‘I say I am a witch, but it is not what I really believe. We are just women with power and skills and an innate knowledge’.[1] This is a blog on critiquing the telling and hearing stories of ‘witchcraft’ in Jenni Fagan’s (2022) Hex Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd.

The cover of my copy of the 2022 first edition as being read yesterday on the train to York

The series of book to which Jenni Fagan is making her contribution with Hex is Polygon’s series Darkland Tales. Alistair Braidwood, for The Skinny, says that this is a series in which a writer takes ‘a dark story from Scotland’s history and reshapes it for a modern readership’.[2] Thus far this is the second of such books, with a third expected in autumn. There is considerable risk involved in the writing of retold history and reviewers can be merciless in their attempts to establish their own authority over such matters. Take Stuart Kelly in The Scotsman; for instance, who often pits his own authority over much better writers:

One thing irked me. When Geillis is in prison, she is visited by a priest. In 1591, it would have been a minister, and I doubt whether holy water or crossing oneself would have been the order of the day. The character seems a cipher for male hierarchy in general. Given that time is somewhat fluid, this may be just a part of the swarm of thoughts, but it jars a little.[3]

What then are the limits allowed to a retelling and what are the consequent detailed research duties laid upon a writer, in such cases? I cannot judge whether Kelly is entitled to be ‘irked’ but his entitlement certainly is flaunted here. The story concerns the genuine historical events around a Tranent maidservant, Geillis Duncan, who was indeed hanged and turned her accusations against her master, David Seaton, at her execution. One source reproduces a woodcut, obviously not contemporary, showing the incident in which she played on a ‘Jew’s Harp’ before James I, whose role in the novel as a representative of male authority is considerable.

In an obvious sense, since Catholic rites were made illegal in the Scottish Reformation, Kelly is probably correct and thus ‘entitled’ to expose something lacking in the writer’s knowledge base. But he does more by, at the same time, making it clear that her error is ideological, in his view, as part of a general attack on the possible representatives of ‘male hierarchy’. Nevertheless, I cannot but smile at the way Kelly uses a more well-schooled (perhaps) knowledge of Scottish history – his specialist subject is the novels of Sir Walter Scott of course, whose freedom with the facts of history is palpable – to put a woman with a fervent belief in a woman’s voice in her place. I say so because David Seaton ( I will use Fagan’s spelling of the name), the deputy bailiff of Tranent who employed Geillis was equally perturbed by Geillis’ knowledge bases, the acquisition of which was inexplicable to him, as the internet History Scotland source says.

Duncan had little in the way of schooling or education, but despite this, Seton (sic.) noted on several occasions she seemed to possess an immense knowledge for healing illness and alleviating pain.[4]

Given that Kelly insists that Fagan makes a solid case for something beyond mere indictment of ‘male hierarchy’ and authority is to his credit. He says pertinently and, I think, truly:

It is glib to think this is #MeToo with ruffs and doublets. The novella insists that what has gone on is still going on, perhaps even more dangerously. … This is similar to the ire that was clear in The Panopticon or Luckenbooth. The problem is systemic, rather than historic. The depictions of the abuse Geillis suffers do not allow the reader to wince. The fact that the behind the misogyny and callously casual sexism is actually a calculated plot involving money, inheritance and power is more chilling. Harm is here a mere means to an end for capital.

But this rather plays down the ways in which male authority (which is never ‘glib’ of course), however structurally systemic in an oppressively structured society, vindicates a greater entitlement to the use of the language and knowledge systems by which it is itself maintained and its maintenance ‘policed’. For it is not only policed by the agents of criminal law but by other institutions – the press, educational practice and literary reviews. And when women show justified ‘ire’ there are still ways that this demonstration of just anger might ‘irk’ a man, or give him the right to name the ‘true’ meaning and target of her anger. Could Fagan come back here to Kelly with a rejoinder that this paragraph of his is yet another demonstration of men controlling women’s stories? She perhaps does not need to, having created from nothing, from the ‘Null’ and ‘Ether her character named Iris. Iris is a woman perhaps from the present time, a witch’s ‘familiar’, and also an imaginary construct – with the wing of a black crow that ‘spans out like an actor’s cloak’ or – a thing made from NOTHING. Is she also an avatar of all women writers? ’After all, Geillis asks Iris: [5]

How come you know so much, Iris?

-Smart women taught me.

-How’d they teach you?

-They wrote stories they were not meant to, were published by others who broke rules to do so, they sang the songs they were not meant to sing, …; they acted in films, on streets, in bars, or i just listened, cleaning loos alongside them, or sat next to a stranger who’d chat away: those are the all women who taught me.[6]

Breaking rules can be a subtle thing. It could lie in using an element in your story that is anachronistic for instance; such as the presence of a priest sprinkling holy water, in an official capacity, in Post-Reformation Scotland. It barely matters indeed whether this rule-breaking with the sequences of time is wilful or accidental. What matters is that it is of consequence that the breaking of the rule is called out, or corrected or interpreted (‘may be just a part of the swarm of thoughts’ says Kelly, kindly (perhaps) of Fagan’s possibly ‘indulgent’ practice) by an authority (a male one of course) other than the mistake-maker. This characterisation may seem unfair to Stuart Kelly but its purpose is to point out the subtlety by which structures of hierarchical authority continue to be reinforced in everyday practices, which, paradoxically, their engineers consider only to part of their situated duty. Iris, thinking about her own time (ours and Fagan’s) says:

… I would like to reassure you that five hundred years from now the fine line of misogyny no lo longer elongates from uncomfortable to fatal, yet I cannot? When you dared to look at those men around you, what did you see? They all thought they were right.

-In everything!

-At all times.

-What woman could question that? A dead one!

-No, Geillis, not even those ones are allowed to be right: not in this life, not in the next. You had as much right as your brother did to hold an opinion. From a child you were raised to hide your hurt lest it offend the boys or men. No matter what they did to bestow it on you, they could never be wrong. If you question your brother, even, who claims to love and respect you, how offended he will be that you think you have the right to do such a thing?> How many times have boys’ eyes (even the nicest ones) looked back at you, knowing with utter certainty that they are right and you are wrong?[7]

Sometimes one wonders how, when their eyes meet such content (rooted firmly in the experienced voice of woman), some men react. Do they ever question their entitlement as a reviewer to be ‘irked’ by a woman making a claim they believe (perhaps correctly), with ‘utter certainty’, to be wrong? A woman must be made to feel, at the very least, ‘uncomfortable’ for such presumption in the attempting to hold the organs that belong more correctly to their brothers, like language and knowledge of history. The point is not about correctness and correction but the utter entitlement with which some groups hold power over others.

And strangely enough the priest in this book, who is at one point too called ‘the minister’, a man who, because of this status, can see the woman behind what everyone else sees as a ‘horse’, only has entitlement over her because he has a penis, and wants that fact to be known. For instance, in telling the story of a witch who collects male penises, he makes it known that even such a wicked man-hating witch warns a man who would choose for himself from the collection the ‘biggest one’ that this penis was, of course, that of a priest. All of this makes of our priest a very self-consciously anachronistic figure (not of ‘male hierarchy’ only) but of secret male fears and vulnerabilities wherein ‘He is lost’: ‘still talking to himself and absorbed in his own journey’.[8] And ‘absorbed in his own journey’ is what male critics too often feel the right to be, never looking once at what a woman’s words truly say.

In the end this novella suggests that the envy of men regarding women may come from the fact that they are created within the body of a woman, and that they fear (or ‘hold a brutal grudge against’) the way in which a creative woman who professes writing might again recreate them in her writing by ‘bringing them out the Null and into this’ by the power of an imagination bold in its own creativity.[9] Hence the reduction of a woman’s night time creative reveries over the beauty of the Bass Rock from the shore of North Berwick can only be imagined by them as a prostitute that demands and steals male potency.[10] That might (helpfully perhaps) be called by a man like Kelly the exercise of ‘magic realism’, but perhaps helpful only because this is a genre already invented by male writers such as Borges and Rushdie.

And should any reader think I am being too hard on Stuart Kelly, I would say: why not! He would never read anything as unprestigious as this blog (read by very few), That imagined reader should try out reading this passage:

Archetypes are always open to re-interpretation. This has very much been the case with the idea of the witch. … The idea of retrospective exculpation is one which I feel certain ambivalence towards: if those women, then why not Margaret Maclauchlan and Margaret Wilson, the Wigtown Martyrs, who were killed under law for their beliefs and without any supernatural suppositions? Why not give an amnesty to every Covenanter, Royalist, Jacobite or, indeed, Thomas Aikenhead, hanged for blasphemy which might well have been some silly undergraduate humour? The past is bloody and it is complex.

You might think there is admiration for a writer managing an archetype with writerly skill but the language here places the critic well above the intellectual level of the writer and exposes her error – that, for instance she over-simplifies history which is ‘bloody and it is complex’. As always in such subtle well-educated discourse, insinuation does more than direct statement in the passage. Insinuation is the privilege of the ironic voice of the critical authority.

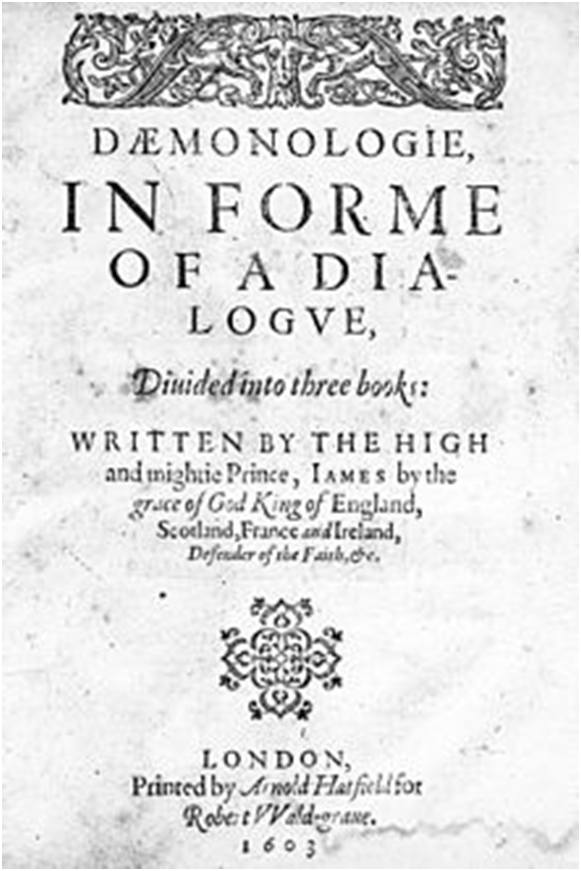

Fortunately, however, ‘Girls learn to shine in secret’.[11] We will learn more about this I am sure in Fagan’s soon to be published memoir, which no doubt a whole army of male reviewers will leap upon to discourse about in the way Jenni Fagan, in their view, could never do as well as them. Lol. There is a hint in this of the role of James VI of Scotland (James I of England) – for secretly queer men are not exempt – since he will, at a date after the events of the novella, write of witches in ways he expected all men and women to believe (and act upon) on his princely authority, in a book. Iris tells Geillis:

They were all things that James VI wrote in his book Daemonologie, the witch-pricker’s bible; he’s just putting down his notes in your time, Geillis, but he’ll publish it before too long. They were crazy things the King wrote.[12]

Crazy men are entitled to write crazy things that justify misogyny. Yet some women writers may never realise, we take it from Kelly’s passage last cited, that history ‘is complex’ in ways feminist readings might say it is not. Of course, again, as Kelly actually says, Fagan attacks capitalist hierarchies too in this novel and in his review that redeems her. But I would say that without the awareness of her queered feminism, we might never grasp how ‘fragile’ a ‘fucking structure’ is the world of male privilege, since it is based solely on projected aggression of a ‘witch-pricker’, indeed a ‘prick’, fearful of losing his ‘cock’ to a witch. In the end Kelly’s last paragraph praises her book as ‘crisp and clear’ and a wanted revision of the kind of Scottish history such as goes on shortbread tins; but is that enough I wonder. For in my view, this book is an indictment of the very structure of male discourse and the means by which it asserts itself whilst appearing to give way to women’s voices.

All the best

Steve

P.S. My other blogs on Fagan’s work are available at the links below:

[1] Jenni Fagan’s (2022: 80) Hex Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd

[2] Alistair Braidwood (2022) Book Review in The Skinny online (28 Feb 2022). Available at: Hex by Jenni Fagan: book review – The Skinny

[3] Stuart Kelly (2022) Book review in The Scotsman online (Thursday, 3rd March 2022, 4:38 pm) Available at: Book review: Hex, by Jenni Fagan | The Scotsman

[4] History Scotland (2021, online) ‘Outlandish fact or Devilish fiction’ (2nd Feb. 2021) Available at: https://www.historyscotland.com/history/outlandish-fact-or-devilish-fiction-the-real-geillis-duncan/

[5] Fagan op.cit: 62

[6] ibid: 38

[7] Ibid: 67f.

[8] Ibid: 81f.

[9] Ibid: 24

[10] Ibid: 54ff.

[11] Ibid: 33

[12] Ibid: 63

9 thoughts on “‘I say I am a witch, but it is not what I really believe. We are just women with power and skills and an innate knowledge’.[1] This is a blog on critiquing the telling and hearing stories of ‘witchcraft’ in Jenni Fagan’s (2022) Hex Edinburgh, Birlinn Ltd. @Jenni_Fagan”