‘… the importance of rescuing the defeated, the silenced and the dispossessed from the “enormous condescension of posterity”’.[1] This is a blog on reading local histories in the context of modern constructions of global economics. It tries to understand what is added to understanding the complexities behind terms like ‘class’ and ‘community’ in contemporary political contexts in Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson’s (2021) ‘The Shadow of the Mine: Coal and the End of Industrial Britain’ London and New York, Verso Books.

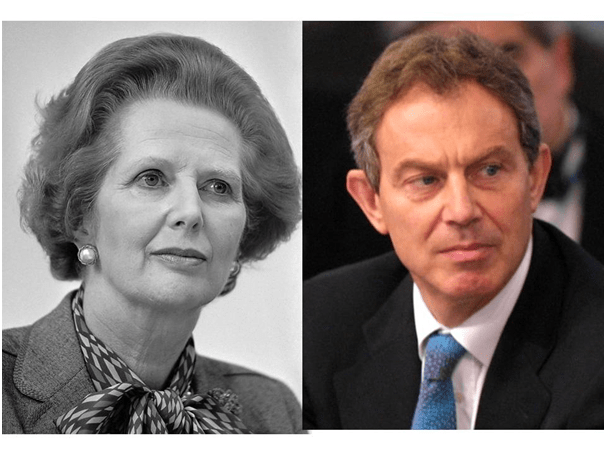

Edward Thompson tells us more about why we ‘do history’ in just naming the default attitude of the present to the past as the ‘enormous condescension of posterity’: it is not only that our ancestors, even our parents seem to be so much less sophisticated than ourselves but they are simpler and lack our insight and foresight; are locked in their own time and its undeveloped tastes and manners. This is most telling when we consider the terms like ‘community’ and ‘class’ through which all of us, as groups rather than individuals, live out our history and histories. For some these concepts can only be meaningful in simpler less sophisticated contexts than those of the present. The implicit narrative of much contemporary commentary is that ‘class’ is no longer a viable concept in either social or economic terms (a person’s primary relation that is, in the latter term, to the ‘means of production’). These are often concepts that get relegated to features of an ‘industrial age’ – in which economic production was more localised and concentrated geographically and not as subject to the plasticity, mobility and instability we demand now as a right of our freedom. Plasticity, mobility and instability are required as components of an ever-changing set of configurations that spring from global capitalism (often known merely as globalism) that became the dominant force of modernity in the political ideology that Beynon and Hudson, with others after Simon Jenkins, call ‘Blatcherism’.[2]

These authors summarise Blair’s inherited economic framework, as delivered to the Confederation of British Industry (CBI) in 2000, which involved a passive response before ‘the vast new opportunities but also massive insecurity’ involved in working life. Labour policy needed to adapt its values, Blair outlined:

… as both an essential requirement for and an unavoidable consequence of globalisation and something which confirmed the new portability of ‘work’ and the increasing transient nature of working relationships.[3]

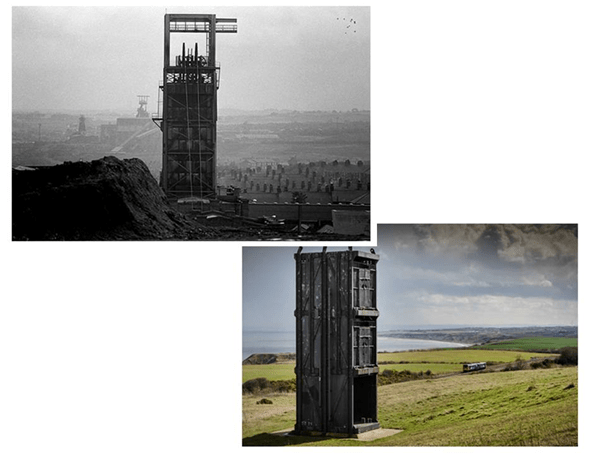

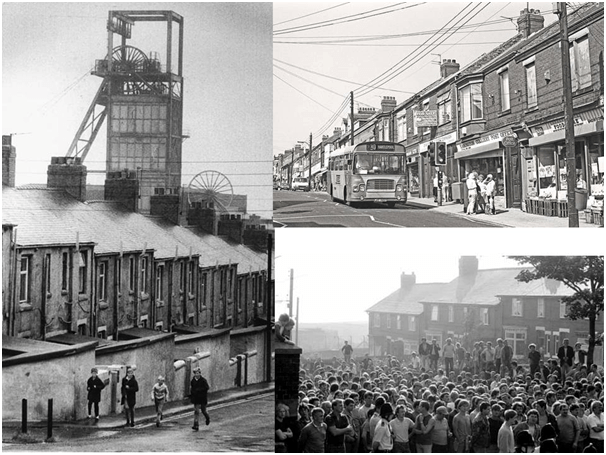

In this context both class and community must be subject to, and become objects of, socio-economic policy determined by a force though to be independent of them, the ‘market’. In industrial terms both were indivisible too from the social institutions and its architecture and geography of a place. Look for instance at this comparison of scenes:

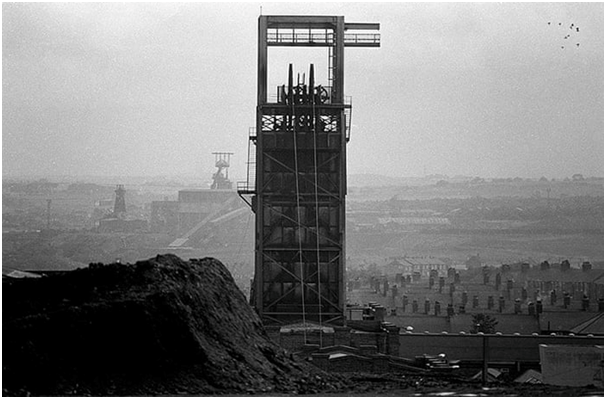

Even taking in the difference of perspective on the main architectural feature – the shaft that held the huge cage carrying the miners of Easington Colliery beneath the ground – the pictures show a coastline whose function has complexly changed. In the second the coast is almost empty in appearance: the sense of a dehumanised landscape is created by a world in which not only work has gone but the workers and all the products, and even the ugly by-products of their work, have gone. Look more closely at the first picture, which appears in the book, because what we see is the marks on the landscape that indicated a class and several separate communities: Easington Colliery, Horden and Blackhall.

Easington Colliery lies above the coastal plain which are themselves above the cliffs to the beach. That beach was once a repository for mining waste. Further above the pit area is the village that is also called Easington Colliery (to distinguish it from Easington Village) yet further above again. The village was populated by miners in houses lying in a grid pattern and the grandiose architecture of the Welfare Halls and administration buildings of the Durham Miners’ unions and associations. Its spaces were filled during the Miners’ Strike in the 1980s by people, set against masses of police organised against them, who both lived and worked in the pit since these coastal collieries called in workers from across Durham, many displaced from mines that closed because they could not be worked because exhausted, or more recently many that were dubbed ‘uneconomic’ by the standards of a now globalised market. Below we see what a ‘communit’ looked like in the public eye – though that eye tended to concentrate on the working men only. It is a community defined by the illusion of the permanence of work – work that your father did and which, if you were a boy, you would do too. In doing so, you would reproduce values that were increasingly coming to seem embattled and which in the 1980s were embattled and after that, during the period of Labour government and after, enacting defeat in which community ‘leaders’ colluded.

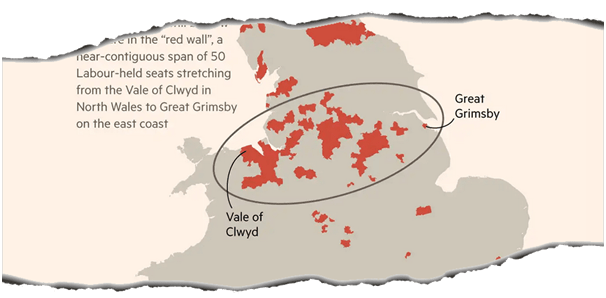

These complex shifts are the stuff analysed in this book through the comparisons between the mining areas of South Wales and the Durham Coalfield. It is a story in which labour politics in its different appearances had a big effect on the future. The collusion of the Labour council and the Durham Miners’ Association are in part shown to us in order in part to show why the predominance of Labour in Durham, insultingly called the Red Wall,, was lost to a hopelessness that found more sense of identity with Brexit than a party seen, it is asserted, to favour middle-class values and the values of a European administrative class rather than of a ‘British’ working class. These questions remain as complex after you have finished the book as when you started it. In Durham the more dramatic shift is attributed to issues like the local council’s antagonism against regenerative strategies based on the development of male sports like boxing, which Labour councillors thought, according to Mary Stafford, an activist from the Miners’ Strike organisation of Women, ‘a dangerous sport, not the right thing and not to be encouraged’.[4]

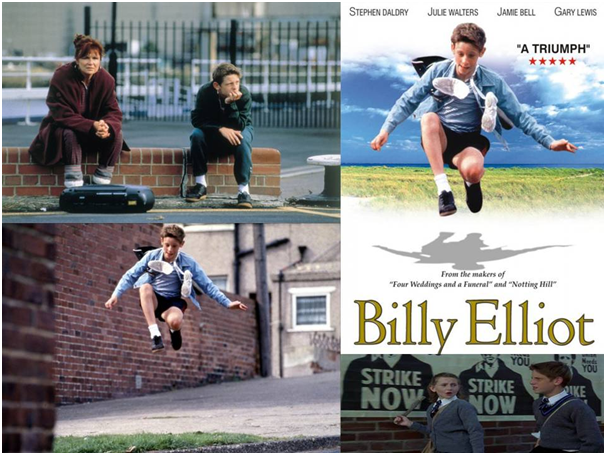

People will recognise a culturally metamorphosed version of these contrasts (of the deeply engrained masculinity of a traditional culture and a free and flexible culture in which boys feel free to move to London, gain a middle-class education and ‘dance’) in the film of Billy Elliot. Sometimes the part of Lee Hall claims to be the same party as that of Miners’ Workers but the contradictions did seem to fly apart when the ‘Red Wall’ fell.

I think some idea of how this was reflected culturally might be gained by seeing how the scene in which Billy’s dance reaches literal heights with an image of him hanging in the air above Easington Colliery streets. In the poster for Billy Elliot for mass release, the image of Billy raised in the air is retained but the streets in which the community live are gone (replaced by green landscape and blue sky). What also is not shown in the advertising is the link of the film to the Miners’ Strike which appears briefly in the film to show the violence associated with Billy’s brother and father. Julie Walters – playing a teacher of dance – rescues Billy from a boxing class in which he did not excel or even cope and from his father and brother’s slimmer life prospects.

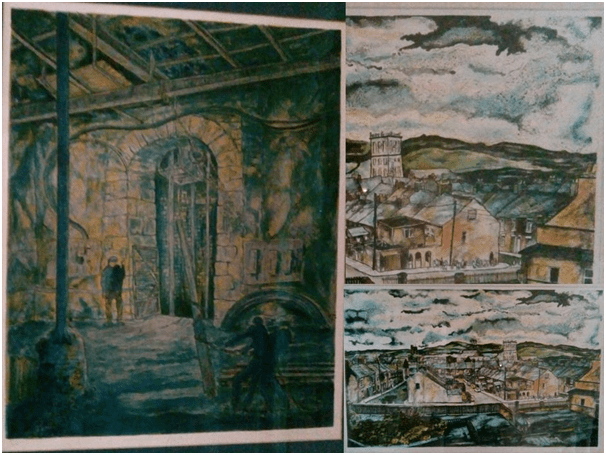

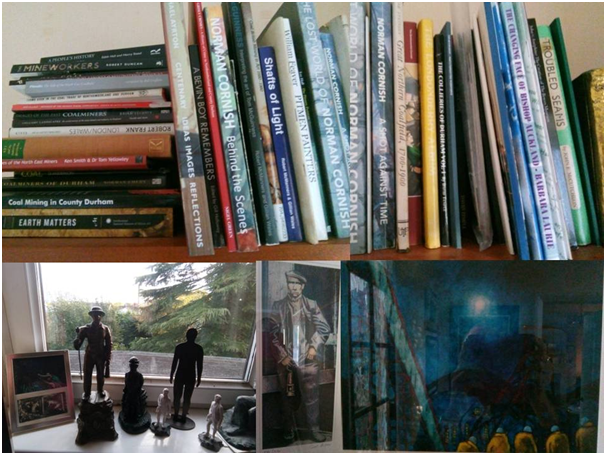

As I read this book I relive my own complex contradictions between a socialism attached to the class of my parents, which in all truth I have left behind by being the first in my family to be university educated and to have had a career that was largely in middle-class occupations. Those contradiction owe something to the instabilities of my own mental health caused various shifts up and down the occupational ladder of class – being, for instance, for one period, a night worker in a mental health residential home on £1.10 per hour (before minimum wage of course). They owe even more to my commitment to the arts and literature and the distance this has created from the elements of working class mass culture that was all I knew in my childhood. When I moved to Durham from London with my husband Geoff in the 1990s I slowly but gradually began to identify with Durham mining traditions and images of their working class from which I nevertheless felt alienated by my sexuality and interest in the arts. For me this led to an interest in mining and mining art, something some will see as middle-class appropriation of another culture. The pictures below show the extent of how these interests are reflected in items in our home: (i) some images of Easington District, Durham (from my limited lithographs of Tom McGuiness’ ‘A Nature Walk’ [a landscape of Murton near Seaham] and ‘The Pantry’ [the storage room of heavy plant at Easington Colliery] and (ii) my books and ornaments with mining figures and themes.

However, to me, although I admit there are aspects of cultural appropriation in this behaviour, there is also an attempt to heal a fragmentation in me which came with middle-class identity following after university and taking my first job as a Lecturer in English that was compounded by me not having an inherited or assimilated bourgeois culture to sustain it. Instead I think I look for a culture with which to identify than that of my original one from West Yorkshire and from the cusp of the working class – a self-employed father in manual service work and somewhat remote from the mass of industrial work and a grammar school education and the experience of growing up queer without support which alienated me eventually from both parents, somewhat painfully. Now I do not say this in a spirit of suffering or specialness but to show that the contradictions that can often take these forms in many socialists – adherence to mass industrial values, including those of a community, which may (but not necessarily) be hostile to them individually, and a belief in individualistic and non-communitarian identities.

Moreover, any examination of the softer and non-ideological data, that expresses the feelings of miners, is of a community in which the iconic masculine function of the role was always as much in question as an element in the political oppression and shaping of the miner’s subjectivity as the difficulty of his work. This can be found in the novels of Sid Chaplin and the paintings of Norman Cornish and Tom McGuiness in the Durham district, and the work of the Spennymoor workers educational organisations. In my view community and class are already complex and non-monolithic concepts with softer and fuzzier margins in these places than is often represented, a place where Lee Hall’s experience and that of Billy Elliott’s brother are closer than we think.

I do not know the answer to such contradictions but they continue in modern left socialism – though the soft right of Labour that once controlled Durham labour organisations seems now to be in hegemony in the Party. I hope this is for a short time, because it represents no values at all. This was perhaps always the case. For instance, in the era of expansion of production of coal after the war, the book records the undemocratic collusion of local Labour Party leaders and Durham NUM with the deliberate suppression of the availability of non-mining jobs and roles that might have diversified employment for the future and with the Labour Government’s plan for the decline of coal over support for local jobs that started under Harold Wilson’s ‘white heat of technology’ revolution.[5] It is worth reading the book alone to see how the authors argue that the loss of the Red Wall in the seats such as North West Durham, the seat I and my husband live in and fought for Labour for, had much more to do with this history of actual exclusion from participation of power of the working classes as a class, however unintended. It rang bells with what I heard on the Mown Meadows Council estate (‘Labour is trying to steal OUR Brexit).[6] That I, and my husband, were Remainers, lived in private housing and were openly queer seemed part of the issue here.

My own response is NOT now to be in the Labour Party but to seek a new reconfiguration of politics through proportional representation and by focused issue-led campaigning. I do not trust monolithic compromise and drawing up policy in secret conclave. I love this book. It tells how, once, Labour Leaders would sometimes visit meetings in Crook, the small ex-mining town in which I live (but now a place of rural near-moorland beauty). It is a tremendous book.

Read it, please. It is a very stimulating book for all kinds of reasons and really well written.

All the best

Steve

[1] The cited quotation is from Edward Thompson (E. P, Thompson), the activist socialist historian of labour in Huw Beynon and Ray Hudson (2021: 6) The Shadow of the Mine: Coal and the End of Industrial Britain London and New York, Verso Books.

[2] Ibid: 203

[3] Ibid; 317

[4] Cited ibid: 332

[5] Ibid: 53

[6] Ibid: 329ff.

Thanks for the good critique. Me and my cousin were just preparing to do some research on this. We got a book from our local library but I think I’ve learned more from this post. I’m very glad to see such great information being shared freely out there…

LikeLike

Great comment, I really like this blog and will bookmark it. Keep up the good posts and articles

LikeLike

I discovered your site web site on bing and check many of your early posts. Maintain up the really good operate. I just additional your Feed to my MSN News Reader. Looking for forward to reading a lot more from you finding out later on!…

LikeLike