‘ “… You should be in three places at once, and I loathe having to wait my turn.” …, George expressed in concrete terms the complexities of their multi-level polyamory’.[1] This blog reflects on imaging queer lives and interactions in the light of the concept of polyamory. The blog uses as its case study, Allen Ellenzweig’s (2021) George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye New York, Oxford University Press

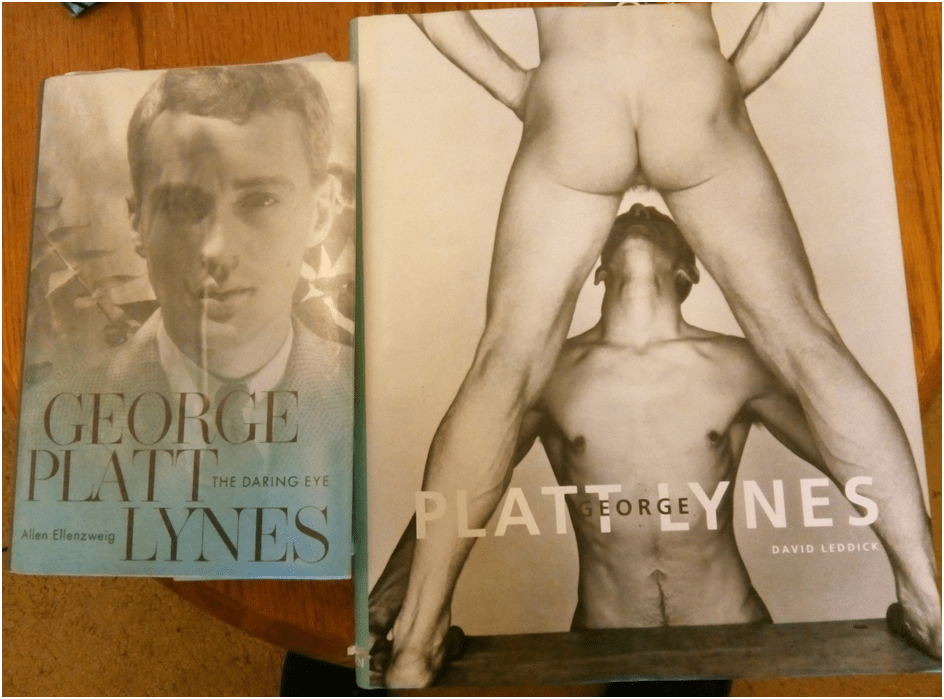

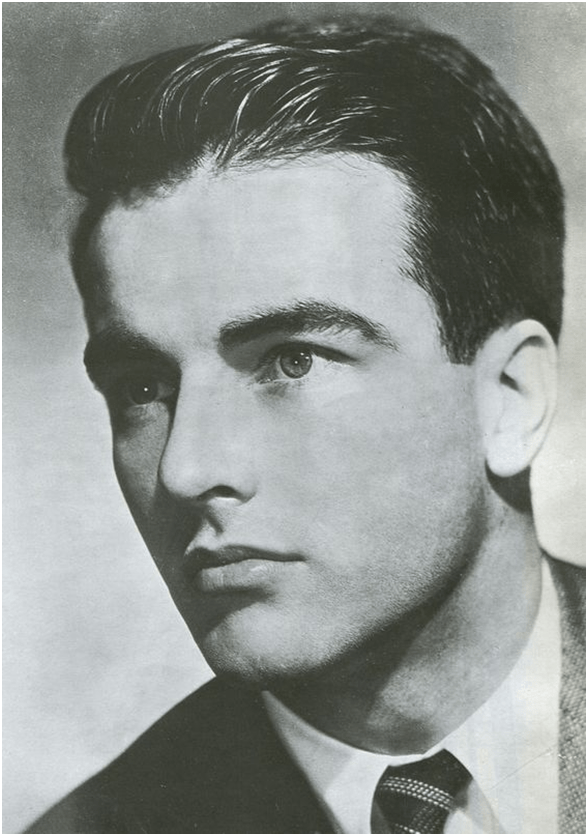

This book situates George Platt Lynes’ career as an artist and photographer in the middle of changes in the Transatlantic consciousness about sexuality. To these changes it is addressed as the object of artistic and aesthetic exploration and as a social movement of a distinct group of white middle-class American men. It has to said, though, that in terms of social awareness at least Platt Lynes veered more to an interest in the aesthetic than the socio-political. In his consciousness of male–to-male sexual attractions however there was more than just aesthetics involved in Platt Lynes attitude. It is just that this ‘more’ was not expressed in terms of a politics of the psychosocial construction of the personal but of a social zeitgeist. His involvement with Dr. Alfred Kinsey for instance had more to do with the latter’s appreciation of the value of his photographs of male nudes ‘not merely as aesthetic objects, but as a confirmation of beauty as part of the life force’.[2]

I might have preferred some sense of how and why Ellenzweig here uses this phrase about the ‘life force’, which puts sexual politics in the realm of influence of Nietzsche rather than Marx or Engels because such ideas were extant in the period still – lingering on in George Bernard Shaw and raging in D.H. Lawrence. In a lesser form I think both had a short-term influence on America in the early days of Tennessee Williams and Donald Windham, at least in the play You Touched Me!, first performed in 1945 for instance and based on a Lawrence short story, which sometimes reads as if inspired by Shaw’s Man and Superman. Here is the beautiful hero, Hadrian (first played by the young Montgomery Clift):

HADRIAN: The future knows the good things in the past. … Such things as music – poetry – and gentleness, Matilda!

…

HADRIAN: … The future is only fierce for a while so that after time it can be afford to be gentle. Much more gentle than the wrong, deceitful past of the world could be – … There’s struggle ahead. …. …in the end it won’t be possible for even the most determined sitters-out to keep the gentleness in them. They’ll lose all they want – to the ones that resist our progress.[3]

The sheer force of male beauty and sexual potency is homophobic and heteronormative (to say the least), at the level if social campaign, in Shaw and Lawrence but not in its adoption in the USA. And in transatlantic terms the issue is merely aesthetic because it is about a Renaissance in the evaluation of male beauty in its own terms, rather than as a complement to feminine beauty. In the hands of Paul Cadmus, the Renaissance was of figurative art focusing on contemporary Princes of men (and a few sailors), down to the use of egg tempera.

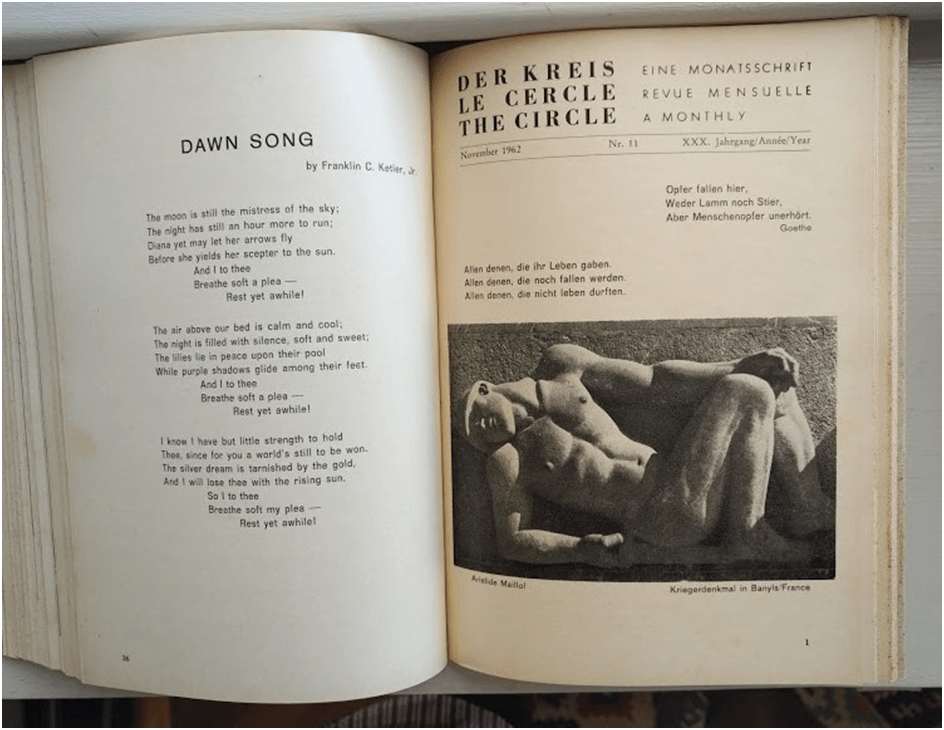

Ellenzweig shows a possible maintaining force of this idea in the 1950s in the Transatlantic queer campaigner, Karl Meier (who was known as ‘Rolf’). The latter edited a ‘Swiss homophile monthly’ called Der Kreis (The Circle) and wrote of nude works he commissioned from Platt Lynes as being the work of an artist, ‘who has comprehended and grasped the magic and beauty of the well-formed male body: who has formed the ineffable of male Eros with the secret of light, with pictures composed down to the last thought-out detail’.[4] The secret of these works and their appeal was the idea of groups of naked men ‘in smiling direct contact with each other’. In that sense they may recall the work of Keith Vaughan in the UK too as well as Paul Cadmus in the USA.

Hence, although this may not be a political social movement, such as that envisaged in better known and later prototypes Der Kreis was, according to Jonathan Weinberg (cited by Ellenzweig) a shorthand for their preferred circles ‘of fellow artists and patrons who shared their attraction to men’. It was ‘created to summon such communities into being and to sustain them’.[5] It is a very different kind of ‘gay movement’ we are looking at here then, which exalted in the power of queer circles of wholesome male lovers of men united in this dynamic rather than any ‘social identity’ (a much later invention) than that which united wider social groups in later queer history.

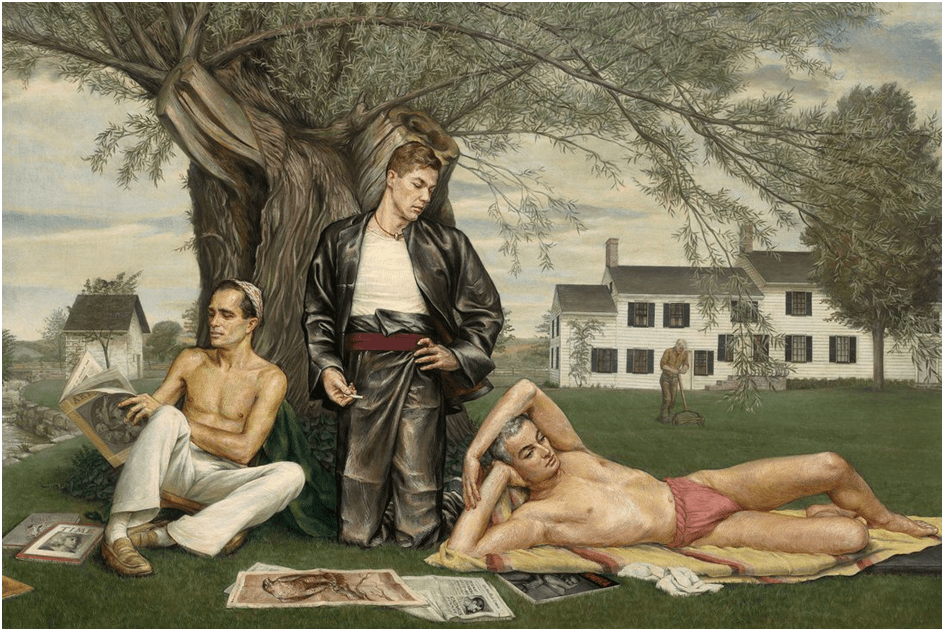

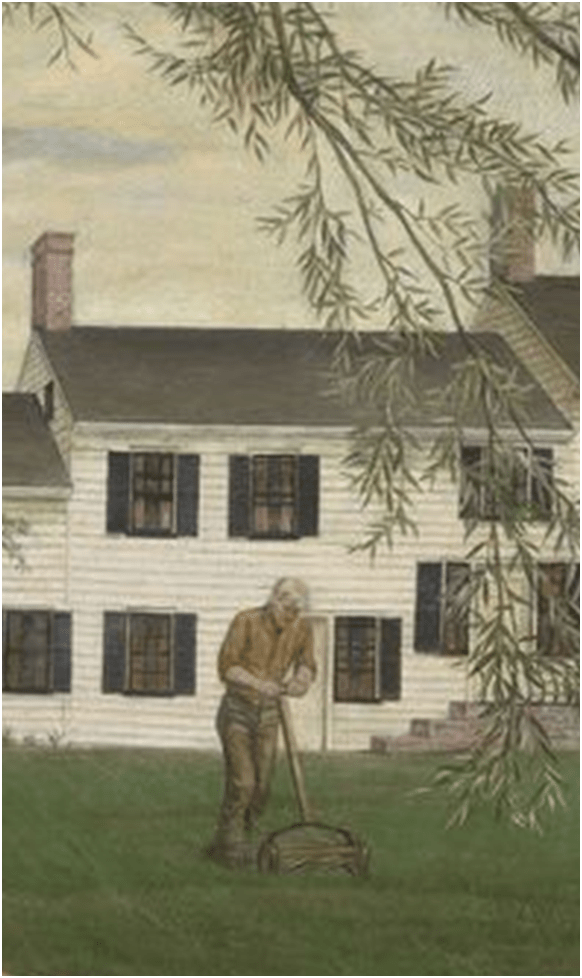

In this blog I want to explore why a group of queer men in the USA were to envisage lives, independent of political change at a structural level, embraced instead the use of their current social power (for these men were relatively well provided for) as artists and art-collaborators to change the way people responded to bodies and their beauty, not least their associated symbolic sexual potency. They did this in loving networks (that were sometimes not so loving: indeed they could be compacted and blocked with jealousies and the fear of rejection). Though the quotation in the title references to a four-pointed relationship containing three men and one woman, it is true to say that the woman, Barbara Harrison, was only part of the group at that time since one member of the ‘throuple’ of men, Monroe Wheeler, was consistently attracted to women even though these sexual liaisons were short-lived comparatively. This is one of the most celebrated throuples of this period and celebrated by members in the wider network, notably the monstrously talented and ironically aware painter, Paul Cadmus. He painted the throuple outside their common house (for a certain period) Stone Blossom. It is worth looking at this painting now in order to talk more about the period before and after that it commemorated. Its ironies are important too.

Ellenzweig tells the story of the making of this painting which portrays, from the viewer’s left to right, Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Westcott and George Platt Lynes ‘who, stripped to a brief bathing suit, displays himself like an Odalisque, … Glenway’s glance is poised downward to take in the full measure of George’s nearly nude spectacle’.[6] Ellenzweig makes much of the dismembered tree with two ‘severed’ branch stumps which he sees as a ‘disquieting signal’ of the relationship’s potential fracture lines. I have already blogged on Glenway Westcott’s intriguing novella, Priapus, (blog available at this link) which maybe gives a clue to a more specific and here humorously treated fracture point.

For Westcott felt that his abandonment, as he saw it from the sexual aspects of the threes cornered relationship was based on a rejection of him on the basis of his penis size (a point he shares in his Journals and Priapus) and the painting shows both men at the apex of this relationship’s triangle boasting obvious bulges in their groin area, whilst Glenway is holding the leather of his trousers flat to his body, the Baroque folds of his clothing betraying an ‘absence’ (apparently though Glenway’s obsession about penis size – in Dr. Kinsey’s view – was not justified by facts). Cadmus, wickedly funny as ever, pointedly emphasises the issue by the placing of Glenway’s hand pinched around the visibly small shaft of his angled cigarette, placed near his groin. I sense that this is the measuring up going on in Westcott’s gaze on George, who was famously well endowed, and I see it as comic rather than tragic in the manner of Ellenzweig’s ‘Cut is the branch’ motif.[7]

And indeed, it is difficult to see as tragic a relationship that endured the end of cohabitation and sex with each other for all three and still continues; one too where Westcott so often gave Monroe away to Platt Lynes’ sexual love in almost heroic acts of self-denial. I think it is almost impossible at this distance to make negative conclusions about polyamory as a mode of conducting relationships. Of course it conflicted with notions of fidelity, even polyfidelity as the recent craze is, in relationships but when George asks Monie (his name for Monroe Wheeler) to split himself three ways (in relation to Barbara, Westcott and himself) he was not at the same time ruling out multiple other physical but not primarily emotional relationships that any of the partners might also be having at the same time. Fidelity was a matter of ‘love’ whatever each meant by that alone not physical sex.

However, for me one other point remains regarding Cadmus’ Conversation Piece. In looking at it closely, another irony in the nature of the throuples’ life communicates. For cutting the huge lawn in the rear is the image of an older rather good-looking man clearly past the age of sexual tension and peacock display of the three central powerful figures. In my view, Cadmus is reminding these Renaissance princes that their power is entirely temporal and not forever, another great theme of the Italian Renaissance, which this neglected artist aped. That the temporal influence of this artistic trio will NOT endure is in fact the tragic flaw in the group we are considering, as I think Cadmus knew, and which, at some level, with the ups and downs of their careers and marginalisation well before their deaths was brought home to them far too cruelly. This was not only because beauty will not last but that neither will their reputation as leaders of modern art. This is not what they had expected as young men on the edges of a coterie in Paris including Gertrude Stein (who consistently called Platt Lynes to his chagrin understandably, ‘Little George’), Jean Cocteau, René Crevel, Eugene Berman, Pavel Tchelitchew, and André Gide. We have to bear this in mind when we confront what we might call the ‘genteel poverty’ that George Platt Lynes is forever drawing attention to in his late career as his style of photography – statuesque, theatrical and studio-bound, became too old-fashioned to sell in magazines or journals celebrating both everyday fashion and celebrity.

That we all grow old has the status of tragedy only when groups define their value in terms of endurance in glory, not merely endurance. George Platt Lynes declaring himself in August 1947 ‘poor, poorer than ever’ was an objection to having to let his an employee to organise his life and to have to rent his back bedroom to a an ice cream parlour impresario, and even ask his current boyfriend (with the irresistible name “Randy” (unfortunately just an abbreviation of Randolph) Jack to share expenses on his flat.[8] Even in later bankruptcy Platt Lynes crested the waves his brother’s support.

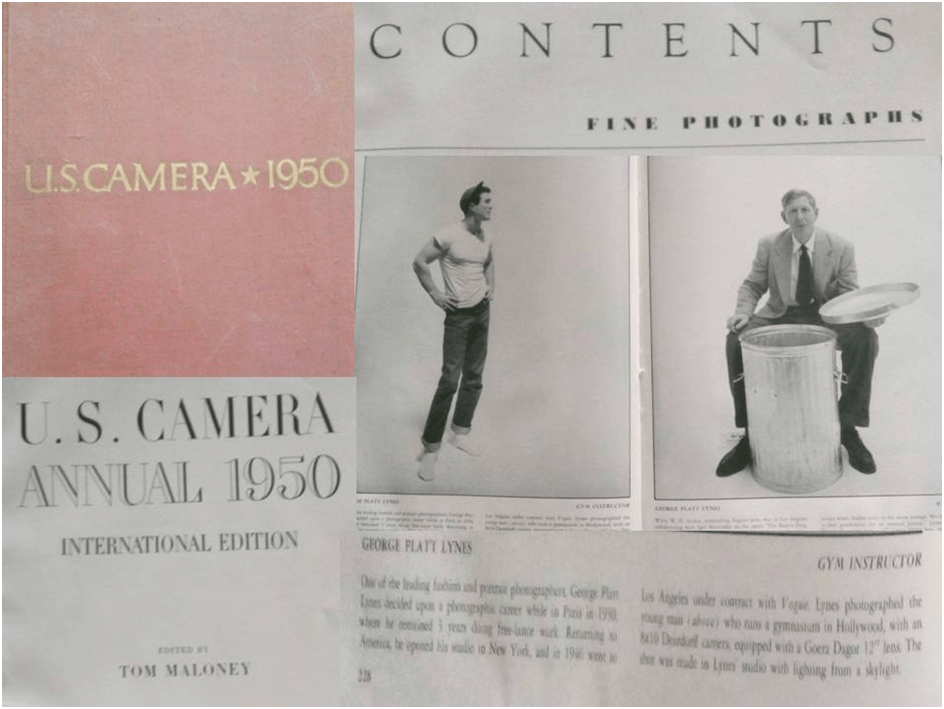

In 1950 however his photographs were still collected in the International Edition of Camera USA as ‘Fine Photographs’ (the equivalent of ‘Fine Art’). Here is my copy with his contributions. These particular photographs show his celebrity work, especially with US-resident queer artists with whom he was already well acquainted such as W. H. Auden in a strong light, especially their intention to demystify celebrity. Platt Lynes claims the ‘trash can’ had accidentally been newly delivered that day. Auden, it appears felt at ease with the association and irony here. It is very fine portraiture. I want to concentrate though on the Gym Instructor, whom I cannot name, although Ellenzweig might have been able so to do.

The gym instructor though fully clothed is presented in a semi-contrapposto stance with emphasis on the curvatures of his standing body, especially his well-developed torso. The hands are fixed at the hips to emphasise the casual stance but also to emphasise the folds in his clothing and placed to emphasise the arm muscles. The aim is to show power, energy and light – to emphasise the beauty and strength of a man as an attractive image in his own right, in an otherwise totally vacant background. This may or may not have struck viewers as a sexual image – it certainly would strike them as one confident in the appeal of a man as a body first and foremost. All these effects are created by artifice and it is this static artifice which fashion editors increasingly eschewed as Platt Lynes went out of vogue (and Vogue, the magazine, from which he resigned but almost in mutual agreement). Even by 1951 Ellenzweig tells us that the tendency was to collect shots not in studios with an all the artifice of staged attractiveness but ‘out of doors, on locations both mundane and glamorous but, in any case, alive with background incident, caught by hand-held cameras at a fast clip’.[9] That is like neither of the photographs I have just shared, though, in my view, they hold their own modernity unlike some of the ‘Glamour Generation’ such as Cecil Beaton. Tragedy then comes from aging, loss of the looks that characterise youth and to some extent from becoming passé, at least as a commercial artist.

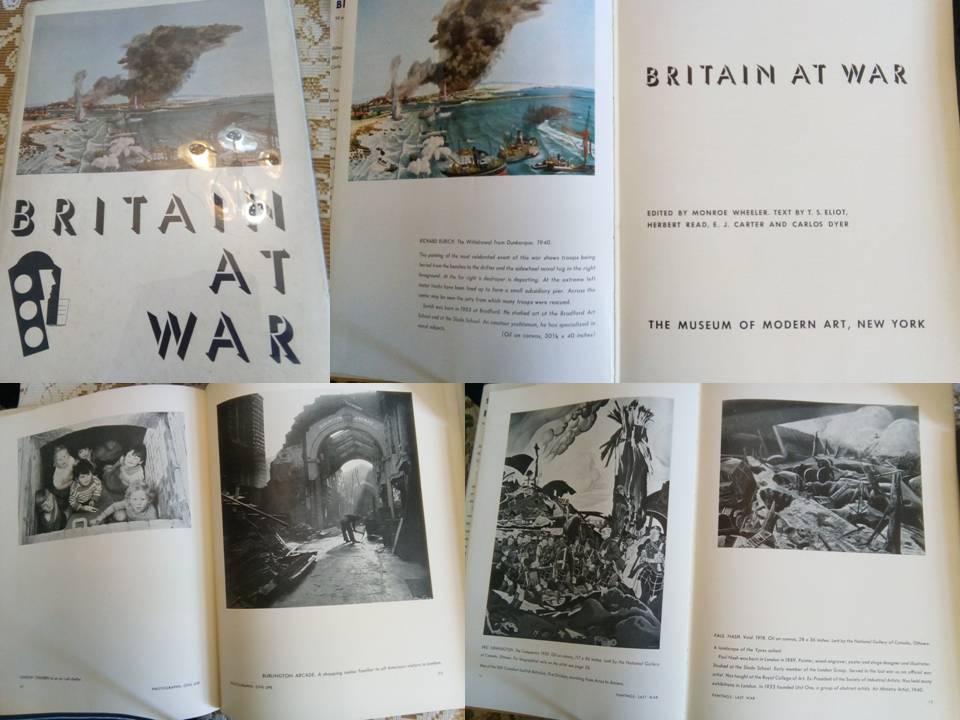

Of course central to George Platt Lynes very being was the idea that he was not merely a commercial artist but an artist per se. This is one of the vast differences between the sexual radicalism of his circle and future queer artists ready to deconstruct what had once been thought of as art and build it anew, such as Robert Rauschenberg. Being part of the company of the three which was Monroe Wheeler, Glenway Westcott and George himself was a commitment to art as strong as that of Cocteau and Gertrude Stein: sometimes with the same self-belief. Platt Lynes wanted to be an artist before he even knew wherein he might have artistic skills. He wasted much time attempting ‘to become a “man of letters”’.[10] Eventually he decided to make fine publications of others’ writing.[11] The publishing profession was, in the end, probably the strength of Monroe Wheeler historically though his amazing literary and visual art compendiums for the Museum of Modern Art are now forgotten, they made selection and anthologising and the use of social influence an art.[12]

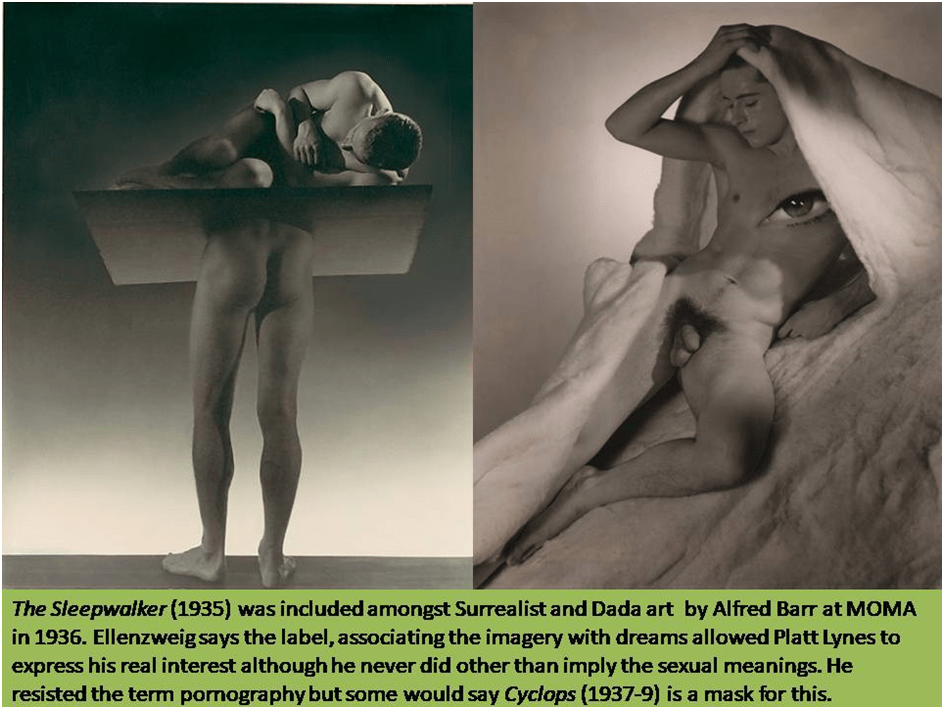

Becoming a photographer meant creating a language for this art and avoiding the categories imposed by others. Ellenzweig suggests that he worked his interests in male sexuality into his work by implication only, notably given that permission by Alfred Barr’s choice of The Sleepwalker (1935) to include amongst the ‘dream’ images labelled those of Surrealist and Dada art in 1936.[13] He may be said to do the same thing with his invention, together with Glenway Westcott, of ‘their series of mythological pictures’.[14] Is the picture of Cyclops (1937-9) though a mask not oinly for the articulation of a new interest in male sexuality or a mask for pornography? It is forgivable to ask this question though Platt Lynes continually denied that these pictures could be described as being pornographic or having that purpose.

He never wanted to commit to label. In terms of Surrealism, Ellenzweig claims he had ‘no interest in the theories and manifestos on which the Surrealists thrived’. [15] Moreover he resisted not only the word ‘pornography’ but even the softer term ‘erotic’ (or even ‘confidential’). He drew the line on Kinsey’s request to show active sex which he did believe would be making pornography.[16] It may be that he continued to believe that the male phallus should be seen as part of a holistic beauty of the body and our negation of that a part of the aggressive sterility of forces that set themselves against the ‘life force’. Cyclops is, after all, a beautiful study of the body seen as a wound and an attempt to escape from that labelling into an openness about the emergent body of modernity.

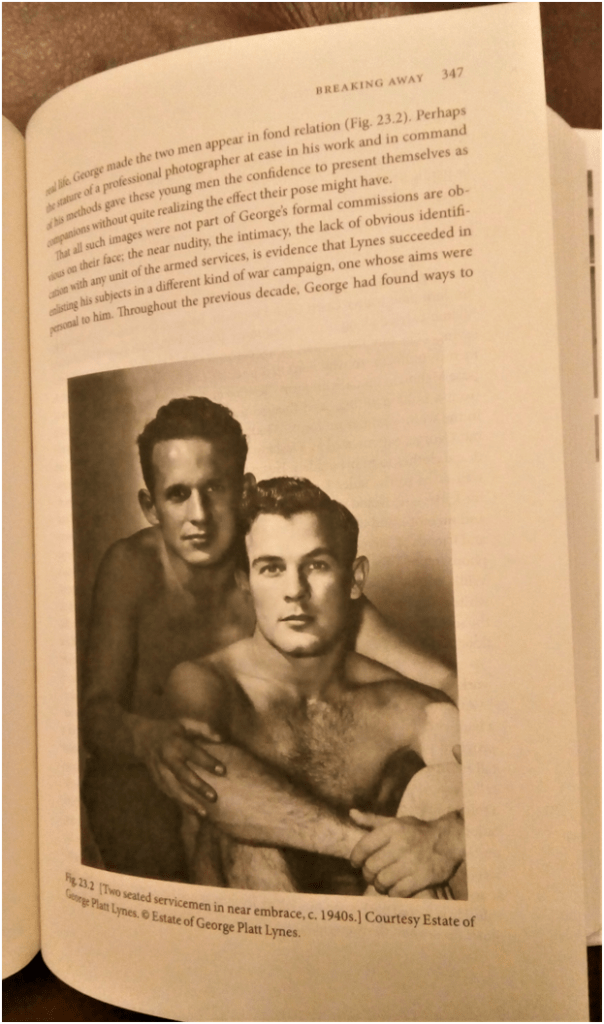

I would I think suggest that we still struggle with these issues. Platt Lynes contrasted the dignity of a great queer artist like André Gide to the ‘charlatan antics of Cocteau’. He admired Gide’s ‘restraint’.[17] Ellenzweig says some of this may be jealousy of Cocteau’s influence but that seems ungenerous. I think Platt Lynes attempted to assert, and seemed to believe with some consistency, that his interest was in the revision of the social image of men from the functionally sexual or socially aggressive to the notion of pulchritude, his favourite term for masculine charisma and the dynamics of the mutually attraction of men to each other. Ellenzweig acts all cynical about this, particularly in perhaps overstressing the amount of which when he made servicemen appear naked with each other and in ‘fond relation’ was entirely a confidence trick played by the suave patrician Platt lynes and understanding the young men’s understanding of the softer meanings implied in their ‘near embrace.’[18]

I think there may sometimes be a tendency to underplay the common awareness of male-to-male tenderness, which may form part of sexual or asexual bonds. Indeed I think the oversimplification of heterosexuality should be no part of the queer paradigm which sometimes reverts to the binary of gay and straight too quickly or without nuance of understanding. Similarly we need nuance when dealing with polyamory, for the ways in which we live and love in groups are so often obfuscated by ignorance, evasions (including flights from ‘temptation’) and sometimes even delusion or lies. Ellenzweig has to read preferences, for instance, in the three way relationship between Westcott, Monroe and Platt Lynes through codes for the frequency of varied sexual encounters within it including those days when they were, as recorded by George: ‘All in bed at 5 together’.[19] Moreover, there is lots of evidence that the failure of their menage á trois left them less cynical about the value of love in all people’s lives than do many broken marriages then and now when they are not only heterosexual marriages.[20]

Another factor that we may have to take into account is that domestic threesomes of men were easier to pass as asexual male buddy groups rather than as domestic couples. One of the saddest aspects of Platt Lynes’ life is that when he moved a new lover, Jonathan Tichenor, into his flat after the failure of the throuple, it was Glenway and Monroe who led the criticism about him becoming, as Bernard Perlin typed their reaction, ‘an open homosexual living with a young man’. One reason for this is this forced Glenway and Monroe to now be a couple living together and that in itself led to ‘malicious gossip’ inside the Museum of Modern Art (MOMA) where Monroe worked that may have lost him his job. [21] We may get all this wrong if we equate the processes of desire with what are mere conventions for its social regulation. That this period was not about political awakening does not mean it was not an attempt to cut through levels of veneer in the way social and sexual models of living and loving don’t always fit those norms.

Read the Platt Lynes biography by Ellenzweig. It is great.

All the best

Steve

[1] Allen Ellenzweig (2021: 214) George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye New York, Oxford University Press

[2] Ibid: 441

[3] Tennessee Williams & Donald Windham (1947: Act II, Sc.II, p.60) You Touched Me!: A Romantic Comedy in Three Acts. New York, Samuel French

[4] Cited Ellenzweig op.cit: 438

[5] Ibid: 439

[6] Ibid: 301ff.

[7] ‘Cut is the branch that might have grown full straight’. Christopher Marlowe’s (1604 text, the final CHORUS) The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus Available: The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, by Christopher Marlowe (gutenberg.org)

[8] Ellenzweig op.cit: 407

[9] Ibid: 435

[10] Ibid: 87

[11] See, for instance, ibid: 55 on negotiations with Gertrude Stein

[12] I have his amazing ‘Britain at War’ catalogue with contributions from himself & T.S. Eliot. In both these cases The aim is to persuade the USA to join the war. Both look to the role of the true artist in war who ‘took up our positions, in obedience to instructions’ (Eliot [piece dated194] page 8) See Monroe Wheeler (1941) (ed.) Britain At War New York, The Museum of Modern Art.

[13] Ellenzweig op.cit: 235f.

[14] Ibid: 277f.

[15] Ibid: 167

[16] Ibid: 427

[17] Ibid: 123f.

[18] Ibid: 347

[19] Ibid: 83

[20] Ibid: 351f.

[21] Ibid: 353-354

8 thoughts on “‘ “… You should be in three places at once, and I loathe having to wait my turn.” …, George expressed in concrete terms the complexities of their multi-level polyamory’. This blog reflects on imaging queer lives and interactions in the light of the concept of polyamory. The blog uses as its case study, Allen Ellenzweig’s (2021) George Platt Lynes: The Daring Eye”