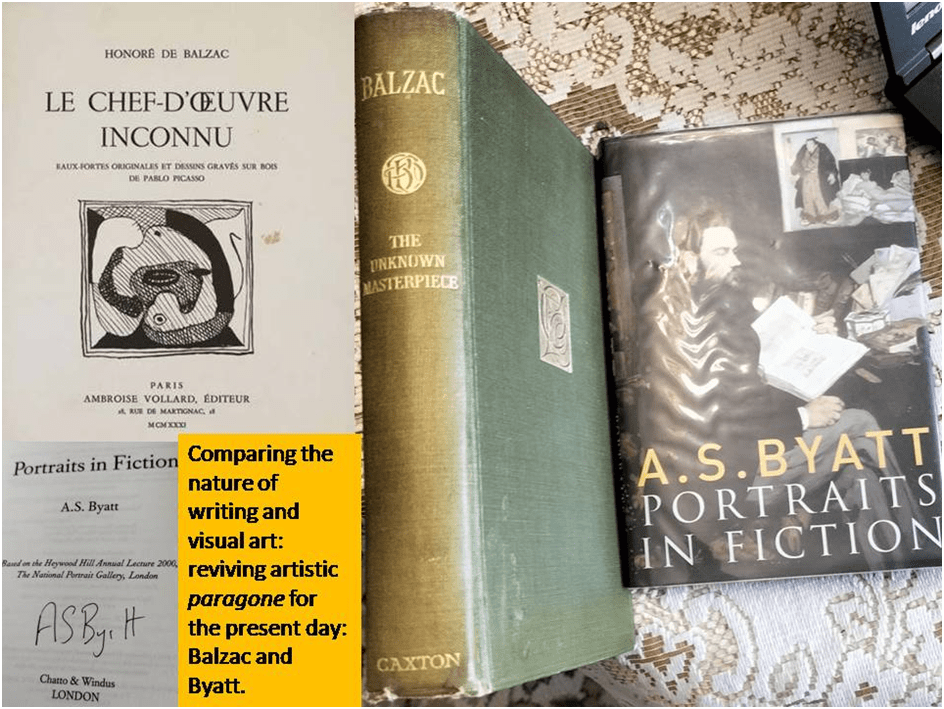

A.S. Byatt taught literature at University College London when I was a student there and being taught the dynamics of discourse about literature by her was a source of great influence on many people there including me, even though it must have seemed to her the least of her lifetime achievements. Known to us as Mrs Duffy (her married name to her second husband, Peter) we were naive and whispered in the corridors with awe but as yet incomprehension of the gulfs within the true relational dynamics we traversed in that gossip that she was the sister of Margaret Drabble (then somewhat of a heroic figure of the novel that deals with social ‘issues’) whilst she was largely unknown to us as a novelist. Later seeing Byatt answering questions about her sister at literary festivals, made me shudder at my insensitivity to the reality of intra-family dynamic at that time. Byatt at these festivals often stated, some people believe coldly: ‘I do not discuss my sister’s work’.

Yet each of us knew, or suspected (if they weren’t prepared to read it for themselves) on the basis of the gossip of those who felt they did, that The Game, Byatt’s second novel was supposedly a semi-autobiographical story about sisters who both aspire to great writing (based on identification with stories and myths about the two best known Bronte sisters, Charlotte and Emily). The novel is about two literary sisters and written in revenge, some said, for Drabble’s inclusion in her novels of figurers based on her sister, Antonia Susan Drabble (she became known as Byatt by her first husband, Ian Byatt) that were wittily transformed in her second novel, The Game. Therein Julia’s shallowly self-justifies basing a novel on a ‘lady don’ like her sister, Cassandra (whose name alone spells out the doom implied in the novel), a ‘weird heroine’ who ‘sees everything with a steady, lunatic, clarity’.[2]

Reductively speaking, in The Game Julia is a popular, but self-consciously ambitious novelist of social issues who aims for status in the literary world. Cassandra is a donnish depressive intellectual shrouded by deep psychological mysteries involved in the making of stories from language which effectively repress her writing advent. Cassandra then is superficially like Byatt in being absorbed by the mediation of communion with a material world (that she too knows to be in need of change and lacking in social justice) than by those material realities themselves and interventions in them. That mediation is bound up in the complexity and dangers of story-telling and the inner truths about how the world can be made knowable by the human mind at all. For if knowable, it is in fragmentary and contradictory ways because both written language and the very processes of complex story-telling reveal and conceal (sometimes the latter by defensive necessity) the nature of relationship of the mind that attempts to know the material world and the material world itself

There are odd truths in the stereotypes which play against each other in the dynamics between these sisters. The chief of these is that attempting to see the world steadily and be honest about how it appears to that refined observing capacity inevitably seems ‘lunatic’ to those who prefer not to see beyond surfaces at all. People like Julia. Indeed Byatt demands, I believe, that we grow into intellectual maturity if we not only wish to know the world but also know the art of knowing deeply the various media by which that knowing is represented.

For instance, In my title to this blog I cite Byatt in Portraits in Fiction talking about Patrick Heron the Cornish painter. Therein she says: ‘Painting, as Patrick Heron said, is a materialist art, about the material world’.This elegant simplification however ought to be seen in the context of the case she made for her admiration of him in a 2015 review in the Guardian of a retrospective exhibition of his painting. The Guardian piece is a more searching articulation of what underlies that stark statement about Heron I cited. It is a piece about concern with the potential strengths and limitations of the means of representation in visual art (even when we may not exactly see them as about representation or mimesis as Heron once did not) of a material world that is both concealed and revealed by them.

He was wise about the relationship between abstract forms and representation in all kinds of painting. In his essay on “Pierre Bonnard and Abstraction” he wrote a wonderful bravura passage on the varying underlying abstract shapes of every great painter. Velázquez painted eggs and fish, Picasso flat triangles, El Greco solid diamonds, Rubens “endless spheres” and Bonnard “a large-scale fishnet” pulling the surface of the canvas into loosely connected squares and lozenges. I think that one of Heron’s own underlying shapes is a kind of attempt to square the circle – a hook that has a square angle, a triangular point and a curved hole inside the angle. There was a time when Heron was belligerently abstract, needing to paint purely abstract forms. He was, he said, startled when Herbert Read found a source for this resolute abstraction in Heron’s own surroundings – in the forms of the lichens on the stones in his Cornwall garden. He came to see that many of his hooks and piers resembled the Cornish coastline and harbours. He painted the abstract forms underlying his world.[3]

Implicitly here Byatt’s writing praises but also demonstrates how writing takes precedence over visual representations because words and linguistic structures have a more direct line to the internal thinking and feeling mechanisms of individual minds. For only the latter see and ‘read’ the world we think we know – whether they read well or badly. That there are ways of seeing and reading that are relatively closer or distant to both the material world and its representations Byatt has no doubt of course, just as she is convinced that individual minds differ in how well they use these ways of seeing and reading as either writers or readers. It is a thing she illustrated from her first novel onwards, where Anna wonders what the consequences would be of reading her father, Henry’s novel, more closely: ‘She had in fact read Henry’s novels, each of them, once and no more, as quickly as possible, partly out of a feeling … that in some way to study them too closely would be to submerge’.[4] Some readers resist ‘submersion’ in what they read or see. That is to be expected.

Meanwhile we have to note that Byatt’s admiration of Heron was not because he simplified the processes involved in producing art or representing the material world in his art but because he sought to see beneath the material means he must, by necessity, use to represent both persons and the ideas which these persons represented in the world. She chose him as the painter of her own portrait for the National Portrait Gallery, the role of which is to represent the ideas that make a person significant to a nation, precisely because his use of ‘resolute abstraction’ as a medium of expressive design was a way of using the material in art to design ‘abstract forms underlying the materials world’. For abstractions such as the concept of the ‘writer ‘are what interested her in being portrayed to the public gaze of a nation. What is achieved in her portrait is something I would argue that is very much that. The writer appears through patterns created from dense material layers of coloured paints that neither attempts nor achieves specificity of a designed look or mere appearance. The figure in the painting is not explicitly gendered and dense colour patches obliterate, as well sometimes make more apparent the lines that draw the margins as well as indicate the three-dimensional features of the body. Coincidentally the play between lines and colour interactions are a theme in Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece too (which we consider later), wherein the mad reclusive and imaginary artist Frenhofer says words that describe this portrait’s method:

I have not, like a multitude of ignorant fools who imagine they draw correctly, because they make a sharp, smooth stroke, marked the outlines of my figure with absolute exactness, and brought out in relief every trifling anatomical detail, for the human body is not bounded by lines. … there are no lines in nature, where everything is rounded…[5]

In the case of the Heron portrait of Byatt, the principle of its design is, I’d argue, a rounded negotiation between internal and external depiction; signalling configurations of the conceptual, emotional and the visceral in the person. Mind (as a knowing and feeling mechanism) and the ‘too solid flesh’ are both nevertheless indicated by skins of physical masses of paint. It is worth keeping that portrait in mind for the discussion which follows:

In Portraits in Fiction Byatt concludes a survey of writing about painting in written stories by referring to her own later Possession of 1990.Looking at portraits of the poet, Ash (invented by Byatt but based on numerous real models including Robert Browning) Roland Mitchell in Possession]:

thinks also about the poet’s words, which in the case of real writers are their real selves, as much as, or more than their skin and eyes. He thinks about how the images we see, the painters who made them, are part also of what we see and read. …

“… You could read it either way; as though you were looking into a hollow mould, as though the planes of the cheeks were sculpted and looking out. You were inside – behind those closed eyes like an actor, masked: you were outside, looking at closure, if not finality. …”[6]

For me, that says something too about the Heron portrait of Byatt, with its ungendered and unselved materiality, offering its vaguely indicated facial features as channels to recreated senses that writing and reading involve as well as access to underlying patterns and forms that interpret the world in that triune relationship of artist to world and to readers/seers. These are eyes and ears a viewer can inhabit as Roland inhabits Ash through his portrait.

Yet Byatt is unremitting in Portraits in Fiction (and we will pursue this later in relation to her fine reading of Balzac) in her insistence on a possible superiority of writing in any paragone type competition between writing and painting. The same one-sidedness is sometimes found, but not always, in the Renaissance and Baroque paragone debates between sculpture and painting, as I have attempted to explore, in my own sweet amateur way, in relation to Spanish art and the problems of categorising the polychrome sculpture (use link for my blog on this). Sometimes Byatt’s method, if ill-read by its reader, can seem crude in its claim for the triumph of writing over visual art, yet we can already see from the foregoing that her appreciation of the comparison of painting and writing is far from crude. But a doubt is raised, and I believe (but can’t prove) is playfully intended, about the subtlety of the comparison from page 1 of this essay on art in fiction: ‘A painting exists outside time and records the time of its making. It is in an important sense arrested and superficial – the word is not used in a derogatory way’ (my italics).[7] To describe painting as ‘arrested and superficial’ takes a risk in terms of how one’s argument may be understood that isn’t quite mitigated by Byatt writing that ‘the word is not used in a derogatory way’. For which word did she mean here since both are potentially derogatory in a comparative evaluation of two phenomena?

We think of being ‘arrested’ as a limitation when applied to the success of an intended dynamism of motion or operation, especially when applied to notions of human development. To be ‘superficial’ is to lack any penetrative understanding in our thinking. Yet though neither word is used in that way: it describes the fact that paintings do not exist in as consequential a time frame as the ‘end-to-end reading of a book’. There components of interactions of colour and design have a relative simultaneity (although the word relative is important here) compared to written books. Similarly paint (however layered) is applied initially to a flat surface and once applied stay on that surface unchangeably, while writers and writing ‘rely on the endlessly varying visual images of individual readers and on the constructive visualising those readers do’. Those shifts between and within individual readers means that words cannot exist alone on the flat surface of the book. But when put together the two words ‘superficial’ and ‘arrested’ associate with each other, I would suggest in most minds, to revive their derogatory associations. It leaves most I would guess with the implication that painting is a less valuable achievement than writing, even when both are performed well.

I think this is worth dwelling on even though we know for certain that Byatt does not believe any such simple formulation of the paragone in this essay. For great artists struggle precisely with the fear that their art will arrest the development of a viewer’s interest beyond the superficies of what a painting exhibits outwardly, and this is why she chose Heron as a singularly great contemporary artist. There is nothing merely arrested or superficial in Heron’s portrait of her. She sees it as an invitation to imagine the writer in the process and with the felt capability, felt in the viewer, that this figure is about to write and will do so in living time. Thus far from arresting a reader’s attention by a completed picture of a woman stilled in time, the figure here (androgynous in some ways as I have suggested) has an unfulfilled nature in relation to figural outline and features. It seems to emit motion in the e-motional tone of its stark and conflictual opposition of the colours blue and red that only partially form blocks of similar and inverted shape, for the blue is invasive of the red. A possible colour association here is that in Catholic iconography of the Celestial Mary (associated of course with rich BLUE colours, in her role in Revelations as the woman clothed in the sun). For Catholic readings of Revelations stress that the Virgin fights the Satan in the form of the great RED dragon.[8] The yellow in the portrait fills a central aperture between the conflictual interaction of red and blue blocks which almost captures the sense of sun represented through a window between differently coloured walls. This complements the suggestion of mythic icon of the woman clothed in the sun, who wears a crown of stars for that yellow almost forms a corona over Byatt’s head. I feel confident in this association because Byatt makes a similar one in unearthing the woman clothed in the sun in Zola’s picturing of the artist’s vision in L’Oeuvre, a novel thought to represent his childhood friend, Cezanne.[9]

Now, although Byatt uses this icon in her novels, particularly in The Virgin in the Garden which takes that image in part from Spenser’s Faerie Queene Book 1, I would not argue that either she or Heron wished to infer here a religio-political allegory as in that early book of Byatt’s The Frederica Quartet (and in Spenser).[10] It is rather that Heron structures emotion in the hint of that figure for figuring a woman clothed in the sun allows the writer to represent a heroic identification with a battle we all fight to be complete, when we feel our way into a positive stroke or two as artists and readers against red dragon self-centred materialism. Whether these formal associations are taken or not, it is clear that the sun colours here warm the blue such that it cannot be arrested in one figure, the drawing of whose internal features lines are overlaid, but as often blotted out by the painted design. We are not here arrested in time and neither is Byatt for our attention is never with the superficial characteristics of the portrait, such as face and figure but the suggestion of larger internal meaning through formal visual means.

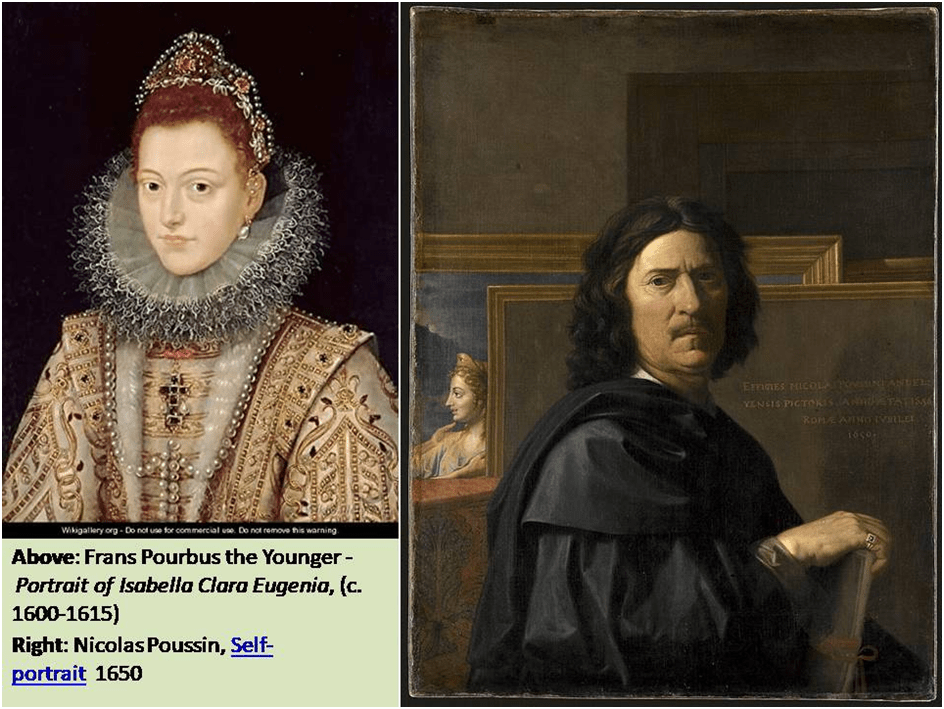

I think we are in a position by now to see why the discussion of Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece takes the central position it does in Byatt’s book, dealt with in over eleven pages of typeface in this short book, which nestle within them the first set of colour plates. And its position is important in the argument too because it allows us to see why Cezanne and Picasso, whose interest in the Balzac story is a launching board for Byatt’s interest in these innovative artists. Cezanne and Picasso are precisely the reason that painting does not in the twentieth century and beyond become ‘arrested and superficial’ (in a derogatory or any other sense) but takes on some of the issues which in some respects make writing developmentally richer and deeper than say art of ambivalent quality, even when done by artists whose names are great in the ears of the academies of national art, such as Nicholas Poussin, a representation of whom appears in Balzac’s The Unknown Masterpiece. In that work appears a representation of another figure from art history, if much less well-known than Poussin, Frans Pourbus the Younger. The mix in Balzac’s story between a person who became a known master of the Classical Baroque (if that is not a contradiction in terms – which I think not) and a much lesser figure is important because Balzac’s story is set in Poussin’s youth, when he sought models for his artistic practice amongst more acknowledged names.

The true Master in the story however is a fictional character, a Master Artist invented by Balzac called Frenhofer, whom Byatt calls a ‘daemonic creation’. In Byatt’s excellent reading Frenhofer is not a hero of his tale, his masterpiece only so because he falsely names it thus. It is not because the two ‘real’ painters do not ‘know how to look at’ this painting that makes it seem to them a disintegrating disaster but because Frenhofer has taken ‘one step too far in the seriously obsessive process of constructing’ the image of his nude female based on the myth of Mary of Egypt. She believes that such a conclusion is inevitable on ‘close reading’ of the tale. [11]

Yet Byatt also notes that there was a reason why Frenhofer became a heroic icon of the artist and his ideal relation to the model as the material of his art to Cezanne and Picasso. She tells that Cezanne indicated by gesture to Emile Bernard rather than words that he considered he was ‘the fictional character himself’.[12] Byatt has already given one reason why Cezanne, and after him Picasso, could see an analogy between themselves and this failed genius who burned all his works on his death or suicide at the end of that story. For, she says: ‘Balzac understood, and could represent in words, the relations between brush strokes and light and flesh, the technical problems posed, the difference between the mechanical and the imagined’.[13]

It has taken me a long time to get around to exactly why Byatt uses the terms ‘arrested and superficial’ of painting in comparison whilst saying the term is (or terms are) not derogatory. I think it is because an evaluation of painting always must confront how we evaluate even a master painting as other than ‘arrested and superficial’ in the derogatory sense since it stays so on the surface of time rather than developing through it, whilst this may not be required of even a bad story for the reader uses their time in reading ANY novel developing sometimes, despite the quality of a written story, cognitions and emotions from what the words in their written sequence and structure might be offering to them, to plumb the possible depths of experience through which characters grow. So with The Unknown Masterpiece. Hence in what follows I take up Byatt’s challenge to offer ‘close reading’ of this story – though in an undistinguished English translation.

In the story as I read it, Balzac’s narrator is constantly showing, through the characters of Pourbus and Poussin, how superficial is their grasp of what the function of form, colour and the techniques of painterly making is in transforming dead material into something living. Indeed, he argues they observe first not the body in its original fleshly nature they want to represent but the stereotypical models of that project in the traditions of past painting. For this is what I take Frenhofer to be saying here in his comparison – although it is not the only binary comparison he uses – as note the distinction between northern masturbatory precision and Southern Continental free and sexual style – of the techniques Vasari called Disegno and Colore (the masters of which respectively, according to Vasari, were Raphael (or Dürer for Frenhofer) and Titian.

“you have wavered uncertainly between two systems, between drawing and colouring, between the painstaking phlegm, the stiff precision, of the old German masters, and the dazzling ardor, the happy fertility of the Italian painters. … You have achieved neither the severe charm of sharpness of outline, nor the deceitful Fascination of the chiaro-oscuro. In that spot, like bronze in a state of fusion bursting its too fragile mould, the rich, light colouring of the Titian has overflowed the meagre Albert Dürer outline in which you cast it. Elsewhere the features have resisted and held in check the magnificent outpouring of the Venetian palette.[14]

It is not difficult to see here that Frenhofer constantly contrasts confined mechanical skill and talent, as in the drawn lines favoured in desegno, with something more exuberant in the flow and cornucopia of resources compared to ‘outpouring’ and ‘fertility’. Frenhofer is the enemy clearly of formalism, based on the imitation of past forms in the Old Masters, and sees both his visitors as tied into it that practice. For Frenhofer accuses Pourbus precisely of being ‘arrested and superficial’ in a derogatory sense, although the suggestion of rape in his metaphors (‘forcing nature to yield up her secrets’ for instance) so appals, I wonder at its ability to have continuing appeal:

You draw a woman but you do not see her! Not thus do we succeed in forcing nature to yield up her secrets! Your hand reproduces, unconsciously on your part, the model you have copied in your master’s studio. You do not go down deep enough into the intimate knowledge of form, … Beauty is a stern, uncompromising thing, which does not allow itself to be attained in that way; you must press it close, and hold it fast to force it to surrender. Form is a Proteus much more difficult to seize, and much more prolific in changes of aspect than the fabled Proteus; only after a long contest can one force it to show its real shape. … [Raphael’s] great superiority is due to his instinctive sense which in him, seems to desire to shatter form. … Every figure is a world in itself, a portrait of which the original appeared in a sublime vision, in a flood of light, pointed to by an inward voice, laid bare by a divine finger which showed what the sources of expression had been in the whole past life of the subject. … You produce the appearance of life, but you do not express its overflowing vitality, that indefinable something which is the soul, perhaps, and which floats mistily upon the surface, in a word, that flower of life that Titian and Raphael grasped.[15]

The pursuit of the deep that underlies or rises above surfaces and the resistance to stasis in the capture of what underlies mere formal accuracy is I think what Byatt means by praising Balzac’s understanding of painting methodologies in Portraits in Fiction and in her favouring of Patrick Heron. Yet it is also the case that Balzac wants us to understand the sexual repression that fires Frenhofer’s desire, and emerges through his language, and its transformation of aesthetic admiration of bides to power over them. This is what Pourbus explains to Poussin in saying that what Frenhofer sees as ‘perfecting his work’ is really burying it under the exaggerated cover of his own painterly abandon: ‘the variegated layers of colour, which the old artist had painted over, one on the other, …’. For creators can also be destroyers and only a ‘foot’ escapes ‘an unbelievable, slow and progressive destruction’. [16]

Byatt’s interpretation of this is however faultless in my view, for even if Frenhofer is a failure as an artist and his death and the burning of his painting is not to be mourned, his language (of course actually Balzac’s language, is the very essence of how art works, with a capacity to set time in motion: redeeming it from the past and propelling it into the future. Hence she lingers lightly (I am not of the mind of those who see her as a ponderous artist) on the layering not of material paint like Frenhofer but of cognitive-linguistic structures that work to animate time and restore deep things from their burial to the surface.

The visual image is both striking clear – a foot in a tangle, or behind a wall, of brushstrokes – and splendidly vague. Balzac adds to it precise metaphors and comparisons, which make it a myth of creation and destruction, endlessly succeeding each other – a marble torso of Venus in the wreckage of a burned city, where the marble foot is a dead beauty, even in its survival, and the emerging foot, which suggests the birth of Venus from the formless wave of the ocean. Beauty and form come together out of chaos, and are gathered into it again.[17]

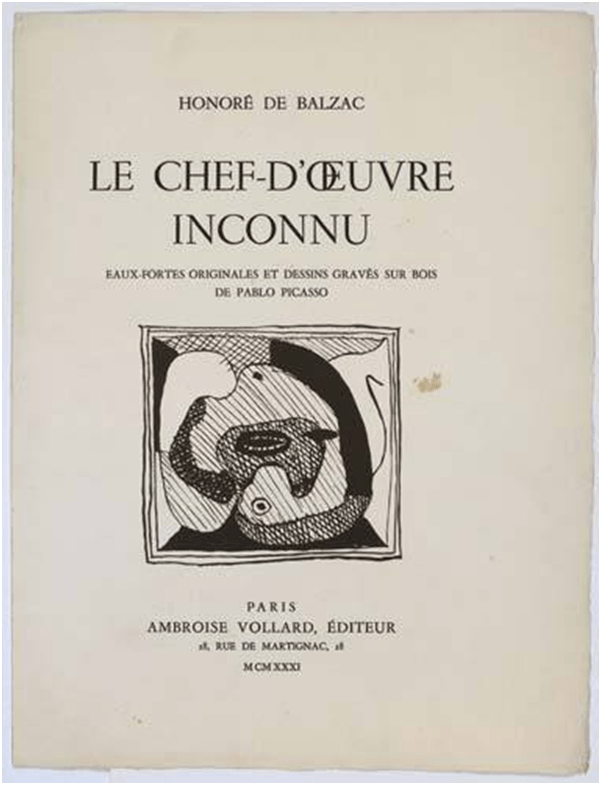

This is beautifully allusive and suggestive a prose as you will ever find, replete with echoes of past traditions but aiming at the future such that we understand that art is not mere copy but about the process of making and unmaking in which art aspires to develop from arrested states and to dive deeper than surfaces in the present moment. It is clear to me that Byatt knows that painting also pursues a similar agenda from Cezanne onwards, and hence the latter’s identification with Frenhofer. It is clear in his formal design and colour interaction experiments and in Emile Bernard’s later identification of the two, cited by Byatt, because: ‘Frenhofer est un homme passionné pour notre art qui voit plus haut et plus loin que les autres peintres’.[18] I would see it in the evidence of the work too but would get lost demonstrating that here. In relation to Picasso others have tried this because the latter illustrated a translation of Balzac’s story on the request of Vollard in 1931. Its features come out of works with similar theme: the relationship of artist and model, such as this one in Glen Russell’s Goodreads 2017 review of that reissued edition.

For this painting even shows the emergent foot from Frenhofer’s paining destroyed as soon as it as seen as drawn (it has one too many toes) and the ways in which artistic method both invites acts of perception and destruction even in the viewer’s perception, although Russell only uses this illustration rather than discusses it, although he does say: ‘And there’s that foot! Echoes of Frenhofer and Balzac?’[19] Maybe the same patterns of creation and destruction are suggestion in the frontispiece of The Picasso illustrated version:

I hope this blog has not been too meandering. You know: I get these drives. LOL.

All the best

Steve

[1] A.S. Byatt (2001: 93) ‘Portraits in Fiction’ London, Chatto & Windus.

[2] ibid: 264f[3]AS Byatt (2015) ‘AS Byatt: in praise of Patrick Heron’ in The Guardian [Sat 4 Jul 2015 10.00 BST] Online. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2015/jul/04/as-byatt-patrick-heron-the-artist-who-helps-me-write

[4] A. S, Byatt (1964: 69) Shadow of A Sun: A Novel London, Chatto & Windus.

[5] Honoré de Balzac (1899: 22, translator not named in the Caxton Edition of the full La Comédie Humaine) ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ in Honoré de Balzac The Unknown Masterpiece (with other stories) London, The Caxton Publishing Company, 5 – 46. Apologies for not using a more recent and scholarly translation

[6] Citing her Possession (1990) this is Byatt 2001 op.cit: 93f.

[7] Ibid: 1

[8] Revelations Chapter 12: ‘A great portent appeared in heaven: a woman clothed with the sun, with the moon under her feet, and on her head a crown of twelve stars. She was pregnant and was crying out in birth pangs, in the agony of giving birth. Then another portent appeared in heaven: a great red dragon, with seven heads and ten horns, and seven diadems on his heads. His tail swept down a third of the stars of heaven and threw them to the earth. Then the dragon stood before the woman who was about to bear a child, so that he might devour her child as soon as it was born’.

[9] Byatt 2001 op.cit: 34

[10] Mrs Duffy lectured on Book 1 of The Faerie Queene in my first year at UCL, whilst she was writing this novel.

[11] Ibid: 23

[12]Cited Ibid: 31

[13] Ibid: 23

[14] Honoré de Balzac (1899: 11, translator not named in the Caxton Edition of the full La Comédie Humaine) ‘The Unknown Masterpiece’ in Honoré de Balzac The Unknown Masterpiece (with other stories) London, The Caxton Publishing Company, 5 – 46. Apologies for not using a more recent and scholarly translation

[15] Ibid: 13- 15.

[16] Here I use Byatt’s own translation of Balzac cited Byatt 2001 op.cit: 27, 26 respectively

[17] Ibid: 27

[18] Ibid: 31f. Byatt also translates: ‘Frenhofer is a man, passionate about art, who sees higher and further than other painters’.

[19] Glen Russell’s Goodreads 2017 review: Available at: https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/817790.The_Unknown_Masterpiece