FINAL LONDON ART BLOG (5): ‘If I’m in a positive mood I’m interested in joining. If I’m in a negative mood I will cut things’. ‘… my mother … repaired broken things. I don’t do that. I destroy things. … I must destroy, rebuild, destroy again’. [1] This blog is really a love song to the art of to Bourgeois: The Woven Child London, Hayward Gallery & Berlin, Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH.

Sometimes an exhibition is in perfect harmony with its subject, which in this case is to be big, various and complexly organised enough to accommodate contradictory forms and concepts in one space without damping their effect as single works of art or works in interaction with each other. For Bourgeois herself the problems of space and volume were constitutive of sculptural experience and this may be what she means by saying earlier in her career that she found work with textile antipathetic not only to her art but all art. Lynne Cooke in an essay in the accompanying book to the exhibition cites the artist’s ‘forthright and direct’ opinion: “I have found the medium of weaving incompatible with the art of the sculptor”. Moreover, she further elaborated the cause of that incompatibility to be the absence in woven objects of the ‘”emptiness and the fullness which is essential to the space and volume of sculpture”.[2] I am not pretending however, as more professional and/or academic critics of art often do, that these terms of evaluation are self-explanatory or, strictly speaking, fully explicable except to the sensations they refer to. I understand them in terms of the ways sculptor fills space but only by insisting on a degree of empty space to stand between us and it and perhaps from our penetration of its interiors.

In the best and most appealing, in my opinion, essay in the accompanying book, Julienne Lorz describes the ways in which Bourgeois began to resolve, in her eighties, some of her antipathy to fabric sculpture per se by hybridising it with some of her more monumental icon forms such as the containing frameworks used in her sculptures which she named Cells. These frameworks create interior space and physically distance the viewer simultaneously. Their function was that they allowed her to bring past themes (and forms) together within a hybrid form. Thus:

… various thematic threads, present in previous individual works, are reiterated within a confined space and explored with greater intensity. ‘When I began building the Cells,’ the artist stated, ‘I wanted to create my own architecture, and not depend on the museum space, not to have to adapt my scale to it. I wanted to constitute a real space you could enter and walk around in.’[3]

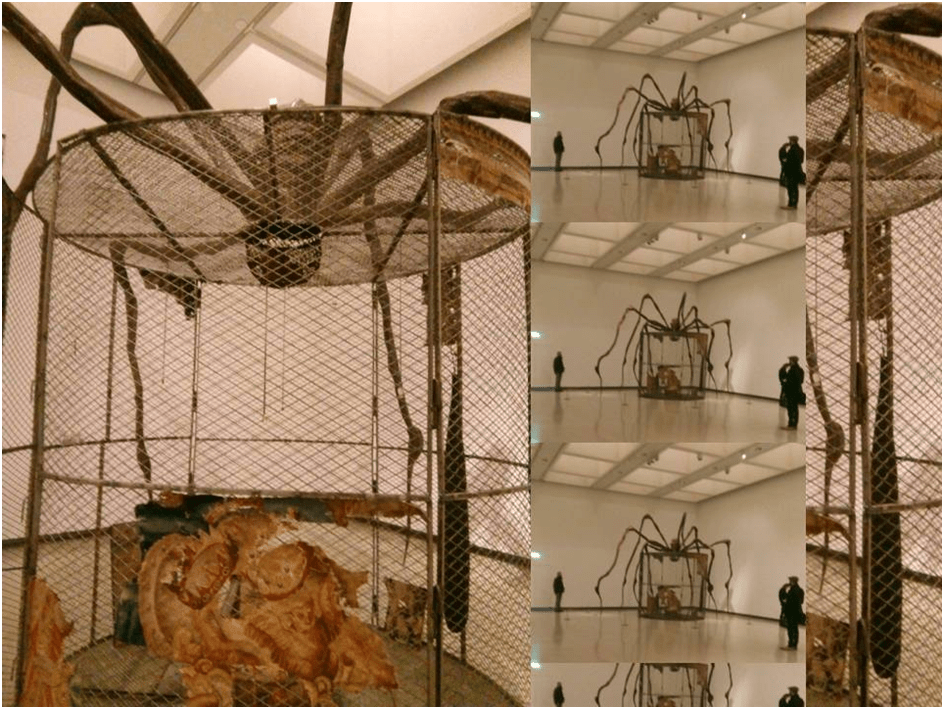

Of course, one cannot in reality walk into the cells. Curators and insurers still insist on distance for security and preservation reasons with even marked distances that indicate the nearest approach you can make to some large sculptures, even the cells. This is true too of touch, which fabric sculpture in particular invites but which museums and their introjected authority in art viewers forbid. Bourgeois clearly knows this, although she encouraged the handling of her sculptures when alive, and is invoking an entry here that is imagined. This is why, as we shall see, her Cells, for whatever reason, have access points. They are doors or windows which are either firmly shut, wide open or slightly ajar (as with the door in the Cell in the large piece known as Spider). Look at these entrances in the collage below for illustration of this point:

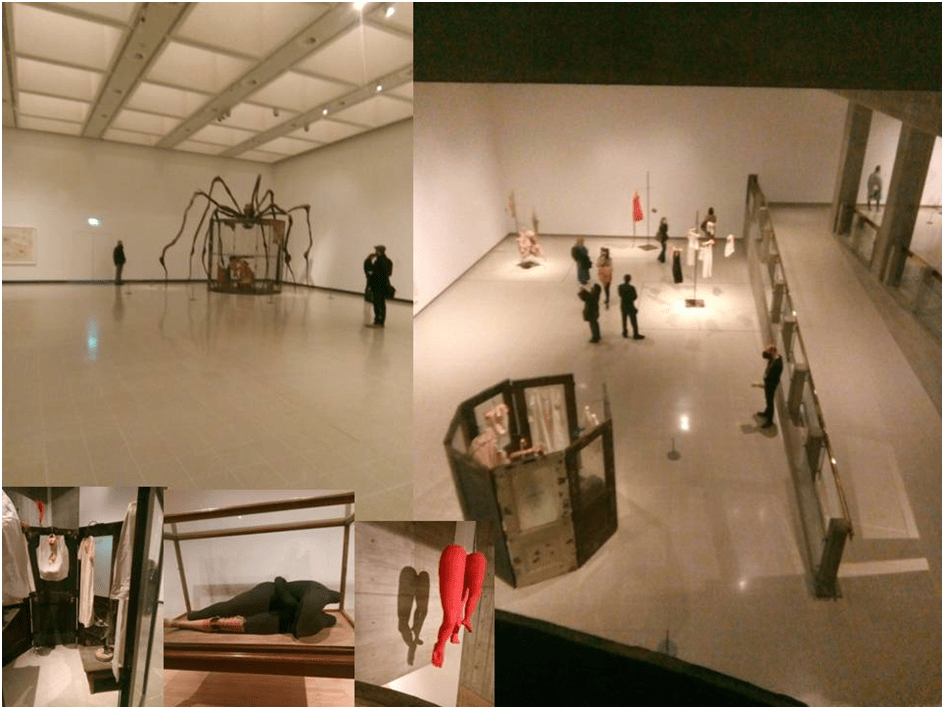

This is not the first Bourgeois exhibition I have seen. Moreover I have seen single works in disparate places but it is the most satisfying, though I clearly enjoyed Tate Liverpool’s more intimate small ‘Artist Rooms’ exhibition earlier this year (see my blog on that exhibition at this link). But in the case of this exhibition the space offered by the interior architecture of the Hayward, with its blind spots and reveals of spaces you have previously trodden, varied levels afforded by a mezzanine between first and second floor and different kinds of experience of ascent and descent, for those who can take the stairways (lifts are available) fit Bourgeois’ complex feel for spatial differentiations in relation to her sculptural work perfectly. You might get some idea of the spatial offerings from the collage of my photographs from the day below.

What I think is worth noticing is how the separate pieces are spaced through otherwise empty space and the variation of viewing points from which the ‘fullness’ and ‘emptiness’ of that space showcases sculptural variation. We see from above on open staircases or from a mezzanine or its ramped approach or stepped egress. Cells are placed in relation to larger architectural spaces and make a point by doing so, especially in approach to larger pieces like Spider.

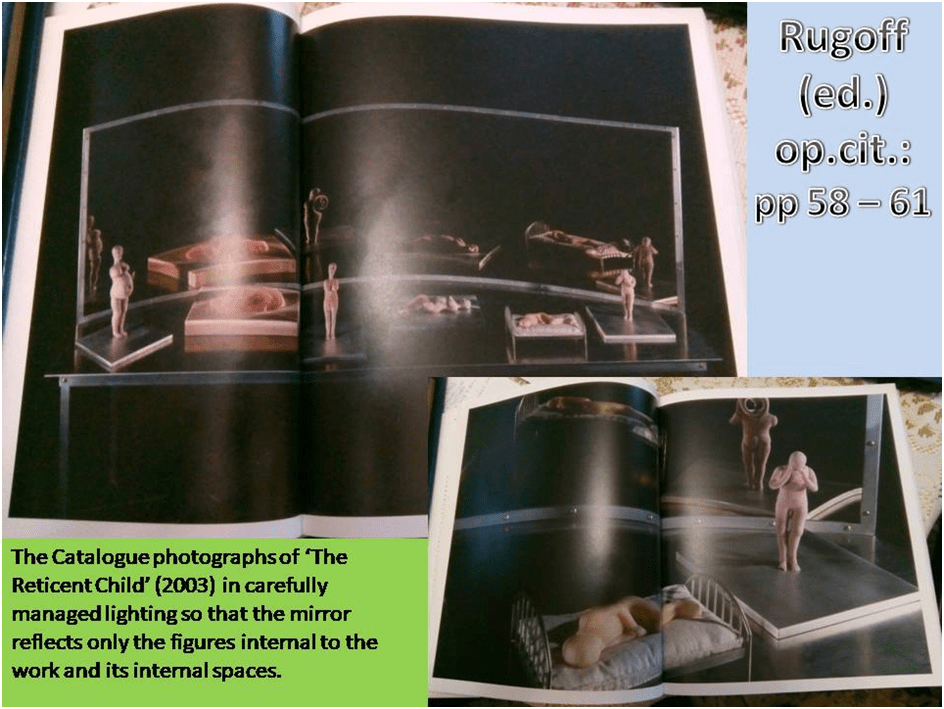

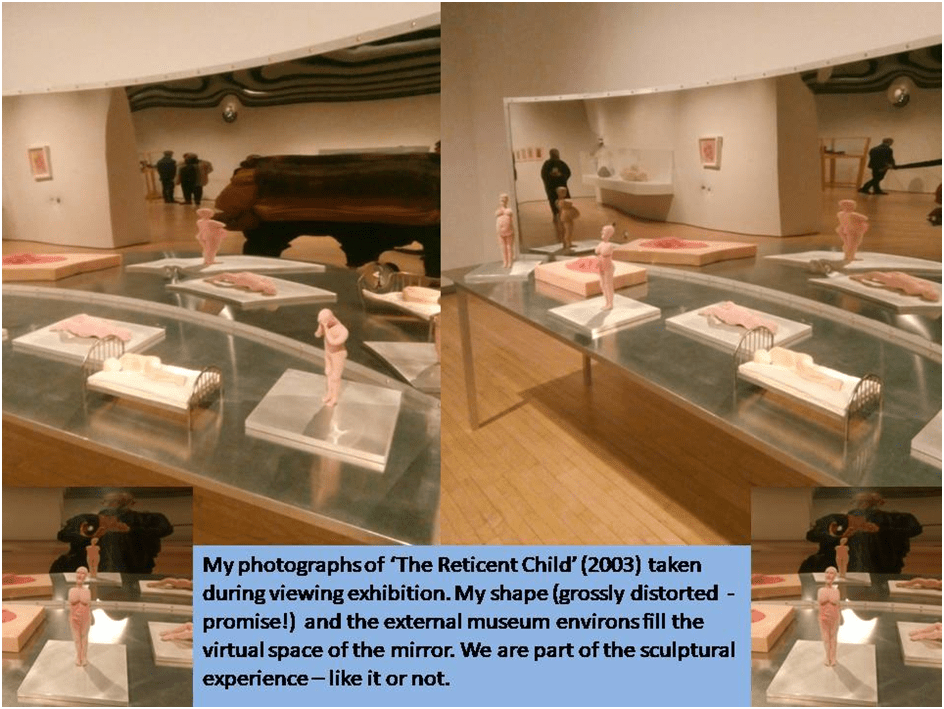

Smaller pieces are likewise placed in environments that emphasise their small size and common vulnerability. This point is emphasised in the piece known as The Reticent Child (2003) which is placed on a steel table backed by a concave mirror. The catalogue photographs it in a complexly lit dark environment so that we see only the reflected (and enlarged) small figures placed as if they are telling us a story (perhaps). In fact the viewer sees themselves – usually their clothed torso in the mirror, uncomfortably enlarged as in a fairground ‘fat mirror’ as you will see in comparing my and the catalogue photography (theirs is better and professional but not therefore nearer to the way we ought to understand Bourgeois’ play with the emptiness and apparent filling of space, that inevitably includes the viewer themselves).

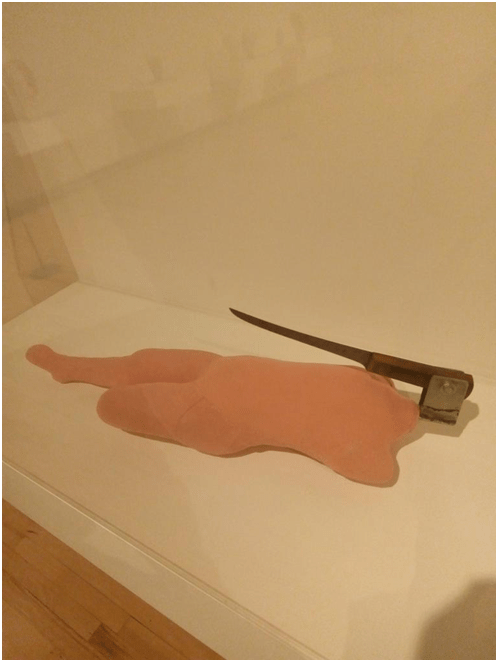

Fabric is a soft material. It yields, even to the eye’s imagination, because it is already filled with substance that repels the viewer or alternatively faces us with the temptation to cut into it. I think ‘The Reticent Child’ plays with ideas of softness and hardness as indicators of emotion and sometimes sex/gender. This is also surely one of the responses we have to the small piece Knife Figure (2002) in which the hard material of a domestic knife is forever suspended above a body of pink flesh-resonant material that it may already have substantially dismembered (of a leg below the knee, arms and head), merely to find its has still no empty middle which the viewer might fill with referential or interpretative meaning. And yet the body looks still like a lump of viscous fluid.[4]

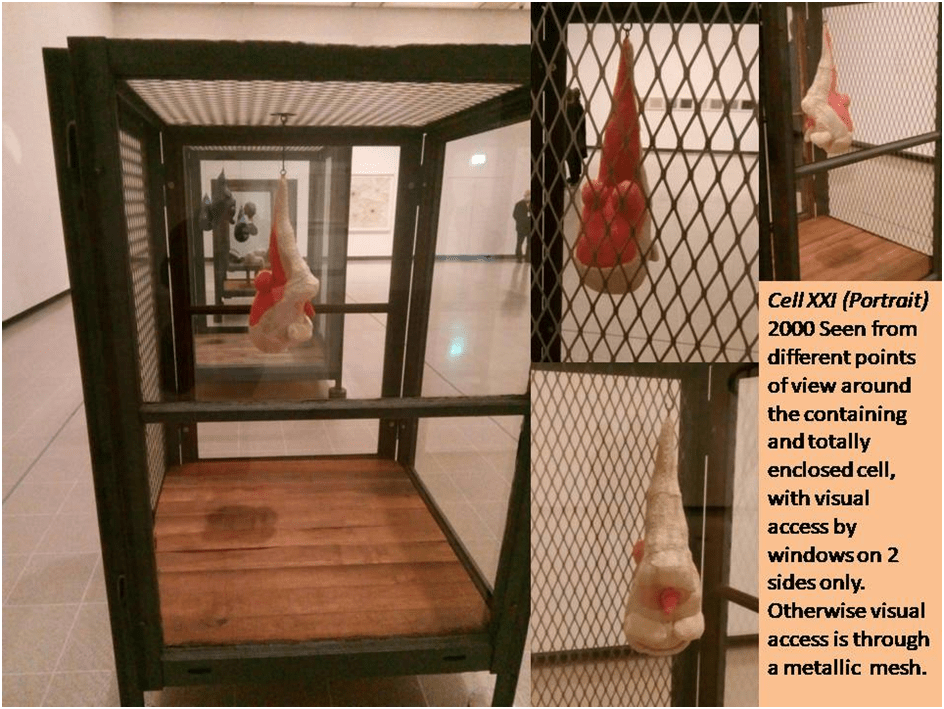

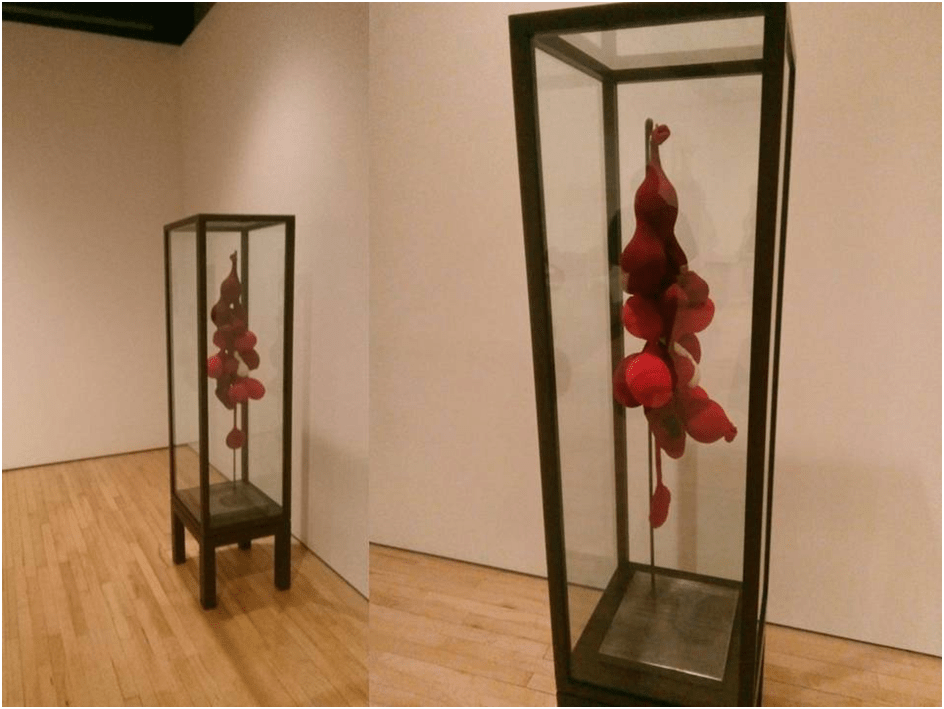

At other times the ‘softness’ of a fabric sculpture is held or contained in the protective shell of an entirely enclosed Cell, which both guards its security and imprisons it. One of the pieces I loved was one such. It is named Cell XXI and is brilliantly described by Rugoff, in a manner that holds me off from attempting another, though it does not discuss the import of the surrounding cell structure, which provides an indubitably hard case to its softer subject, as I hope I show in this collage piece showing different perspectives on the structure from points of view around the cell itself.

Here is Rugoff’s description of the fabric sculpture.

…. a tangled construction of pink and white fabric that can not only be alternately read as referencing bits of male and female genitalia, but that also possibly depicts a pair of breasts as well as upside-down facial features and abstract topographies. The ambiguity in a work such as this goes beyond a simple combining of ‘opposites’ and instead engages the viewer in an experience of slipping from one (often unrelated) association to another in an unresolvable process of interpretation.[5]

That is probably the case though any reader will want to add some dominant associations, such as the memory of meat hung for preparation, the shape and colour of a drop of blood or, on the other side, seminal fluid. But it remains true, as Rugoff concludes, that the ‘categorical fuzziness’ of the concepts evoked is ‘facilitated by’ the fabric construction’s ‘fuzzy surfaces’. Except, and Rugoff does not go here, intervening between viewer and object are different hard surfaces of glass and metallic mesh. These hard distance-creating elements also interact with meaning – for instance the side on which breasts may be indicate is seen through something like a cage’s mesh, whilst the small pink flaccid phallic shape is seen through transparent but still hard and framed glaze. And below the construction is the stain of its shadow on the floor of the cage, which is suspended on feet above the gallery floor but resembles conventional floor-boarding. These points merely amplify Rugoff of course. And supports too his view that Bourgeois late fabric art ‘seems to ask for a distanced gaze, as if we were being summoned to study not a work of art so much as its inner mechanisms’.[6] It rings true too with the way in which the complex coding of the art and the play within it of distance and proximity to our inner lives is, as Cooke says, in contrasting it to woven art preceding Bourgeois’ major intervention, which she saw as ‘delightful’ but as NOT making ‘exigent demands of the viewer as did a work of art’.[7]

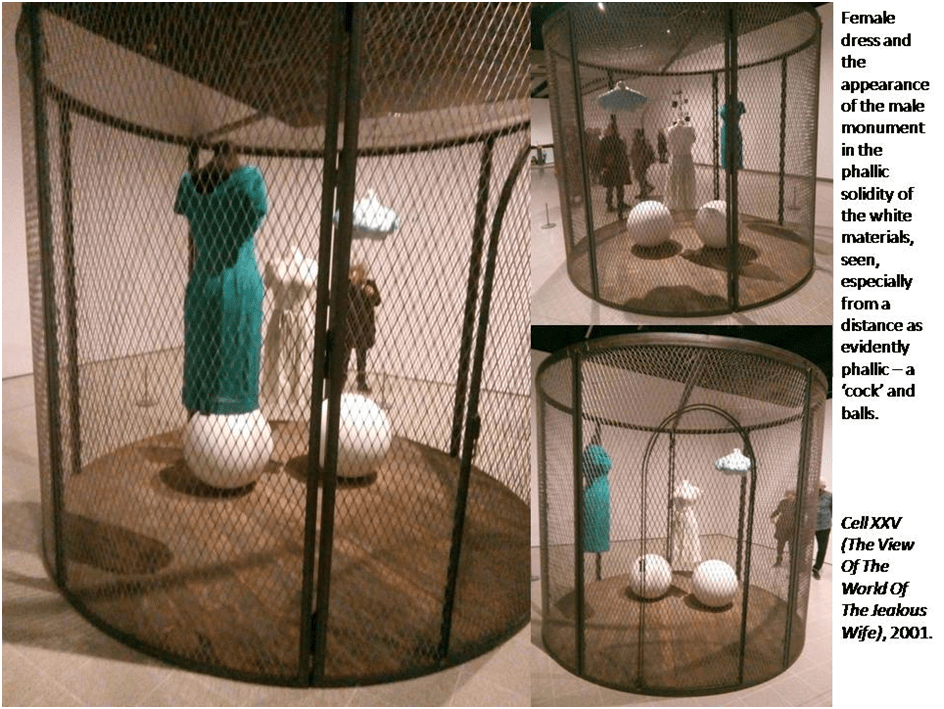

Rachel Cusk in the exhibition book reads this complexity, as I read her at least, in a much more binary way contrasting the pull in Bourgeois between a ‘male’ monumentality in the work to which she aspires, using the ‘solid and permanent materials’ of earlier work and the play with the ‘materials of female disposability’ – clothes and soft materials which are temporary (or ‘futureless’) in their attraction and availability for use – ‘the “flimsy” materials of female monument-making’.[8] Although not discussed by Cusk, I think, Cell XXV (The View Of The World Of The Jealous Wife) uses monumental white to create a faux masculinity, in the form of arrangement of a hanging dress and two large ball shape structures at its base. The arrangement of clothed hanging (wo)manikins within the space appears to show the fragmentation of one woman between several roles and fragments of roles associated with the body or the way in which maleness fragments her attention between self and Other (Woman) with whom she competes and may aspire to be. The Cell itself confirms her entrapment within a realm where power is male or appears to be so. Her only alternative is that she inadequately represents her iconic status and reduces the female to the code given by consumable fabric used for clothing.

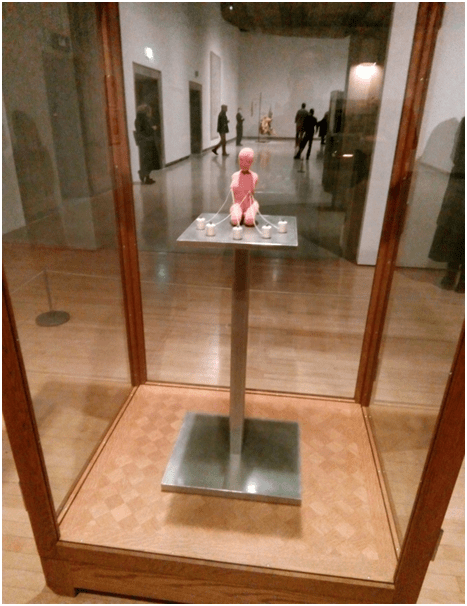

Sometimes women are woven or weaving themselves and others as perishable fabric as in this immaculate small piece. The spools are connected to her nipples and her body is a fragmented construct of flesh coloured cloth with joins at the breast and over her eyes. The potential two-way direction of the thread spools to her breasts suggest that woman make and feed the procreative function, which in turn binds them to motherhood and childlike powerlessness, apparently trapped, contained and belittled) within a biological function that is not valued (if it is patronised by patriarchy) in art or social status.

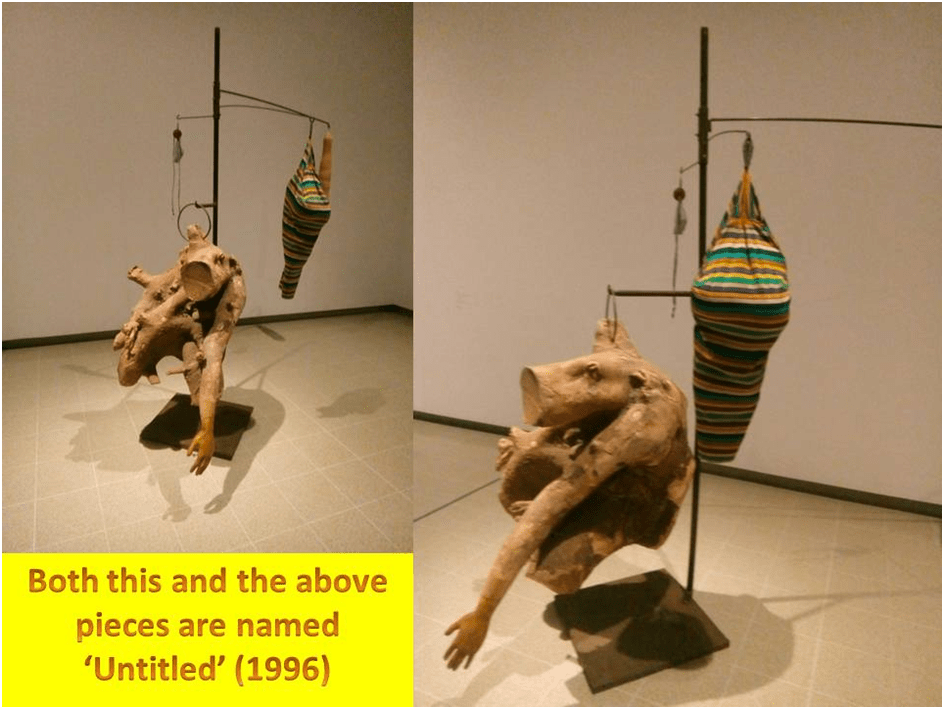

The ‘monuments’ to this are in Bourgeois’ final ‘pole pieces, in which femininity is transformed to sexualised (for the eyes of heterosexual male designers) clothing and hung as a rack for sale and / or display for the purposes of feeding a sexual fetish. That these pole pieces also mask the hanging of meat in a butcher’s shop, where the fragmented body is a woman as animal is conveyed by hanging the clothes on well-cleaned real or fashioned animal bones from different anatomical regions of a large animal but acting as clothes hangers as in the first Untitled (1996) piece below or rendered as mangled and dead body parts or processes meats (hams, sausages and barely recognizable carcases still bearing the likeness of its dead face (a pig here with a woman’s arm and hand suspended as if an udder) in the second piece with same title and date which are the first pieces we see in the exhibition. The point about the second piece however is that the coding of sex/gender is less clear than it is in the first. As Bourgeois’ work advanced I think she veered towards representing the similarity of the softness of inner visceral anatomy of all sex/gender variations rather than surface coding of either body parts or their coded cultural dressing.

In Untitled (1998), contained in a vitrine (as if a valued piece perhaps ironically, the viscera are rounded, appearing as breasts or perhaps gonads or as functionally non-sexual inner parts. The white piece recalls, being pendulous, a penis (or a clitoris perhaps). Here ironic valuation of the soft viscera is, I think, deliberately coded confusingly such that binary divisions of male and female are not so easily interpreted from them.

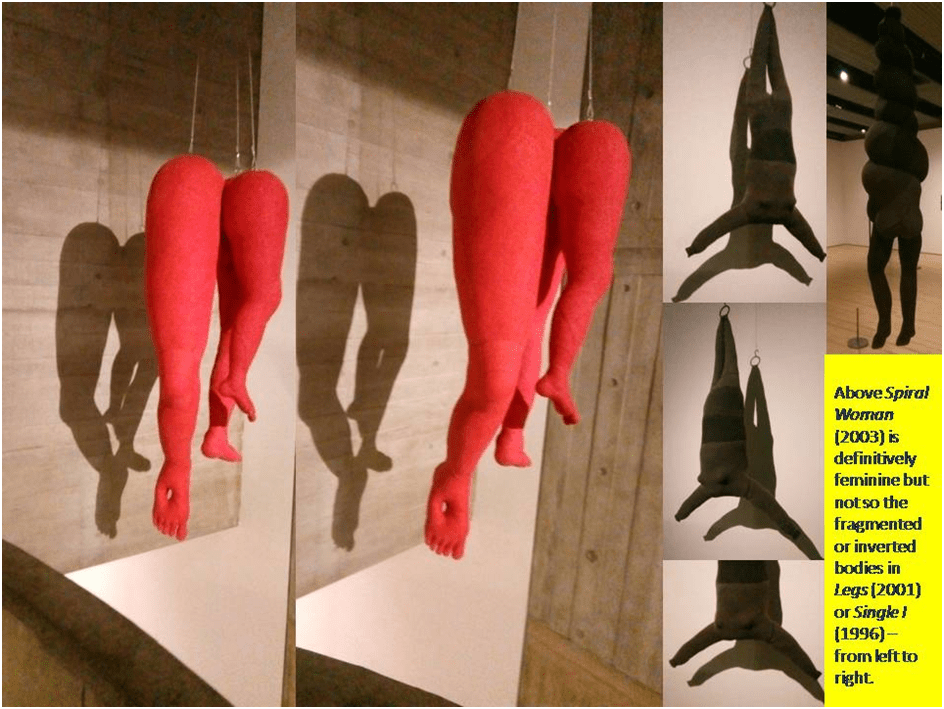

Sometimes the representations of the body are suspended from a hook in this show as parts or wholes. Sometimes their meaning seems simpler as in Spiral Woman (2003), which is definitively female in its coding as well as title, although mainly associatively, through curvaceous soft structure and body attitude (none of which are biologically determined entirely). However the suspended work Legs utilises its ‘third middle leg’ as a phallic substitute in part (remember that slightly distasteful Jake The Peg song by Rolf Harris) and one foot bears a stigmatum of a pierced foot. Both pieces facilitate use sculpting of their shadows in light to complicate their categorical identity (we see hearts, anuses and non-binary leg interweaving in Legs and can see Single I as a phallic symbol with the ‘breasts’ as gonads, especially given the child-like leg appearance of the ‘arms’ of the piece in shadow.

Those works stun in part because of the quality of the curation, including the planning of the discovery of the works. Single I appears on an intermezzine landing as one climbs to the first floor, Legs at a parallel landing on descent, where one also views our entry, as in the photograph opening this piece. It is not only skilful. It is truly co-operative artistry with the dead artist, communing with her through her work and writings.

However if we return to individual works, we ought to notice that even when phallic reference is intended as an immediate marker of the masculine, my feeling is that it recreated such that sex/gender coding is complicated by the materials, their colouring or gestural presentation. For instance a small male figure with a semi-erect phallus is suspended as the form she calls an Arch of Hysteria (2004 – the motif is discussed in my last Bourgeois blog) as in the Harlequin figure below, or the cushioning effect of the manufacture of the symbolic phallic erection (again below – Untitled 2002). Bourgeois’ creative process of destruction and rebuilding, even of the codes by which we live, allows her to rebuild not only to celebrate what was once a symbol of naked power (like the phallus) but to repair in ways by which life is degraded.

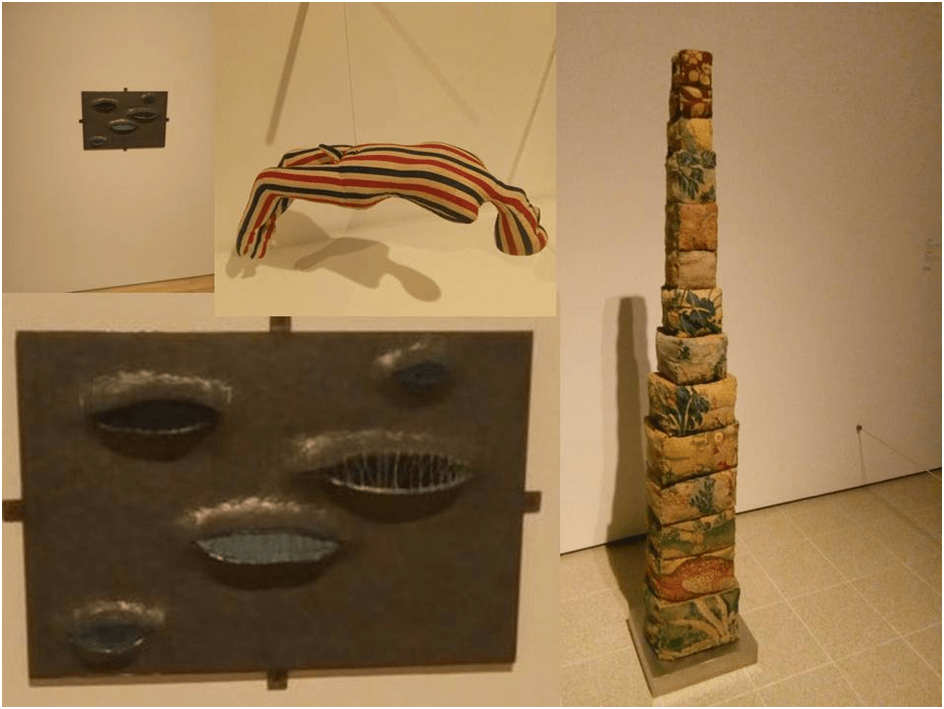

Lorz cites her 1989 statement that: “Sewing implies repairing. There is a hole … you have to hide the damage … you have to hide the urge to do damage”. And you end up by causing greater damage by the act of repression. Our ability to speak the queer for instance is silenced by suturing of mouths. This is the painful message for me in the work below named Repairs In The Sky (1999). It is a hard metal plaque (lead and steel) containing orifices which have been roughly ‘sewn’ together (in appearance) half-closed and which recall simultaneously the vagina, mouth or eyelids – points of access to the body or ways of communicating its truth – now rudely shut by their apparent ‘repair’ to a recipe not conducive to their most appropriate function.[9]

Some critics have pointed out that Bourgeois has used disability caused by the loss of limbs as an emblem of sexuality under conditions of difference, in ways I personally never feel comfortable with. Thus I do not feel I can respond well to the use of disability as a motif in a work such as Couple IV (1997), if that indeed is the case. I have never seen the need to make disability by limb loss or dysfunction as symbolic of the dysfunction, fragmentation or queering of sexual coupling, where that does not reference disabled people’s own experience, as referred to by Cusk who says that ‘the woman retains a vestigial artificiality by which she can be identified’.[10] Instead the small work Couple (2001) minimises sexual difference and uses sewing together of bodies as a means of the attainment of some similitude of pleasure and emotional satisfaction, but I will leave a comparison of the two to anyone reading this – if anyone.

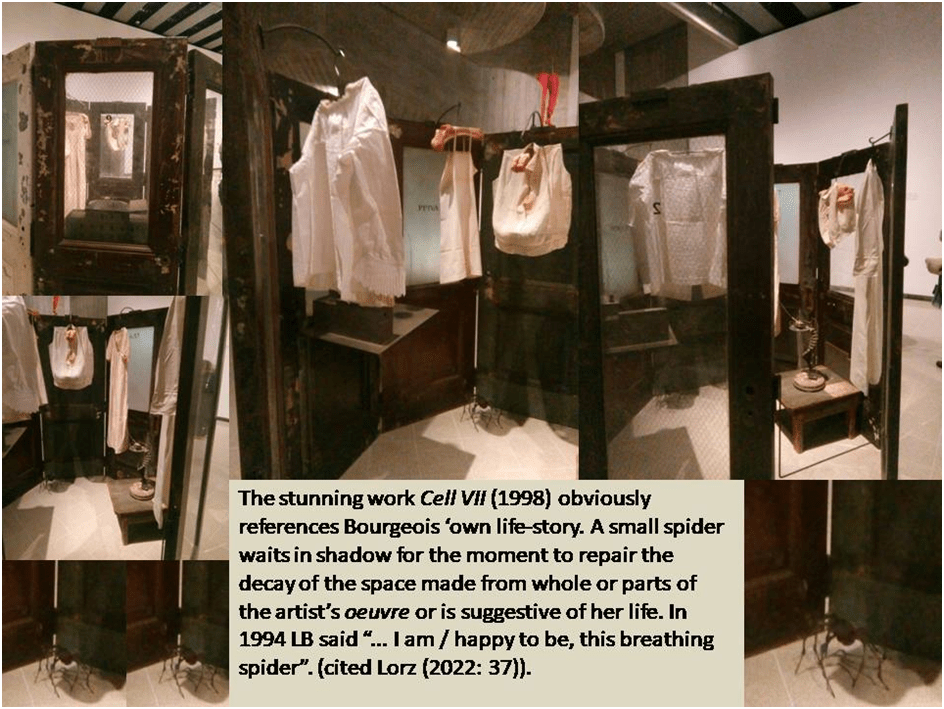

I have already referred to the excellence of the essay in the exhibition book by Lorz, and i think this is so not only because she opens up the theme by which the couple can be re-examined, which is the analysis of her work using psychoanalytic understandings of reparation in Bourgeois. The stunning work Cell VII (1998) obviously references Bourgeois ‘own life-story and is an attempt to re-integrate its parts. A small spider waits in shadow for the moment to repair the decay of the space of which the clutter of furniture is made from whole or parts of the artist’s oeuvre or is suggestive of her life or work (as a child in her father’s tapestry repair firm and later as a recall of the same in part as an artist). In 1994 LB said “… I am / happy to be, this breathing spider”.[11] For both needles and spiders are icons in her work of repair that might destroy in some cases (a spider weaves to kill its prey and survive upon it) whilst needles repair but also puncture and wound. At other times she uses the French term for spider (l’araignée) for her mother but as an ideal. Lorz cites this bi-lingual piece from Ode à Ma Mère (1995).

The friend (l’araignée – pourquoi l’araignée) parce que my best friend was my mother and she was deliberate, clever, patient, soothing, reasonable, dainty, subtle, indispensable, neat and useful as an araignée. (My italicisation)[12]

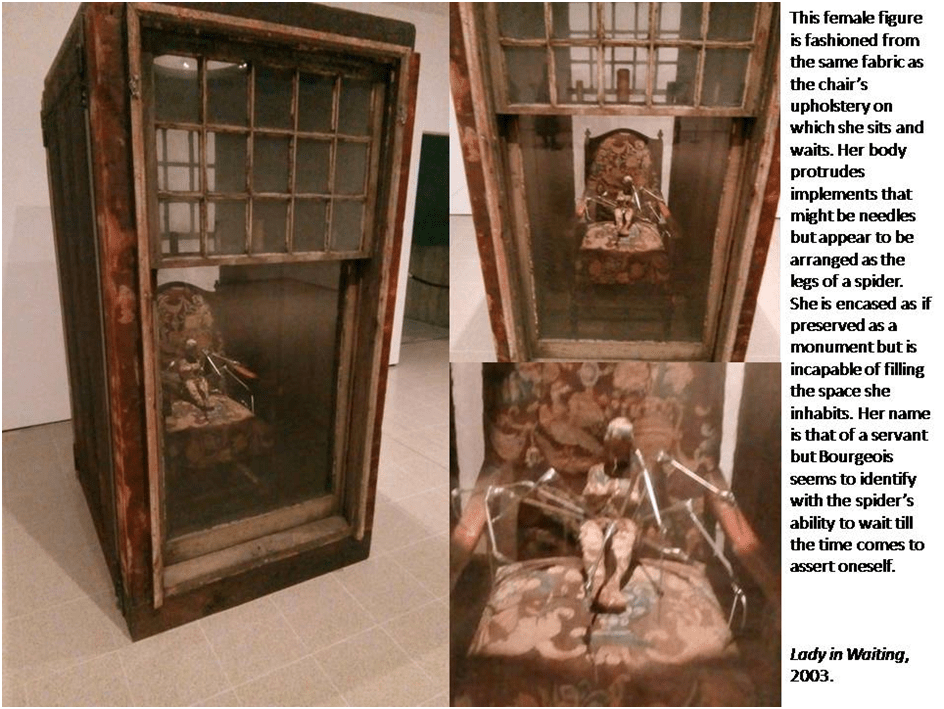

In a more contemporary work Lady In Waiting (2003). My reading below owes almost everything to Lorz. The Lady in the work is a type of Arachne from classical culture, long celebrated as a type of the human artist’s aspiration to the divine as by Velasquez. In Bourgeois waiting is a kind of ‘patience’ (imbued with divine value) but also the sign of female servitude. As the central female figure in the work, the Lady is fashioned from the same fabric as the chair’s upholstery on which she sits and waits. Her body pushes out implements that might be needles but appear to be arranged as the legs of a spider. She is encased as if preserved as a monument but is incapable of filling the space she inhabits. Her name is that of a servant, as already pointed out, but Bourgeois seems to identify with the spider’s ability to wait till the time comes to assert oneself. Lorz reads this waiting negatively as ‘anticipating an event that will never happen’ but that alone I find an over-reading since Bourgeois still awaits after death and in some way has triumphed over the conventional and classical gods of monumental male art.[13]

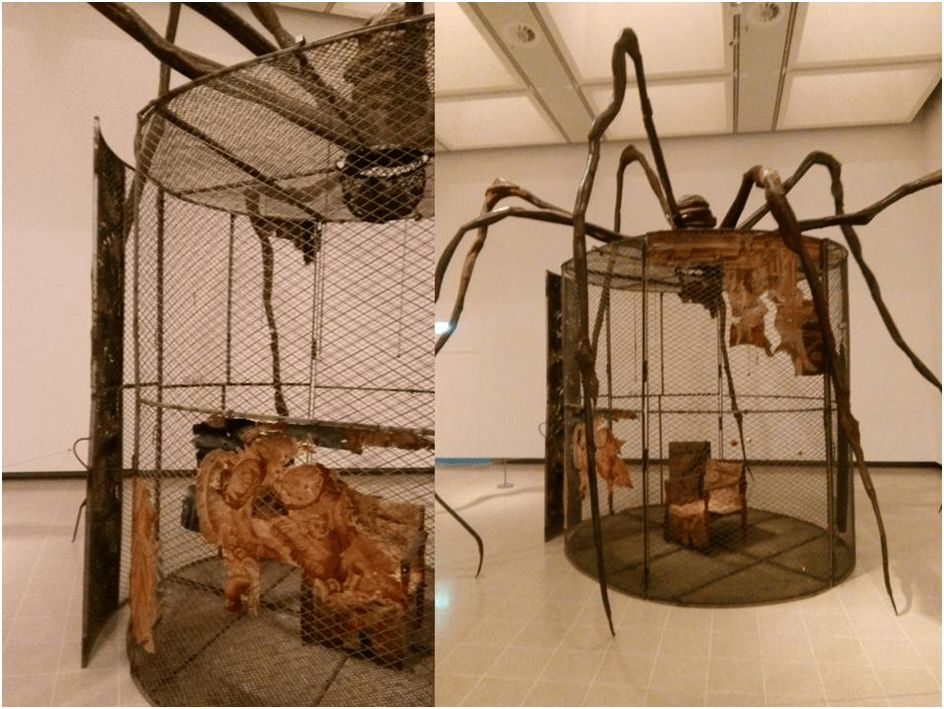

Of course one cannot leave any consideration of this theme nor the show we are looking at, though I have (despite its length) missed out many themes and forms with which this exhibition surprises and teaches us – the fabric busts for instance and ur-tapestries – without looking at the most monumental work, Spider (1997).

This work is used and brings together forms from throughout the artist’s oeuvre, including the metallic spiders she had previously known as Maman. Here is a mother spider with a full egg-sac suspended over a cell she guards and further secures, even if somewhat like a prison cell. Her weaving is represented in the scraps of tapestry work around the mesh of the work, again recalling her parents, and the upholstered chair beneath the egg-sac. The portal to the cell is ajar though visitors may not cross a line surrounding the cell; one is imaginatively invited to enter within. Would such a move feel secure or imprisoning? The issues of Bourgeois’ work lie in the impossibility of solving that question. Lorz points out that on the tapestry on the mesh of the Cell the genitals of a cherub have been snipped out and a fabric phallus suspended within used as a pincushion for exaggerated needles.

If this blog has exhausted anyone patient enough to get this far and thus qualify as a spider in Bourgeois’ understanding, they will know already that I think seeing this exhibition is probably worth more than seeing any other current exhibition in England. This will be so if you know Bourgeois’ work already or require introduction. For there is an integrity to this exhibition which comes from thoughtful retrospect in a way that values the products of a woman in her older age, who yet has more to offer and awaits newer understandings. For if this is not art, nothing is.

All the best

Steve

[1] Louise Bourgeois (LB) cited from 1992 in Ralph Rugoff (Ed., Curator at Hayward Gallery) (2022: 188) Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child London, Hayward Gallery & Berlin, Hatje Cantz Verlag GmbH

[2] Lynne Cooke (2022: 21) ‘Weaving, Materials and Metaphor’ in Rugoff (Ed.) op.cit: 20 – 25.

[3] Julienne Lorz (2022: 35f.) ‘Acts of Reparation: Spiders, Needles, and Cells in the Work of Louise Bourgeois’ in Rugoff (Ed.) Op.cit: 31 – 37.

[4] The reading here in part owes something to discussion by Ralph Rugoff (2022: 14) ‘Mechanisms of Ambiguity and Sensation: The Late Fabric Sculptures of Louise Bourgeois’ in Rugoff (Ed.) op.cit: 10 – 19.

[5] Rugoff op.cit.: 14

[6] Ibid: 17

[7] Cooke op.cit.: 21

[8] Rachel Cusk (2020: 27, 29) ‘The Fabricated Woman’ in Rugoff (Ed): 26 – 31.

[9] See catalogue reference Rugoff (Ed.) op.cit.: 201

[10] Cusk op. cit.: 29

[11] LB cited Lorz op.cit: 37.

[12] Ibid: 33

[13] Ibid: 36 for Lorz quotation

7 thoughts on “FINAL LONDON ART BLOG (5): ‘If I’m in a positive mood I’m interested in joining. If I’m in a negative mood I will cut things’. This blog is really a love song to the art of Louise Bourgeois, so brilliantly curated for the current Hayward Gallery exhibition ‘Louise Bourgeois: The Woven Child’ and the beautiful and brilliant accompanying book edited by Ralph Rugoff.”