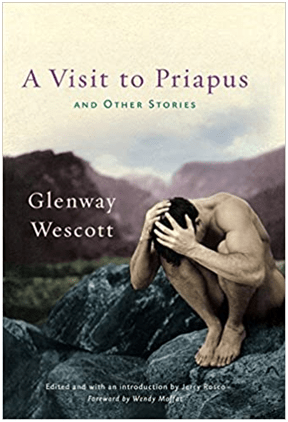

‘Does size matter?’ And other questions raised by the lack of cognitive scripts in genderqueer queer lives: Why we need to look again at a lost queer American novelist – Glenway Wescott, with a focus on the then unpublished story A Visit to Priapus in Wescott, G. (ed. Jerry Rosco with Wendy Moffat foreword) A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories (2013) Madison & London, The University of Wisconsin Press.

My title of course presumes a lot that cannot be presumed or assumed. It is based on a belief of mine that I don’t want to argue here. It is that the consequence of the lack of a public discourse of queer sexuality that addresses lived queer experience (that experience not described by socially or institutionally validated norms) is a lack also of adequate cognitive scripts (or schemas– choose your jargon) for the performance of sexual acts and/or reflection.[1] The marginalisation of what is queer is in a sense already implicit in the definition and recognition of queerness (not just in sexual terms of course, and certainly not just in terms of LGBTQI+ issues though it includes these). It includes the ways too in which queer behaviours or ontologies (definitions of what is deemed to exist in reality) are appropriated by normative discourses and translated into the language of the latter. This is also how queerness becomes, In Paolo Freire’s terminology, the object also of public discourses in social policy, politics, the law and a supposed objectivity in academic research rather than a subject who speaks of its own experience. Unsurprisingly, in these discourses, that which constitutes queer sexual ontology or behaviour tends to be described in negative terms and as that that is considered appropriate and acceptable. We see this in the hush over public discussion of issues in these areas of experience or that’s discussion’s limitation to stereotyped questions and answers, as the Kinsey researchers often found in dealing with Glenway Wescott (who was a ‘subject’ and recruiter of ‘subjects’ thought to be queer for Kinsey and a personal friend of the latter).

These processes of marginalisation and negative transcription have a real effect on queer lives, especially in the process of growth, maturation and the definition of adult life models for behaviour (including appearance) and ways of being in the world in young queer people. In the following, however, I will largely confine myself to literature, which is both a normative discourse of a society and a means through which those normative discourses become adapted or even deconstructed. I will moreover confine myself to the gay male end of the genderqueer spectrum, though that too limitation depends on an enforced script for the meaning of sexuality comprehensively understood (a puzzle I am not going to explore here).

The classic early male gay novels (published or unpublished such as Rodney Garland’s The Heart in Exile (the link is to my blog on this issue) and E.M. Forster’s Maurice (written 1914 but not published then)) do little to challenge the authorised heteronormative discourses although both do something. Indeed the challenge often arises from novels on the cusp of queer male identification (such as those by the now unjustly forgotten Ernest Frost (use the link to see my blog) and (still better known at least in the United States, but not necessarily as a queer novelist) Glenway Wescott, on whom I will concentrate. Wescott had influence in his time not only in the United States but in Britain, through his association with the ‘Crichel Boys’.

First of all allow me to justify why I look particularly at the issue of penis size in male gay discourse, at least as reflected in the novel in the USA after the influence of Glenway Wescott, once thought a possible equal to F. Scott Fitzgerald and Ernest Hemingway, in the period of the Violet Quill (Edmund White, Felice Picano and Andrew Holleran being the best known) group of gay male authors, about whom I have blogged twice. In these books a discourse about penis size is central, as critics have often pointed out and below, I quote from one of my blogs (one on Holleran’s The Dancer from The Dance) on those writers rather than summarise it. In this piece I elaborate on the theme that made Holleran describe, if only by comparison to later less focused queer male writers (focused at least on queer males only) ‘dick lit’ before going to say the book has other fish to fry – ones relating to the definition of art itself. It starts by returning to the title quotation which speaks of:

… a ‘small penis’ as ‘the leprosy of homosexuals’. There is a later example in a list of ‘circuit queens’ who frequent the bath houses which includes the deliciously named ‘Randy Renfrew (whose penis was so small no one would go to bed with him)’.[10] Of course penis size is one of many features that I want to call superficial, but which I can’t because their essential attractiveness is probably imprinted in a queer man of my age and history. These corresponding features are described in the story of how Malone decided to improve the look of his body: ‘For if anything is prized in the homosexual subculture than a handsome face, or a large cock, it is the well-defined athletic body’.[11] Elsewhere the narrator quotes Sutherland saying that there ‘were only two requirements for social success with those queens ….: a perfect knowledge of French and a big dick’.[12]

There is no doubt that the ubiquity of the standard set by penis size was understood by other Violet Quill readers and writers. By 1985 George Whitmore could makes the concentration on male sexual equipment almost a means of exposing the emptiness of male relationship focused solely on this. In an important sexual encounter in The Confessions of Danny Slocum analysed by David Bergman, the eponymous hero, Danny, describes his lover as holding Danny’s ‘cock in his soft brown hand – like the gearshift on a car’. Bergman says this passage turns the penis into to ‘an implement for controlling an energy that is directed elsewhere, a mechanical instrument that is manipulated but not enjoyed’.[13] In the same novel Danny reveals he has read Dancer from the Dance, taking from that experience a lesson based on the very passage I have used in my title: ‘I’m reading this new novel in which a character says that men with small cocks are the lepers of the gay world’.[14] At this point I feel that queer writers and readers, of which I am one of the latter, need to examine carefully how representations of gay men by themselves in terms of this standard of human value stand in terms of our wish to see ourselves represented. …[2]

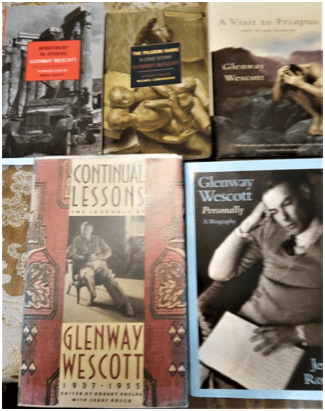

Since I published that blog out I have done some of that reflection but only as aided by reading some biography and some of the oeuvre of Glenway Wescott, at least those books which followed his identification as a recorder of the family life of rural Wisconsin. Here is a picture of what I read to save naming them. I think my reflections then inadequate. The fact that I see the issue as a problem for queer men and of their making is I think totally fallacious (or even ‘phallacious’ (sic.) – never could resist that old joke).

Wescott’s published fiction rarely confronts ‘homosexual’ or queer sexualities openly, though the sexualities that are in the novels are ‘queer’ by any definition and are queerly expressed stylistically. This is so even in the heterosexual married couples in The Pilgrim Hawk (1940). For instance, the female hawk in it is sometimes allowed to associate symbolically with male appetitive desire. We are that that her expression:

… was like a little flame … it did not flicker and there was nothing bright about it nor any warmth in it. It is a look that men sometimes have, men of great energy, whose appetite or vocation has kept them absorbed all their lives.[3]

This is typical of the strange associations in Wescott’s work – between the desire to follow a vocation, such as an artist’s, or appetite, such as sex, though ostensibly this section is about ‘hunger’ of a more meaty kind. Nevertheless this ‘little flame’ is one way, perhaps the only way sexual desire is treated in the novel. Within a few pages, the unmarried narrator, the same one in A Visit to Priapus, where he is predominantly seen as having desire for other men. The narrator makes the link to sexual urge coyly but definitely: ‘I began to think of her as an image of amorous desire instead’. And if unable to get her prey let ‘themselves die’ of unsatisfied hunger.[4] It is not long before he makes the same point but now confining himself to attending to only human male ‘amorous desire’ and deliberately naming it as sex, where the same problematic, and almost subjective, associations between love and sex, male and female and the vocation of art and sexual desire are continually confused together:

No doubt art is too exceptional to be worth talking about; but sex is not. At least in good countries such as France and the United States during prosperous periods like the twenties, it must be the keenest of all appetites for a majority of men most of their lives.

And highly sexed men, unless they give in and get married and stay married, more or less starve to death. … The old bachelor is like an old hawk.[5]

We are in virgin territory here for literary criticism but I find it fascinating that the analogy between the desire to create art and have sex is made so openly. There are no ‘scripts’ or ‘schemas’ for such associations in normative discourses. Wescott is ploughing new ground on the basis of an intense subjective self-analysis and even the most open-minded reader must admit to a sense that something quite different, and perhaps apparently inappropriate, is going on in the associative symbolism of this novel in the exploration of marriage and long term sexual-and-love partnerships. Even the axiomatic level of discourse says this: ‘of course true love and lust are not the same, neither are they inseparable, nor indistinguishable. Only they reflect and imitate and elucidate each other’.[6]

Perhaps, if you find this interesting you will also agree that Apartment in Athens (1944), which also investigates a heterosexual marriage in these terms, is a much under-rated and very queer novel. I will, however, confine my citation of it to just part of the introduction of the Helianos marriage, whose strangely metamorphosing sexual-cum-domestic life is disrupted by German Fascist invasion and the forced lodging in their home of a military man.

… It was the autumn of their love no longer, but suddenly winter, when in fact, with illness and starvation and decrepitude, the coldest of husbands and the bitterest wives often do find each other kinder than nature, kinder than God.

To be sure there was nothing erotic or sensual or even sensuous about it. Helianos was, or fancied that he was, impotent; and Mrs Helianos’ menopause had come early, in keeping with her poor health in general. Yet in the dead of night they pursued an extraordinary intimacy, as they lay wearily in a heap of one body almost on top the other on the folding cot. They knew once more the double egocentricity of lovers, confusion of two in one. …’.[7]

Perhaps many readers will find this incomprehensible, perhaps even not worth comprehending, but it is typical of Wescott as he builds analogies between his own experience (in a relationship between three co-resident men) where the nature of the need for love and sex are continually engaged with and something generalisable (if decidedly queer because not talked about) from everyone’s everyday experience of relationships. And this quality of talking outside the patterned expectations of norms (the reality of cognitive schemas and scripts) is what I find most compelling (and almost unique) in Glenway Wescott, and why I believe that his neglect is so to be lamented and his stereotyping on the basis of his sexuality, alongside other openly non-normative men, by Ernest Hemingway (a very closeted non-normative man) so parlous.[8] He asked questions. He tells in an incident that can be interpreted to show that researchers who worked for Alfred Kinsey thought like this too, although they were people who were not easily shocked, they spoke of some subjects in coded language to try and appear to fit in with appropriate kinds of social behaviour:

They got so shocked by me every time I opened my mouth. Everyone would listen to me. And I said, ‘Now look, I never talk about the research in the restaurant. I only talk about myself.’ Kinsey said, ‘But you know, it makes a scandal for us just to be seen with anyone as candid as you are!’ Little by little I learned.”[9]

Westcott’s openness to subjects often marginalised or censored means that the kind of chat about sex that seems sociologically typical of the groups of queer men favoured by the Purple Quill writers, in Wescott, much earlier in history, seems conducted in a much more questioning and reflective way. This is true of Wescott’s treatment of themes like the distinction between in interacting phenomena like love and sex, long- term and short-term relationships and values like faithfulness and its opposites (and the interactions of self-interest and altruism in each of those interactions). He wrote of these issues in complex tortured sentences in his journals, which were always intended for public consumption though he died before their final publication. Here is an example where the word ‘strange’ and my use of ‘queer’ might be synonymous, as he thinks about his tolerance (and more) of a lover’s constant infidelities:

Oh, my strange lifelong romances, almost marriages long-distance, remote-controlled: almost adulteries, non-sexual – this one, I may say, not quite non-sexual, and not yet … I have never seen anyone happier, […] – to be loved with my bizarre constancy, and not only loved but “understood” and (disinterestedly, that is, in disregard of my selfish interest) not disapproved.[10]

Convoluted sentences in his journals are themselves symptoms of un-scriptable experience, or perhaps un-scriptable recordings of that experience, which is usually held to be ‘private’ and treated with special reserve. I think this is particularly true in Wescott’s novels too, especially The Pilgrim Hawk. Facing the conundrum of the supposed preference of queer men for large penises in the face of facts that these were not gifted to ALL men, Wescott – though sharing the preference – for typically complex reasons approached the question as one in which candour led to yet more complexity; the complexity in fact of a story like A Visit to Priapus.

In his Journals Wescott frequently refers to his belief that he had a small penis and that this belief made him overvalue large ones and to blame his lack of success as a lover of men to this ‘fact’. Wescott’s ‘poor penis’ (his description) was measured for the Kinsey study ‘in its two states and both dimensions’.[11] Although Kinsey was to assure him that he had misjudged the matter relative to the norms for penis size collected during the Kinsey Sex Institute research, Wescott still claimed to doctors that this ‘sense of phallic inferiority’ was in fact based on rejection he experienced from male lovers who cited this as a failing of his. In 1949, for instance, citing one such interview he goes on in the Journals to discuss whether it was the more ‘psychoneurotic’ in him ‘to feel dissatisfaction about genitals as small as mine’ or in those lovers who gave it as a reason for rejecting him. Yet, he goes on to say ‘I too felt as my lovers did’.

At some times he jokes about this felt inadequacy but, at other times, he despaired that he was driven to find compensation in substituting sexless love for sexual want or admiration and overvaluation of the penis size displayed by other men. One example of his ability to joke about it comes from a 1976 interview with Jerry Rosco (which he says ‘didn’t want published any time soon)’: in this he claims that large penis size is overvalued and based on adolescent myths about the association of size to potency and virility. In glancing over a book called The Hundred Biggest he had concluded that the utility of these members in sexual pleasure and fantasy was more than limited, the book containing, apart from one exception (on the cover) ‘the most dreary looking human beings I ever saw – woebegone faces and sunken chests and some enormous-looking useless thing hanging down sideways’. He joked that this revelation ‘cured’ him of being a ‘size queen’ forever.[12]

Why would a writer turn this kind of speculation – which will inevitably be thought to be socially inappropriate – into experience worthy of public and literary expression? Why have his avatar say of himself: ‘I am not an Adonis; I am the opposite of a Priapus; Maine Priapus simply may not have found me exciting. None of those I have gone to be with just lately have’.[13] Well, first of all the myth of Priapus has long been a means of validating male role in fertility and undervaluing the female one, which otherwise look obviously primary. In a fresco in Roman Pompeii, Priapus’ member points to the symbol of fruitfulness and oozes superiority and sexual entitlement. It validates selfish male pleasure as something socially valuable (worth more than gold) and desirable to the appetite as well as fruitful.

There is I think a purpose to the use of the classical associations since The Priapus of the title is throughout seen as a curiosity about and an aspiration for an experience that cannot and will not be delivered and is based on a false premise – that there is so a thing as an ideally satisfying experience to be had from the purely ‘masculine man’. Indeed that ideal is just a very thin fiction, the ridden penis no more than a fanciful object no more real than a witch’s broomstick and with perhaps the same purpose – to simulate a flight that never really happens Early on in the story the narrator seems to name one of Wescott’s real partners using only first names, George [Platt Lynes] in reality (who was once the chief sexual object of Wescott’s other live-in lover Munroe Wheeler) and his short sexual dalliance with Pavlick [Tchelitchew], an art photographer and an artist mainly in oils know in public as Pavel.

In the story we are now considering, the narrator, Alwyn Tower – the name Wescott gave his avatar in many novels including The Pilgrim Hawk –underlines the fallacy (that old phallacy again) underlying male self-esteem as an imagination of a symbolically huge penis, a narcissism of imagination locked in the symbols of a body part:

With a mind excessive in everything, overwrought and over-optimistic, … if he really did all that he himself would like to do, in fact he would lack strength and tranquillity for his art. … he is likely to get on the subject of sex, his hobby-horse, always with emphasis upon the actual or imagined magnitude of whatever private part comes into question: his very brain, in an extravagant correspondence to its theme, tumescent, erectible. Around and around and around he talks and, you might say, all up in the air, like a witch astride a broomstick.[14]

What Tower discovers is that his tumescent curiosity over Priapus’ famed private part hides a man who lacks substance and is therefore more likely to be that thing of the watery imagination, Proteus, although not in the guise of adaptability to the current need but a ‘combination of exorbitance and inadequacy’.[15] This man though is neither of the mythological personae he and other people see him as, but merely and simply ‘Jaris Hawthorn’, who used the reputation afforded by his organ’s size as ‘a means to an end, a pretext, an allurement; and as a substitute for what it symbolized, which was what he partially lacked’.[16] And I think it is here we see the wisdom of this book as an exemplum of queer literature, it suggests that queer sex is starved of appropriate scripts for understanding one’s own or another’s sexual and amative satisfaction unless these are acquired merely by luck and reflection on otherwise poorly described experience. He breaks taboos by showing that the penis may not be beautiful and knowing why we must think as men it is: ‘No matter what infantile prejudice you might be swayed by, or pagan superstition, or pornographic habit of mind, you could not call it beautiful; it was just a desperate thickness, a useless length of vague awkward muscle’.[17]

Infantile prejudice, pagan superstition and pornographic habits of mind are poor substitutes for the sexual happiness men might pursue and must convince themselves they are capable of both giving and receiving by the myth of phallic virtuosity. Substitution of phallic myth for the pursuit of mutually engaged love based on imagination open to both self and other is like bad art, which Jaris also makes, be it noted, wherein the amount of committed creative ‘intelligence has never quite sufficed to put in order and clarify even for himself the incessant ejaculation of these pseudo-ideas’.[18] This is strong stuff that is yearning to open up the world of male creativity in love and art to more than exercises of mere virility; one that has developed mutual scripts and schemas for mutual satisfaction of loving and sexual needs. This is what Tower discovers and makes from it an analysis of the effect of the impoverishment of the public realm of genuine understanding of the relationship of thought, feelings and body in the realm of queer love, since it must not be discourse upon or that this be done so in negative not positive ways that bow to inappropriate norms. This is how Tower / Wescott actually says it:

… a certain uncomfortableness of spirit, obscurity of point of view, is likely to keep one from falling in love, and virtually discourage even the lesser or lower forms of desirous imagining: the spirit is prevented from going to work with any ardour to solve the problems of the body. In the case of male in love with male, this is serious, because homosexuality is somewhat a psychic anomaly, not exactly equipped with mechanism of flesh. At least at the start of such a relationship one must fumble and feel one’s way amid a dozen improvised, approximate, substitutive practices. … the worry of what to do and what not to do, and why not and what next and what else; and the dread of the other’s modesty or immodesty or other inexpressible sentiment; and the chill of sense of responsibility, the grievous anxiety of perhaps failing to do for the other what he needs to have done, even amid the fever and rejoicing of one’s own success, at the last minute. …[19]

The long baroque sentence I quote above mimes the absence of models for satisfaction – even the rhythm has a dying disappointment in its fall as it describes orgasm (at such distance and with abstractions not sensual or sensuous language) – because it registers how a failure to tie somatic experience with adequate schemas for the emotions and thoughts makes us inevitably fail each other as lovers. And this is an effect, although of course Tower does not explicitly say this, of the boxing of queer sex into a place where it can never be acknowledged openly, practised by processes of trial and error, and exercised reflexively. No other queer work I know says this SO openly. And yet this work is not rated except by people with an investment (and they are few) in Glenway Wescott.

All the best

Steve

[1] The link leads to a paper that can be downloaded for free with full explanation of these terms with cognitive psychology. Briefly they are mental constructs that guide thinking and behaviour and which are stored for purposes of performance of actions and recognition of things that are seen as socially appropriate and adequate for shared understandings.

[2] Available in full at: ‘…: He came each night to avoid the eyes of everyone who wanted him … . The gossips said he refused to sleep with people because he had a small penis – the leprosy of homosexuals – …’ . Reflecting on art and penis size in ‘dick lit’ with a focus on Andrew Holleran’s (1979) ‘Dancer from The Dance’ – Steve_Bamlett_blog (home.blog)

[3] Glenway Wescott (2001:17f.) The Pilgrim Hawk: A Love Story New York, New York Review of Books

[4] Ibid: 22

[5] Ibid: 22f.

[6] Ibid; 23

[7] Glenway Wescott (2004:42.) Apartment in Athens New York, New York Review of Books 2

[8] Jerry Rosco (2002: 40-43) Glenway Wescott: Personally Madison, University of Wisconsin Press

[9] cited from an interview with the author on December 8th 1982 in ibid: 132

[10] Glenway Wescott [edited by Robert Phelps with Jerry Rosco] (1990: 230f.) Continual Lessons: The Journals of Glenway Wescott 1937 – 1955 New York, Farrar Straus Giroux.

[11]Written 1949 in Ibid: 266

[12] Glenway Wescott interviewed by Jerry Rosco on December 8th 1976 cited in Rosco op.cit.: 235

[13] Wescott 2013 op .cit.: 68.

[14] ibid.: 77.

[15] Ibid: 72

[16] Ibid: 72

[17] Ibid: 61

[18] Ibid: 63

[19] Ibid: 64f.

16 thoughts on “‘Does size matter?’ And other questions raised by the lack of cognitive scripts in genderqueer queer lives: Why we need to look again at a lost queer American novelist – Glenway Wescott, with a focus on the then unpublished story ‘A Visit to Priapus’ in Wescott, G. ‘A Visit to Priapus and Other Stories’ (2013)”