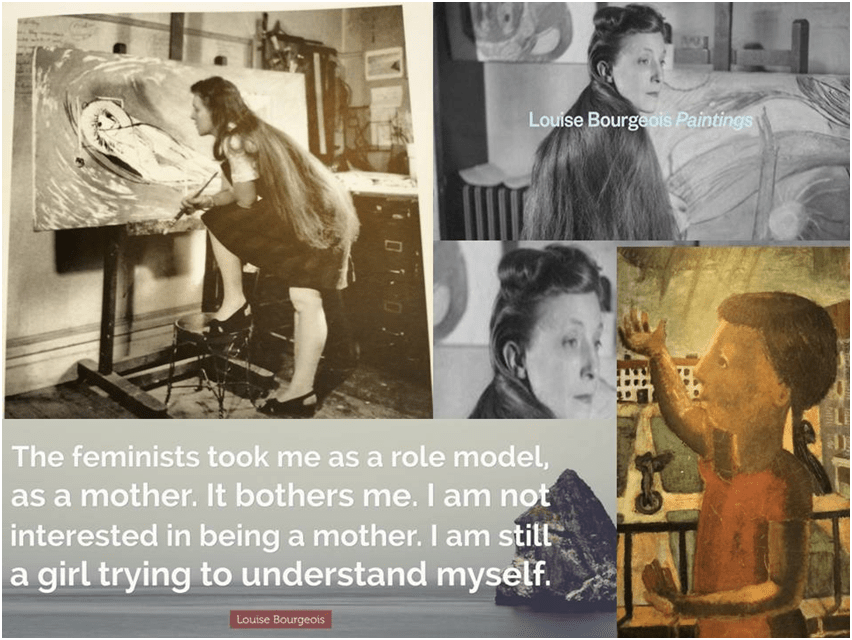

Briony Fer, in an essay in the catalogue of the latest retrospective of Louise Bourgeois’ paintings at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, says Bourgeois abandoned painting when painting itself abandoned the representation of an external world and its phenomena in the view that ‘the most ambitious art had to be abstract and obey certain pictorial protocols – an opinion that, with all such doxa, was fundamentally exclusionary and to which she never adhered’.[1] This is a blog on Clare Davies & Briony Fer (2022) Louise Bourgeois: Paintings New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art with Yale University Press.

Not a single review of this exhibition that I have touched upon has not statrted by pointing out that Bourgois is currently not known for paintings and somehow invoking from this opening a reference to her better known spider sculptures. Hence this exhibition which Clare Davies says is of paintings that have ‘never before … been exhibited together or considered in depth as a coherent body of work’: those produced on her first arrival to New York in 1938 to 1949, ‘when she stopped painting and turned her attention more fully to creating three-dimensional work’.[2] Inevitably the show must evoke both the biographical which explains the alienation involved in being an émigré in the United States just before the Outbreak of the Second War in Europe and the artist context in which for a time during and after that that war in which the USA took active hegemonic lead in directing the trends of modernist art from an ailing and occupied France. All of these issues matter but I think it a great achievement of the curators of this show to refuse to turn the paintings into a locus to mine the meaning of symbols, although some of this is inevitable and to pay attention to the material act and product of painting including a refusal of the idea that painting unlike sculpture is an entirely ‘flat’ form of art marked only by figures and their role or absence in the compositional design of the picture.

In contrast to that approach, Clare Davies uses the term ‘palimpsest’ to describe Bourgeois’ method as a painter to describe the the layering in her work and overlap of ‘artistic influence’ and ‘wide-ranging, in-depth, and up-to-date knowledge of art history and practice’. But that more metaphorical use of the term to show the interplay of ideas about art also applies to to their character which is ‘inherently material in nature’, and is about the different ways in which the surface of the canvas or other medium has paint applied to it, cut or partially scraped away and then reapplied by another layer, and perhaps colour, exploiting the variable thicknesses this creates that cannot be called ‘two-dimensional’. It creates ‘a sense of shallow depth … through the layering of semitranslucent washes of color through which graphic “underdrawings” come in and out of focus’. For this reason Davies sees a full revelation of the experience of the art only possible when the ‘subtlety of these surfaces‘ is viewed ‘in person’.

Since the chances of going myself to New York are nil, inevitably much will be missed in this piece but I am thankful for the heads up to this fact given by Clare Davies. Sometimes we must miss out on the fullness of some cultural experiences because the pragmatic and contingent are with us as persistently as are the causes of poverty under the present global economic system.

Hence I will pay attention to how her art, in Briony Fer’s words, refused to claim ‘autonomy’ from the ‘world she inhabited’, as it was claimed Rothko, Newman and Pollock did by attending only to the design of an expressively designed whole independent of that world, communing only intersubjectively and through abstraction with the real world. She may have disliked being a feminist role model, as she famously said, but she continued to query the psychosocial meanings of the feminine in relation to inequalities of power, but from a position that was experiential rather than authoritative; ‘a girl trying to understand myself’. Briony Fer expresses it beautifully thus: ‘She had always been more interested in pictures as psychologically freighted images than as expressive abstract surfaces’.[3] I myself however would have used the phrase ‘sociopsychological freighted images’ for these are images that confront the external world in its interaction with the intra-psychological one, making queer images from that interaction.

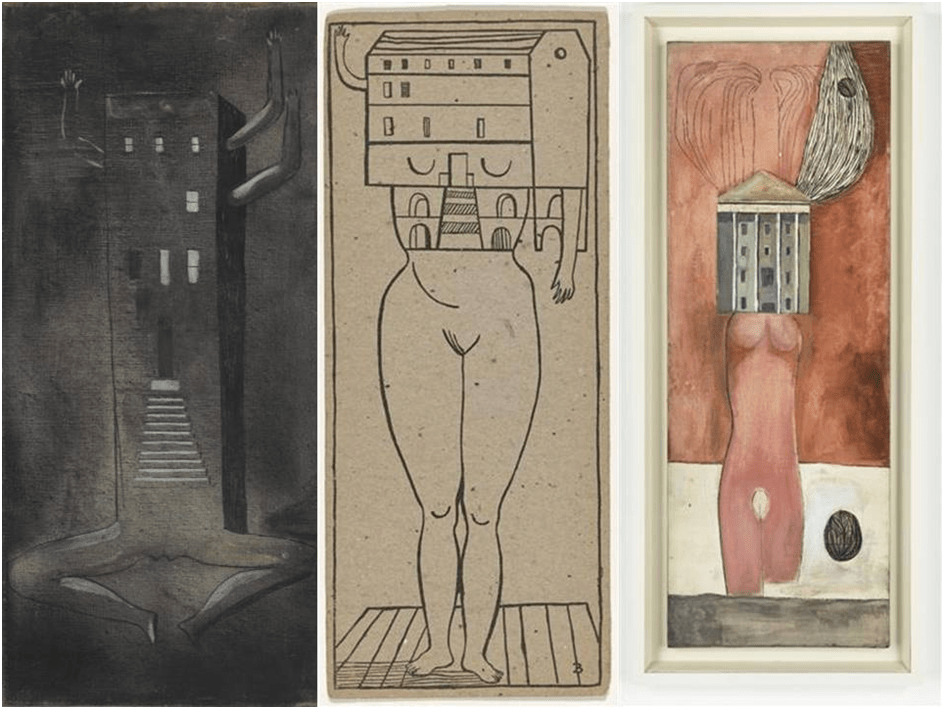

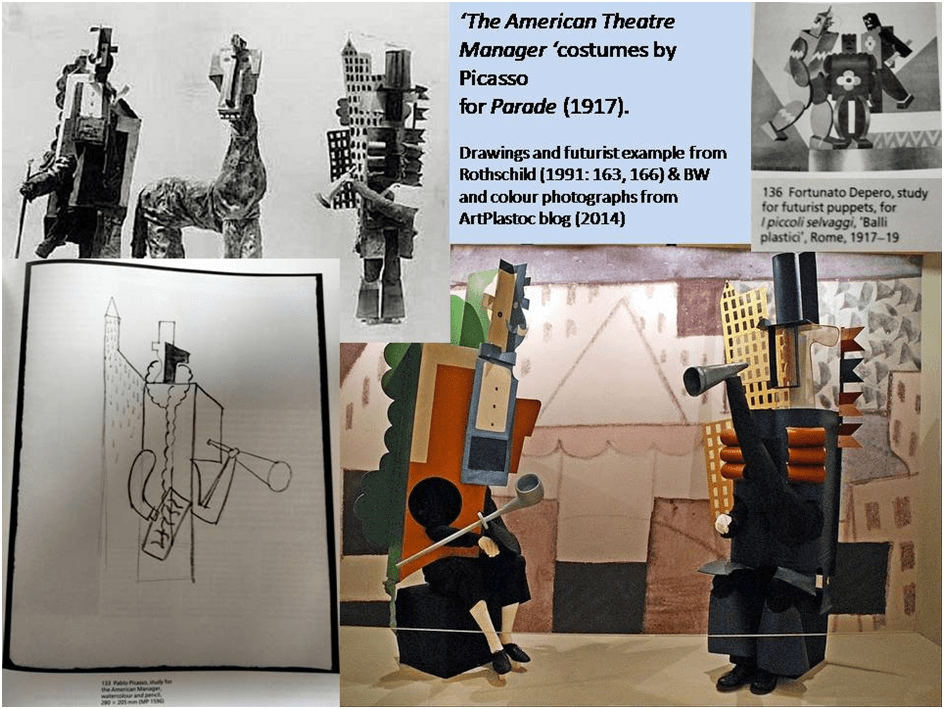

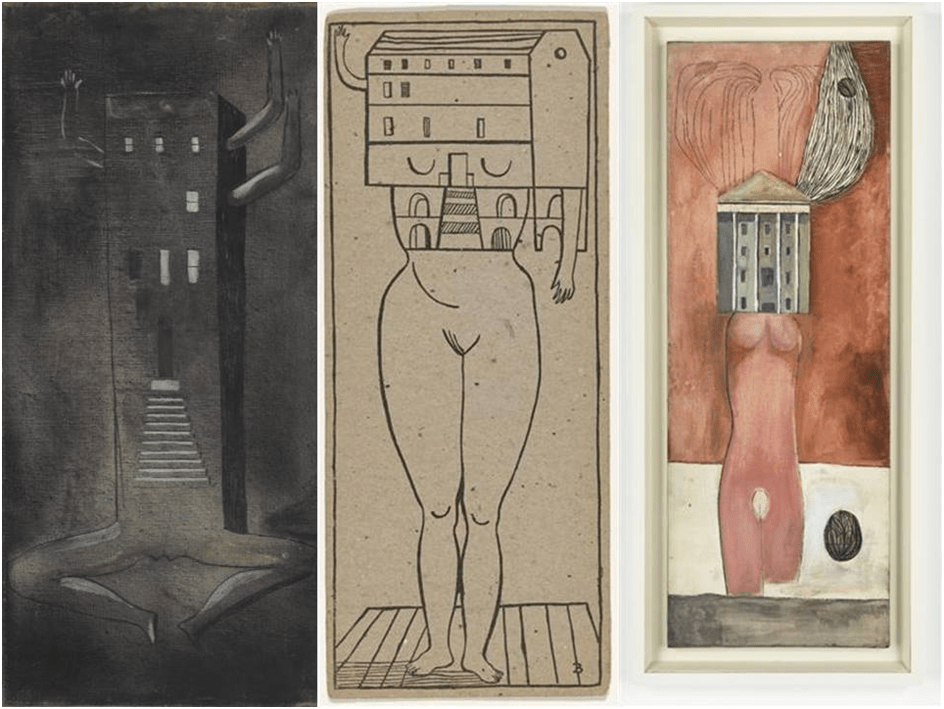

It’s that idea I will try to illustrate in examples from this exhibition’s book and catalogue. An ideal place to start I think then is those paintings that Bourgois later grouped together under the title Femme Maison (1946-7) but first exhibited at the Norlyst Gallery in 1947. Briony Fer describes them as ”body-buildings”, ‘highly anthropomorphic figures’ that ‘are also performers in costume, acting out roles and parading their artifice’.[4] Sometimes this is read, as she suggests as being part and parcel of the surrealist art movement in America, but Fer shows, the example of Dorothea Tanning, asserts that her work is far from using what she calls ‘the iconography of the dream’, which the surrealists believed themselves to have learned from Freud.

Looking at the three examples from the exhibition mounted above I think myself that the motifs used are both highly cognitive and emotional in their content but not as in dreams where context and setting are also all important matters in the interpretation of the iconography. These are symbols which reach into imagery from the social and the emotional world, proposing ideas and emotions that are complex but which asks us to read out their meaning even from their surface or manifest content tather than assuming a latent level of content as in dreams. The figures genuinely proclaim themselves as demanding to be understood, because they act out their meanings like the ‘performers in costume, acting out roles and parading their artifice’ that Fer describes. The nearest analogue to this, though not one invoked by Fer, I can think of are the characters in Jean Cocteau and Erik Satie’s 1917 ballet Parade as visually realised by Pablo Picasso under the possible influence of in preparatory drawings of costume in setting, like the American Manager whose embodiment is partially that of the built environment.[5]

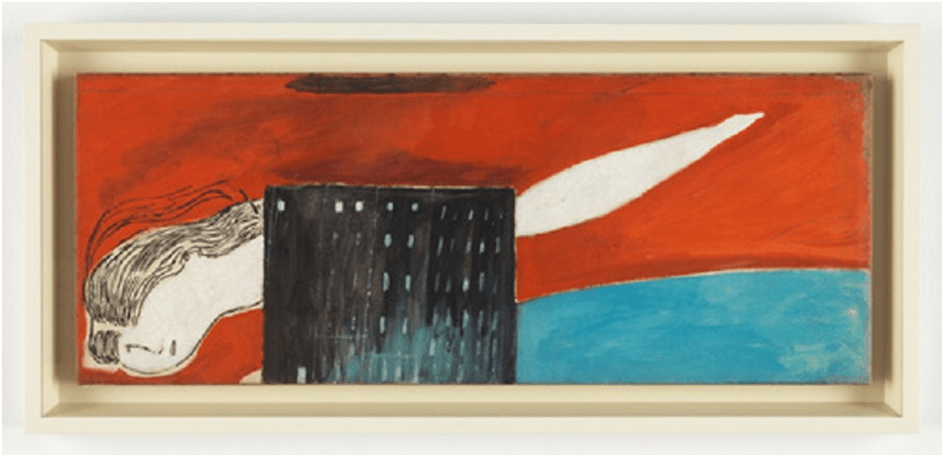

In Bourgeois’s case the ideational content is clearly that arising from the manner in which femininity is psychosocially constructed, linking it to the acted out examples of entrapment and escape, sometimes by suicide (as in another picture from the set, originally called Fallen Woman (1946-7) but later brought into the set named Femme Maison, which foregrounds a dour prison-like building from which the woman (pooled in a variegate bloody redness) with a flash of blue sky beneath it, as if seen in the act of falling. Of course the sexualisation of female bodies is also conveyed here. It is chilling.

In the three pieces I started with we see a similar sexualisation that describes women in terms of portals – doors and windows used for access and egress, sometimes to death in the case of high windows used for suicidal intention, from which in the pictures arms and legs hysterically bend (Bourgeois would have used the reference to hysteria precisely with an eye upon Freud as discussed in an earlier blog). These are in rhythm with body parts too, although the vagina in the case of the first of those below has been translated into a high black open hole of a door to which steps lead the eye upwards from the space between the legs, which are in a falling posture. Both door and steps and visceral vagina are in the second and third picture. The tenement apartments in that second also indicates icons for closed depressed eyes and too many open portals in its base. Moreover, the building-woman is enclosed in a frame with a panelled floor that doubly imprisons her showing how art sometimes itself colludes with female entrapment, as indeed Bourgeois must have felt it did in the macho environment for art being built by the Abstract Expressionists, which queer male artists like Grant Wood were oppressed by (as I cite in a blog on that latter artist). The picture communicates through patterns of open and closed access to spaces and contrasts in the symmetry and asymmetry of the ordering of things, such as the windows on the buildings for instance. In the first instance windows are also either lit or dark, which in itself plays against the tonal darkness of the whole.

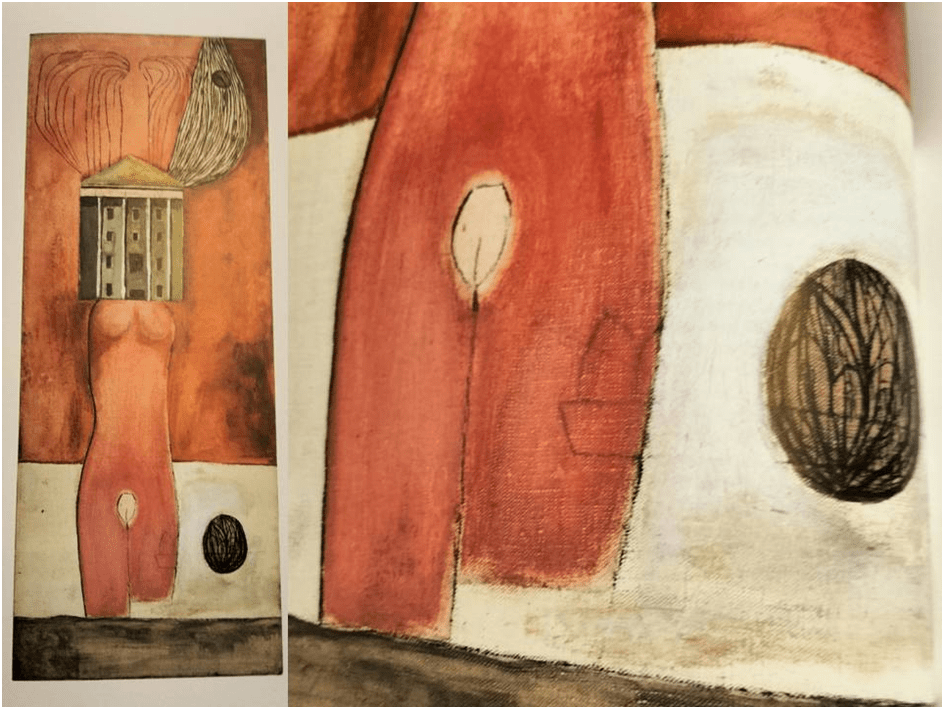

It might be worth considering however some of the differences in the third picture which uses colour rather than merely tonal contrasts in black, white and grey in the fitst or monochrome lines, hatching or shading. Moreover, it evokes forms not found elsewhere in the Femme-Maison group. These notably are shapes with curved or circular perimeters and sometimes variously filled with figures that are contained therein – often with a sense of cramped fullness. Of these paintings Wikipedia, citing a source in the Tate website that seems to have changed, says: that the figure “does not know that she is half naked, and she does not know that she is trying to hide. That is to say, she is totally self-defeating because she shows herself at the very moment that she thinks she is hiding”. This gnomic explanation is another riff, in my view, on issues of what is open and what is closed. The house encloses her head and consciousness with the security that ideas of ‘home’ convey and blinds her to her sensual and sensuous nakedness. Deborah Wye in the commentary on this painting from the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York says:

…she was raising three small boys, and so she was certainly thinking of how she felt trying to be an artist and also a stay at home mother. She chose architectural imagery to, in effect, suffocate this woman. It’s kind of dire, in a way. But on the other hand, the woman stands very upright with a certain dignity. And we can tell it’s a self-portrait because the hair that comes out of the house was a signifier of Bourgeois’ own long hair.

Architecture was a motif she used throughout her career to symbolize her feelings. She saw architectural structures as a place of refuge. On the other hand, she saw that an architectural structure could also be a trap.[6]

Of course given Wye’s second paragraph quoted here the notion that the house only ‘suffocates’ the woman lacks nuance, for safety and refuge was also an important emotional association for Bourgeois and perhaps for many other women. The dignity of the figure’s stance is perhaps Wye’s recognition of this nuance. I am less happy about the evidence used to suggest this is a self-portrait, although the long hair is an important feature of this picture, forming shapes that could be wings, although their variation between faint transparent outlines and white solidity escape my ability to interpret them, as does the circular shape in the white wing.

However I find the filled oval in the bottom half of the picture more interesting. In shape it recalls the oval at the figure’s vagina and may, I believe, represent the pubic hair that was so often not represented in female nudes in art and here has been, almost surgically detached from the icon representing the figure’s hairless sexual organs. Here is a clue to the fact Bourgeois here, as elsewhere, is contrasting girlhood to womanhood, ideal male representations of womanhood and a more reflective and accepting acceptance of a woman’s body that rejects the necessity of stereotype and embraces adult sexuality as belonging to women and not merely to men. I can but just speculate.

Wye also comments on the importance of this image in feminists taking Bourgeois to heart in America and this is right and proper and persists because the psychosocial themes are precise and pertinent to the genesis of female powerlessness in patriarchal society. However, I think the works also suggest that Bourgeois’ interest was heavily nuanced and aimed particularly at how girls become socialised into the pairing of safety with entrapment in patriarchy. Looking at Bourgeois’ other pictures that interrogate the theme of the house is then my next stop in this blog, beginning with (since selection is absolutely necessary) a haunting painting of 1941 that, like so many others is named as Untitled.

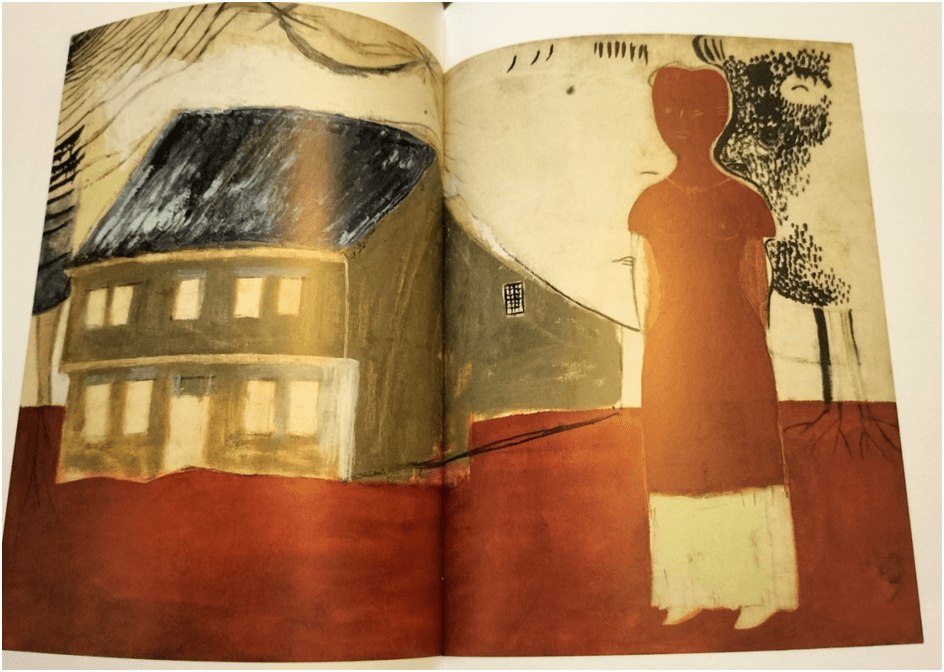

I call this painting haunting because of its deliberate distortions of objects and background. This even seems to suggest presences that are not transformed into forms in the painting such as the outline of figures on the viewer’s top right that obscures some of the tree that has been described by dabs of black. In the ‘tree’ itself, which seems to fragment into formlessness at its top there is suggestion of a face in a filled black form with emergent eyes and mouth. The figure’s face is naively drawn, as if in a child’s drawing and I think the painting as a whole recalls that idea. The house seems radiant through its windows and door space with a light greater than the background. Its rich colours contrast with a landscape that is variegated red like blood spilled on its ground, tonally contrasting with the figures upper clothing and face. My own feeling is that here a girl senses her future regulation by menstruation and its suggestions of adult sexuality. The house by the way as well as having open portals also has a barred window at its rear – clear hatching effects not seen elsewhere.

The house in Confrérie (ca, 1940) is discussed on the webpages relating to the exhibition and it is worth quoting:

Confrérie is one of the first works in which Bourgeois employed the motif of the house and path in a rural landscape. It is also a family portrait. Describing the composition to curator Deborah Wye in 1992, the artist identified herself as the third figure from the left, next to her parents. Her brother, isolated, is at center, and her sister and brother-in-law are on the right. Explaining further, she said: “The figures are in limbo . . . they roam around together in the shadow.” The ominous storm cloud over the house alludes to the turbulent dynamics within Bourgeois’ family. She considered her early paintings, many of which referred to her childhood in France, as “nostalgia pictures.”

If that smaller central figure is Bourgeois, she presents herself in Confrérie as a girl with her elders but also as somewhat remote from them. They wallow in blood-red colouration underlying the area of a well-lit house and garden. The house is like a vista of refuge and safety, something that explains why it is enwrapped with light – even if the light is presided over by cloud and gloom, streaked only with a rare bit of blue. This more than any other image illustrates the artist when she said that she ‘was still a girl trying to understand herself’.

In many paintings, rooms do the constraining of the feminine as in Untitled of 1948 or thereabouts but this is an image impossible to reproduce so dark is its palette and subtle its tonality. Suffice it to say that it remains ambivalent since the room frame disguises the shadow of a tree trunk, branches and an open night sky. Its emotional and cognitive effects interact and stun.[7]. A much darker (emotionally and in colour contrasts and tones) of the sense of feminine entrapment in a room is in a work that already leans out to predict the sculpture with its three dimensional forms enclosed in cages or prison-like rooms. It is Six Fifteen (1946-8) depicts, presumably, a time when women expect the return of male partners that have distorted them, even in their absence to mechanistic forms and hard angles and a nervous stance and stare. They look in part like the household cleaning implements that they handled all day.

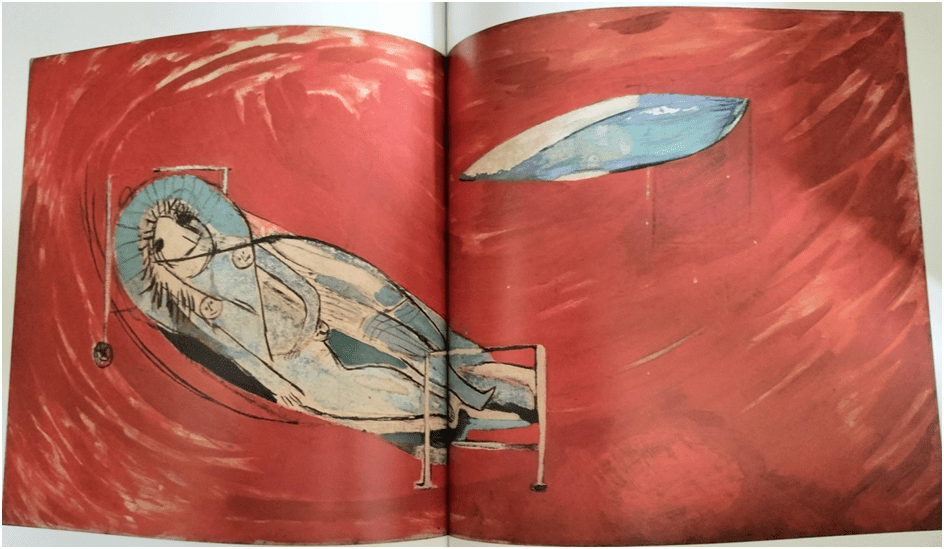

Of course the classic expression of these issues is the 1945-7 painting Red Night. There is little there that does not seem dark. The room appears like a distorted eddy in a pool of blood, with its most intense red near the bed upon which a mother cradles her children (Bourgeois herself identified this as herself with her own children). At a near right angle to the bed is a shape that is identifiable as a coffin but filled with a variegated set of blues but recall a skyscape. It is an intriguing picture that I have not got my head round for there appears to be a smile on the face of the female figure. Her children are reduced to three faces, two of which might represent her breasts – one smiling, one glum (Melanie Klein’s good breast, bad breast dichotomy relating to infantile anxiety about the availability of the mother?) and one appearing in the distortions of the drawing of her vagina. In the story told this picture represent Bourgeois’ fear of threat inside her own home, but that seems to me too simple. This may chime though with Shanti Escalante-De Mattei’s view in an online review of this exhibition for Art News, gleaned presumably from her interview the exhibition curators, that it is ‘A self-portrait in which she and her three sons are hiding in a bed together in a sea of turbulent red, the work was inspired by her recurring dreams that she and her children were in danger’.[8]

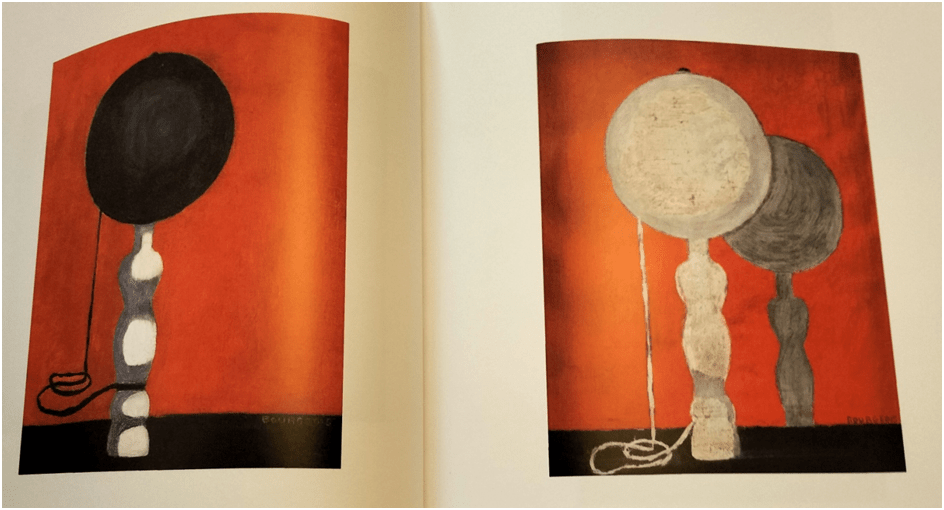

Feelings and thoughts about home interiors are often channelled in Bourgeois’ works through objects of use or play: the most intriguing being the two paired Bilboquet paintings of 1946. I refer to them as (from viewer’s left to right) A & B respectively.

When I first saw these paintings what I saw (not immediately knowing the meaning of a bilboquet) was a pair of table lamps – one (B) lit internally and casting a light a shadow behind it, and another (A) with the light off off bur receptive of external light from the viewer’s right causing the left of the sculpted handle to be in shadow. Was I seeing ineptly or just ignorantly? Here are the paintings:

Of course the items are cup and ball play toys and to Fer this is an example of her ‘simplest figuration’.[9] However my error, given the absence of title makes me see this as if intentionally more complexly even if this point is not, conclusively, at least, proven. It again raises the issue of a girl’s perception of the world, including effects of the motivated distortion of perception, for the handle shapes of the toy variously represent the type of a code for a ‘normative’ adult female body, especially in the grey double of the toy in B. That ‘shadow’ (if that is what it is) is behind the representation of the toy which stands on the ground painted in black. It is as if the shade of the toy is painted on the red (wall?) surface. Here viewing the layering of the original painting might matter. However, beyond such distortions are others concerned only with the logic, or its absence, of the design of representation. For instance if the black stripe represents the ground on which the toy stands as I assumed above, why is the cord in A, lying not on that stripe but suspended above it, yet as if lying flat. Indeed looking at these pieces together, the issue seems to be one about whether it is ever possible to conceive of a simple figuration as implied by Fer.

My own feeling is that this a painting problematising the ways in which child’s play initiates a child, in this case a girl, in integrating her feelings and thoughts with perceptions of the ‘real’ world, including her expectations of her future self as a woman. After all, as a scholarly note to this book says: ‘Toys and games also had a currency within the late Surrealist context, in which childhood had become a calling card for the movement …’.[10] But it is a ‘calling card’ with intention – to radicalise how images, and associations between them such as produce social cognitions like ‘a woman is a man’s plaything’ – become naturalised and accepted and thence oppressive to women including female artists. However, that needs more thought.

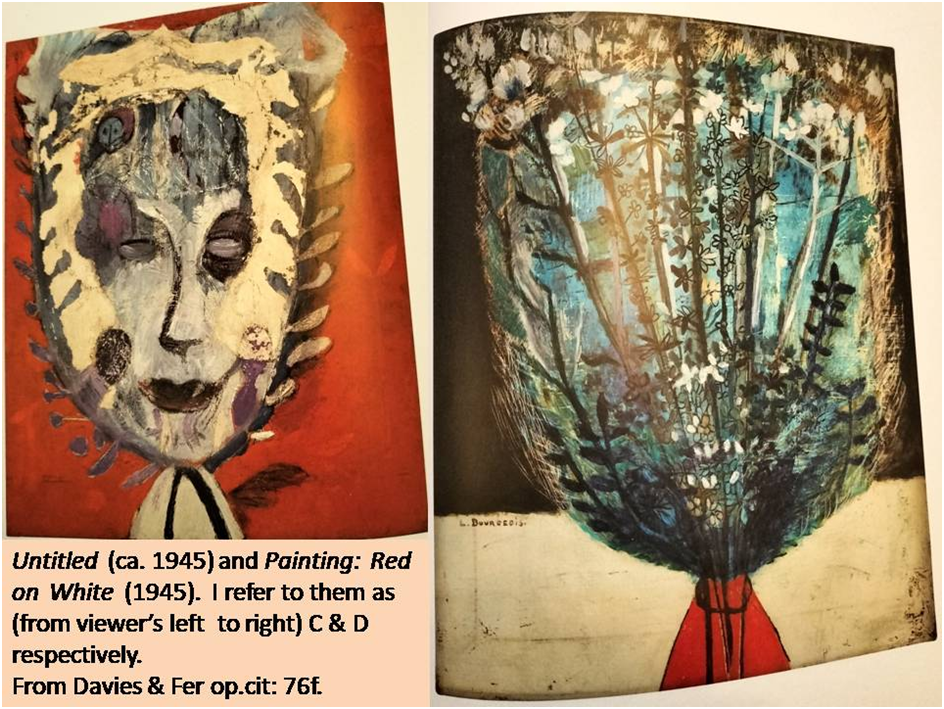

Other paintings radicalise imagery usually associated with women such as floral bouquets. The association is built in social practice wherein women become responsible for the beauty and decoration of the home, as well as more pagan associations with the flower whose beauty leeds to propagation of a species. This leads me to my favourite paintings paired in the book for this exhibition, from around 1945: Untitled and the more well-known Painting: Red on White. I reproduce them below and refer to them as (from viewer’s left to right) C & D respectively.

Fer describes D as the conflation of ‘a mask, a vase of flowers and a self-portrait’,[11] although the latter is difficult to justify visually, at least for me, although a perfect description of C, to which she does not apply it. Indeed C is a complex multiform self-portrait, containing a full face bust on the mask structure and full body figures. Including one (on the right cheek of the bust mask) resembling the stereotypical adult female icon, to which I refer in my discussion of Bilboquet above. A face is inset to the head of the bust mask but at its left cheek is the representation (as I see it) of a girl for whom the whole vision of femininity comprising the painting might be a predictive image of her future, including her death, since the shut eyes of the mask bust recalls a death mask.

These paintings then seem to refer to each other even as overlapping or reversed mirror images wherein the bouquet in D masks the faces underneath seen on C. The idea of a palimpsest seems important here – one effect of emotion, idea and associated image layering over another. The title refers to the contrastingly reversed uses of red and white paint between the paintings as foreground and figure (especially in relation at least of the base of the represented object (which may be a vase). I do not propose to find meaning here (although there is emotional effect where predominance of red creates more passionate affect in C). Instead I prefer to point to the representational issues it raises as based in questioning much like the girl’s questions of her destiny both as woman and as female artist. I feel like that often with Bourgeois. We cannot relate to single meanings or even emotions in relation to any topic. This is particularly so if the topic is understanding femininity as one woman experienced it, even a very unique one like Bourgeois; continually veering between the ideas and fears of a girl as she tries to live the life of a woman layered over it.

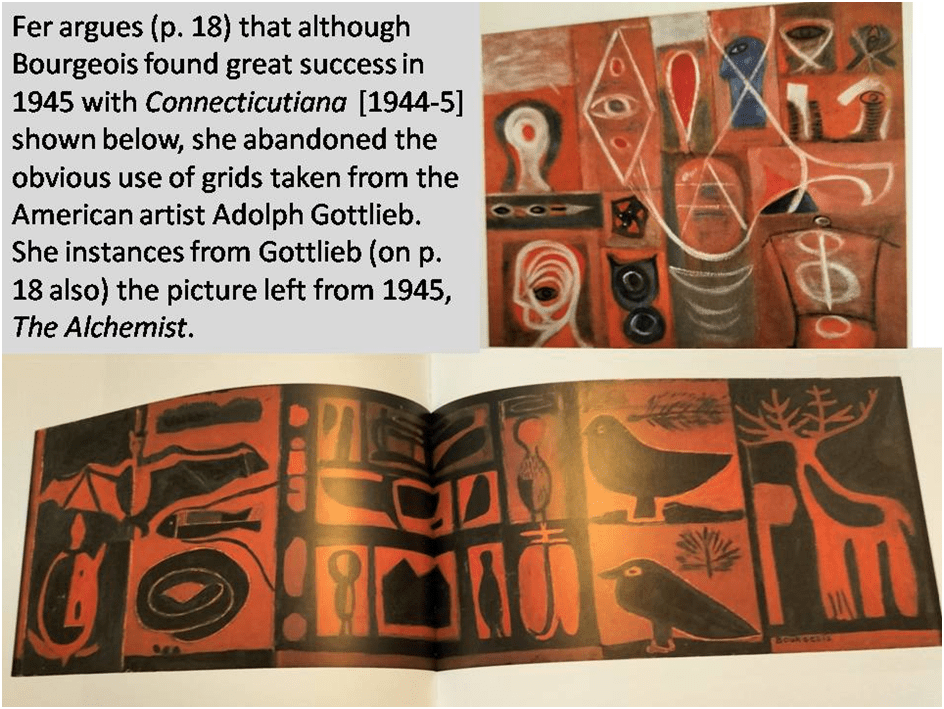

Some of this effect is explained by Fer in ways (which seem totally right to me) of seeing Bourgeois as attempting to knit together a theory of representation that worked for a French female émigré when the traditions that were emerging were either brash male theories from Europe in the form of a doctrinaire Surrealism and the male search for newer forms of iconology, even if they looked back to much earlier traditions, in Abstract Expressionism, such as Pollock’s interest in Native American imagery. In Abstract Expressionism that search was associated with frameworks drawn upon the painting’s surface. Fer brilliantly shows that Bourgeois rejected more schematic forms of the grid such as those displayed by Baziotes and Gottlieb but her paintings show that she still looked to the freedoms of experiment they offered to her. Compare for instance:

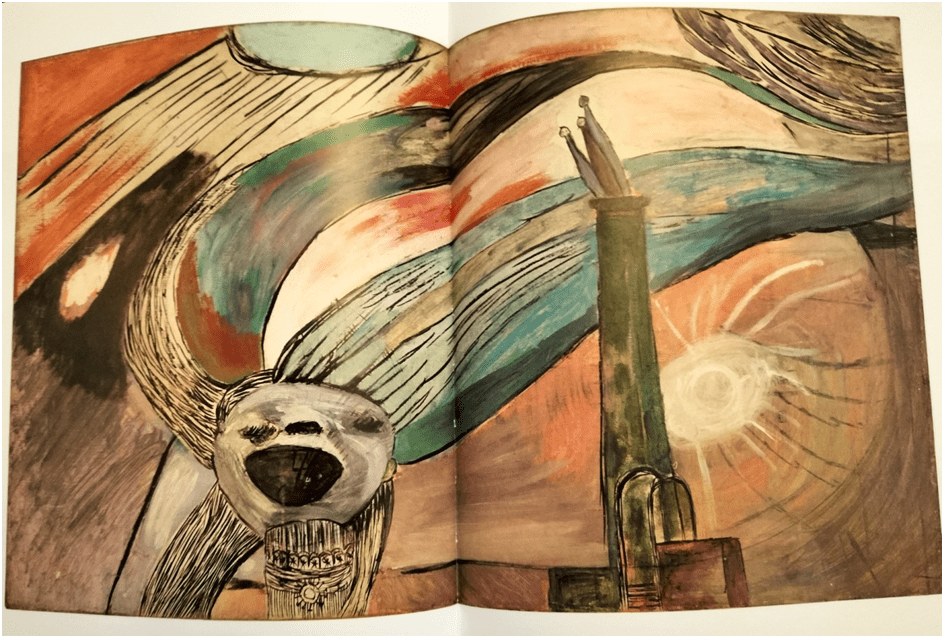

Instead she moved forward with less obvious plays with the surface – depth paradigm that had first produced the fashion for grids, because it accepted the flatness of the painting canvas. She moved I think into using washes of layered colour and passion playing around figures painted with a kind of abstraction such as he had shown in Red Night. The best of these being that featured on the cover of this book (Untitled 1946-7 p. 108f.) where figures and background are difficult to separate and in that sense abstract but integral to complex nuances of emotion, thought and sensation, which I am not going even to try to unpick.

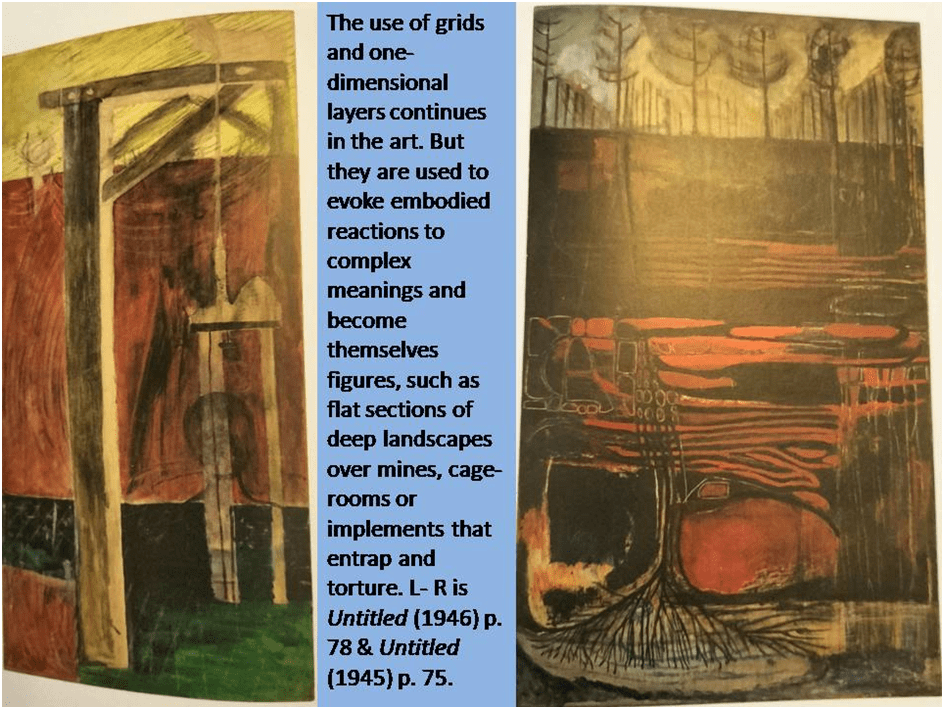

Such pictures did not mean the end of her use of grids and one dimensional layers however. Rather they are put to use to evoke a very embodied reaction to complex meanings and become themselves figures, such as flat sections of deep landscapes over mines, courtyarded houses or tenements, flats and large mansions or implements that entrap and torture. We are looking out to the later sculpture but we do not need that to fully appreciate some wonderful paintings such as those exampled below.

It is difficult for me to say how wonderful I feel is the second of these examples which ‘mines’ (quite literally) depth out of surface grids and layers (patterns of horizontal and vertical lines) making it meaningful, emotional and beautiful. These frames entrap whilst creating openness. We see this in the first example by her use of an intriguing and an obvious palimpsest wherein a ghostly figure is super-imposed above the inner guillotine like frame but perhaps also trapped behind the first and larger frame. I find it more than compelling. We are back from here to the Femme Maison paintings, which are so much more than feminist statements, though they are that as well in a very significant way, especially in an age like ours when the gender-critical can pretend to a very unnuanced ‘radical feminism’, as if the purpose of the movement was to rob women of the right to critical intelligence in the name of an identity label. Entrapments and openness in architecture are central In the Femme Maison paintings in their exploration of femininity and Fer links to major icons in the paintings, which should be rad after looking at these examples from the present exhibition:

A neoclassical courthouse, a clapboard barn, and a New York brownstone form a parade of historical building types that act as straitjackets for the femal figures.’[12]

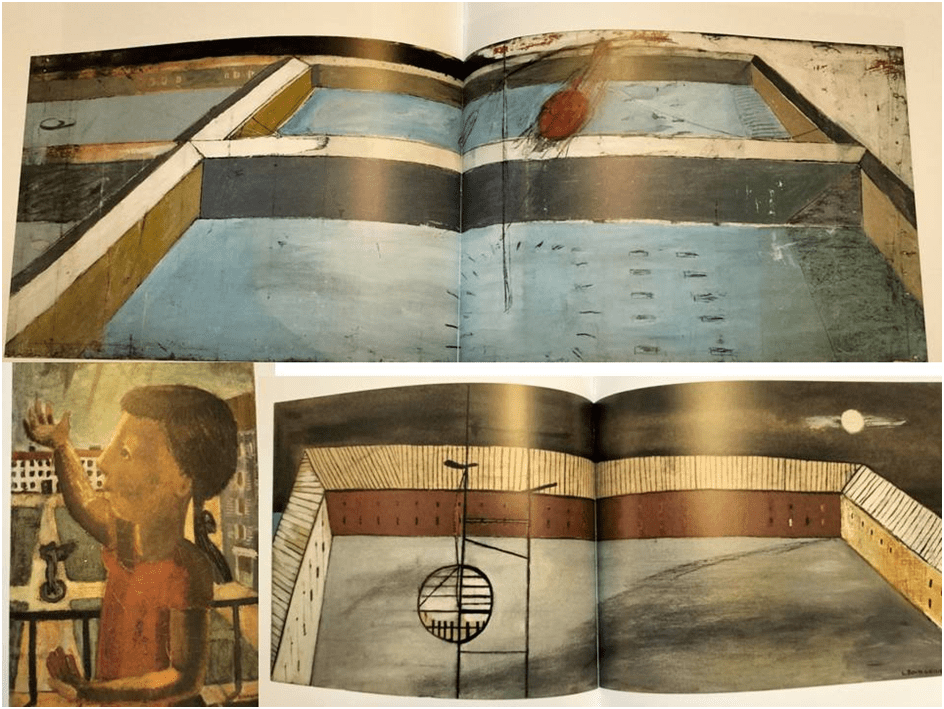

Surely these are grids too that rather than emphasise that painting is unable to escape the surface on which it is in reality painted, reasserts the import of depth perspectives so common in Renaissance art, of which Bourgeois made a ‘scholarly exploration’ according to Clare Davies. Such exploration enables an artist to acknowledge that in painting depth is a kind of surface, and perhaps vice-versa. Indeed an interview with Clare Davies in one review of the show marks the interest Bourgeois was showing at the time in Renaissance treatments of space:

These depictions of homes and buildings belie (sic.) Bourgeois’s early interest in physical spaces. … / “I found that she was going to the met’s Prints and draeings department often and looking at treatises on renaissance perspective on architectural drawings from the Renaissance,” said Davies. “She was really interested in how people were imagining space on canvas”.[13]

Even in 1939 Bourgeois envisages herself as a young girl feeling the rain outside from a balcony with a protective but imprisoning railway, in a grid courtyard that entraps artforms – such as (I take it) female angels – but also exposes them. The latter are described by Fer as ‘eerie, empty spaces – one solid, one watery – surrounded by blank facades that could represent a museum but are more like a prison or barracks, showing the perverse and brutal grip of imaginary classical architecture’.[14]

So far as it goes, this is a good description by Fer but it fails to note (here at least) that the chief aim is to query representation of the process of the developing cognitions, social practices and emotions of female life and its expectations. What strikes us in both, if in very different ways, is the play between abstraction and figuration that has to be encountered as we query each mark on the surface of the painting as a whole, especially that globule of bloody matter suspended over the watery courtyard in Untitled but also the semi-geometric abstraction that traverses the height of Regrettable Incident. We may try to see either as an object in the imagined landscape but are foiled even in the beginning of such an attempt. What we have here then is an art that faces the uncertainties of processes that cannot be explained by simple ideologies of identity – either of person or aesthetic profession – but must force each viewer to experience the uncertainties for themselves. It is only thus I believe that we will escape oppressions based in the need of security; for we need to know why those ideologies feel to serve a positive as well as a negative purpose.

Talking about Bourgeois is an obsession to those who confront her genius over time and learn from it – which is how I see myself these days. This book is a must-have for a true Bourgeois fan but will hearten anyone interested in art or the psychosocial-politics of representation. It makes you long to see the exhibition in person. That is the condition I am in myself, but the book helps. It really does!

All the best

Steve

Other Bourgeois blogs by Steve are:

Tate Liverpool Artists Rooms exhibition 2021

Hayward Gallery South Bank London ‘The Woven Child’ visited 2022FINAL LONDON ART BLOG (5): ‘If I’m in a positive mood I’m interested in joining. If I’m in a negative mood I will cut things’. This blog is really a love song to the art of Louise Bourgeois, so brilliantly curated for the current Hayward Gallery exhibition ‘Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child’ and the beautiful and brilliant accompanying book edited by Ralph Rugoff. – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

[1] Briony Fer (2022: 31) ‘A Decade of Painting’ in Clare Davies & Briony Fer (Eds.) Louise Bourgeois: Paintings New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art with Yale University Press, 13-31.

2 Clare Davis (2022: 9) ‘Introduction: A Visual Lexicon of Displacement’ in Clare Davies & Briony Fer (Eds.) Louise Bourgeois: Paintings New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art with Yale University Press, 9-11.

[3] Briony Fer, op.cit: 31.

[4] Ibid: 27

[5] Deborah Menaker Rothschild (1991:163 & 166 –latter for Futurist model) Picasso’s “Parade”: From street to stage London, Sotheby’s Publications with The Drawing Center, New York. And ArtPlastoc blog (2014) ‘249-PICASSO AND THE BALLET “PARADE”, 1917’ Available at: https://artplastoc.blogspot.com/2014/09/246-picasso-et-le-ballet-parade-1917.html

[6] Deborah Wye (2022) on Louise Bourgeois. Femme Maison. 1946-1947 Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) in New York. Available at https://www.moma.org/audio/playlist/42/665

[7] Untitled ca. 1948 in ibid: 131

[8] Shanti Escalante-De Mattei’s (2022) review of this exhibition in Art News [May 23, 2022 3:26pm]available at: https://www.artnews.com/art-news/artists/louise-bourgeois-paintings-met-1234629154/#!

[9] Fer op.cit: 21

[10] Davie & Fer (Eds.) op.cit: note 13, p. 158.

[11] Fer op.cit: 27

[12] Ibid: 28

[13] Cited Shanti Escalante-De Mattei op.cit.

[14] Ibid: 29

7 thoughts on “Briony Fer says Louise Bourgeois abandoned painting when painting itself abandoned the representation of an external world and its phenomena in the view that ‘the most ambitious art had to be abstract and obey certain pictorial protocols – an opinion that, with all such doxa, was fundamentally exclusionary and to which she never adhered’. This is a blog on Clare Davies & Briony Fer (2022) ‘Louise Bourgeois: Paintings’”