‘“Nothing changes. …” /// “…. If they had their way the entire country would be pebble-dashed, …”/ “Who are they?” I asked. / “…The janitors of mediocrity. The custodians of drab … . Men mainly. Where once we built towers to heaven, now we build frumpy sweatboxes for pen-pushers. After nine hundred years I do not call that progress. We’re moving backward, forwards and sideways all at once. We’re oscillating, Robert. …”’.[1] The Offing, a dramatisation of the novel by Benjamin Myers of 2019 at the Stephen Joseph Theatre and the live Theatre, Newcastle. Citations from paperback edition of novel: Myers, B. (2020) The Offing (1st published 2019) London, Bloomsbury Publishing. Paperback ed. as pictured below.

The poet Romy Landau (the German poet in flight from Nazism) in this play, and the novel upon which it is based, is a real person. ‘The Offing’ is her second collection of poems and was published posthumously after the writer drowned at sea off Robin Hood’s Bay. The republication of that volume by UnBound contains a brief biography as a ‘Note to editors’:

Romy Landau was born in Samerberg, Bavaria in 1912. She studied English Literature at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München in Munich and the University of London (now University College London). Her debut poetry collection The Emerald Chandelier (1936) gained international critical acclaim. She disappeared while swimming near Robin Hood’s Bay, North Yorkshire in April 1940, shortly after completing her second collection The Offing, published posthumously in 1947.[2]

Upon these facts (written by Myers too, note), in which her suicide is not confirmed (except as in the play and in his novel as a prediction from one of the poems), Myers The Offing is based. Other details (including major characters) in the novel too are even more definitively fictional – notably her lesbian lover and literary champion Dulcie Piper, who speaks the words cited in my title – in the novel and the play. Dulcie however does represent a type of the literary intellectual of the period – individualistic, anarchic, and angry at the state and institutions that are seen to be as antagonistic to individual liberty by food rationing laws and the like as any other arm of the oppressive state. These characters are angry young people with values that, though libertarian, are far from necessarily progressive politically – if anything more commonly they are rather the reverse. Later in history, such intellectuals (Francis Bacon is an example) would lead the way in condemnation of what they saw as an overgrown state under any form of socialism, except that of the reductive idea from Romanticism of the ‘free’ soul and heart.

Unsurprisingly they are best represented by the memory of Oscar Wilde in the past (cited often in the texts) and Noel Coward in the present represented by the story. In actuality, especially after the War, the examples of such individuals who held a banner for art are nearer to being politically right-wing who called themselves individualists (like John Osborne for instance). But intellectuals indicated by Dulcie Piper were well before the Angry Young Men became prominent (although I oversimplify them here). These earlier figures did also promise rebellion against conformity and bourgeois values that the later men (and Noel Coward) did not – especially in the realm of sexual and queer politics. Such politics are contained in Dulcie’s, if nor Robert’s, concept of ‘poetry’ and what the reading of books should mean: she says; ‘Book are just paper, but they contain revolutions’. Nothing in Robert Appleyard’s later life however will be revolutionary, least of all his sexual politics.

What connects Romy Landau and this representation of an intellectual class from the past is an overtly reductive romantic ideology of the meaning of life based on rejection of class politics and the embrace of a very vague concept in the story, named ‘poetry’ and a strong sense of the value of diversity, represented by the individual person rather than groups or classes of people. Poetry is a very backward looking concept in the novel but is less so in the play because of the wonderful effects that derive from the embodiment of words in persons and of dynamism in their action. Strangely, though I admire the novel, I prefer the play for this reason. This is because in the novel the roots of hope are already dying and dead at the beginning. The novel wants something that is fresh, constant and beautiful to survive but the only candidate for that role is a cognition, a memory and an idea – only these we are told (falsely I believe) ‘never change’. At least, so says the aged hero, Robert Appleyard. The young Robert who starts the story proper at age 16, is described in the novel’s prologue as an idea alone and it is this makes him changeless: ‘But I was a young man once, so young and green, and that can never change. Memory allows me to be young again’. Any 16 year old Psychology student can now tell him that, far from never changing, memories of our youth and ourselves as youths CHANGE all the time, serving all kinds of purposes in our mental self-constructions and discourse. If anything is indicative of the rather loose romanticism of the story it is that. This is not to say, of course, that I personally don’t enjoy and participate in such delusions myself.

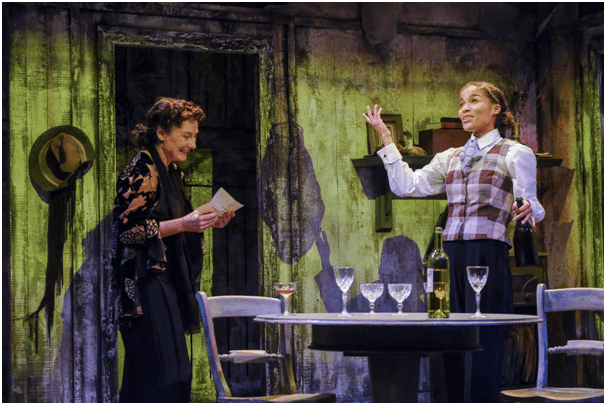

In the play this character is played by the actor, James Gladdon, who has to embody vast changes in represented age on stage; often during the donning or removal of a garment, and does it with the dynamism that understands how cognitions (including social cognitions which I use to indicate hegemonic ideas and ideologies of what aging is) of age shape our bodies through proprioception. In a tweet I expressed my admiration thus: ‘When he metamorphosises, as he does from old to young man and vice versa, his whole body enacts the transition. It is inspiring to see’.[3] The very fact that such transitions and changes can be enacted in the body is a critique of the static romanticism so lauded by the older Appleyard in Myers’ novel, I believe. It allows us to escape the death-centred ideology of the novel’s romanticism, so locked as it is in a myth spun around Romy Landau and the central image and cognition of ‘offing’.

Benjamin Myers is a good writer and the qualities of the prose I describe above as ‘romantic’ I attribute not to his own character and persona (for writers often choose to elude our grasp – and Myers is one of these) but the fictional autobiographer who narrates the story, Appleyard. In my opinion the book is death-centred because, despite all efforts otherwise to keep moving backward to his youth, he is as death-centred as is Romy Landau, as unhealthily unable to take note of the contemporary and move it forward to a changed future that extends beyond selfish concerns, preferring as he ends the epilogue to ‘cling to poetry as I cling to life’.[4] And ‘poetry’ is what Dulcie stands for too, although for her it is something entirely sexualised in order to be dynamic, like the writing of D.H. Lawrence, rather than the ‘Georgian’ purple prose Myers gets Appleyard to pen or type.

Strangely enough however detractors of the play, which do not include Myers himself, think that it is this very quality of the prose – which one critic (Mark Fisher) calls bucolic, whilst using the descriptor rather inaccurately – that renders the play unworthy. But the truth is far from this, in my view. As played by Gladdon, the rather escapist qualities of Appleyard come to the fore. In fact, Myers (who knows his stuff) deliberately characterises Appleyard as an Angry Young Man, who appears to even his contemporaries a ‘rebel’ (as Landau and Dulcie in some degree definitely are) but is in fact just accepting the ‘accolades’ and cashing ‘the cheques’. His whole soul is locked in the language of the market: ‘Youth had recently become a commodity to market and apparently I was one of the voices that captured it – a spokesperson for the young and disenfranchised. {my italics}’ But that was because: ‘Time was on my side then’. Now, as he decays with the system of he is aware of time as ‘this thing that eats away inside of me: a disease called time’.[5]

I hope this characterisation of Myers’ shows him as a rather more thinking writer than he is sometimes represented to be – liked for for his ‘lyricism or ‘bucolic’ quality’. The style of the writing here I see as part of the flesh of the writer Appleyard (who is so perfectly ‘the word made flesh’ by the artist that is Myers). This seems to be why Mark Fisher has no chance of truly appreciating this play in his Guardian review of its outing in the Stephen Joseph theatre at Scarborough since he just simply likes the prose-style of the novel rather than thinking about it. The writing in the following excerpt from his review shows a lack of understanding of novel-writing as deep as that of acting, directing and setting a contemporary play to qualities of theme – including the need to make evident the effects of time in significant ways in each of these arenas.

Stripped of the book’s rich language, stripped even of its outdoor settings by Helen Goddard’s fussy interior set of weather-worn wood, The Offing loses many of the qualities that make it compelling. Dulcie is less extraordinary, Robert’s coming of age is less extreme, and Romy is at once too present and too little fleshed out to make us care.[6]

Maybe we do not need to be fair to actors, but this piece really does harm to actors who each realise ideas in the play and book, sometimes more clearly than does a book when readers fail to notice that you cannot talk about a book’s stylistic characteristics without also looking to the dramatic and narrative elements involved in, say, a concept like ‘the unreliable narrator’. For the character Appleyard is precisely shaped as an ‘unreliable narrator’: Myers knows his Henry James well enough to do this well. Appleyard is a man who escapes pit-life in County Durham and makes himself a rich and, for a time, famous man. But I don’t think he is the ideal Dulcie sees in him, nor is he a romantic who will not compromise like Romy; who would rather die than do so.

The quotation from the title is Dulcie’s summation of the contradictions of the modern city of Durham, used to show that ‘time’ is not progressive, using the example of that city’s wonderful Romanesque cathedral in contrast to its then terrible post-war civic buildings. But what it misses is a perspective Robert knows better than her – the life of the Durham mining villages. For bohemians like Dulcie ‘Silence’ is not only ‘golden’ but about knowing of your self- including the motion of your blood, as in most romantics.[7] However silence for Appleyard is about not speaking the truth of the terror that marks the oppressions of mining lives in the Northern coalfields. Appleyard learns that the mining communities take on the mask of silence on seeing their own oppression in order to lie low and fit in to the status quo. At least this is how I read this enigmatic passage wherein Robert refuses an opinion on whether one shouldn’t speak out the truth, as required of herself by Dulcie, rather than prevaricate and serve the time:

Again I wasn’t sure what I thought so I just nodded, and thought about how so many people I knew back in the village preferred to say nothing than suffer the embarrassment of speaking the truth. Only in these passive silences was truth to be found.[8]

For time must for Robert be used as a means to survive at all costs, even to accepting lies and living in the reserve of a masturbatory past, consumed in inaction – political or sexual, where romantic desire produces only the feeling in his skin of the after-effects of a wet dream; ‘itching, sweaty and encrusted to the coarse wool of my blankets’ [my italics will help you to savour the brilliance of that word ‘encrusted’]. Such effects are difficult to enact in a play but it is precisely for this reason, I take it, that the play used the character of Romy unlike the novel, and to the distaste of Mark Fisher in The Guardian, as the complex symbol she is for different characters – first, as the romantic rebel against convention as seen by Dulcie, and, second, as a symbol of the oncoming need to possess a virgin sexually for Robert. This is why, I take it, the play adds a sequence that is not in the novel (explaining Romy’s penchant for hiding things as a game ostensibly) of an exchange of rings that cause interaction between Robert and Dulcie. It is also why both in the novel and play, Romy must take on, at some level, the meaning of the ‘wasted’ virgin that haunts it – in the novel only this happens first in the scene in the Robin Hoods Bay village church but in both novel and play it occurs in dramatic and theatrical debate between Dulcie and Robert in which the symbol of the ‘maiden’s (virgins) garland’ matters: ‘They’re placed on the heads of those who are purported to have died chaste’, like Ophelia in Hamlet, Dulcie says.[9] But the key word here is purported. In my view Robert continually represses the lesbian relationship and the sex this might involve in order to use Romy as his own symbol of the sexual availability of women, which like Romy’s photograph, he ‘found exciting’.[10]

These elements are in the novel shown through episodes showing Robert’s sexual adventures with young women and girls he meets on his wanderings but never names. For obvious reasons of scenic economy, they could not really be shown in the drama of a play. People will differ in their interpretation of Gladdon’s representation of the night terrors he enacts. But I see here a consummate actor showing Appleyard’s complex and rather subliminal sexual birth as a ‘woman’s man’ in the shadow of Romy’s allusive and alluring ghost, however obscure their embodied meaning will always be (as non-verbal body language must necessarily be since all its signs have many possible meanings in whatever context). Watchers like Fisher, of course, will never get it and will blame the direction or the acting of the cast, especially the female actors – quite unfairly in my opinion when he says: ‘Dulcie is less extraordinary, Robert’s coming of age is less extreme, and Romy is at once too present and too little fleshed out to make us care’. Take no notice cast. It is a case of ‘pearls before swine’ (LOL).

Ron Simpson in The Reviews Hub, whilst making nothing of his truer description of the enacted achievement, is more correct about the performance of the actor playing Romy than Fisher, even though he is equally stymied by a wish to believe the novel HAS to be greater than the adaption: ‘Ingvild Lakou appears first as a dream or a ghost, but takes glamorous and tempestuous flesh and blood in a couple of flash-back scenes’.[11] A dream and ghost in fact, I believe and this is what makes Romy a really difficult role to perform and involved producing a kind of difference between, on the one hand, the enacted verbal sequences – being memories of her lover by Dulcie – and, on the other, those more like modern dance – ritualising symbolically Robert’s heterosexual fantasies. As a result this actor has received unfair criticism. Her performance in both avatars of Romy was, in my opinion, flawless. Robert snatching D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover from Dulcie only when he realised it had graphic heterosexual sex scenes was one aspect of this subtlety of interpretation in this novel. For instance although Dulcie gets that Lawrence was in fact sexually ambivalent, he seems not to hear: ‘The only thing Bert ever spied on was shirtless farmhands and cuckoos’ nests’. What angry young Appleyard becomes is someone more like the John Osborne generation rather than the subtler and more embodied queer sexuality of the Lawrence generation that Dulcie represents to us radically in herself and them, for instance in her and Romy’s fear of fascism: ‘There would be no room for the poets or the peacocks, the artists or the queens’.[12] It is the queer in Dulcie that Robert continually avoids. I remembers fondly from the play the moment when she suggests Robert will have a girlfriend later – or ‘a boyfriend. Or both’. It is a queer potential Appleyard does not forefront in his writing.

For his supposed lyricism and bucolic nature is actually a ‘poetry’ (not of life and love, as Dulcie says Romy’s is) but of repression, equivalent to the drowning of Romy. Here is a typical example: ‘Night settled upon the meadow like a trawler’s net sinking slowly to the deeper waters, the sun fading as the gloom enfolded everything within it’.[13] The important thing for Appleyard is neither poetry nor love and justice but survival over time. The threat of not surviving is symbolised in the drowning of Dulcie, pulled under by the ‘undertow’ of the sea, as in her poem ‘Exeunt’:

A snuffed-out sun, the retreating shore. The perfect undertow seeing her home.[14]

Whilst Dulcie embraces the current that will take her under the water rather than survive in a world of utter convention, this will never happen to Appleyard, who will not be seen ‘home’, in Durham for instance, till he gets an administrative and not mining job. Home will get nearer and in a changed form when he later accepts Dulcie’s help to get an education denied his peers in the Durham mining villages. He sees the ‘structure’ in which he will live and write, and in which Romy once lived and wrote, and he describes it precisely as surrounded by dangers that are described precisely as an ‘undertow’. But unlike Romy who walks into watery death, these dangers he must and will avoid. He will neither be pulled under by suicide, ‘sunken’ by standing outside of norms as Dulcie and Romy did (by being sent down ‘under’ ground for instance to the mines) as seemed his heritage.

Walking back, I saw tucked away in the top corner of Dulcie Piper’s meadow, adjacent to her house and secreted beneath an overhang of branches, a sunken structure which, like the cottage, gave the impression of being pulled under.[15]

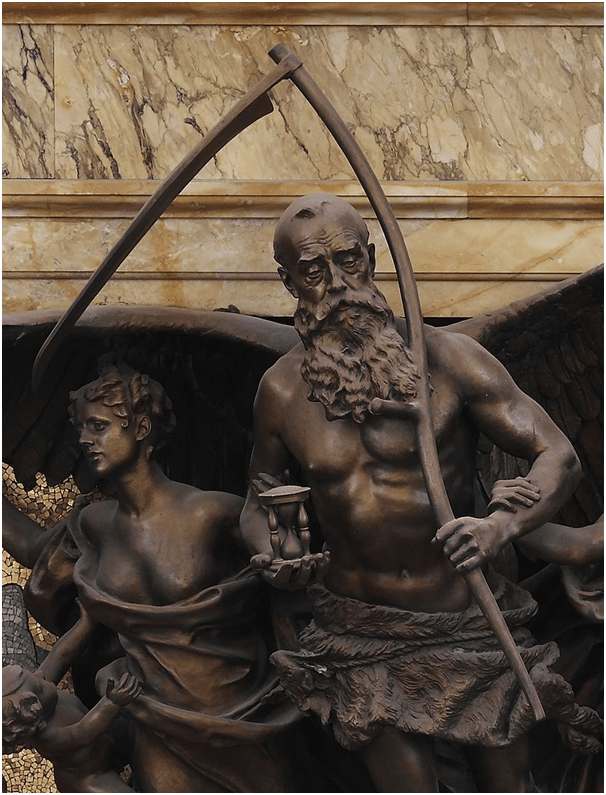

This is a difficult issue to enact. This novel in my view is a fictional autobiography of a writer very like David Copperfield. But it is a writer who is not, and not like, Benjamin Myers though both come from County Durham. But this play is a beautiful wonder, which is very well cast, set theatrically and produced or directed to emphasise responses to passing time – even in enacting age change forward and backward. In that sense, it does more than many plays I have seen enacted and more subtly, for the nature of time is the most important themes of any art, including drama. The worn set and its lighting is about imaging time as decay and possible renewal. Most subtly it lies in the iconic picture of Robert holding a scythe and enacting the icon of Time as the mower in slow motion centre stage. For if Robert brings about change over time, he also holds back and contains time in the manner of all political conservatives; however apparently passive and inert he seems at heart.

But the dialogue also shows time’s process continually in which manipulations of the enacted body is its magic reversals and inevitable continuations. We see that here, in this apparently simple exchange:

‘You should eat.’

‘What time is it?’

‘There you are with time again. …’[16]

But time passes indeed. You have only until the 27th November to see The Offing at the Live Theatre at Newcastle. Let it pass and you’ll regret it. You really will.

All the best

Steve

[1] Myers (2020: 158f.) The Offing (1st published 2019) London, Bloomsbury Publishing. Paperback ed. as pictured.

[2] Benjamin Myers own blog ‘The Offing by Romy Landau’ available at: The Offing by Romy Landau – Benjamin Myers (wordpress.com)

[3] Steven Douglas Bamlett on Twitter: “Follow James. He is wonderful in ,’The Offing’ at @LiveTheatre . When he metamorphosises, as he does from old to young man and vice versa, his whole body enacts the transition. It is inspiring to see. Loved him in the role.” / Twitter

[4] Myers op.cit.: 3

[5] All quotations from ibid: 256f.[6]Mark Fisher (2021) ‘The Offing (review) – soft pedalled adaptation of Benjamin Myers’ novel’ in The Guardian (online) [Fri 22 Oct 2021 11.32 BST] Available at: The Offing review – soft-pedalled adaptation of Benjamin Myers novel | Theatre | The Guardian

[7] Myers op.cit.: 69.

[8] Ibid: 116.

[9] Ibid: 146f.

[10] Ibid: 153

[11] Ron Simpson (2021) ‘The Offing: Review’ in The Reviews Hub (online) [Monday November 8th 2021]. Available at: The Offing – Stephen Joseph Theatre, Scarborough – The Reviews Hub

[12] Ibid: 77

[13] Ibid: 61

[14] Cited ibid: 164.

[15] Ibid: 47.

[16] Ibid: 79.

4 thoughts on “‘“Nothing changes. …” Reflecting on ‘The Offing’, a dramatisation of the novel by Benjamin Myers of 2019 at the Stephen Joseph Theatre and the Live Theatre, Newcastle. Citations from paperback edition of novel: Myers, B. (2020) ‘The Offing’.”