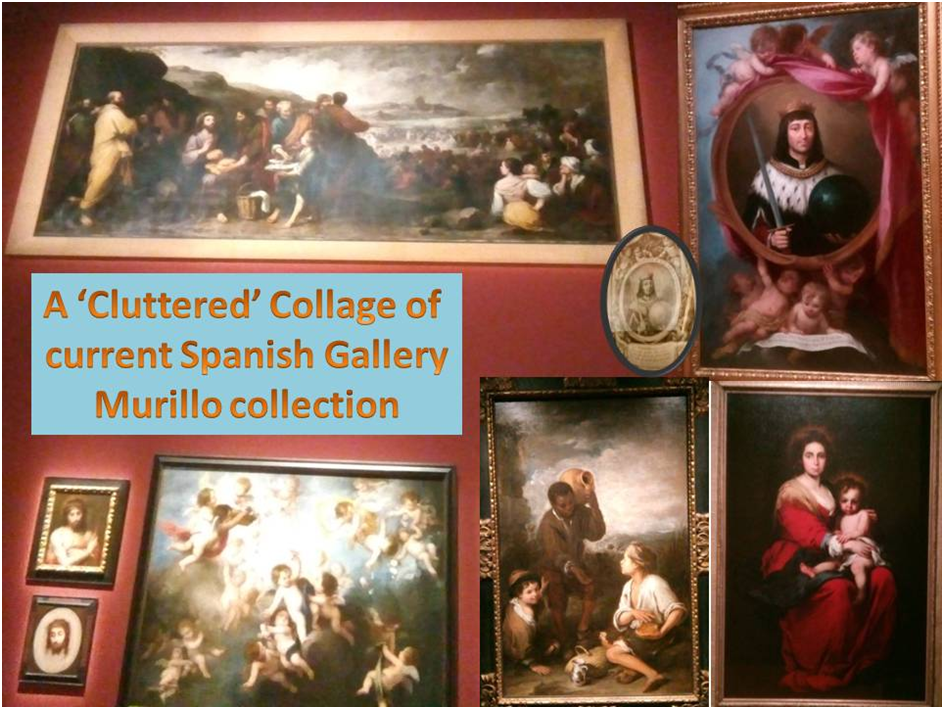

An exploration by an ignoramus of where it might be useful to say that some effects in the art of Murillo tend towards demonstrating that he ‘dissolves the boundaries between art and reality’, and could ‘break down notions of time and space.’[1] : This blog reflects on Works by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617 – 1682) currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland: Reflections and Discussions in my free time on some of the Paintings, as part of a personal learning project related to the Golden Age of Spanish Painting (No.3).

If the holdings of paintings by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617 – 1682) are few in the Spanish Gallery, that is entirely comparative, although Murillo has had a bad press among the established critical authorities in the UK for a long time. His place as the best known Spanish Golden Age Painter in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries has yielded first to Velásquez (and then to El Greco as well).[2] His supposed sentimentality, particularly around the conception of both ‘holy’ and everyday childhood (that of his Sevillian child-models), is often expressed as unlikeable since his images often seem to predict, and certainly pre-date, modern ideas of childhood. These are usually set to commence no earlier than in eighteenth century philosophy and not popularly until the nineteenth. In fact Richard Dorment, reviewing an exhibition in 2001, notes, for instance, that the date at which ‘child play’ became a legitimated concept is usually set after Murillo’s time yet that, nevertheless, in looking at his work he ‘seems to recognise the modern conception of childhood as a separate, enclosed world from which adults are wholly excluded’ that might seem more appropriate in Joshua Reynolds and Thomas Gainsborough.[3] This is often used to explain his popularity amongst Victorians, like Anna Brownell Jameson. This may be because of entrenched sexism because despite the fact that Jameson’s interests are deeply and widely intellectual, she is still often thought to be merely sentimental as the characteristic of a ‘woman’ in serious male eyes of that period and later.

In 2001 Dorment summed up the modern attitude to Murillo’s scenes of childhood as ‘nowadays considered saccharine precisely because the urchins in them are not starving and don’t look particularly miserable’ and as having an ‘acceptance of poverty as a Christian virtue’.[4] The tide in the academic world, at least, may be turning back to seeing the commonalities between Murillo and the other great painters I have already mentioned above as the brilliant work of Victor Stoichita in his 1995 Visionary Experiences in the Golden Age of Spanish Art is better understood and digested. However, in justice to the view in 2001 the reason for the prejudice requires expansion since it is not some stern anti-religious political correctness.

It lies in the fact that poverty in Seville was extremely high (even relative to other Spanish cities like Madrid), as a result of plague in 1649, ‘widespread famine’ in 1651 followed by bread riots in the following year. Plague returned in 1678 accompanied by crop failures and then followed by an economically devastating earthquake in 1680.[5] Now it is clear to any observer that food and its ethical guardianship (in the sense of whether one chooses to share a received charitable benefit in kind or not) is a theme of Murillo’s paintings. None of the people in these sharing dramas in his genre paintings look exactly as if they were ‘anxiously wondering where and how to get a square meal’ in order to survive. It is rather, as Diego Angulo In᷉iguez goes on to say, that the extremely rich Catholic conspicuous consumers of the time were convincing themselves that they (through the Catholic Institutions for the ‘Blessed Poor’) were giving enough to the indigent; it was not just that gifts of food were not being distributed well between the poor.

We will return to this theme when we look at the painting the Spanish Gallery knows as The Three Boys and to the ‘moral’ of The Miracle of The Loaves and The Fishes, of which the Gallery has a brilliantly exact facsimile, although we will find much complexity in attempting to sum up the The Three Boys. But let’s make it suffice here to show the theme in a painting from Dryham Park owned by the National Trust, An Urchin Mocking an Old Woman Eating Migas. There is a special kind of charity that often blames the victim for the fact that the generosity of the ‘haves’ is wasted on the poor morals of the ‘have nots’, who are, as Sancho Panza in Don Quixote says are the two distinct ‘families’ of the world.[6] That concludes the illustration of the 2021 view. It is long-winded but is I think necessary since it remains true that Murillo was the servant, and often without critique as far as I can see, of a very oppressive and deliberately divided and exclusive state of political and religious affairs. It is probably worth remembering the view, however without nuance it appears, that he was an apologist for the religious hypocrisy of the exclusively wealthy, whilst accepting their patronage. For a rich and self-serving aristocratic class like to nevertheless have emphasised to them the genuineness of the charity of Imperial Spain, themselves as its ‘servants’, and its Church without the nuance of critique we find in Velásquez.

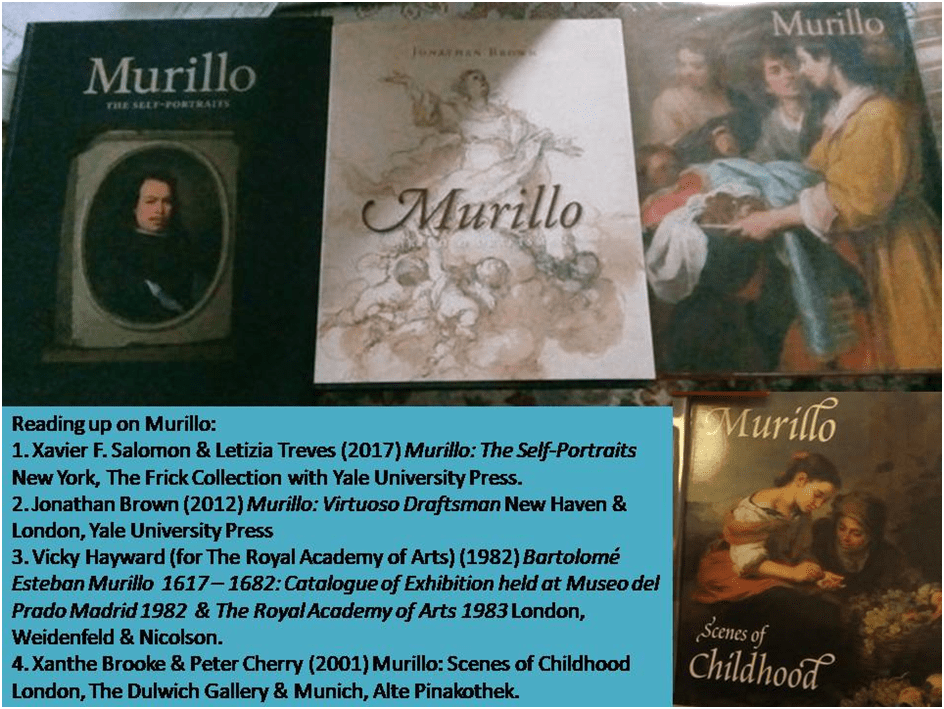

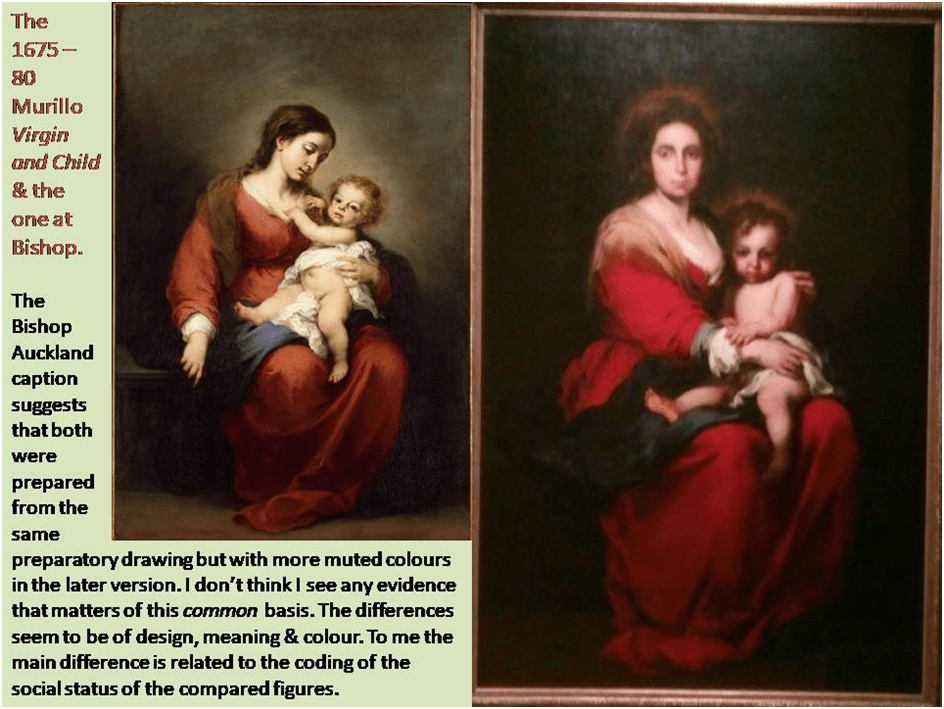

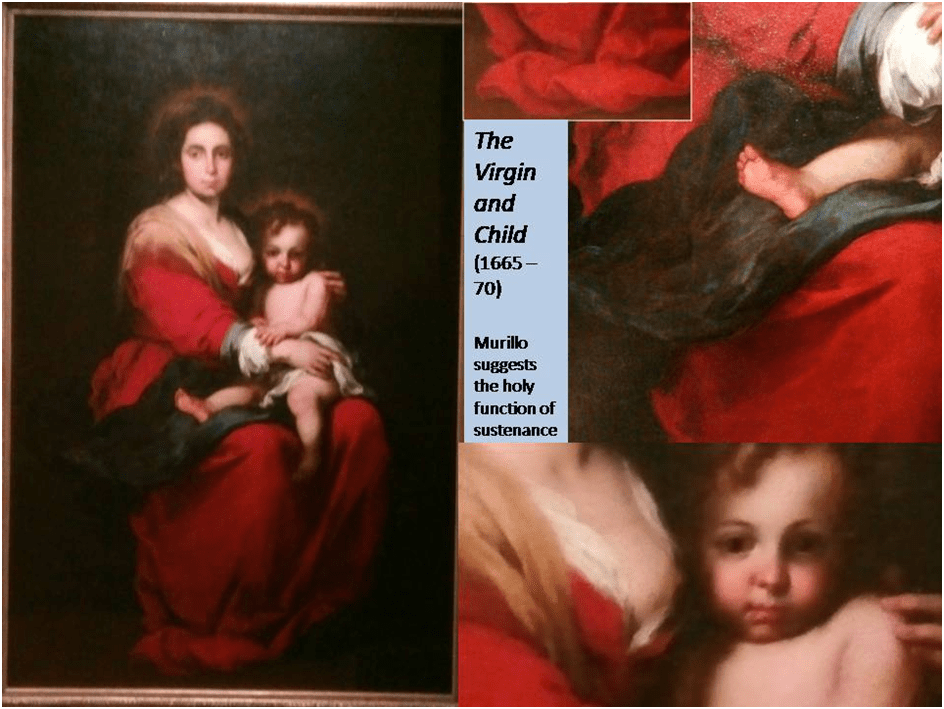

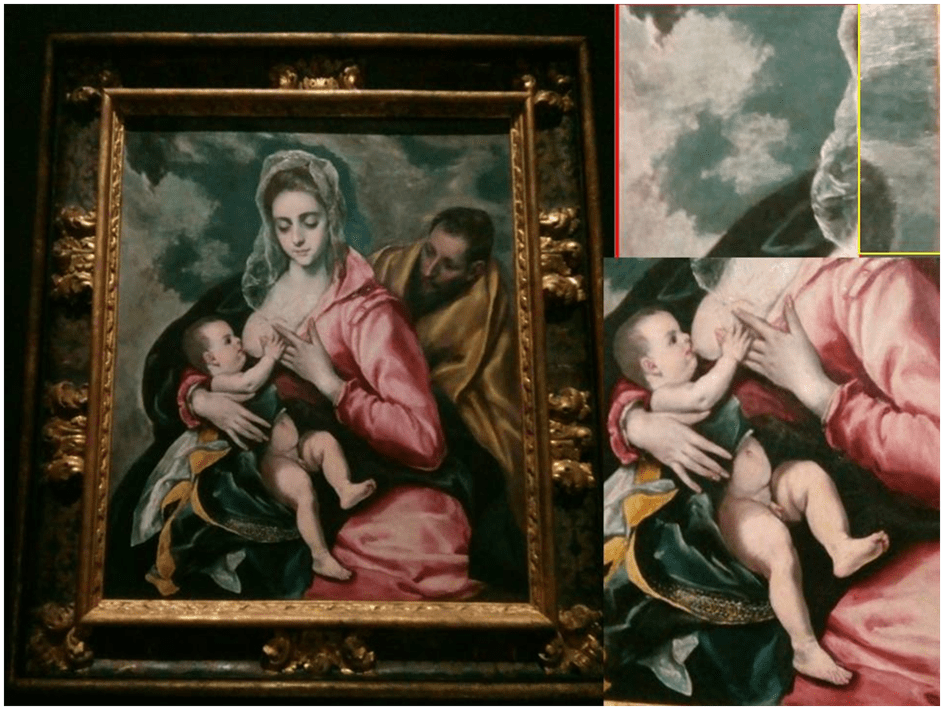

However there is another reason for Murillo’s downfall critically in the twentieth century. That can be summed up as the Baroque excessiveness of Counter-Reformation decorative allegoric morality. We can illustrate this as we proceed. A good place to start with the Murillo paintings held by the Spanish Gallery is their Virgin and Child which is, as the caption to it shows, an early one. It has been neglected or unknown whilst it lay with the family of the Duke of Marlborough until acquired by the Zurbaran Trust. The caption at the Gallery suggests it possibly derives from common preparatory studies to a painting with more muted colouration from about 1675 (about 5 – 10 years later). My search only revealed one that seems to differ in design and meanings too, even those in accidental coding such as dress. However the noted difference in reliance on a greater prettiness (and less realism one might suppose) does seem borne out. One would need to see the preparatory drawings of course but let’s compare them without that.

Where there is commonality between these paintings is in the typical stress on the reproduction of depth illusions in the representation of clothing, especially of the falling folds of female clothing which art historians, have linked – often seeing its genesis in Caravaggio – to other external features of seventeenth-century painting labelled as Baroque: ‘drama, deep colors (sic.), dramatic light, sharp shadows and dark background’. However, historians of both art and the varying cultural display rules of what we call ‘emotion’ (and even philosophers like Deleuze) don’t stop there. The latter, for instance sees the ‘fold’ as deeply characteristic of ways of thinking and feeling that changed historically as things became implicated quite literally with other things. The simplest formulation of this is a continuation of the last quotation from an online art magazine: ‘While Renaissance art aimed to highlight calmness and rationality, Baroque artists emphasized stark contrasts, passion, and tension, …’.[7]

But even if these two paintings have the same interest in the trompe l’oeil effect of ‘folds’, the design of the folds in each is not exactly the same and the orifices and shades of the earlier painting continually implicate the central characters in a marginal darkness and shadowy glory (the latter in the form alone of a vague corona around the holy figures. Christ’s left foot dangles into a lightless chasm In contrast the chiaroscuro, and shadows and shades generally, of the latter painting seems much more rationally explained and his face seeks only those of the viewer to implicate in the prediction of his suffering or invite to vision, not that of his mother. Reminding ourselves of some detail in this painting will help. Christ’s flawless right foot, drafted in total realism is nevertheless set against the dark, indeed black sash draping the Madonna (there are only hints of tonal blue) and a blood red if rich cloth clothing the Madonna. The fate of the black sash is also vague and its extremities hang into and merge with the spectral background in which The Holy Couple sit. Whilst Mary’s clothes are fine and rich, like the lace of her collar, their folds so often creates clefts of darkness and fall at their bases into one such geography od clefted vallies.

Murillo seems to have become, as a friend on Twitter has said, inclined to hide the breast of Mary from vision in the hope of its anticipation being greater than the reality (unlike, say, the very open full-breasted Virgin and Child by El Greco in my last blog (available at this link), who is literally giving satisfactory suck to her Holy Child). In contrast, Murillo aims to draw, it would seem, the viewer’s attention not primarily to the breast but to the expected satisfaction the breast will give the viewer.

His aim is to implicate (or fold into) the story of mother and child the hungry attention of an audience keen too to share satisfaction at the good breast offered. Stoichita has shown that the popularity in Seville of the myth of the Lactation of St. Bernard, where the saint is offered suck of the breast, and indeed in some versions has a fountain of milk shot into his mouth, by the Virgin as she carries the child, who encourages the saint on to fulfilment of eloquence in her favour. Murillo himself did a version of this in about 1660 according to Stoichita but again, as Ian has said, with the breast merely expected, in the process of being squeezed before lactation, rather than given.

Only in Imperial Spain and the Counter-Reformation I think would this play with artfulness and reality bring us back to a metaphor of being fed, so that feeding and poverty are not just real events but also metaphors of being fed from a superior being to whom we are all ‘Poor’. It all depends on the Baroque tendency to conflate all good with what is offered from the superhuman and its avatars, such as the Church and Imperial State. It demands, which is my point, the creation of an apparently solid reality amidst a transcendent visionary space and is one reason that the Baroque erupts from the frameworks it also observes. Stoichita traces some versions of the Lactation myth (especially one earlier than Murillo’s virgin at the Hospital de san Bernado at Seville by Juan de Roelas) to this text from Saint Bernard – pure fare for the Counter-Reformation elevation of Mary;

Mary came to pour salvation’s antidote (…) she bared her breast of mercy to all men so that they might all receive of its abundance, and so that the captive might be granted redemption; the ailing, health; the afflicted, comfort; the sinner, forgiveness. (…) Feed your poor today and give us to drink from your over-abundant pitcher.[8]

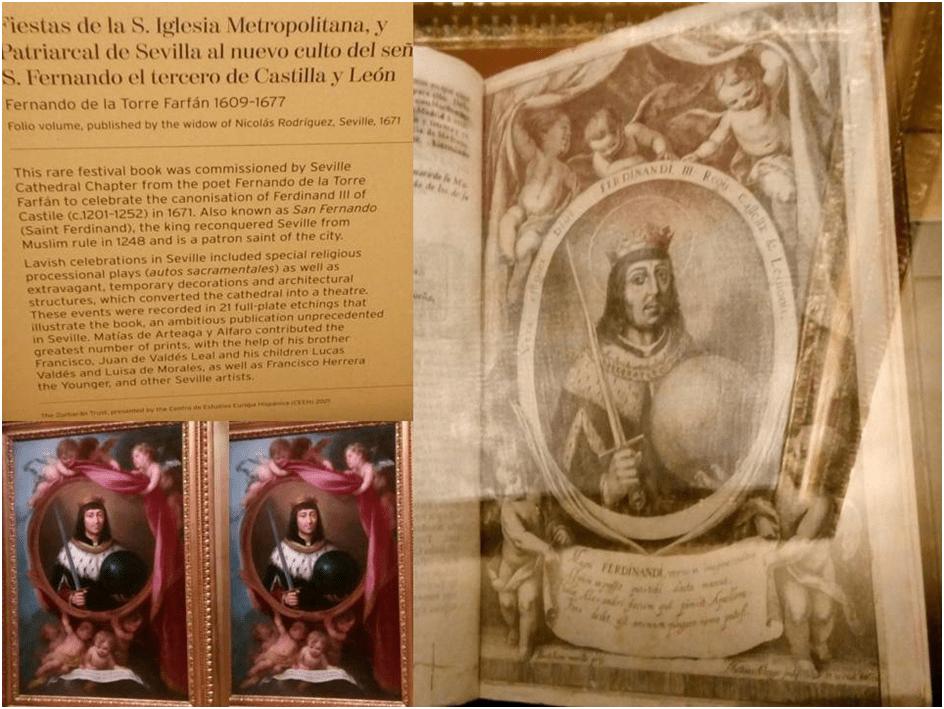

I have tried to show then that in this apparently simple and stock (in some eyes) Virgin and Child of 1650 is the basis of an artist playing with the notion of a timeless and visionary space in which figures taken on a position between art and the invocation of reality, in the hope of manifesting the infinite divine. It is for us to check whether this occurs elsewhere in the Gallery. Hanging adjacent to this picture is yet another ignored painting by Murillo which seems set to be of much importance: his commissioned portrait of St. Ferdinand, the thirteenth-century Castilian King canonised for beginning the ‘clearing’ of Spain of Muslims and starting the union of what was to become the Spanish state by uniting Castile and León.

Art history it seemed once knew the painting as a lost original indicated by an etching of 1671 by Matías Artegas y Alfaro, the year of Ferdinand’s canonisation in the interests of imperial Spain, where it is entitled Ferdinand III of Spain.[9] This same etching however was produced for a book of that year commissioned from Fernando de la Torre Farfán to celebrate the festival commemorating that canonisation. The relevant page of the book is on show facing the original painting, the latter of which is shown for the very first time at the gallery. We can use the etching however to demonstrate how some very small differences made presumably by Artegas y Alfaro, change the relation of picture to viewer in much larger and, for my case, significant ways.

The most obvious difference from the painting is that the etching uses classic Baroque methods to literally stage the elevation of the King’s icon to saintly state. The putti, the humblest and simplest servants of the Deity, stand on a stage set back in illusion from the picture surface level and hold up the icon. Their whole world is a stage with a curtain, enforcing the aura of performance art, festival and the everyday, the divine showed forth to an lower world in the manner of both art and Counter-Reformation ritual. In the original artwork, nearer to its audience, the putti are foreshortened and reclining back into the painting. The painting forgoes the staging of the event and instead the folds of the rich red curtain are in the process of being unwrapped in a revelatory moment by the putti.

I won’t concentrate on the putti here and return to them later with another painting. Instead I want to look at smaller ways in which characteristic depth effects created always in the Baroque very subtly queer the relationship between art and reality, the painted surface image and embodied image. What we see here are some amazingly skilful and under-stated trompe l’oeil effects, an emphasised version of the larger illusion that is illusory depth perspective in painting. Such effects are the rationale of the details in which the Baroque revels: the ubiquity of folded or curved material and objects, the use of edges and ledges with things or flesh leaning thereon, the drama of foreshortening or the layering of objects on apparent planes of increasing depth. Sometimes these effects fail, as I believe them to do in that fantastically disjointed putto at the top of the painting on the viewer’s right, whose fat legs seem to have drifted from the body above to fit them around the inset representation of the oval picture frame.

In the painting it is the inset painted picture frame that serves the function of the stage in the etching, reminding us that this is art, but art of such quality that it seems more like solid flesh and hard material sometimes. Look at the wondrous depth drama of the hands in their plastic solidity. The pudgy one of the putto on the bottom right grasps the frame’s solidity – helping to create the illusion, whilst the hand of Ferdinand above, though framed at a deeper level in terms of a foreshortening perspective appears to project out of its own illusory picture level to that of the actual painting. The painter is glorying here in the mastery of depth and solidifying effects. And, unlike the case in the etching, see how the ruby jewelled hilt of Ferdinand’s sword rests as if on the illusory picture frame which is meant to contain him. Simpler effects such as the superior putto’s hand disappearing behind the curtain thought to be in front of the inner oval frame and of which the rest of his arm forefronts. It is all brilliantly done. And as Xavier F. Salomon says, cited in the passage my title too, of the most obvious trompe l’oeil effect of Murillo’s ‘protruding hand’ from an inset portrait frame containing his 1670 bust portrait (now in the National Gallery in London) such effects had the classical authority of Zeuxis and Parrhasius mentioned in the art theory of Murillo’s own time, what is happening here is to:

- Dissolve ‘the boundary between art and reality’;

- Destabilise ‘notions of time and space’, and;

- Make ‘the apparently distant … closer to the viewer, especially the bust of heroes, saints and artists (including Murillo).[10]

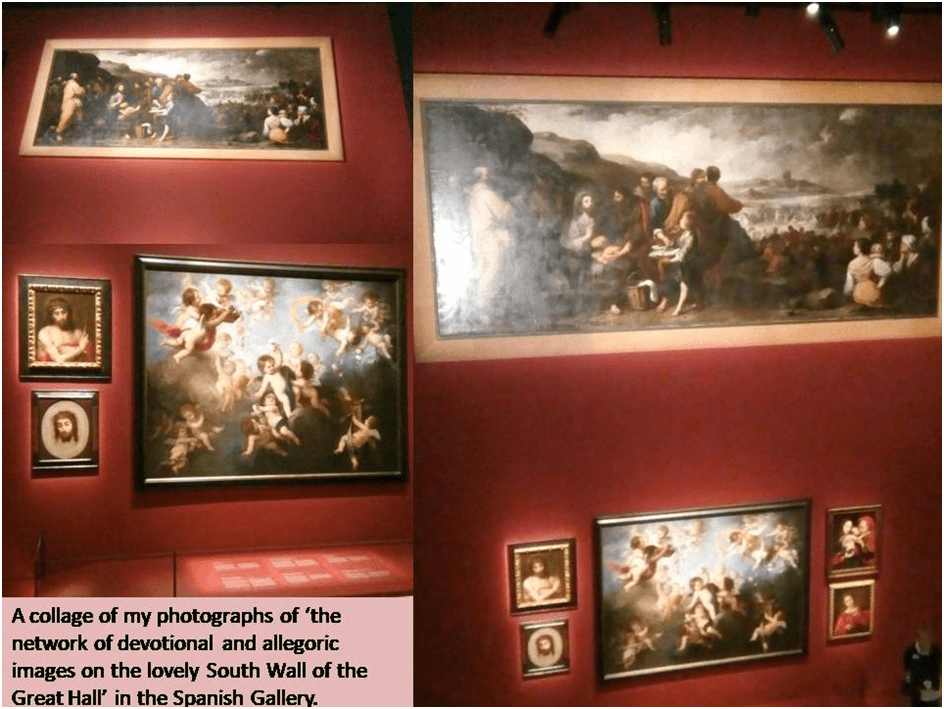

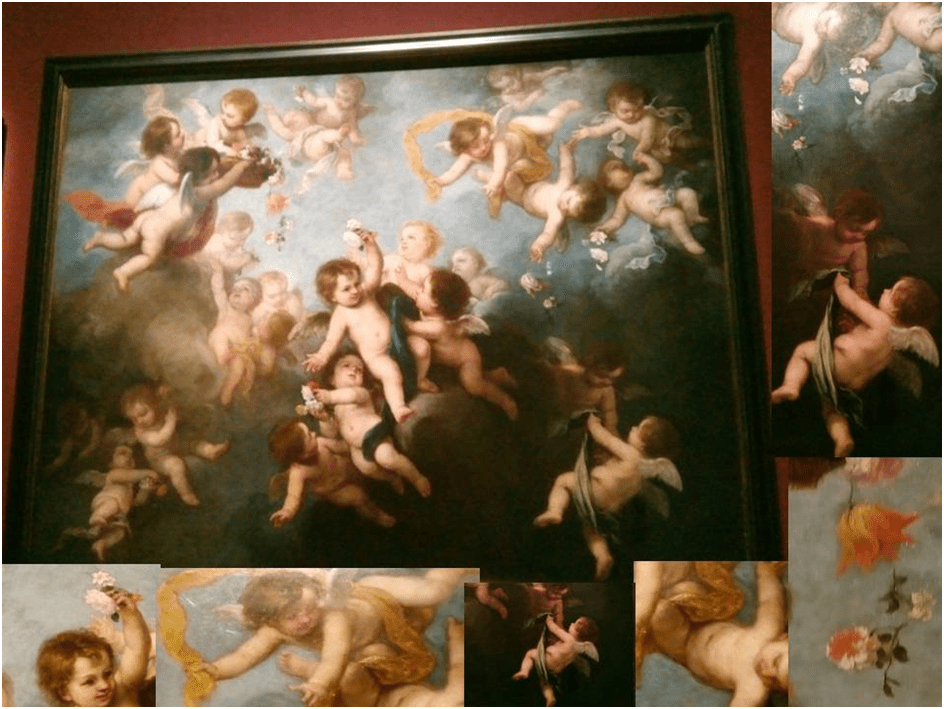

Once you are alive to such effects in Murillo, you begin to revel in them as did he. It is indeed the issues in the process of his artistry which redeems his rather cloyingly intense interests in revelling putti. These I find difficult to take in his spiritual painting, as important as they are to visionary effect according to Stoichita, but in a playful allegory they remind you of the joy that can be found even when in Richard Dorment’s terms ‘painterly values took precedence over content’.[11] And that is precise over the most beautiful Cherubs Scattering Flowers. This painting is under the care of the Gallery entrusted by the Duke of Devonshire during a period of reconstruction at Woburn Abbey. It looks at home here though, even though beautifully built into the network of devotional and allegoric spiritual images of the lovely South Wall of the Spanish Gallery.

It is of course true to say that the joyous putti or cherubs in the painting we are looking at contain all the elements of devotional visionary art outlined by Stoichita, f 21 Theses that conclude his book, although without the ‘uncertainty and vagueness’ that marks the truly devotional but certainly including these stylistics traits (with a more transitionally secular if not pagan reading possible nevertheless):

14. At the time of the Counter-Reformation, the icon/unreal/sacred/transcendence inhabited the top of the painting, forming from that time an upoper level in the representation.

…

16. The cloud is the defining figurative object used to represent the hierophany.

I would suspect that this wonderful painting (it must be seen close to) is as secular a painting as Murillo might paint but its theme is open to spiritual interpretation in that it seems as like a seventeenth century metaphysical poem as anything I have seen. It is a kind of caveat on passing mortal time in its dark worldly sense of loss and a heavenly visionary revelation of eternity.

Indeed the iconography of the cherub is highly confusing in Baroque Spanish art having little in common with the concept of the cherub derived from both Judaism and Islam and still taught in the Church at the time (Milton is nearer the mark though deeply Protestant). The cherubs here are putti which the National Gallery glossary describes thus, giving a clear sense of the confusions that seems to be legitimated by their use from the Renaissance onwards:

Putto (plural, putti) are winged infants who either play the role of angelic spirits in religious works, or act as instruments of profane love. They are often shown as associates of Cupid. They have their origin in Greek and Roman antiquity (the latin word putus means little man).[12]

Somewhere between a ‘cupid’ and an angel, these beings seem at home in themes of temporal as spiritual love, even if the translation of the title as ‘cherub’ is incorrect and based on later assumptions. The notes in Hayward’s Royal Academy exhibition catalogue cite experts who believe it to be a part-piece of a religious painting (with the religious vision above the cherubs but cut off by a Grand Tourist collector of the eighteenth century). Others say it may be the background to an altar sculpture of the Immaculate Conception – one of the glorias of angels for which Murillo’s versions of this icon were especially noted.

Into those speculative areas I do not want to go and talk in the Spanish Gallery currently is that it was commissioned by an ambitious civil servant, Baez Eminente, whose work in customs service reforms lined his own pockets till the inquisition sequestered his assets including this painting. With this I feel more comfortable. These careless babes scatter the fruits of time as if unaware of the mortality of them. The flowers and they convey a youthful freshness and are conveyed in vivid rich colouration and a cornucopia-like abundance of fresh if superficial sheen. Does this painting with its elements that remind us of still-life actually carry a similar meaning – time flies and once scattered will not be regained but in heaven. There is another meaning in which heaven can wait however.

For art is the preserver of trompe l’oeil life. This is for me the meaning here. We know that Murillo possessed and read Carducho’s Diálogos de la Pintura, since we know his copy was purchased in a sale as late as 1709 for a larger than usual sum.[13] And Carducho’s 1634 book including both its images and poems is described by Javier Portús Pérez as having (in a way that has no equivalent in art treatises published until then’) ‘a progressive character’ which progresses precisely to the laudation for the ‘honour and fame reserved for the good painter, who can survive the passage of time and death’ and likens his work to that of God in the Creation.[14] One senses, or at least I do that this is precisely why this painting confiscates the boundary between art and reality and allows a transcendent that is only by extension religiously spiritual.

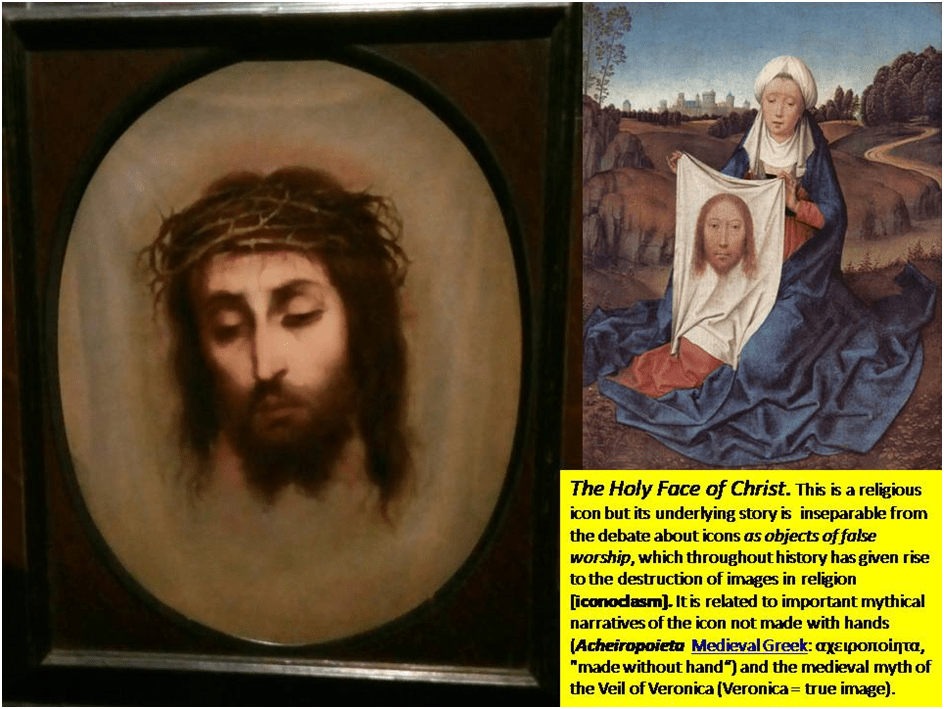

Nothing could be further from that interpretation than The Holy Face of Christ which presents itself as a devotional object in itself, or more strictly in the terms of Council of Trent on the use of religious imagery:

not that any divinity, or virtue, is believed to be in them, on account of which they are to be worshipped; or that anything is to be asked of them; or, that trust is to be reposed in images, …; but because the honour which is shown them is referred to the prototypes which those images represent; in such wise that by the images … we adore Christ; and we venerate the saints, whose similitude they bear:…[15]

This is a religious icon – Tridentine dogma defined the difference between image and prototype thus allowing worship to pass through it if not to it – but the story of this type of icon is inseparable from the debate about icons as objects of false worship (idols), which throughout history has given rise to the destruction of images in religion [iconoclasm]. Those stories are related to important mythical narratives of the icon not made with hands (Acheiropoieta Medieval Greek: αχειροποίητα, “made without hand“) and the medieval myth of the Veil of Veronica (Veronica = true image). Such debates are themselves linked to debates by implication of the role of the artist and often are, despite the Council of Trent, dependent on the qualities of artists to aspire to the God-like role of creation that looked like it was the incarnation of the divine. Other painters admired by Murillo had produced Veronic images with even more emphasis on the folds of the cloth on which Christ’s suffering face had been imprinted by God, such as Francisco de Zurbarán’s 1631 version in Stockholm.[16]

These debates are intensely embedded in theology and ecclesiastical history and I do not intend to rehearse them here but rather just to the point to the relevance to the debate from Carducho we have already rehearsed about the defence of the visual artist. Indeed, according to Stoichita they belong firmly within these arguments since he argues that that the production of ‘Veronicas’ in the period was governed by competition among artists to achieve the most effective trompe-l’oeil effects wherein ‘the appearance of the shroud – its folds and textures – are reproduced with unrivalled skill’.[17] Murillo attempts these, in this version by removing all the usual prompts to reproducing the effect, such as the holding hands which suspend the cloth before us in the Memling example in my collage or the obvious perimeters of the cloth in Zurbarán’s 1631 version. We are still in the realm of art defining its own value here despite the sacred resonances and perhaps deeply reinforced by those.

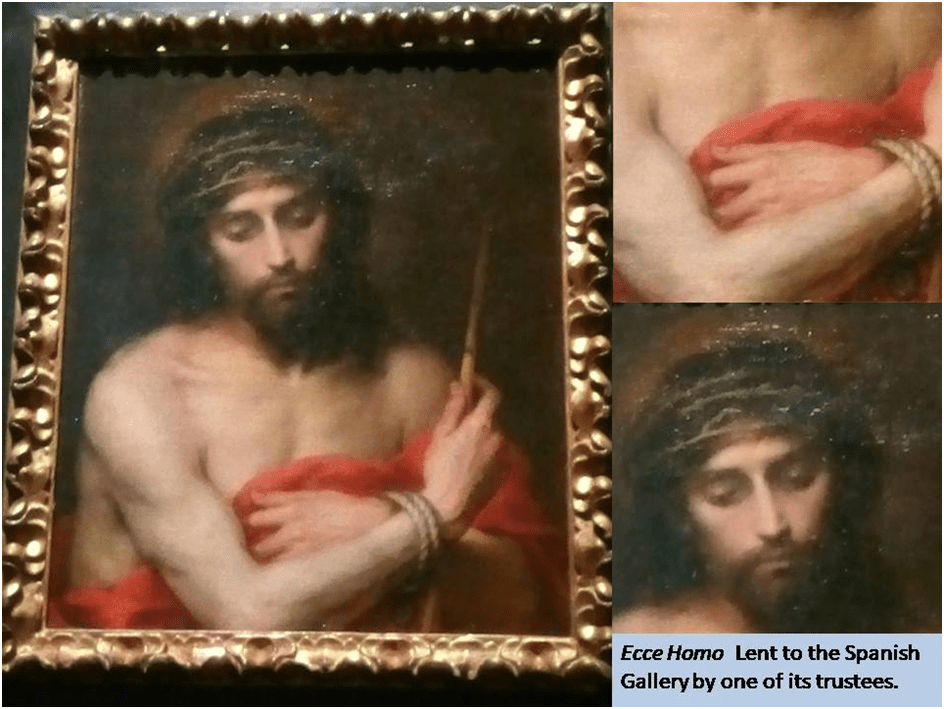

This is even more prominent in that other basic trope of Christian iconography, the Ecce Homo (Behold the Man) image, which uses the words of Pilate presenting Christ before crowds demanding his execution. In the mouth of artists the title becomes a kind of boast of the ability of the artist to rival God in their incarnation of the redemptive virtue of Christ in solid but punctured flesh and muscle, a competition starting perhaps in Caravaggio’s version. Here then is Murillo in a collage I created in order to emphasise the absolute mastery of the trompe-l’oeil recreation of flesh, muscle and even of visible veins and the contours they create in flesh in this version where the pulchritude of naked male flesh is at an absolute premium, whatever the spiritual meaning of the whole. The upper and lower arms of the Christ are placed next to a red folded cloth to compare the classic models of trompe l’oeil. However, it would be difficult to find arms as well sculpted out of soft and plastic flesh than any painter, even from Italian traditions. The realisation of the harder more muscular veined flesh of Christ’s torso and arm contrast with the vaguer (more spiritual in intention perhaps) presentation of the face.

Before moving to the very excellent genre scene by Murillo which is on the first floor of the Gallery, it is worth dwelling for a moment on the digitised reproduction of the narrative of The Miracle of the Loaves and the Fishes which graces the upper part of the South Wall such that it can be seen from many vistas, including a window facing across the Hall but at one floor height in the upper gallery and a specially designed viewing balcony that also has the look of church architecture. I had to reflect here again on The Guardian review of the opening of the Gallery by Jonathan Jones (the link is to my blog on this). Therein Jones sweepingly generalises a condemnation of the Gallery around this painting thus:

There is a truly impressive painting high in the central hall: a huge scene of The Miracle of Loaves and Fishes by Murillo. Its deep shadows and time-deepened hues are so authoritative they dwarf the other art, in quality as well as scale. But oh, wait a moment. This is a fake and openly acknowledged as such. It is a hi-tech facsimile by Adam Lowe and his studio Factum Arte, who mix digital scanning with fine craft skills to uncanny effect.[1]

I hope I have showed already that in considering even other art by Murillo alone, especially original art, this judgement has more to do with the display of metropolitan shallowness than art criticism and helpful evaluation. Moreover, short of visiting the Church of the Hospital de la Caridad in Seville, such facsimiles serve a more than useful service, though the divorce from the idea of religious charity in which the original is embedded perhaps also forces a purely ‘aesthetic’ appreciation such as that of Jones. Diego Angulo In᷉iguez points out that this painting is a companion to an equally large painting in the same original setting for Christian charity Moses Striking the Rock and that together. Moses strikes the rock on God’s instruction; ‘so shalt give the congregation and their beasts drink’.[18] Together with The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes they represent Christian charity in full or as In᷉iguez says: ‘Beneath the cupola’ (of the Church) ‘were placed two enormous paintings representing the giving of drink to the thirsty and food to the hungry’.[19]

It is worth therefore seeing this painting, as we saw the Virgin’s breast earlier and will finally see the Urchins, in terms of the Spanish contemporary concern with food and other physical sustenance, even when it also is allegoric or eloquence, skill or grace as in the case of St. Bernard above. In this light let’s look at my collage:

The clothing of the congregation is that of contemporary everyday Seville, though tidied and cleaned to remove any association with the signs of grinding hopeless poverty such as Murillo would actually see there. The iconography is Counter-Reformation and Franciscan, and like Caravaggio, it concentrates on the naked feet of the main religious figures who are players at the front of the picture frame and at the base of the painting. Strangely enough the poor themselves, such as the urchin at the centre are often shod (rather sumptuously incongruously given the reality outside the Church’s door), to emphasise the currency of need for Catholic charity as a display of humility before even the ‘Poor’, a key idea of St. Francis. The contrasts of dark and light referred to by Jones also make this picture visionary. The feeding congregation at its rear have become bathed in holy light reflecting the supernatural light of the clouds and bathing the distant city (Jerusalem and Seville we take it) as the ‘City of God’ of Augustine. The loaves themselves sit on Christ’s knee and are radiated with his holiness allowing them to take on their symbolic meaning too as the ‘bread of life’. But the symbolic never displaces the physical which is the everyday reminder of its meaning.

I think we probably need to remember this when we turn to the genre paintings including the exceptionally interesting one at the Spanish Gallery, which is on loan from the Dulwich Gallery. What matters in it here is the interaction between poverty and the motivations of humans to obtain, keep and share food resources or otherwise. It is worth visiting the Spanish Gallery soon because I believe this painting is returning to Dulwich in the very near future – perhaps even by the end of March.

Much of the drama in the painting is performed by the hand gestures of the boys, although they remain difficult to interpret as do other features of the painting, including the clear attempt to distinguish the black boy from the white boys by his relatively greater appearance of being comfortably clothed and shod, compare to the dirty naked feet of the boy on the viewer’s left, whose feet project out into the picture frame and are visibly dirty. There is narrative here but our attempts to interpret it are largely second-guessing features. The Dulwich commentary says of the latter:

… his earthenware jug, clothes and shoes clearly indicate he is a servant or errand boy whose position is probably better than that of the white boys, who may have resorted to stealing the pie. The servant boy could even be a portrait of the son of Murillo’s household slave girl, Juana de Santiago, who is thought to have been born in 1658 and whom Murillo freed in 1676.[20]

I have seen no commentary thus far that mentions not only the water-jug borne on the boy’s should and therefore full but the dainty basket on the floor from which I assume contained before empied by the urchins a second jug now stood by it, a rather impressive decorated one possibly of wine or milk, and the pie in the hand of the leftward urchin. If the black boy is a slave/servant of a rich family, the boy’s gesture to the white boy is less likely to be asking for charity but rather the return of bag and contents which have been stolen from him in their transit to his master’s household. This fits some of the coding of the picture better I think and shows that the shopping trip was for a lunch in the richer household. The Dulwich commentary also gives evidence from X-ray that shows that in an earlier version had made the white boys even more vicious in their refusal, a representation he clearly finally rejected in order to soften the consequences of poverty on these poor white boys:

Close examination of x-ray images reveals an earlier composition where Murillo depicted the seated boy with a smirking expression on his face, his teeth bared mockingly. In this version, instead of groping in the standing boy’s pocket, he defiantly pulls the black boy’s hand away from the pie. The subsequent changes to the composition shed light not only on Murillo’s working methods but also on the kind of poverty he wished to portray; he may have found the expression and gesture of the boy too physical and decided to subtly tone down the dynamics of the narrative.

All of this makes me think Murillo was interested in creating a complex picture that backed the ideology of a possibly ‘undeserving poor’, whose vices made them prefer crime to the receipt of charity and who might use any limited power they had to mock those who had the resources they wanted. If so, he relented and, as Dulwich says softens their vices, although the smiling child is clearly (in their reading he is ‘groping in the standing boy’s pocket in the final version’) sharing a joke with the viewer that he can pick this slave’s pocket and abuse him of the fruits of more honest service. I have no great confidence in any singular reading of the drama here myself but I am convinced that his art played two functions: first, to represent the problems involved in the charitable project required of a great Catholic Christian Empire (an Empire emphasised precisely because he chose here to represent a boy whose origin (via his mother as would be the case with Murillo’s slave Juan perhaps) must at some point been human trade in humans. For this trade was a sine qua non of World Empire and in the Spanish version black slaves had, according To J.H. Elliott, a far less empathetic treatment amongst Spanish Christians than Mexican ones. Indeed he shows that in the sixteenth-century, the former paid the price of liberating Mexican slaves who were seen as much more akin to Spaniards than black-skinned races.[21] It is also possible however that the painting is an unexpected articulation for the moral superiority of the black slave. It would be difficult to argue this – as if Spain had its own version of the myth of the ‘noble savage’ well before that emerging in Enlightenment France. Mark Minnes writes of the topic of black slavery in Imperial Spain as an absence in the understanding of the early modern world. It is no wonder then that we may find it difficult to type the allegory, if any, in this picture.

Iberian writers have portrayed Africans in various ways. In exceptional cases, we get to know them as heroes of war, saints, scholars or artists.

More often than not, though, sub-Saharan Africans were farcical and minor characters in popular theater (sic.). They stood out not only because of the color of their skin but also by the way they expressed themselves. In a famous short story published in 1613, for instance, Miguel de Cervantes painted a farcical image of a black slave in Seville. A benevolent character and easily duped, Cervantes’ slave lives in close vicinity to his master’s stables, i.e. the animals.[22]

The catalogue notes in Hayward’s Royal Academy catalogue refer to the painting forming a triangle in which the black boy’s head is the apex, the white boys only its supporting sides.[23] The prominence this structure gives him is not interpreted in these notes but I feel invited to interpret because of the obvious choice Murillo has made to create such a compositional structure. Xanthe Brooke and Peter Cherry in 2001 did think that the painting showed ‘the lack of charity that white society shows to the black population’ and points out that this makes the painting of a pre-nineteenth-century painting ‘even hints at racial friction’.[24]

In the end, hint of this or not, it is difficult to credit the painting with social conscience of any kind, since the drama is reduced to a scene of individuated moral difference, whereas contemporary Seville experienced poverty in the mass ‘when thousands would mill around the Archbishop’s Palace to receive the daily dole of loaves’.[25] In this picture, as in others there is too much provision of food and liquid to take poverty seriously not least in the flesh of the supposed ‘urchins’. Even such moral drama as we see in this painting and other genre scenes are not, says Peter Cherry ‘cast in the in the harsh light’ of the didactic moralism of the contemporary picaresque novels often that are often thought to influence Murillo’s genre painting.[26] If anything the morality is a light reminder that there is no moral haven in the human world.

This could indeed be why the paintings are never recreated as scenes observed in the urban setting where Murillo would have seen starving street urchins. Cherry says they are ‘usually shown outdoors, situated in a no-man’s land appropriate to their marginal social status’.[27] I think this fails to describe the setting we see behind our three boys which is a kind of wilderness but not no-man’s land, whatever that means. Murillo creates a landscape setting full of a vague and numinous natural beauty as we might see in some of the detail I give, particularly of the vague flowers to the left of the head of the boy on the extreme right of the viewer’s gaze. Where all is ‘friendship, eating and play’, or at least potentially so since everyone ultimately smiles the wild landscape cleft on the extreme left of the picture, still vague and numinous but flowered , is a kind of Arcadia. Indeed the soft moral message may be that in all human situations, even in those of children relatively free of adult ‘preoccupations with appearance, status and honour’, we can expect mild instances of sin still to be present: the ‘Et in Arcadia ego’ theme. We might all be reduced to something like the dirt on the feet projected into our vision in this and other paintings. I wonder.

This might be a view supported by Xavier F. Salomon & Letizia Treves’ perception that supposed street urchins ‘are shown in front of rocky structures or ruined buildings … set in the open countryside, with overgrown vestiges of the past behind them’.[28] They say this reflects on the failure of Seville in the seventeenth-century to live up to its role as the true centre of Empire, a ‘New Rome’ as it was once called, as power passed to Madrid and then withdraw further into La Escorial, abandoned by its great people, although Murillo, unlike Velásquez, never followed the court to Madrid. If this is so, and it is a long shot, these paintings may be the mournful remnants of what ought to have the heroic subjects fitted for a great painter modelled after Carducho’s precepts. It remains a puzzle to me.

This is an unsatisfactory place to stop but it does again recognize that the best of artworks in Murillo lived in the cusp between an imagined painterly world and a reality that never quite measured up. However the latter had to be presented as touchable as real things and flesh to reinforce his claims to be a great painter like the heroes of classical lives. My next blog (no. 4 in this series) will be one on of my favourite painters as represented in the Spanish gallery Ribera. Hope I see someone there.

All the best

Steve

[1]Quotations (out of the context in which he more narrowly uses them) by Xavier F. Salomon (2017: 54) ‘Murillo’s Self-Portraits: A Sketch’ in Xavier F. Salomon & Letizia Treves et. al. Murillo: The Self-Portraits New York, The Frick Collection with Yale University Press, 9 – 68. Note that the author applies these terms strictly to the use of trompe l’oeil effects in self-portraiture. I do not know if he believes them to have wider application in the way I use them.

[2] On the shift to Velásquez, exampled in the critical taste of David Wilke, see Brown op.cit: 2

[3] Richard Dorment (2001) ‘Away from the chocolate box’ (review of the Scenes of Childhood exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery) in The Daily Telegraph (Wed. Feb. 21 2001).

[4] Ibid.

[5] Peter Cherry (2001:9) ‘Murillo’s Genre Scenes and their Context’ in Xanthe Brooke & Peter Cherry (ed.) op.cit: 9 – 41.

[6] There are only two families in the world as my grandmother used to say: the haves and the have nots. –– Sancho Panza, Don Quixote de la Mancha, Miguel de Cervantes (as quoted in HumanDevelopment Report, UNDP, 2005) Epigram to essay on globalisation and the role of international monetary organisations available at: (PDF) Globalization and International Institutions: The International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank and the World Trade Organization | Nancy C Alexander – Academia.edu

[7] ‘Art Movement: Baroque – The Style of an Era’ from Artland Available at: https://magazine.artland.com/baroque-art-definition-style/

[8] Cited by Victor I. Stoichita (1995: 144) Visionary Experience in the Golden Age of Spanish Art London, Reaktion Books.

[9] Reproduced in Xavier F. Salomon & Letizia Treves et. al. op.cit: 58

[10] Xavier F. Salomon op.cit: 54

[11] Richard Dorment, op.cit.

[12] Putti | Glossary | National Gallery, London

[13] Marta Cacho Casal (2016: Location 2069) ‘Observations on Readership and circulation’ in Jean Andrews, Jeremy Roe & Oliver Noble Wood (eds.) On Art and Painting: Vincente Carducho and Baroque Spain Cardiff, University of Wales Press (Kindle ed.)

[14] Javier Portús Pérez (2016; Location 16422ff.) ‘Painting and Poetry in Diálogos de la Pintura’ in ibid.

[15] Cited b Terry Prest in https://idlespeculations-terryprest.blogspot.com/2007/03/sacred-images-and-council-of-trent.html

[16] Stoichita op.cit: 50

[17] Ibid: 66

[18] Numbers Chapter 20, v. 8. Available at: https://www.mindprod.com/kjv/Numbers/20.html#:~:text=King%20James%20Bible%20%3A%20Numbers%20%3A%20Chapter%2020,and%20Miriam%20died%20there%2C%20and%20was%20buried%20there.

[19] Diego Angulo In᷉iguez op.cit: 22

[20] Available at: https://www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/explore-the-collection/201-250/three-boys/

[21] J.H. Elliott (2002: 73f.) Imperial Spain 1469 – 1716, London, Penguin

[22] Mark Minnes (2018) ‘Slavery and the Black Presence in Spanish Golden-Age Literature’ A blog by Mark Minnes (30.08.2018) in De Gruyter Conversations Available at: https://blog.degruyter.com/slavery-and-the-black-presence-in-spanish-golden-age-literature/

[23] Hayward op.cit: 191

[24] Xanthe Brooke and Peter Cherry op.cit: 124

[25] Ibid: 124

[26] Peter Cherry op.cit: 30

[27] Ibid: 23

[28] Xavier F. Salomon & Letizia Treves op.cit: 61

6 thoughts on “An exploration of where it might be useful to say that some effects in the art of Murillo tend towards demonstrating that he ‘dissolves the boundaries between art and reality’, and could ‘break down notions of time and space.’ : This blog reflects on Works by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617 – 1682) currently in the Spanish Gallery in Bishop Auckland (No.3).”