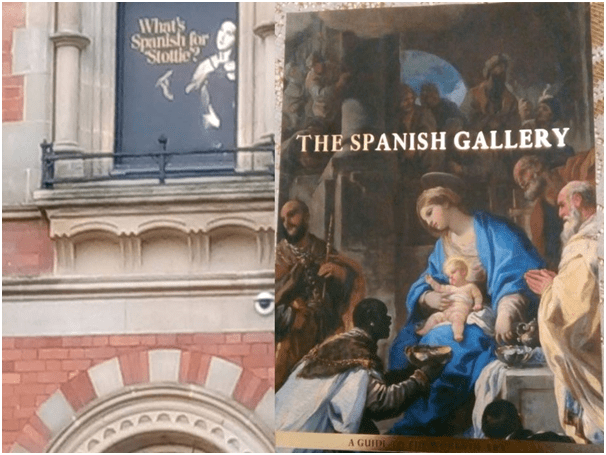

‘What’s Spanish for “Stottie”’? This is a blog about our first visit to the overwhelming riches of, and in, The Spanish Gallery at Bishop Auckland, County Durham. With reference to Jonathan Ruffer (2021) [with Factum Arte and Factum Foundation and Skene Catling de la Peña] The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art, Bishop Auckland, The Auckland Project. This book is also a history of the Gallery’s inception.

It always feels strange to confront the London art and journalistic-cum-academic fraternity at the moment when it is set to confirm all a Northern person’s prejudices about them, especially in the form of the roly-poly arts correspondent of The Guardian, Jonathan Jones.

In his review of the Spanish Gallery lots of rather obvious distaste for the Marbella-loving limitations to taste in Spanish art of the North of England, as they see us in the South I sometimes think, oozes out. Of course, it is semi-disguised as an attack on what is seen as the vanity of one very rich financier and supposed elitist (supposed by Jones at least), Jonathan Ruffer. He avoids saying his feelings are personal by projecting the thoughts imagined to be those of Ruffer himself onto the collection, which we are told is ‘fatally torn between wanting to share great art and preening itself over a cleverness the hoi polloi will never understand’. But maybe Jones’ real metropolitan disdain is not for the ‘snobbery and madness’ which makes this collection of personal preferences of Ruffer’s for High Baroque art of Spain but that very hoi polloi (since hoi is ‘the’ in Greek Jones ‘the’ in the quotation above is otiose) he feels that Ruffer’s ‘vanity project’ is supposedly lording itself over. Meanwhile we intuit how that power is enabled by us poor benighted and taste-free Northerners with our liking for ‘posh wallpaper’ and ‘trite and sentimental texts’ that Jones sees as adorning the collection.

My suspicion that this is indeed so emerged particularly when Jones mocks the taste of the town as more suitably met by a fake tapas bar proposed to open in the Gallery soon than anything like a knowledgeable (and of course London inspired) study of Spanish high art mainly of the sixteenth and seventeenth century Baroque. All of the excesses of religious fanaticism, sentimentality and camp (sometimes) of this period are here belittled by being seen as the equivalent of a taste in the North East for flock wallpaper (not even the case) and brash lighting – which perhaps is the case sometimes.

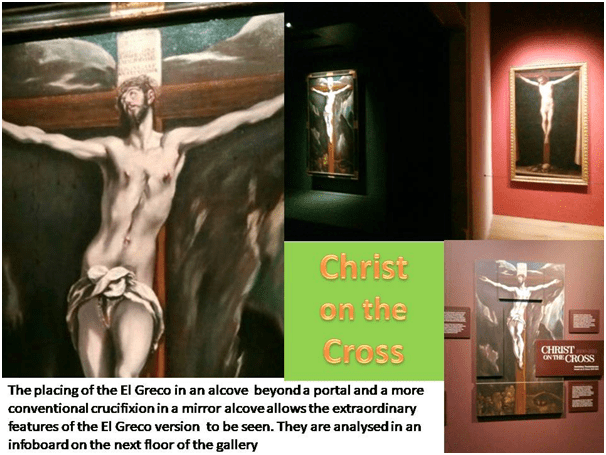

Of course that is not to miss the fact there also some very wonderful and world quality paintings, and not just the rightly loved ones like the Art Fund purchased El Greco’s Christ on the Cross and a most beautiful and lesser know portrait by Velasquez (unfortunately a loan item). Instead Jones takes his Don Quixote lance to pierce the puff of our local windmill by pointing out his (rather theatrical) short-lived joy at the inclusion of a Murillo painting, but – wait! – a fake Murillo.

There is a truly impressive painting high in the central hall: a huge scene of The Miracle of Loaves and Fishes by Murillo. Its deep shadows and time-deepened hues are so authoritative they dwarf the other art, in quality as well as scale. But oh, wait a moment. This is a fake and openly acknowledged as such. It is a hi-tech facsimile by Adam Lowe and his studio Factum Arte, who mix digital scanning with fine craft skills to uncanny effect.[1]

Before I leave Jones to his glow of satisfaction in not living ‘up t’North’, it’s worth noting that he tries too to exonerate the art institutions of international capitals he rates for pandering to Ruffer: in the evidence of ‘plenty of good will towards’ Ruffer’s ‘dream from institutions such as the National Gallery and the New York Hispanic Society, who have loaned works’. I don’t see myself as a great friend to Jonathan Ruffer but that isn’t the point here. Even very rich men contain contradictions: not all of them devote themselves to any dream at all beyond avarice and do not include in that dream an excellent museum dedicated to some fine mining art from Bishop Auckland and Spennymoor itself or to exhibiting the history of a fine ecclesiastical home, power-house and centre of complex cultural networks in the revived Bishop’s Palace (with its wonderful ‘Trevor Gallery’ for temporary shows) and soon-to-open Faith Museum.

In answer to some of the sneers I would also add that the exhibition does go to tremendous pains to contextualise works by their placing in the strangely bifurcating viewpoints created by this old bank’s architecture and by the more regular use of very good information bearing reproductions, which is particularly clear with the EL Greco.

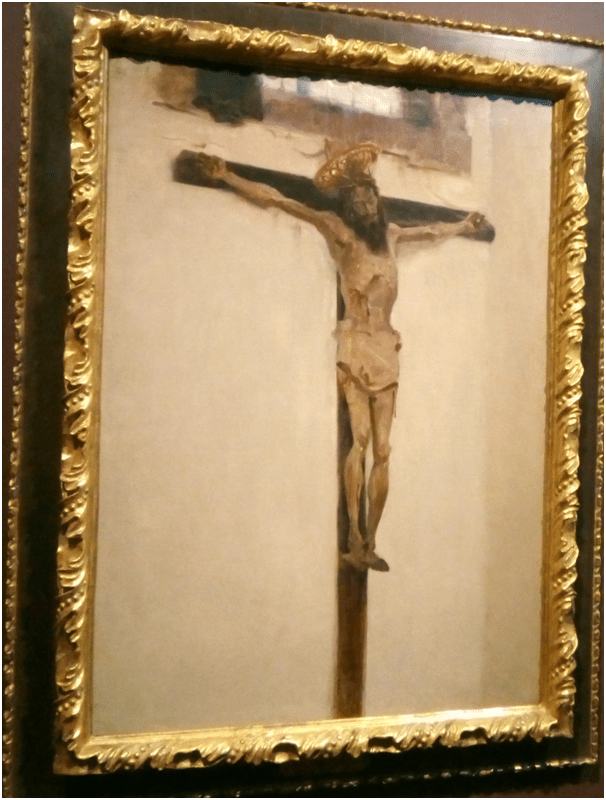

Moreover the contextualisation of paintings does aim to help us see across the perspectives of different historical periods and nations and into themes of social power related to the use of imagery of religious-cum-political significance. The El Greco information board on the third floor (the original painting is on the second) faces a stunning study of a baroque (Velasquez) crucifix painted by John Singer Sargent, a joy in itself, and is returned to the north east.[2] It allows us to see how a twentieth century artist, often classed as either impressionist or realist, interprets an aesthetic as perhaps alien to him as to us.

I can’t find it in me to understand why Jones goes to such lengths to ignore the fact and effect of the borrowings from other galleries, since the contract is an ongoing one and can only yield yet more felicity in its ability to show interesting comparison to the peronal collection. And it is even more startling that Jones plays on the issue of fakes and copies since the gallery itself makes a special feature of the issues raised by the increasing finesse with with which art is now reproduced and even recontextualised, and not only in the fourth floor displays madew to focus precisely on these questions by bringing monumental art, usually unmoveable over long distances anyway into new modes in which to be seen. Indeed the section of the catalogue devoted to this floor makes especial attempts to link the themes of earthly transience and visions of an unrealisable eternity and themes of illusion and materiality so important to the Counter-reformation Church into high relief and contrast.

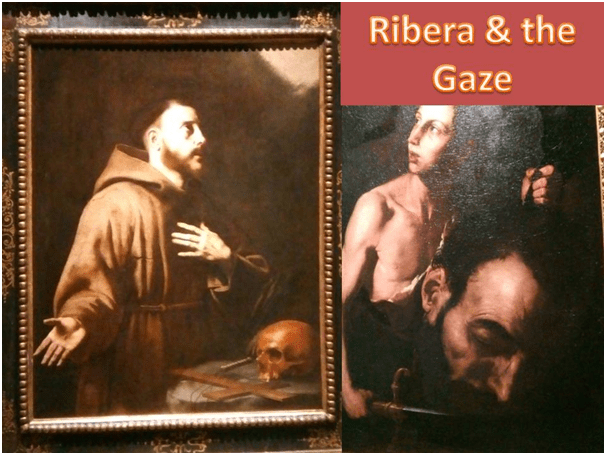

And whilst Josepe di Ribera’s Saint Francis (in the permanent collection) may not be as great a painting as the magnificent John the Baptist, that isn’t, I am so grateful to see how Ribera studies the gaze of those caught out by some greater call to them of which we will never know the content. Both gazing faces, except for the exceptionally dead ones who look dowards – John and the skull on Francis’ desk, look up startled into a light that suffuses their body, and especially their face, with something not of the body, something that glows with some unknowable eternal significance.

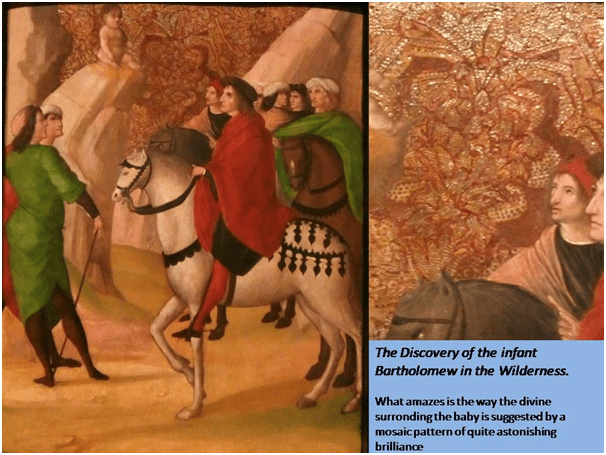

And then these pictures are so delightfully hung that they offer themselves for the inspection of detail in ways that do ‘nothing to stop the heart’, or at least Jones’ heart, it does offer some considerable knowledge of how art sometimes surprises in details, like the replacement of the air by the finesse of a kind of tapestry in the charming picture of the finding of the baby Saint Bartholomew from some fifteenth century master working in the Flemish tradition and certainly influenced by tapestry work. Look at what detail reveals.

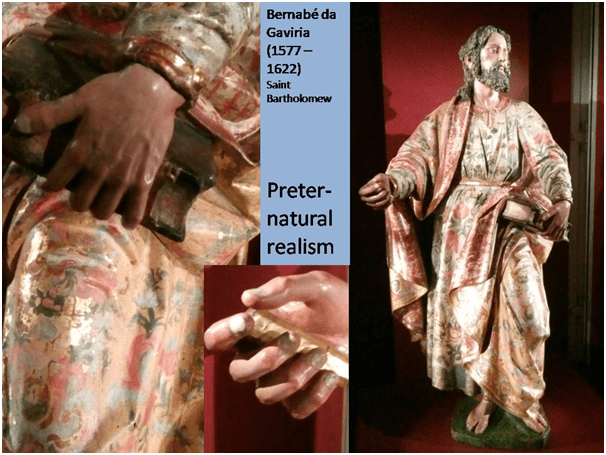

Likewise the immaculate detail of the realistic portrayal of highly coloured statuary of saints rare in other, even other Catholic, countries is placed where it can be seen and examined as in this older Bartholomew, no less associated with copies of woven fabrics of great and colourful beauty as well as flesh that looks like flesh.

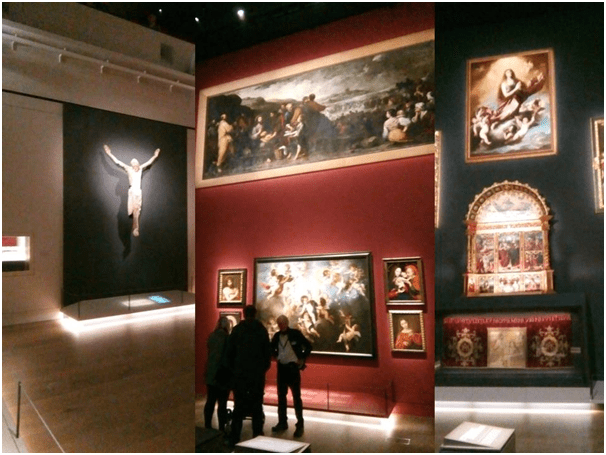

And I think we must reject too the idea that spaces cannot be adapted and adapted brilliantly to show classic art to advantage. The major galleries oiften speak too loudly of the imperialistic traditions of the nineteenth century that often ignores the effects of space – the height and volume both of a room-space which the banking hall disrupts, bringing even hints of the kind of space that you might get in a church. The display of the altar-cloth and crucifix in the Banking Hall feeds off this latter idea without over-emphasising it, as this collage of three views attempts to show.

There is a theatricality here which fits too with the study of the illusory and size perspectives throughout the gallery but especially on level 4. The importance of place may be too obviously marked for some but for me it lends interest to the attempt to create the look of Spanish cities in contempoary panoramic paintings with a (then) impossible view from above. In a corridor showing such panoramas a representation of the river Qual that flows through Seville really helps (me at least) to imagine the city’s mercantile flavour in Baroque Europe.

Finally a plea that people not be put off visiting this gallery by the views of those who think a curmudgeonly attitude to change is synonymous with institutional culture. This gallery is serious about the exploration of ideas about the ownership of original objects and the problems this poses for the accessibility of art and understanding its link to materialism as a changing concept. Level 4 is favoured by Jonathan Jones, who says:

The “fakes” are more moving than the main collection. They take you to Spain. Bring on the chilled sherry and tapas. Actually, the Spanish Gallery will have a tapas bar soon. Meanwhile you’ll have to make do with some very rum displays of somewhat patchy art. It needs a Sancho Panza to keep this place a bit more real.

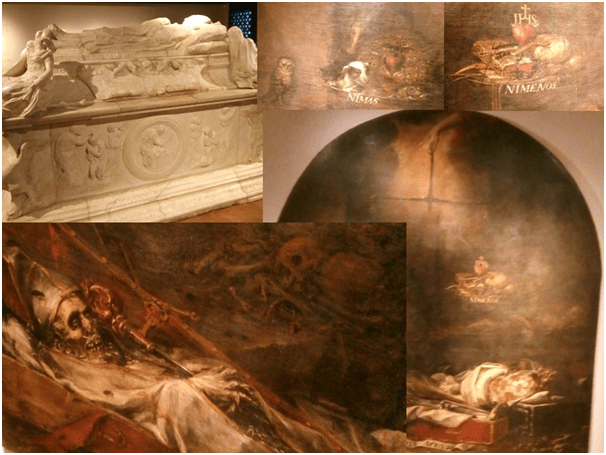

I am not sure that the real means much as a concept in this paragraph. The ability to understand the moveable feast that the ‘real’ appears to be in the diverse eyes of people in whose ideas history and space contribute to cultural history and geography is given to few. That is the case even across classes> cardinal Tavera, whose sepulchre is realised at full size in resin on floor 4, can appear very smug about his eternal value as enshrined in marble. On knowing this object is of resin and produced by 3-D copying techniques we may have freedom to think differently.

In the room we proceed to next are frescoes whose effect is to remind cardinals that memento mori apply to us all. In this fresco wealth, often on the form of huge artistic and ritual objects weighs poorly against ‘good works’, and the counter reformation is as happy to say that to Catholic bishops as Protestants who believe in their state of grace irrespective of works. Of course it is likely that warnings to Church hierarchy are part of the illusion of equality of souls in Catholicism which helped the Church to keep on enjoying its riches regardless, but we need to understand that illusion, and the belief that the earthly was illusory, needs to be understood and that can’t be done when all art critics value is the ‘originality’ of single priceless works owned by the few.. As the guidebook wisely says (or at least I think it’s wise) the use of exact reproduction (fakes if you prefer) asks us to question ‘how we see today, how we represent what we see, and what matters to us by revealing that what we see is limited to our own perspective’.[3]

See the collection. Do!

All the best Steve

[1] Jonathan Jones (2021) ‘The Spanish Gallery review – would you like a scary fresco with your sherry and tapas?’ in The Guardian (online) (Fri 15 Oct 2021 10.08 BST) Available at: The Spanish Gallery review – would you like a scary fresco with your sherry and tapas? | Art | The Guardian

[2] Ruffer (2021:85)

[3] Ibid; 113 (text by collaborators here not Ruffer himself).

9 thoughts on “‘What’s Spanish for “Stottie”’? This is a blog about our first visit to the overwhelming riches of, and in, The Spanish Gallery at Bishop Auckland, County Durham. With reference to Jonathan Ruffer (2021) ‘The Spanish Gallery: A Guide to the Works of Art’.”