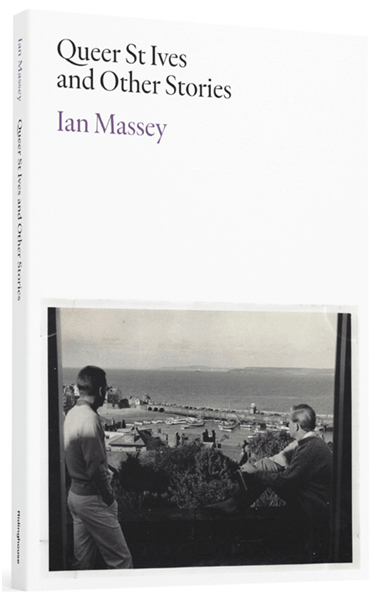

Ian Massey puts the mind of a community of queer artists and ‘others’ at the centre of his account of St. Ives. Massey constructs at one point a description of graphics, used by sculptor John Milne in his psychodynamic (Jungian) therapy, of the artist’s own ‘inner life’. His words, for me as a reader at least, also describe the beauty and tragedy of an ‘othered’ queer community for whom artistic achievement is also a goal: ‘abstract expressions of (…) inner life that, in contrast with the formal containment and smooth surfaces of much of [the sculpture described herein], read as maps of his state of mind. Usually made in (…) materials of charcoal, pastel or crayon, many are of disorientating spaces: vortexes, tunnels and dead ends’. [1] (The quotation is rewritten by me as indicated by parentheses and the italics are my emphases). This blog contends that what is achieved is a kind of beautiful and wondrous psychosocial geography indicating why queer people need that such communally local pictures of shared lives URGENTLY require writing. This blog reflects on Massey’s (2022) ‘Queer St Ives and Other Stories’ (London, Ridinghouse).

I had, without realising it I have to admit, read work by Ian Massey before I was attracted to this book because it deals with a period in twentieth-century history of visual and literary that genuinely attracts me (as numerous blogs of mine show) but also because it conceives of queer stories as the stories of a group of interacting people in one locality, one place. I will say more of the reasons I enjoyed that earlier work by Massey that I unknowingly (in as much as I registered a specific author) read. But first I want to think about the theme of localised groups in art history in a book which definitively does not queer the stories of those communities of common interest. Such, for instance, is a book by a well-known American academic art historian Mary Ann Caws. I bought her 2019 book Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism because of my interest in communal expressions of creative thought, feeling and making. On completion I characterised her project in a blog still available as using:

… previously unexplored concepts as a means of reinterpreting the history of art. For Caws the central concept is the ‘gathering’ or ‘meeting place’ for artistic groups, although it extends to the more well-trodden concept of the artistic colony. The introduction to Caws’ book attempts a synthesis based on these ideas by play with the central role of tables ‘around which given groups might assemble’. This allows Caws to focus on dining tables as well as the tables of a bar and to invent phrases to prosecute her argument such as ‘tabling places’. Short of that she imagines the exchanges between the members of any gathering as ‘talk around the table’ as a symbol of ‘the life of the arts: the turning towards and working with other creative beings’. [2]

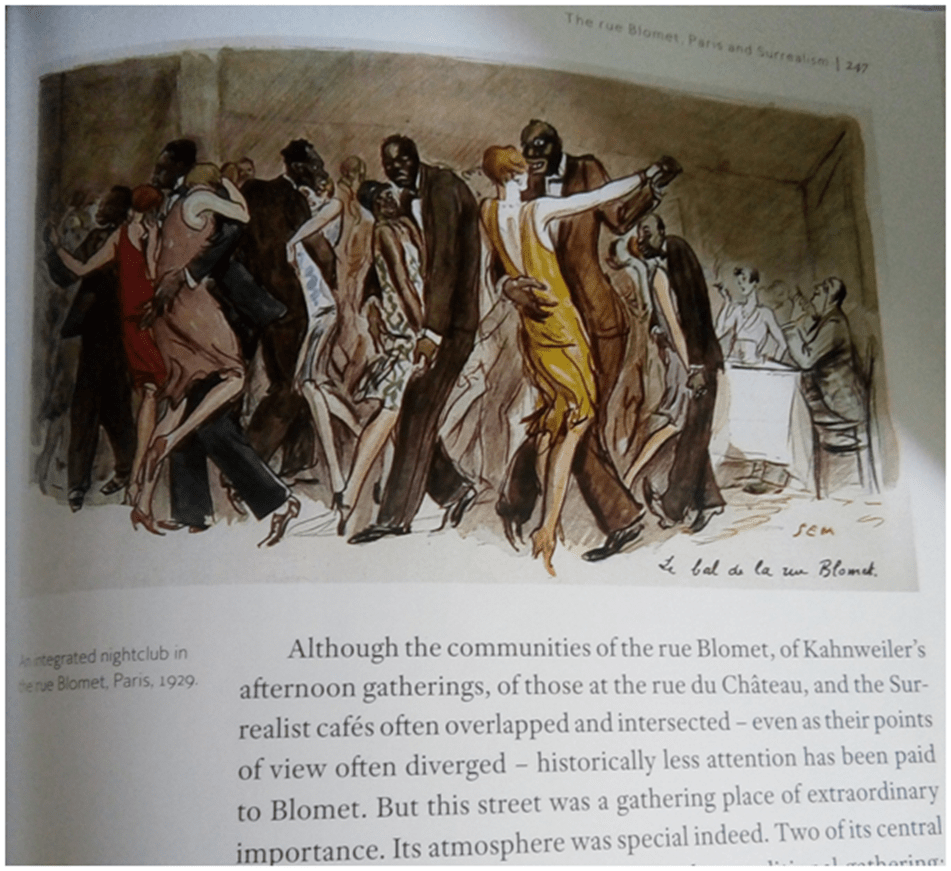

This is all very satisfying in that it widens the significance of the human prompts to art that are social and which become its subject, even in simple interior still lives. But there is something missing from the grasp of how groups work here, that fails precisely where it omits the otherness or queerness often expressed within groupings or even as their external manifesto, implicit or explicit. As I say in the blog, it makes Caws fail to acknowledge how some groups form their identity around queerness or otherness and thus miss times when these groups are being treated negatively for that reason, as when she gives, in relation to Blomet Parisian nightclubs attended by artists in which black men were represented, an;

… illustration in colour meant to represent a caption reading: ‘An integrated nightclub in the rue Blomet, Paris, 1929’.[5] I show that page below but also apologise to anyone from the black community who may chance to see it, for this not only ‘others’ black people but renders them as grotesques and sexual predators – a stereotype so close that of ‘bourgeois mores’. Yet there is no comment on this from Caws, who must have approved its inclusion.[3]

Caws’ blindness to the negation of otherness in some groups is also illustrated where she fails to attend to the inadequacy with which some artistic groupings exacerbated the oppression of ‘marginalised people on the edges of their proffered group experience’, such as the treatment of its rector, Robert Wunsch, by the Black Mountain Community College because of the twin facts that he was queer and supported the introduction of a policy in the community of ‘racial integration’.

This is a long digression but it illustrates very well the context in art history against which we might evaluate the innovative quality of Ian Massey’s group biography of a part of the St. Ives ‘gathering’, in Caws’ term. For queerness and ‘otherness’ is at its heart. Work for Massey begun as a biography of John Milne but, as he says on his Art UK page on the book: ‘Over time I realised that I was not only writing a biography of Milne, but also what amounted to a previously unexplored queer history of St Ives, in which many subsidiary queer characters became interwoven in its narrative’.[4]

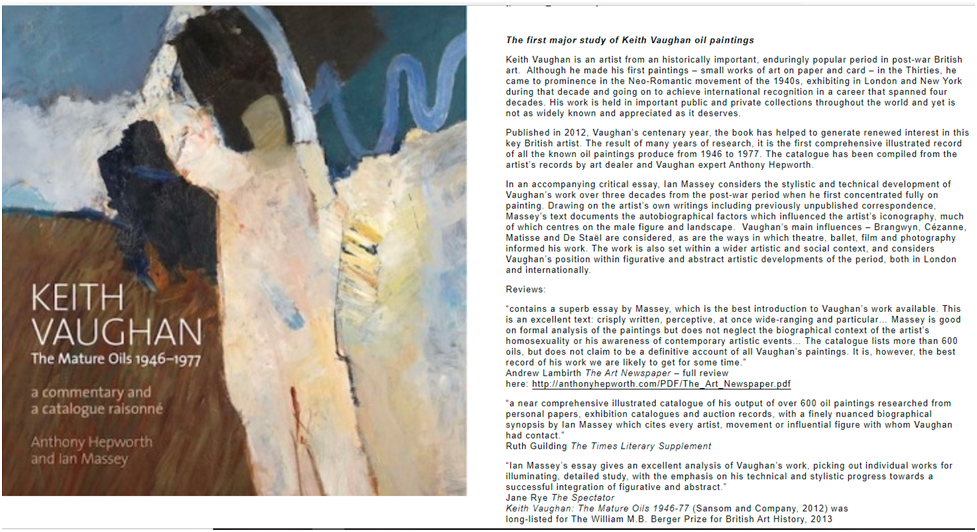

Moreover, had I been alive to art historian names I might have expected that since I was already a fan of an essay, without really registering the author’s name, in a catalogue raisonné of Keith Vaughan’s ‘mature oils’.[5] I loved it because the essay made central to its discussion the necessary contradiction between Vaughan as an innovative formal classicist in picture-making and the drive he felt that to confront the homoerotic in both defining his subjects and painterly methods. This essay, about my favourite English twentieth-century painter about whom I have read most of the literature, seemed to me be very special in the subtlety by which it pursued the well-recognised features of an academic and a committed queer approach, even if not from a theoretically defined perspective.

And, surprisingly given that Massey is candid about the lack of evidence of Keith Vaughan ever owning or renting a studio on Porthmeor Beach there (as is suggested in Patrick Procktor’s ‘untrustworthy record’ that is his autobiography – Massey is his reliable biographer), Vaughan is also mentioned as significant to the queer, as well as arts, community in Queer St. Ives and Other Stories.[6] St. Ives though merits the vignette of Vaughan Massey gives here because of the landscapes he created on the basis of his visits, to Patrick Heron for instance, and for his insightful, if sometimes rather dour comments on the downsides of dispersed rural ‘communities of artists’ whose membership is of ‘young artists living in little stone huts with absolutely no money and artistic wives and a sort of negative satisfaction of having escaped something’ who after all don’t ‘paint very well’. Even more telling is the vignette of better artists in the centre of St. Ives and its queer life, though not themselves identifiable as queer, such as Barbara Hepworth and her then husband Ben Nicholson. Of the former he writes that she seemed ‘a tightly wound spring of tension. But without a trace of self-doubt, self-questioning’, for the balance in that assessment of admiration and distance from someone truly an artist of enormous stature is evident. It seems right that comparatively all that is quoted from Vaughan about her husband is, ‘Ben just the same’. That just about captures their relative worth as twentieth-century artists in my view.[7]

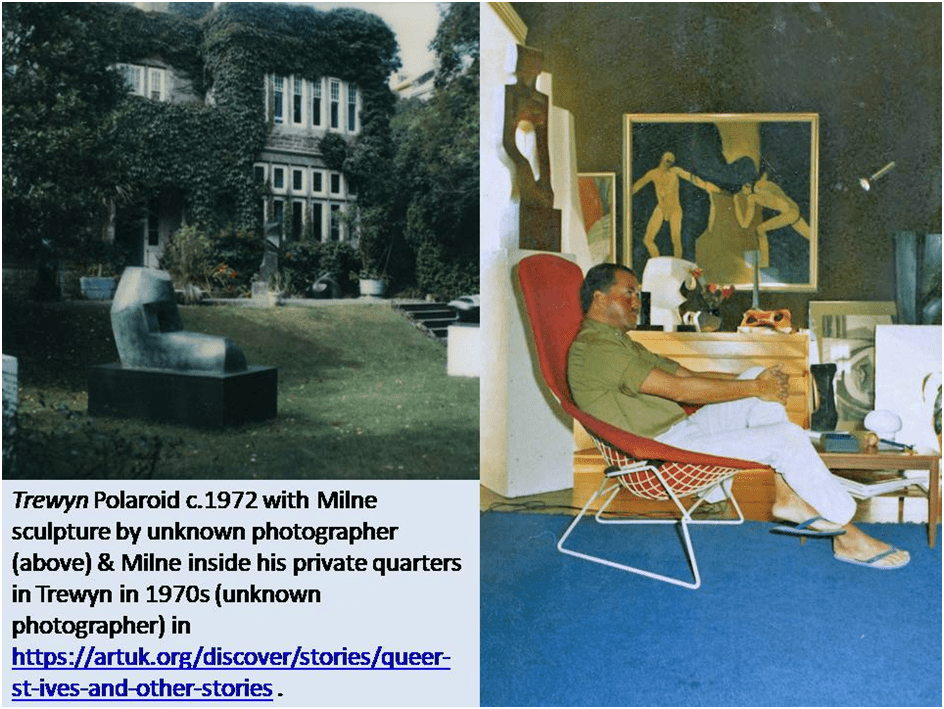

But astute (if ‘bitchy’) comment aside, Vaughan’s commentary is apropos of the great value of this book in showing the importance of otherness in queer communities – of a community that has no centrally organising definition either in art or human sexuality and amative behaviour as if it is the queerness and resistance of norms in the group as a whole that one needs to take into account, rather than search for some defining commonality. As a coda to that discussion take the fact that John Milne, at the very centre of this account, owned a boarding house named Trewyn (a name reputed wrongly to mean ‘house of innocence’ to the amusement of Milne and possibly sexually enterprising persons it boarded) but which was rather a ‘House Beautiful’ after Oscar Wilde.[8] In this house of the socially useful-aesthetic (Wilde’s contradiction but deeply meaningful in this context) was one of Vaughan’s finest mature oils, shown below behind Milne: Fifth Assembly (Two Figures In Sequence) 1957-8. This painting is itself, in my view, about the dream of human / queer communion (the duplicity here is important and not just a mask in Vaughan whose thought always touched the senses and questioned boundaries between people by these means) amid inevitable disruption and the necessity to tunnel through disorientating space that surrounds all human relations.

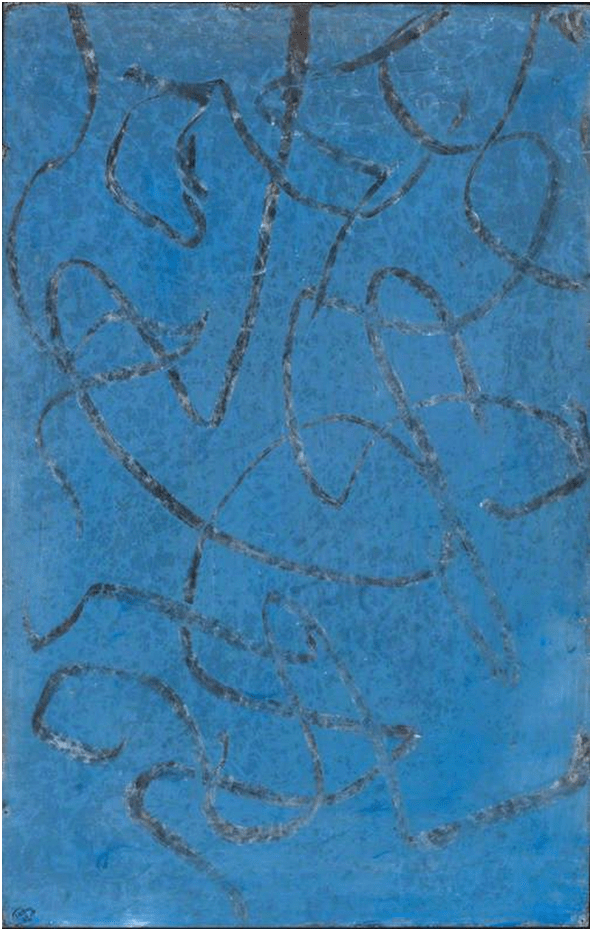

Hence, I think we need to allow Massey’s book to widen our sense of what is queer and what is ‘other’ to norms, what is art and what is encoded desirous yearning that is barely sublimated, and what is evident in accounts of St. Ives life and what has to be unearthed. And more than that, as Vaughan’s experience showed – what was allowed entry into this community and what not. There is an excellent section on ‘encoded desire’ as a response to the marginalisation, which deals with semi-private languages like Polari and the hints associated with assumed classicism and the pastoral in the painting movement called Neo-Romanticism. Of course this was the case, though ‘the signs are by definition more complicated’, although not in the case of Mark Tobey, an American, whose sense of ‘inner space’ in art clearly builds in codes for queer sexual congress dominated by phallic shapes and orifices, sometimes in penetrative relationship, otherwise merely in sense contact.[9] Of course such readings can be denied in abstract art but that perhaps is part of the game of ambiguity in art that promotes disorientation space for ‘vortexes, tunnels and dead ends’ are the stuff of those displaced from the norm[10].

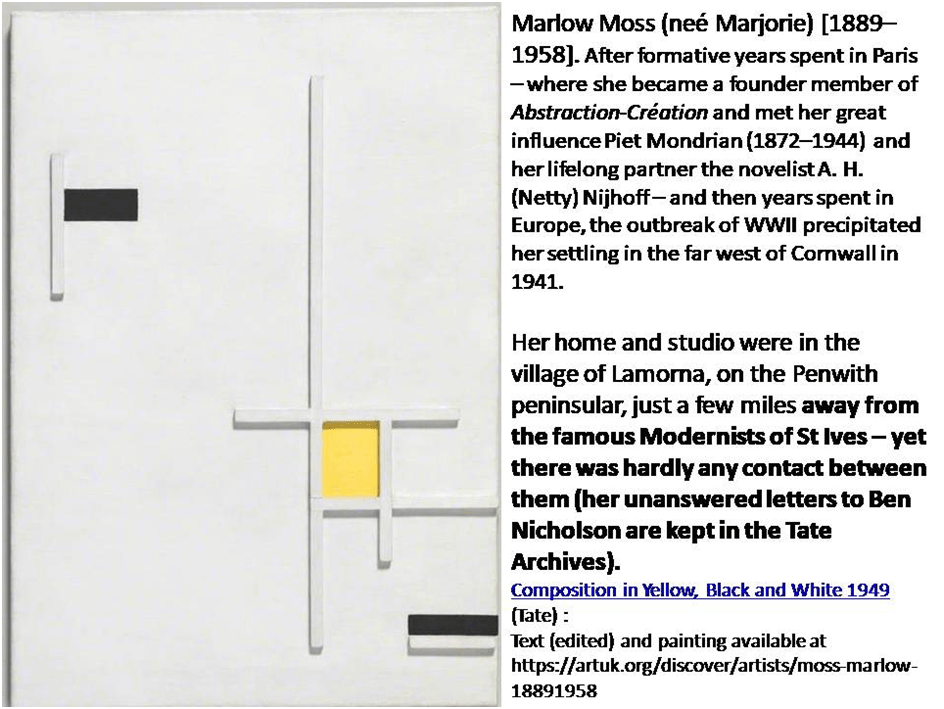

Yet, if Mark Tobey was welcomed in as a guest resident of Queer St Ives, Massey shows this is not true of others such as the modernist Marlow Moss, who was a lesbian and follower of Piet Mondrian, who was welcomed to St. Ives circles, queer and other. For despite the fact that Moss’s work bears some family resemblance to that of Ben Nicholson, her letters to him and Barbara Hepworth remained unanswered.

Yet this work too plays with notions of confined space and absence, such as must have been Moss’s experience. Massey interprets this as possible evidence for professional jealousy, stating that they saw her as an ‘interloper, a threat to the primacy both in St. Ives and beyond, for her links to the avant-garde were every bit as strong as their own’, since her professional friendship with Mondrian pre-dated theirs. After Moss’ death, Hepworth spoke of Ben Nicholson’s, in particular, and her own right to be ‘paid tribute’ for their ‘contribution to the international links in England via Paris’. [11]

These stories tell of a ‘queer’ and ‘other’ community that was more torn by hidden conflict than it liked to present itself and nowhere is that clearer, as Massey tells the story, than in the ways in which queer communities, who felt embattled against a hostile outer world, sometimes valorised their isolation and marginalisation as if it were without internal conflict, when it was evident it was. Milne could glorify the fact that he could secretly attract the attentions of an unwitting ‘young farmer’ and spend the night with him. He wrote to his friend, Julian Nixon, of the latter’s joy on the same night with a policeman who ‘sounds divine’ but had to warn Julian to ‘remember all the stories one hears of police confidence tricks’.[12] Perhaps more telling in their effect are the stories of the suicide of queer men (or those associated with the queer St.Ives like Eddie Craze who ‘gassed himself’ for reasons still unknown) which do not suggest that internal support in queer communities was always as strong as it might be described, especially for a local Cornishman like Eddie, whose association to the St.Ives group may as we shall see, ‘tarred’ his local reputation. Some of the St.Ives’ group’s life-events are fictionalised in a short story by Norman Levine called ‘The Playground’, in which renamed portraits of well-known local characters were recognised by many, including Julian Nixon, who tried to sue Levine. He named Eddie (not, we should note, gay as as far as Massey’s research shows), ‘Starkie’ but he also revealed that working-class St. Ives locals were suspicions of Trewyn, Milne and other ‘artists’ associated with queer goings-on for he reports gossip to this effect that young local Starkie:

… really wanted to become a painter; that he was becoming homosexual; that he realized how corrupt he had become. … And in the Back streets Cornish parents used Starkie’s death as a warning to their restless children to “keep away from them artists”.[13]

Eddies’ story, as reported by Levine at least, supports Massey’s point made several times that fears (of the size of a moral panic) of queerness as a social contagion existed alongside a belief in the queer artistic community that there were no issues of prejudice in St. Ives. It may have been part of a helpful myth to believe that John Milne just ‘fitted in’ and that: “People’s sexuality was 100 per cent accepted by everybody, even the fishermen”.[14] However, Massey elsewhere quotes a judge in a case in The Times in January 1954 promoting a common view of the period that ‘once vice got established in any community it spread like a pestilence and unless held in check threatened to spread indefinitely’.[15] As Massey says therefore it is questionable ‘how deeply this liberality ran’. For instance a heterosexual man, Reg Singh, who stayed at Milne’s Trewyn was ostracised for a few days by his girl friend and her family ‘because it was so infamous, the place, she just thought I was gay’.[16] And even Milne called an ‘Australian Queen’, who was visiting St. Ives, ‘idiotic’ and a fool because, after a ‘severe assault’ from two youths, he ‘admitted in court last week, that he is homosexual! Fool- the one thing one should always deny’.[17] That Milne spoke of another queer man, one not aware of the extremities of English anti-queer law, with so little empathy for mistakes, calling the assault merely a ‘beating up’ though the man’s skull was fractured and his head lacerated, suggests that internal support in queer and other St. Ives had its limits and conditions, even if, in the legal circumstances, these were understandable. It is still not acceptable to ‘blame the victim’ for their own oppression.

Another ‘story’ can be queried for its possible folk-myth status in queer history: the idea of the pre-1967 ‘gay world’ as ‘a world of tacit understanding and support operating outside the usual strictures of class, in which “nobody asked questions; you were always welcome”’[18]. Such stories have a basis of truth and can be found in stories of London life that surround people as different as John Lehmann, Lucian Freud and Francis Bacon. Massey reports that the latter’s behaviour, to Cornish people at least, screamed a very different ‘metropolitan queerness’ to the more outwardly suppressed kind of Milne in Trewyn.[19] Yet in each of these cases, although arguably less in the case of Lehmann who published working class writers who may never otherwise have been published, working men could easily become exploited because of their relative lack of power, as in Rodney Garland’s novel, about which I have previously blogged (use the link to read it).

In St.Ives artists could boast of their working-class origins, although sometimes without conviction as in the case of Hepworth. It was clearly so in the life-stories of John Milne the sculptor and Tony Warren, the novelist and screenplay writer (of Coronation Street fame eventually), as told in this book. Their common background in Manchester is given prominence, whilst Keith Barron, the actor, was later also attracted to this feature of social life in St. Ives.[20] Some working-class gay men claimed a special status for St. Ives in terms of its indifference to class origin; such as Brian Wall who said of his own experience as a working class man that “class differences weren’t allowed” in St. Ives.[21] However, like Hepworth, John Milne cleared his voice of signs of a regional accent – a very important indicator, in the world of Received Pronunciation, of class origin.[22] These stories are all the more felt in that they are clearly a mark of author’s identification with a ‘gay working-class lad’ entering a world marked by class and elite distinctions that came with ‘high art’.[23]

Perhaps though the key marker in this book is the fact that survival as either queer or other, physically in body, or economically and socially was never certain and that the chances of becoming the victim of a society that othered you were great even if ones status as different had its compensations. Milne, we are told, made so many suicide attempts that friends tried to mitigate his condition by financial support.[24] Indeed his death eventually was suspected to be possible suicide, although that was not the coroner’s conclusion.[25] Yet after death not only were queer lives cleared away in the record of their possessions but also by heterosexual family arriving to dispossess lovers and sanitise the deceased’s ‘homosexual history and losing evidence that might prove embarrassing to’ the family or the artist’s reputation.[26] Massey tells us that Milne marked many passages in his favourite books not least from Jan Morris’ autobiographical account of a transsexual life, Conundrum. Massey cites this because it brings us back to the metaphor of outer space as a means of confronting the more puzzling (and hard to reconcile with external norms) phenomenon of a queer inner life, out outside norms by definition: ‘I spent half my life travelling in foreign places … I have only lately recognized that incessant wandering as an outer expression of my inner journey’.[27]

From this we recognize the finely structured nature of this story of communal life – geographically, socially and psychologically – in the quotation describing Milne’s mind graphics in my title: ‘maps of his state of mind … disorientating spaces: vortexes, tunnels and dead ends’.[28] Do read this book it is beautiful. This autumn I visit a Barbara Hepworth retrospective. It is possibly the one I saw before, loved and blogged about (see link) but I go armed with new eyes thanks to Ian Massey. And I have yet to read his biography of Patrick Procktor, which is on its way. Yay!

All the best

Steve

PS. Many thanks to Andrew Massey for helping me correct some misunderstandings of his book. In an earlier draft I had said that Julian was the ‘sometime partner’ of Milne. This was not the case. I had also reported and implied that he had said that Eddie Craze was gay. In fact, as Massey has emphasised to me, he found no evidence of that, through arduous research. Speculation in Levine’s short story about Craze’s fictionalised persona, Starkie, was merely that. I am immensely grateful that Andrew Massey corrected me and even more so that he did it discretely with concern for how it may appear in public. A true gentleman as well as a scholar. I hope my ‘corrections’ are okay.

[1] Ian Massey (2022a: 29) ‘Queer St Ives and Other Stories’ London, Ridinghouse. The quotation is rewritten by me as indicated by parentheses and the italics are my emphases.

[2] My blog on Mary Anne Caws is linked here.

[3] ibid.

[4] Ian Massey (2022b) Art UK webpage on Queer St Ives and Other Stories Available at: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/queer-st-ives-and-other-stories

[5] Ian Massey (2012) ‘Walled Gardens: Keith Vaughan paintings 1946 – 77’ in Anthony Hepworth & Ian Massey Keith Vaughan: The Mature Oils 1946 – 1977: commentary and comprehensive catalogue Bristol, Sansom & Company Ltd. 8 – 40.

[6] Ian Massey 2022a op.cit: 171-3

[7] Vaughan cited ibid, respectively, 173 & 172.

[8] Ibid: 72f. In fact Massey tells us that Trewyn means, in derivation from the Cornish, ‘White House’.

[9] Ibid: 195 – 8

[10] ibid: 29

[11] ibid: 65f.

[12] Ibid: 121

[13] Ibid: 119f.

[14] Ibid: 104f.

[15] Cited ibid: 81

[16] Ibid: 106

[17] Ibid: 105

[18] Ibid: 45 My italics.

[19] Ibid: 97f.

[20] Ibid respectively: 24ff, 32f, 175.

[21] Ibid: 161

[22] Ibid: 210

[23] Ibid: 18

[24] Ibid: 183

[25] Ibid: 217

[26] Ibid: 218

[27] Cited ibid: 190

[28] Ibid: 29

9 thoughts on “‘abstract expressions of inner life that, in contrast with the formal containment and smooth surfaces of much of [the sculpture described herein], read as maps of his state of mind. Usually made in materials of charcoal, pastel or crayon, many are of disorientating spaces: vortexes, tunnels and dead ends’. This blog contends that what is achieved in Ian Massey’s new book is a kind of beautiful and wondrous psychosocial geography indicating why queer people need that such communally local pictures of shared lives URGENTLY require writing. This blog reflects on Massey’s (2022) ‘Queer St Ives and Other Stories’.”