Recommending Paul Deslandes (2022) The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain: From the First Photographs to David Beckham Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press.

I love this book. But I decided that I didn’t want to discuss its ideas because the whole concept of pursuing (as is the way of the academic) one idea– that of an aesthetic of male beauty as the main focus of historical change in a long and complex period of many interacting psychosocial changes through history does not in itself interest me enough. As I wrote, I kept going off at tangents in trying to build my own argument around it. Suffice to say it is a very good book, highly readable and entertaining despite the academic conventions it uses of summarising everything at the beginning and end of chapters.

I still quibble over a small but important point about the too exclusive (in my view) definition of intersectionality as a concept but, on the whole, but it is a book that never needs reminding that our sense of personal identity is complex and far from determining in regard to any one label of psychosocial and psychosexual identity. Its conclusion is, simplified of course in such a rich book, that the whole history of male beauty in the period leads us to something like the situation Deslandes describes in the 1990s and early 2000s In Britain. He says that for ‘British men in this period masculinity was an experience lived though their bodies as a kind of aesthetic space, as physical entities that could be adorned, sculpted and clothed’.[1] One outcome of this, and other changes of course, was the destabilising of concepts which had in the immediately preceding centuries been relatively stabilised as binary concepts of masculinity and femininity on the one hand and queer and normative on the other. This conclusion is entirely to my taste and I agree entirely. In the space of this argument he skips between different instances of culture from the (to use a term from the 1950s description of culture) highbrow to the lowbrow. The latter includes fashion in clothes, hair and physical maintenance of the body as well as published material that was not intended to last and hasn’t, like the ‘gay’ magazine Zipper.

For my purposes the complexity of the term intersectionality is related to the fact that most of us have experience of oppression and an ability to oppress as a result of how we are identified, even prior to our own action in the world. That is clear in its discussion of the radical image-making of the British Nigerian photographer, Rotimi Fani-Koyode because his work is aimed at reflecting on the politics of marginalisation, desire and objectification in images of the beauty of queer black men and how that reflects on how men generally experience the beauty of another male. Experiencing beauty does not feel as if it is something in which interpersonal power dynamics play a part but we read carelessly if we don’t notice Deslandes showing us that, in fact, it does do so in his descriptions of the cultural history of male beauty. Fani-Koyode’s images, for instance, are cited to show the complexity caused in inter-relational dynamics between the fact that black queer men experience oppression sometimes by white queer men, even if in subtle ways in some forms. For instance images of the black body can be psychologically objectified so that that body is seen as subjected to white male desire rather than having its own agency in a person.

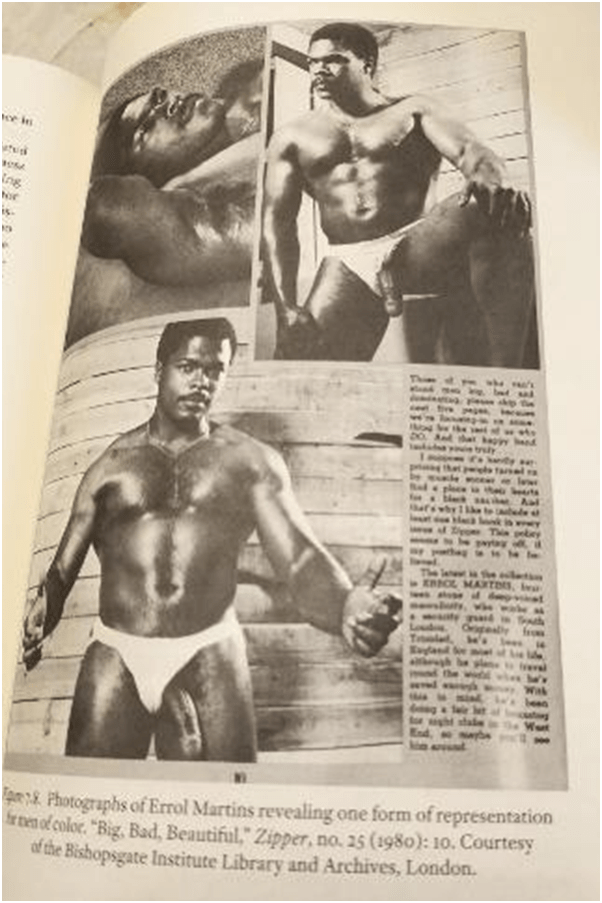

Moreover, images of black bodies, even as objects of desire, have also sometimes collapsed into hints that they represent the projected sense of danger and threat thought to correlate with a white queer male desire. Even when that sense of risk may in itself stoke further desire, it marginalises black consciousness to what the black body means to white men, not what it means to the black person themselves. The best instance in the book comes from 1980 where the gay male magazine Zipper featured Errol Martins, a South London security guard who modelled for the gay male magazine Zipper, with a largely white audience and creative staff, under the label ‘Big, Bad, Beautiful’. Errol is characterised by ‘deep-voiced masculinity’. Nothing is left to the imagination about what kind of ‘bigness’ is intended in this label for Errol’s penis hangs down from white underpants. Errol is not naked (because of course he is wearing underpants) but this fact emphasises even more that large penis.

Those who do not like men ‘big, bad and dominating’ are asked in the magazine to skip the 5 pages of photographs of Errol that follow.[2] The word ‘dominating’ leaves us with no doubt that Errol is objectified in a way that reduces him to an icon of the fearful, jealous and desirous elements of white male fantasy. In various ways we see this too in the photography of Robert Mapplethorpe of his black lovers but being American, he does not feature in this book. In passing it is worth noting however that during this period excluding the influence of the cultural influence of the USA on the concept of male beauty from the book merely because it focuses on Britain may be mistaken, but clearly no book could cover every influence in the development of one nation’s conceptual ideologies whether of ‘male beauty or anything else.

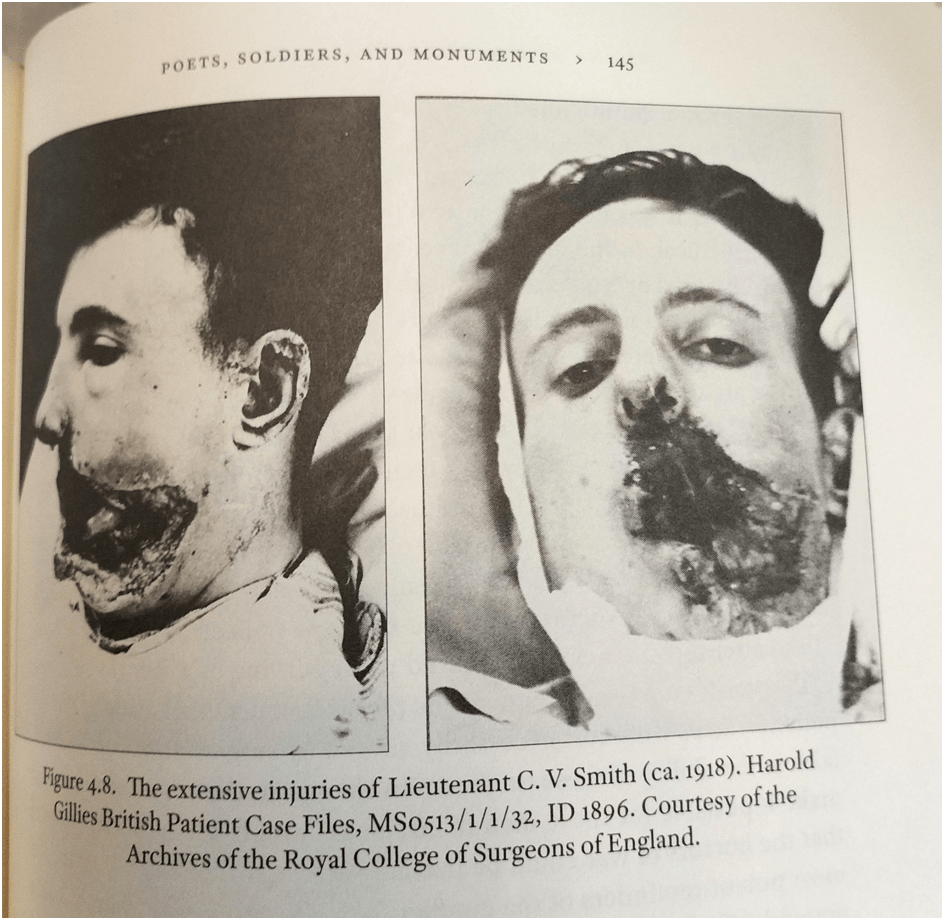

In another instance where the term intersectionality might have been used more carefully I think it matters a great deal for the book hinges on the development of discourses of male beauty in part set against the experience of disfigurement and its public exposure. The instances of the latter he analyses are the facial injuries of soldiers in the First World War, and in the early coverage of the AIDS pandemic as a ‘gay plague’ in the 1880s and 90s. In the latter case the aesthetic effects of certain symptoms were fore fronted in the popular mind by the national media and Deslandes sees in this a concerted effect by the communities involved, in particular, to assert ‘physical fitness and the absence of muscle’.[3] Deslandes is aware I think that these instances of ‘disfigurement’ reacted against objectify men whose subjective take on these circumstances he feels he need not cover in his book, though he voices his respect for them early in the book.

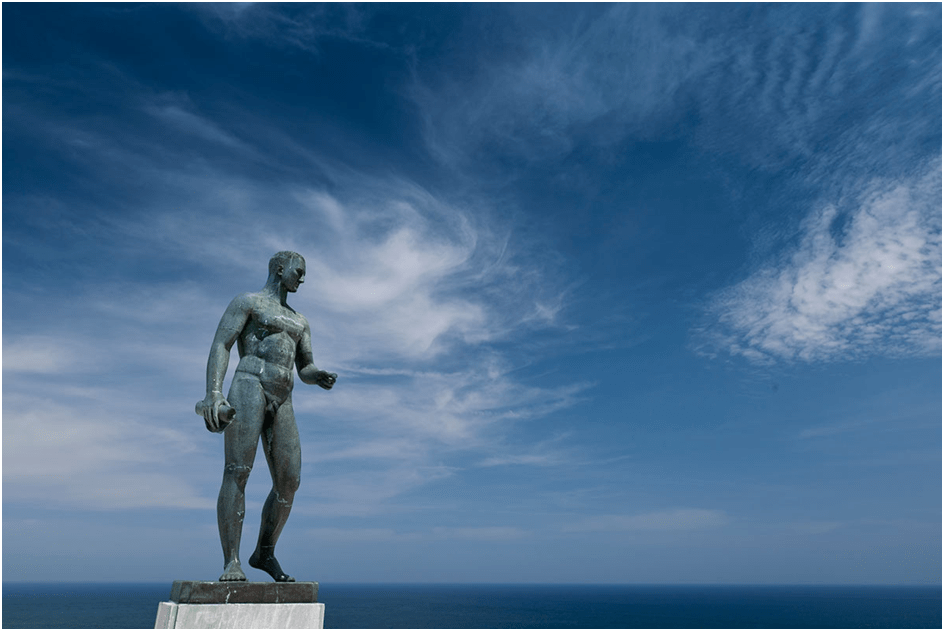

In the instance of World War I he instances the huge use of personal photographs to emphasise the wholeness of body and lack of facial disfigurement that occurred throughout the range of social classes and in which serving soldiers were active agents. Serving soldiers sent pictures ‘home’ to accompany letters written to family or lovers as reassurance of their look. However, these photographs were also used as exhibits in public places like shop windows or in memorial cards that showed men in an aesthetically pleasing way to mitigate the effects of their death by emphasising their lost youthful good looks.[4] In the realm of the ideological use of male body imagery, Deslandes also uses these effects of war to explain the need for a symbol of fresh male beauty such that social leaders, including Winston Churchill, promoted a focus upon the beauty of the soldier-poet, Rupert Brooke. This was commemorated in relief-busts (at Rugby school for instance), photography and a nude statue of ‘immortal poetry’ (but often mistaken as a representation of the man himself) in Skyros.[5]

However, my own interest in this book focused on its central use of imagery from the queer artist Keith Vaughan and this focus shows both strengths and weaknesses of the book.[6] I cannot question the summary that I quote immediately below from Deslandes. As a statement it is even relatively novel in that it shows how the aesthetic moment complemented psychosocial discourse about the aetiology of ‘homosexuality’ in the exclusive male homosocial opportunities offered by social groupings that were not explicitly sexual. This enabled an iconography that ‘both camouflaged and revealed’ the homoerotic potential therein.

Drawing … on the familiar theme of bathing, many of these paintings reference the seaside as a site of homosocial bonding and erotic potential. Yet the eroticism is both oblique and direct. While faces and penises may be abstracted beyond recognition, buttocks feature prominently in marking muscular and erotic potential, … . … depicting men dressing and showering or in relaxed poses … Vaughan’s use of groups in much of this work and the suggested sexual opportunity associated with washing, toweling (sic.), and touching hinted at both the possibilities of looking at beautiful men during the war and important same-sex urban pleasures embodied in the form of Turkish bath-houses … .[7]

I think this statement considerably simplifies the instances of the homosocial, for I do not think the bath-houses need at all to be invoked, especially in the class situation of Vaughan’s early life pre-war and during the war. This life differs immensely from the bohemian class represented by, say, Christopher Wood, of which this would be more precise (see my blog on Wood and bath-houses). Although haunted by the personal beauty of men, as recorded in his tremendously frank diaries, I do not think that this argues merely for a visual aestheticisation of male groups. The touching he describes in these pictures is not only incidental but, in desire at least, purposive, as might be gathered by a drawing he published in John Lehmann’s Penguin New Writing, which uses a male sexual embrace to imagine an apocalypse in London whose destructiveness might bear new and creative psychosocial truth. It is a work clearly influenced by William Blake. Here is a piece (corrected slightly) from a draft of my unfinished MA dissertation for which the Open University could not find a sympathetic supervisor (crucial these people since they mark it). I note how in diary writings:

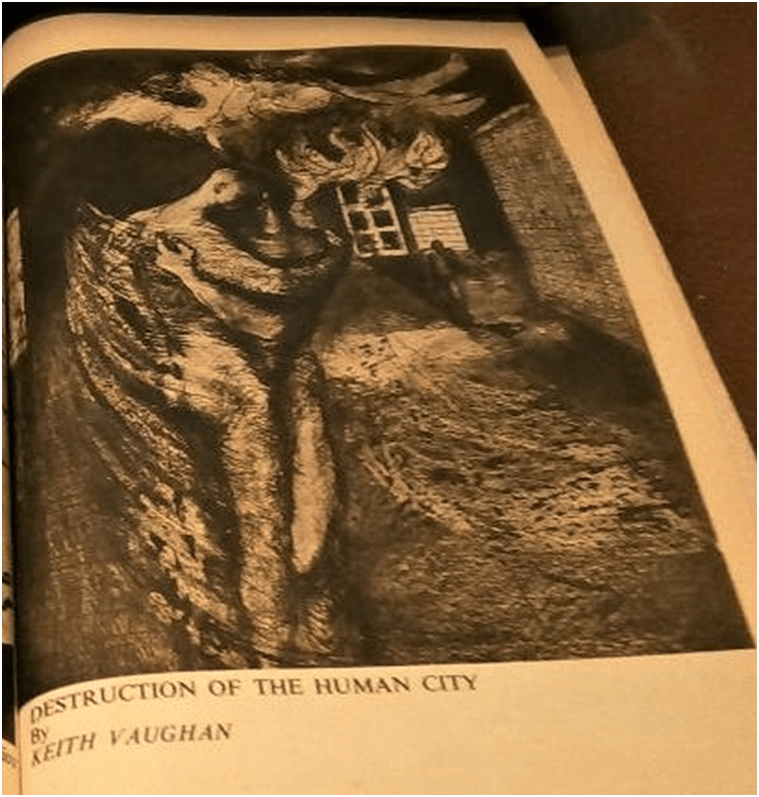

… class and social divisions are characterised as aspects of parting and division, intimacies as of coming together. These are very much the way in which gay men thought of the coincidences of the war – of accidental intense meetings and early partings and of a relatively psychosexually freer society. In an essay in Penguin New Writing ‘War Artists’ in 1943, Vaughan wistfully wonders whether art might, under government dictate, be tied to the state as guiding artists known as ‘Official Artists of The Reconstruction’ just as Sutherland was an Official War Artist: ‘The field could be extended to cover every aspect of social life’. Referring then to the ‘vision in ruins’ photogravure set in that volume, it is clear that one aspect of reconstructed social life might include queer assembly. His ‘Destruction of the Human City’ (recalling the city left by Christian in The Pilgrim’s Progress for his journey to the Celestial City but also countless iconic paintings of the Biblical Sodom) men hold each other in loving and naked embrace surrounded by symbols that connote both destruction by fire and natural regeneration, as in Blake.[8]

Moreover, the sense of validating eroticism emergent from the homosocial is in Vaughan something very different from the specialised homosociality of say the Jermyn Street Bath House, for the latter is already an eroticised situation as Christopher Wood’s painting of it makes crystal clear. This is not so of ‘ordinary’ gatherings of men – the subject of Vaughan’s assembly paintings. In my MA draft I tried to trace this to a 1942 gouache painting by Vaughan reporting his war-time experience known as Coal Fatigue.

This is what I wrote. I think it still valid.

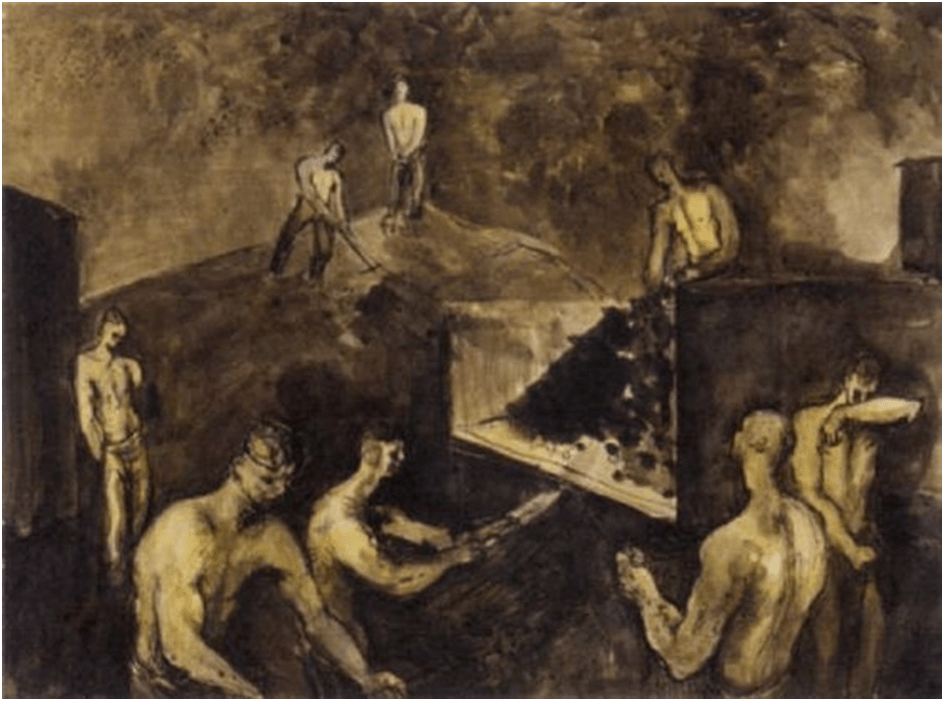

Coal Fatigue was made in 1942 and is seen by Hastings in a recent catalogue entry as explicated both by Vaughan’s empathy with working male groups, which he compares to that found in Moore’s and Sutherland’s wartime art, and by his experience in January 1941 in Regiment fatigues involving filling sacks of coal from delivery trucks. Hastings cites one instance from 20 January.[9] Although it might feel churlish to question the applicability of this citation by Hastings, it is necessary if the real tensions of that wonderful gouache are not to be missed. The text refers to a quite different task to that in Coal Fatigue, wherein men are not unloading but loading coal. Moreover although the term ‘fatigue’ is meant to refer to the bodily effect of ‘tiredness’, it does not show the effect of rain and cold. Moreover in the January reference it is winter and the men are so fully clothed that they feel, ‘black slush working its way up the inside of (their) sleeves’.[10]

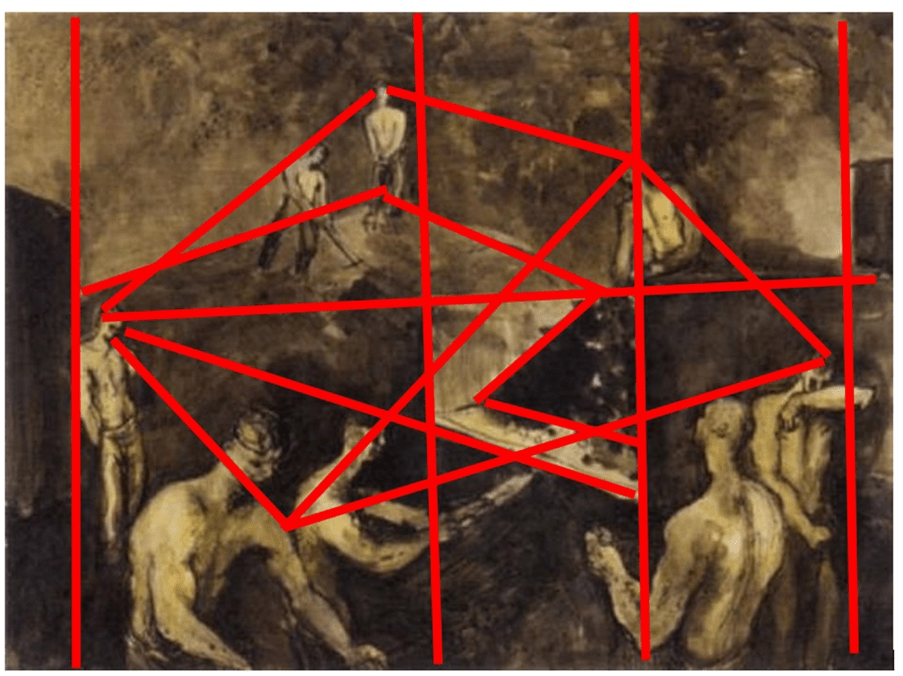

In contrast Coal Fatigue emphasises not cold and wet but warmth, even gruelling heat and this justifies the semi-nakedness of the group in very literal ways. Missing this leads Hastings to emphasise the ‘dreariness’ that links picture and textual extract. However, the effect of looking at this gouache cannot be reduced to ‘dreariness’ of the work it pictures. Hastings himself points to the use of formal means to emphasise the isolated watching figure on the picture’s left but again leaves us with a sense (of an interest in isolated absorption) that does not exist without other contradictory effects. Even if we take the formal lines, constituted by the straight extendable lines from the back of the truck which extend to the isolated onlooker, they do not contribute a full argument awareness of the compositional features of the painting unless we see these lines themselves as part of a much fuller set of lines containing other regular shapes that help compose the figures and objects (building walls, vehicles, loose coal) in painting as a group. In effect negative feelings of isolation and mutual separation are in full tension in this set up with the social affect that we might call group-feeling. And it is this which becomes central to Vaughan’s notion of ‘assembly’ in his later work. And it is this pleasurable patterning of the assembly of naked torsos which begins to make even his early art ‘bear a certain relation to gayness’. The torso are however patterned within a landscaped setting which convey affects of the relationship between its figures – affects which arise from the active performance across these spaces and between those torsos which are alive with the life of the varied media as handled and performed by the artist.[11]

My take on Vaughan is not here however to divert us from Deslandes’ book but to point to where it emphasises merely observing the visual beauty of companies of men over more performative senses of male bonding in groups in which Vaughan sees some hope, not just of sexual play which he definitely did, but of transformation of social and ethical mores wherein sin lay in isolation not sociality. Deslandes quotes things from Vaughan that say the same I think as what I do in the sentence preceding this but he constantly over-interprets these words to meet the academic thesis he is promoting, which concerns the central importance in the period appreciating male visual beauty from a distance and in a frame of vision alone as it were, in a manner akin to Henry Scott Tuke. For instance note how Deslandes keeps interpreting Vaughan’s prose such that it maintains his argument within a frame of reference of the effects of visual beauty.

During his time as a Saint John’s Ambulance brigade volunteer in Guilford, he recorded several scenes that highlight the pleasure derived from observations of male homosociality on display.

Yet what he then quotes (though interpreting it merely as turning from the visual to discerning an opportunity for sex) is about a richer sense of Vaughan imagining companionship with men that addresses both his isolation and the ‘ethical’ frigidity of his culture. While isolation is seen as masturbatory and hotly and rigidly stiff like guilty self-play, the play of men together is seen as pervaded by the healthily hygienic fluidity which cleanses animal ‘lust’. I insist that is that this prose is not just about appreciating beauty VISUALLY. Even the use of ‘sic’ here is an attempt to persuade us that Vaughan has made a spelling error (‘loose’ for ‘lose’) where the language actually needs us to know that losing a rigid self is similar to ‘loosening’ the hold on oneself

“I wanted to loose [sic] myself in their careless animality to soak and drown my too dry sense with heavy lust. I was stiff and hot when I turned into the door and they went on shouting into the clean night”.[12]

Moreover, this is not, I would insist, just about sex. For explanations of the genesis of homosexuality in the period made a great deal of the danger of groups of men acting together without the presence or goal of female company. Indeed this was a large part of my proposed MA dissertation but less of that. I merely here want to show a possible limitation of this book’s academic rigour and focus on one isolated argument about cultural change – a pervading problem in academic training.

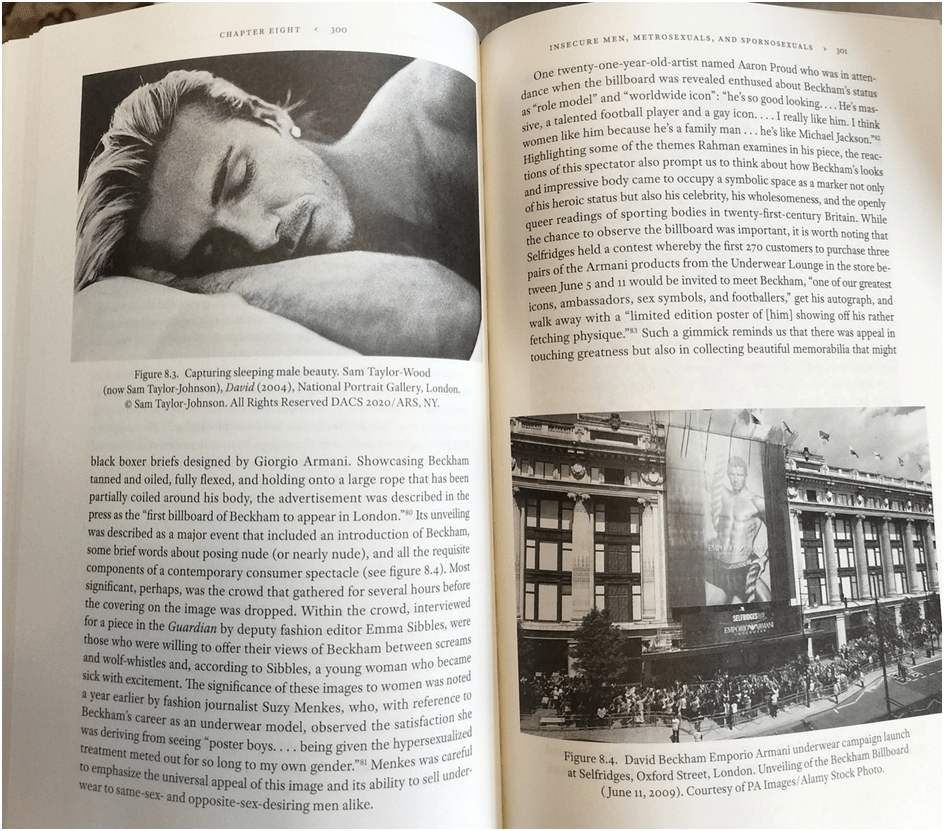

But do read this book for what it is, even in its limitation. For instance, read it for its build up to an understanding Sam Taylor-Wood’s wonderful film portrait of David Beckham. In short, it is excellent as a limited thesis on a subject that has more to do with visual culture cut off from any meaningfully comprehensive context in the history of masculinity as a whole. For despite its stress on the beauty of the male body, it is too obsessed by the visual and untouched, as much as it should be, by the haptic in art and social life and the loosening of boundaries into new forms of social grouping in process through history.

This is a rambling look at a book I liked a lot. Do read and share your thought if you will.

All the best and queer love

Steve

[1] Paul Deslandes (2022: 319) The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain: From the First Photographs to David Beckham Chicago & London, The University of Chicago Press

[2] Ibid: 270f.

[3] Ibid: 280

[4][4] Ibid: 135f.

[5] Ibid: 150ff.

[6] See ibid 197 – 204.

[7] Ibid 199f.

[8] Quotation from my preserved draft of MA dissertation with minor corrections. I have deliberately refrained from making academic reference to sources to emphasise the fact that this was merely a first draft

[9] Vaughan (1966:42) in Hastings (2019:50)

[10] Ibid.

[11] Quotation from my preserved draft of MA dissertation with minor corrections. I have deliberately refrained from making academic reference (or adding to ones I did then create) to sources to emphasise the fact that this was merely a first draft

[12] Quotation [and citation from Vaughan’s diaries] in Deslandes op.cit: 203

One thought on “Recommending Paul Deslandes (2022) ‘The Culture of Male Beauty in Britain: From the First Photographs to David Beckham’.”