This blog is my preparation to see the retrospective exhibition on the work of Marina Abramović at the Royal Academy (the first held there on a female artist) in London on 22nd November. I prepared by reading the gallery’s catalogue and re-viewing an art video: Andrea Tarsia, Svetlana Racanović, Karen Archey & Devin Zuber (with Peter Sawbridge & Associates) [2023] Marina Abramović London, Royal Academy Publications

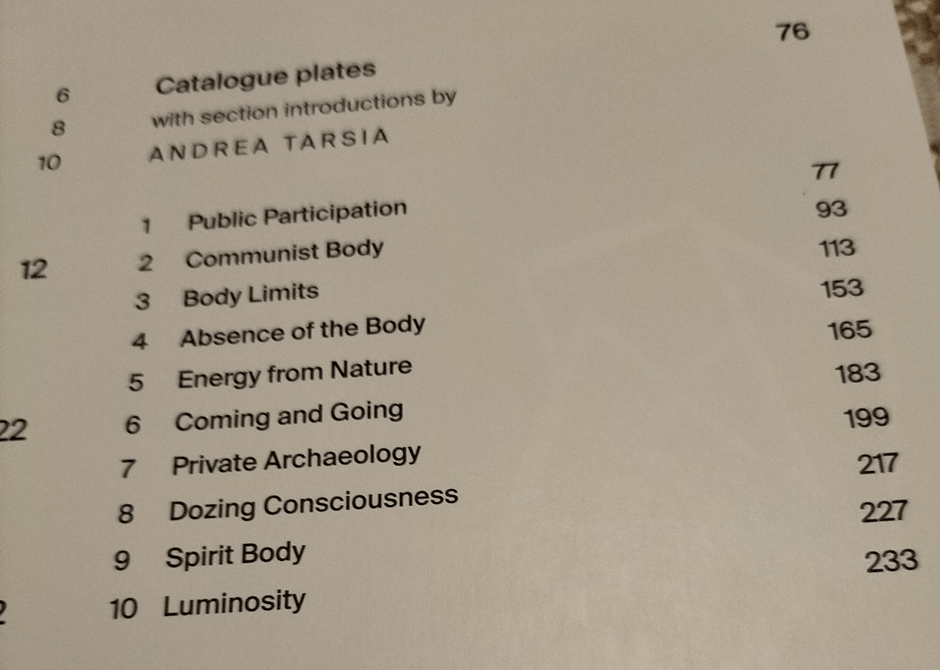

The introductory webpage to this exhibition was the first go-to after I surveyed the catalogue to find little or no basic description of what I and other visitors might see and experience at the long-awaited exhibition. Hence I quote that webpage’s description below. The catalogue, though glorious, does not at any point actually tell you much about the exhibition at least explicitly and my expectations after reading it remained as inchoate as before I did so. I suppose, but cannot be sure,that the sections which organise the catalogue plates into themes might organise the exhibition too into sections. Moreover, the beautiful photographic plates in the catalogue are necessarily from past performances because in performance art the structure art must be contingent to the time, place and resources available for that specific performance. The webpage description then answered basic questions still left open from the catalogue.

Andrea Tarsia describes Abramović’s art by using reference to the great theoretician of ‘Poor’ theatre, Jerzy Grotowski as something that exists, at its most basic, in an embodied and relational form alone in the here and now, unmediated by secondary art-media like film, video or photographs in ‘the actor-spectator relationship of perceptual , direct, “live” communion’.[1] But clearly that is not the whole story or a retrospective exhibition would be impossible. My main question after reading the catalogue then was something like: In this art the actor is the artist herself and she evokes the artist’s own life-story, present appearance and current vulnerability to an audience in some forms that is allowed to approach her as the art’s subject. How then can such an art be represented retrospectively at such distance in time and space from the originating performances to an audience long ago and now absent?

That simple question is answered on the webpage in a paragraph written in the simplest of terms and hence I use this to set my expectations and to describe them to anyone who might read this blog. It says:

This major exhibition presents key moments from Abramović’s career through sculpture, video, installation and performance. Works such as The Artist is Present will be strikingly re-staged through archive footage while others will be reperformed by the next generation of performance artists, trained in the Marina Abramović method.

Live performance art can be both startling and intimate. For Abramović it also has the power to be transformative. Experience this yourself through performances of Imponderabilia, Nude with Skeleton, Luminosity and The House with the Ocean View.

Different works will be reperformed during the run of the exhibition, so no two visits will be the same.

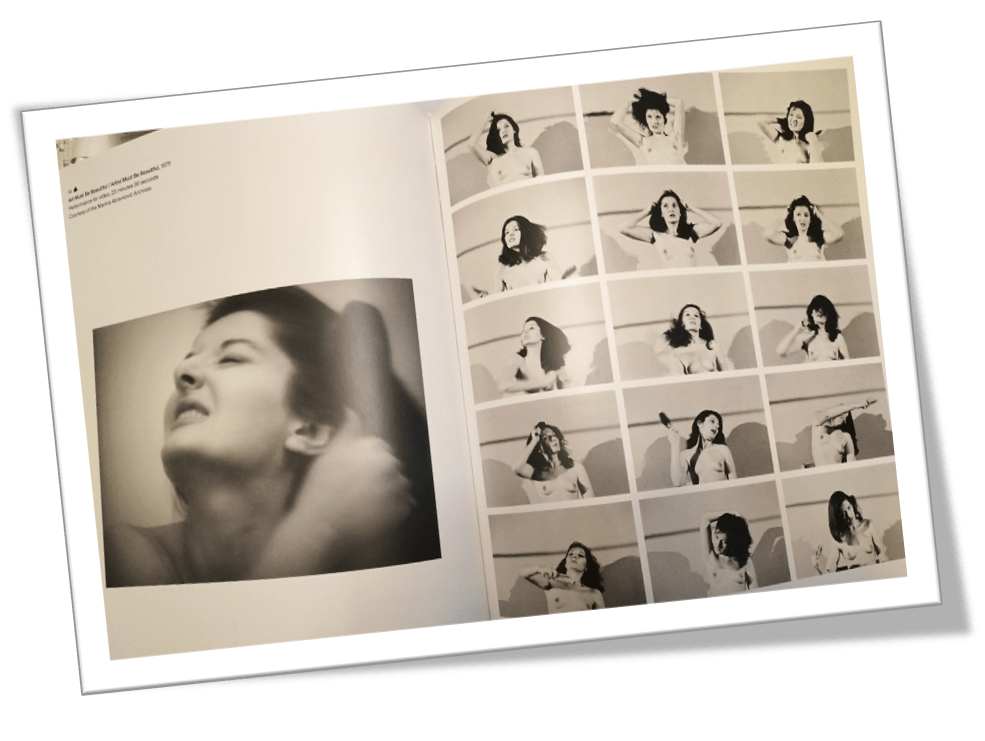

I noted from this, among other things to follow, that secondary representations will be used in the retrospective. Moreover, reading the catalogue’s fuller survey shows that some of those videos are not just recordings for posterity but are considered in themselves to be another and separate work of art from the one that was the originating performance. Moreover, in some of her performance art, such as Balkan Baroque, video recall of past event, of her parents in that work, is central to the present experience. Moreover, some of the original work was designed for video or photographic sequence specifically as in the only one I have seen before (in an exhibition on the self-portrait at The National Gallery of Scotland many years ago): Art Must Be Beautiful / Artist Must Be Beautiful (1975). The collage below shows stills used to represent the work in the catalogue. It represents beauty maintenance as an arduous and self-punishing, even self-violating task.

There is also a link on the exhibition webpage to how both the performance elements and the actor-artists involved are practically scheduled in this exhibition so clarly expectations of a sort can be had. Here is that schedule:

There is, of course, so much more to say about the works I will see, but I prefer to hold back except in one respect, which is about the work in which Abramović fully utilised the vulnerability of the human body using her own body as artistic medium. This occurred in body art where the misinterpretation (especially sexually predatory misinterpretation of her by male observers in particular) could be enacted as in Rhythm O (described a little later in the paragraph below). It is even more viscerally displayed in art wherein she re-enacts violence from the social history she observed and experience – such as the cutting into her own flesh a Communist star as a reflection of feelings about the past Yugoslavia and her high-ranking Communist parents. Perhaps most of all one wonders how the absence of these as physically visceral art will have effect on the retrospective or how they might be substituted to tell her story as an artist.

Performance schedule

Imponderabilia

Daily, approx. 1 hour per performance.

4–6 performances each day.Nude with Skeleton

Daily, approx. 2 hours per performance.

2–3 performances each day.Luminosity

23 September–4 October, 16 October–19 November, 3–5 December, 19 December–1 January

approx. 30 minutes per performance.

3–4 performances each day.The House with the Ocean View

5–16 October (performed by Elke Luyten), 21 November–2 December (performed by Kira O‘Reilly), 6–17 December (performed by Amanda Coogan)

Performed continuously over 12 days, 24 hours per day.

The question remains of how the catalogue section headings (shown in the photograph below) will represent the sequencing or room placement choices (usually with this artist these selections are very much her own choice and based on aesthetic criteria primarily). I wondered, but will find out, whether they are intended merely to suggest themes within the art in the catalogue. If so, they are themes I sometimes find useful. That some seem less useful in framing my expectations may be because they don’t represent or fit my temperament, at least in the abstracted written form with merely two-dimensional photographs to illustrate very viscerally manifested art. I ought to say by the way that the catalogue provides an Augmented Reality feature for smart phones by AN ART APP but since trying it lead to disaster for me on my mobile, I had better not comment. My limited subjective interests moreover do not as a rule extend to the names of things like Spirit Body or even Luminosity. Nevertheless, illumination of my dark corners on these topics is something I will watch out for on my visit on November 22nd.

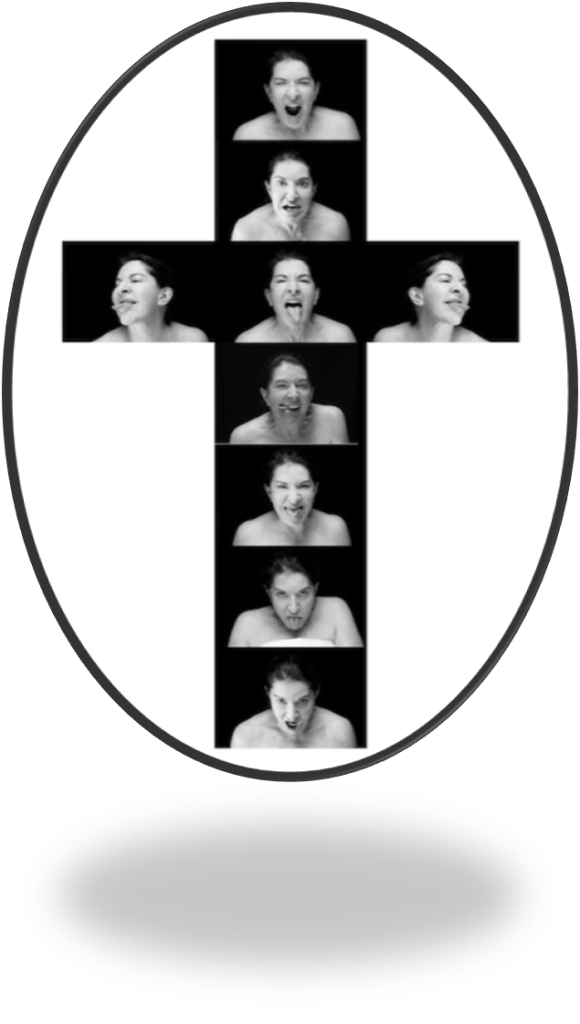

Some of the items have a nature mediate between an original improvisation piece with all the fuzzy definition that implies and a static art form with determined boundaries. The best example of this is the piece Four Crosses of which I give one example from the four below: Evil (positive). The ‘positive’ in the title is a kind of ironic play in itself as I will suggest. In material terms though the four pieces consist of 5-metre-high crosses of aluminium, iron and oak containing stills (actually LED panels and so having the impact of projected light) of the artist’s enacted facial-gestural performances of the ideas Good and Evil (Evil in the illustrated case below). Two of the four crosses contain the same image stills (for Good and Evil respectively)as the positive ones but in photographic ‘negatives’. There is much play though between theme and form in setting the relative meanings of the terms positive and negative here. That may be because in some theologies (especially those influenced by Plato in the West) evil is the ‘negation’ of good (it is for Saint Augustine for instance) rather than being a positive identity as in the hybrid Eastern Christian ‘heresy’ Manichaeism (to which Augustine describes his youthful adherence in his Confessions).

It will be obvious from all this that there is nothing conventional about these art-works, for they are in themselves a commentary on the nature of representation and artifice in art. Devin Zuber says that such work owes something to the artist’s collaborations with Factum Arte, about which group I have touched in relation to their conservation work in the Bishop Auckland Spanish Gallery (see blog at this link). Zuber writes movingly in a way that makes me excited to test my own response to this artwork:

… Abramović’s body has imprinted itself as a sort of geological force, carved by light and lasers into more durable materials, yet in ways that perceptually play with the dynamism and movement of her original performing body. This life (and light) in the stillness of hard materials and rock forms a kind of materialised afterlife, etching a physical space beyond Abramović’s own mortality, and the question of what will happen to her performances once she dies.[3]

Of course this is not just a question of mortality but how one deals with the absence of the artist in the presence of the work (the irony underlying the title of the work The Artist is Present). Presence and absence, like positive and negative of course, are binaries that gain meaning only within each other’s fictional existence – for presence is in most cultures never purely understood as physical presence, just as the physical is never the opposite of the metaphysical or spiritual. In Zuber’s reading light and dark, movement and stasis, solid and numinous play the same games for none of the positive forms here (for in Western culture light, movement and solid are seen as ‘positive’, their binary as ‘negative’, in a way they are not in Ancient non-binary Eastern and Southern global cultures). Hence the two-dimensional representation of one instance from the Four Crosses below can barely convey what I should expect to see and which I hope I will be able to blog about – although I won’t be able to photograph them in situ for that is forbidden in this exhibition the website tells me.

Marina Abramović ‘Four Crosses: The Evil (positive)’, 2019 Corian, aluminium, iron, oak with LED panels. 550 x 357 x 29 cm. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives. © Marina Abramović

Zuber is again brilliant about how movement is inserted, imaginatively or even as a consequence of the saccades of the eye in perception, in this work and I can only describe this for myself after seeing the work in the flesh. Zuber suggests that the effect of the LED screen images is (referencing here the liminal spaces between different artistic media): ‘cinematic, like a sequence of moving celluloid frames, transcending either upwards – as in The Good – or downwards and out, as in The Evil’(my bold emphasis).[4] I will try when I visit (if I remember) to see if those effects as perceived by Zuber work for me as an observer of this art. According to Zuber, the cross in art has always invoked the cross in Abramović’s youthful experience of her grandmother’s Eastern Christian Orthodox belief, held onto in the old Yugoslavia even under Communism, that the cross ‘represented a moment of pure, materialised presence: a flash of kenosis, an emptying of self, where the viewer could be made one with the representational subject’ (I added a link to the theological concept here).

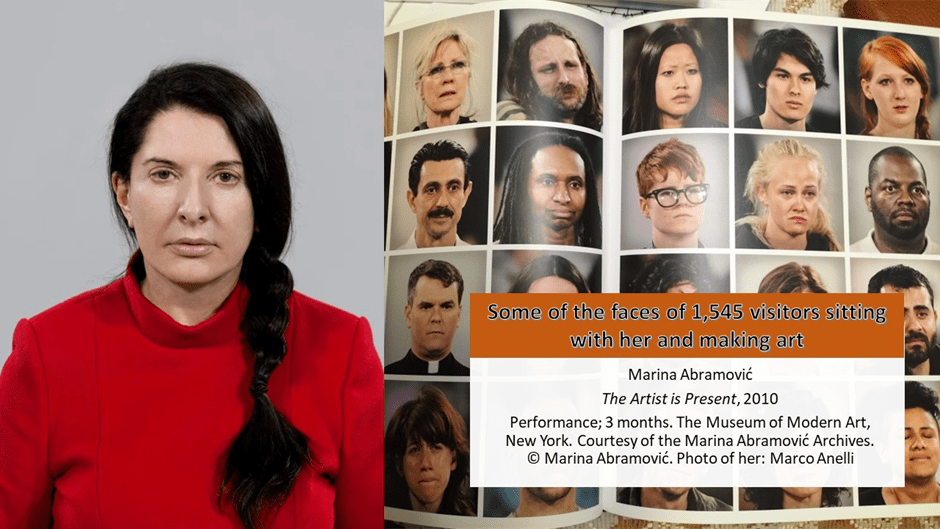

As the webpage text already quoted says, Abramović’s The Artist is Present (2010) is represented by stills (two of which from the catalogue are represented in the collage below) and video of the original gruelling performance (for this work had a duration in live performance of ‘75 days – 716 hours, 30 minutes’). In it visitors were ‘invited to sit in front of the artist in silence for as long as they chose, without any time limit’.[5] The collage as well as showing the deadpan face that Abramović enacted during those sessions also shows some of the varied respondents of the participants, ranging from defensive bemusement to agonised inability to cope with being observed without sign of empathy.

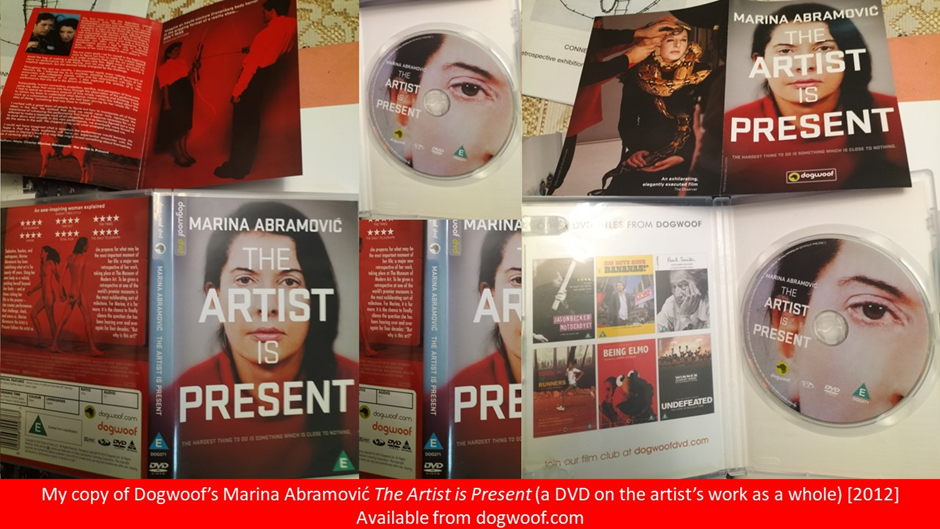

I have seen a video of part of this performance in a DVD I own. However, the curation of video material in an exhibition will add new things, especially given the artist’s involvement in that curation whether she is physically present at the event or not (and officially she is not), not least merely by the presence of a large audience. Much is this artwork depends on the interactive presence of such an audience and I will look out for that – subjective response in exhibitions always is, after all, a register not only of the work presented or represented but also input from the sensation (and cognitive and feeling-based interpretations thereof) of those around you. Think, after all, of the true effect of seeing any live theatre, or sports event. I will attempt to report back on some of those effects of seeing from within a mass of other eyes.

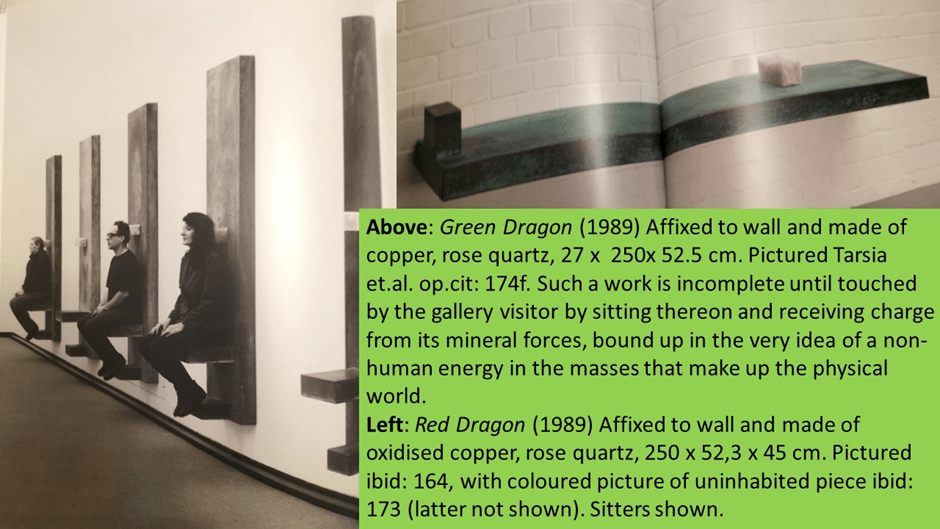

Some of the ‘static’ art items will I suppose before visiting have less chance of disturbing how they are seen relative to items seen in conventional exhibitions. But even here we need to proceed with care for the ‘transitory objects’ (as Abramović called them, with perhaps some relationship to the concept of ‘transitional objects’ in Winnicott’s thought on child development) are very often conceived of in a special way. Devin Zuber in another essay to that referenced above argues she saw these object as channels of non-human energy into human experience, especially those of the gallery visitor. Zuber describes it thus, making it clear that the artist is NOT ascribing magic (although the ideas link with knowledge of shamanism) to the works but believes them ‘to function as daily, ordinary devices, ‘power stations’ to recharge the drained soul, ideally installed in ways that will (re)ritualise everyday life’.[6] To visualise how the object becomes a source of energy the visitor must touch and use it, as Red Dragon and Green Dragon (both from 1989) are used (see the collage below).

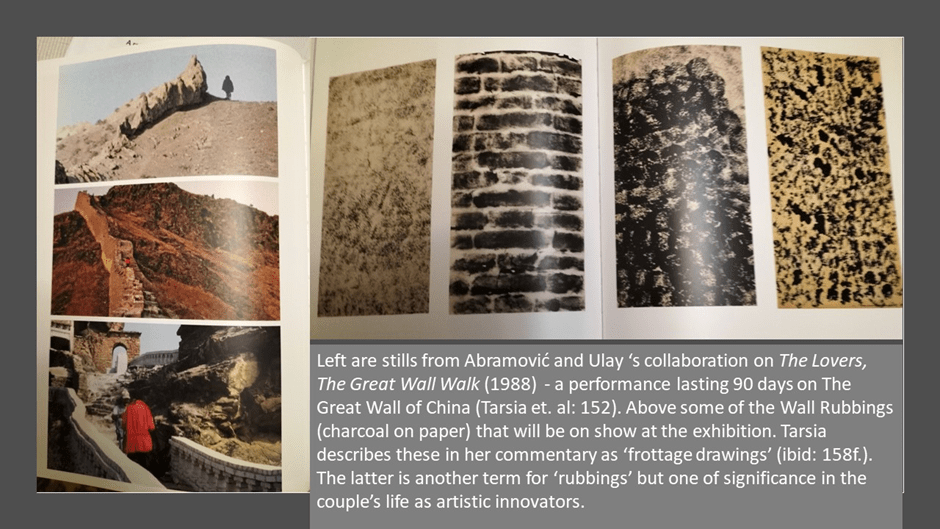

The invited relationship between transitory object and visitor is not always so obvious as inviting an iconic (if rather Bauhaus) use of it. Consider, for instance, the following objects (ignoring in the photograph the break between the sculpted vases since it is merely the page break between the two pages of this photograph of a double-page catalogue illustration). The standing pots/vases (each 180 x 119 cm) are called The Sun and Moon. Tarsia’s commentary says they emphasise ‘distance and absence’ being ‘two black vases in the space where the artist’s bodies had once been, …: one polished and reflective, the other matt and absorptive’. So even here movement (or rest from movement which is also an inhibitory movement) is implicit but I need to find out how that might register on me when I see and hopefully relate to the work for myself. It is particularly so for the work from which the pots derive is usually described as about the material split between the two artists, long collaborators and partners in every sense. Abramović and Ulay, who, after collaborating on The Lovers, The Great Wall Walk (1988) where each started from the opposite ends of the Great Wall of China and met midway, then separated as partners, not even speaking to each other for some time.[7]

The Lovers was an enacted life-event from the beginning, but though planned as a celebration of their marriage, it was eventually conducted, as, in Tarsia’s words, as a ‘ritualised separation’. The vases clearly have differences from each other that may be seen as cognate with those between the couple but I hope for something more nuanced than seeing one partner merely as moon, the other Sun. But let’s see. Other ‘static’ forms were birthed in this walk, including the wall rubbings done by Abramović of parts of the wall (examples are seen in the collage below, which shows a sample of these together with colour stills of, I think, them both on the walk itself).

The artistic rationale of the rubbings was to ‘capture’ the Great Wall’s ‘varying state, from intact and preserved to areas where it had been subsumed into the surrounding rocky landscape’. What Tarsia goes on to say is that the issue here is the relationship between the relative duration and durability of human labour and the dynamism to change in the earth itself, an idea related to the Great Wall’s supposed relationship to the ‘earth’s energy lines’.[8]

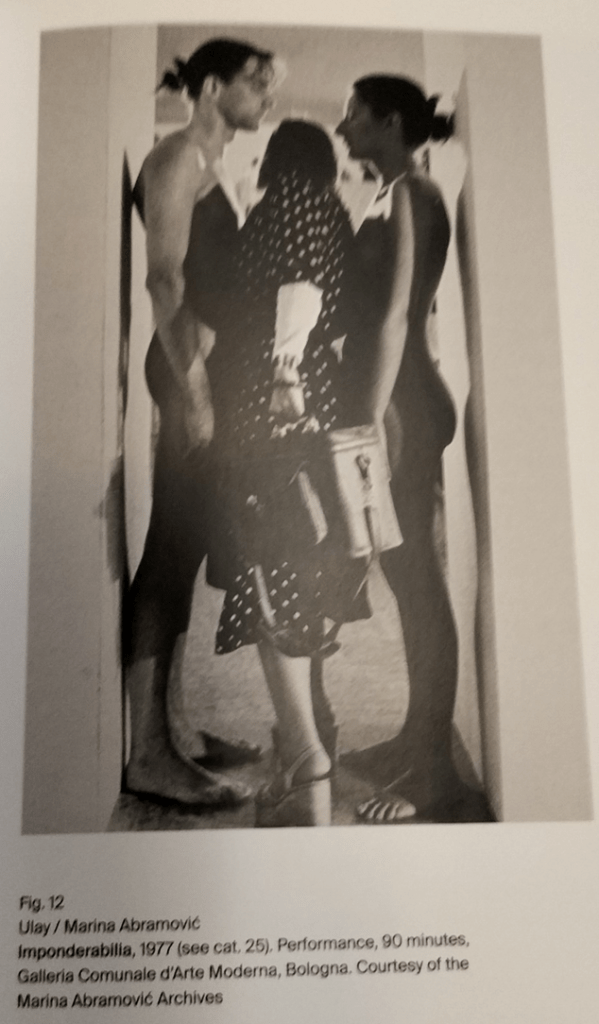

But it may be that the interest in ‘frottage’ has another buried history in relation to the artistic partnership and sexual relationship between Ulay and Abramović, for their earliest work – together with that included in this exhibition, the 1977 work Imponderabilia. In this work conscious or unconscious somatic pleasure, or resistance thereto, from frottage is always implied, for the work has a specialist sense in both the vocabulary of artistic techniques as well as being a word for non-penetrative sexual activity. In Imponderabilia two people, necessarily for the work’s conceptual work a male and a female, stand naked at the door jamb of a relatively narrow portal. This work is to be PERFORMED for 1 hour 5-6 times a day at the exhibition I attend and the male and female are actor-artists, as in the examples in the collage below wherein my first remarks on it may be intuited from the dynamics pictured:

Marina Abramović Imponderabilia, 1977/2023 Live performance (viewer’s right) by Rowena Gander and Kieram Corrin Mitchell, 60 minutes. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives. © Marina Abramović. Photo © Royal Academy of Arts, London / David Parry

What is crystal clear from the illustrations above is that visitors to the exhibit must, with or without intention, allow their body to rub against that of one or both actor-artists. The participant exercises choices (consciously or unconsciously) in doing so – choices in relation to the placement of eyes and body parts, for instance. He or she must choose, since you cannot pass through the portal frontally because of the size of the space, to face the man or the woman. This is a choice which will be heavily determined by, or at least will bear some relation to, the visitor’s awareness of, their own primary sexual orientation or assessment of the desirability of either actor – artist.

Even if that visitor suppresses that motivation, some part of their choice will be determined by such suppression – for instance if I am primarily gay (I am but that doesn’t count for my point) but wish to appear not to be so or fear being visibly stimulated by the naked man standing there, I would face the woman. All of that may depend, of course, on the relative size of my embarrassment about being seen to desire that woman in being seen to face her. In fact when first played and recorded on flickering black and white video, or so Adrian Heathfield tells us, the majority of people showed a ‘studious refusal to look at the fleshly threshold through which they had just squeezed, punctuated by furtive glances back and down. Indifference seems to be the aspiration’.

Of course such indifference on the part of any visitor is probably as performative as any other response and does not rule out sexualised reactivity. That is because the structural dynamics of this work must confront all of the participants in it, even actor-artists however dulled by habituation, of a ‘symbolism and kinetics’ that ‘are caught in the passage, caress and frisson of the coupling’s interloper or third party, and thus the ceaseless movement of desire’. As we see here again, stasis – of the actor-artists’ bodies and facial gestures – implies motion that is sensed even when it is suppressed, or expressed tacitly, if at all visibly, in embarrassment or in other varied ways, by the visitors to the exhibits. This artwork is of course a comment on its context in the world of art where the high value of the nude (male and female, in art traditions) is well known. In the West, nakedness often get fallaciously aestheticized with prohibition on touch and fear of displaying the desire and pleasure of sexual frottage in the ideology of the ‘nude’ as ideal and de-sexualised beauty, as so eloquently expressed by Kenneth Clark. However, there is another issue here that is tied to the autobiographical nature of the artwork for its original actor-artists were Ulay and Abramović respectively (as seen in this illustration from the catalogue from Heathfield’s essay).[9]

Their role in Imponderabilia is even more a vital issue when we considered the hypotheses about sex/gender that both of the couple held and would work with within their collaborations. Even before those collaborations, as Karen Archey tells us, Ulay’s favoured performance piece was a persona Ulay called ‘S/he’, and which Abramović described in this way: ‘half of the face he had completely perfect make-up. Red lips, wavy hair. And the right side, unshaven bear and [a] really rugged look. So it was like a man and woman at the same time’. This persona Ulay himself knew that he carried into their personal and working relationship and both partners felt they represented a combined being that they thought of as the coming together of polarities, in Abramović’s terms at that time (well before the massive development of trans and non-binary thinking in our time), of male and female ‘energy’. [10] Ulay was even more forthcoming, writing (as cited by Archey):

The idea was unification between male and female, symbolically becoming a hermaphrodite. This became increasingly important as our relationship grew more symbiotic. We were living and working in total unity. We used to feel as if we were three: one man and one woman together generating something we called the third. Our work was the third.[11]

If we think again then about Imponderabilia we see ‘the third’ as being the visitor squeezing between but variously connecting the pair that originally was Ulay and Abramović. As Adrian Heathfield tells us the gallery visitor is midway between the polarities of naked man and woman and charged with the energy of ambivalent desires. Thus, the choices faced such as whether to cross through or not, to side against male and female, and to confront the desire to look or not to look, to touch and not to touch must mean they ‘momentarily lose their voyeuristic powers in order to become a work’. What Heathfield does not say is that the three human units of this work are brought together in a relationship of (sexual?) frottage. Hence we might look back at the frottage art of the rubbings of the Great Wall which talk about the pair disuniting in a new way, if one difficult to read simply.

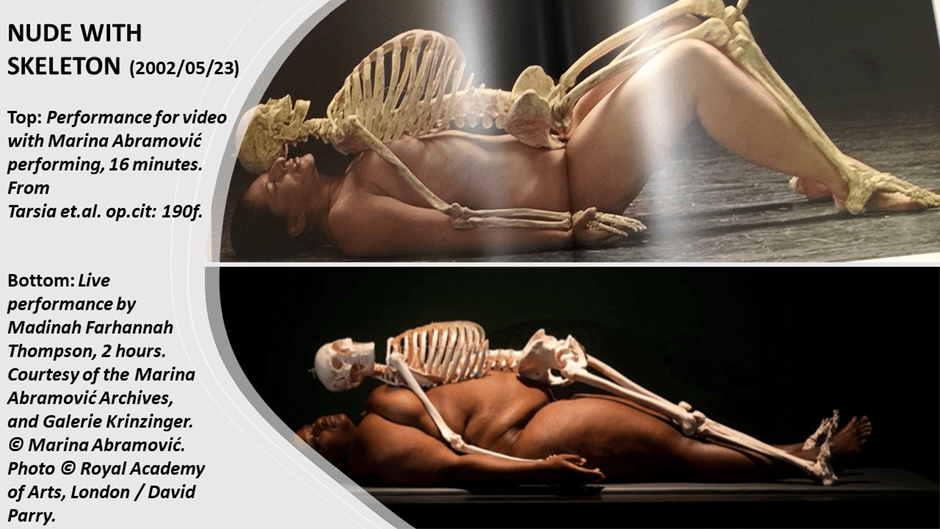

As we have seen already, the use of actor-artists other than Abramović does change the dynamic of reference, meaning, feeling and sensation in works. Look, for instance, of this example (below) of the performance Nude with Skeleton (originally performed before this exhibition in 2002/2005). For Abramović, this work was inspired, Tarsia says, by the artist’s thought about the practice of Tibetan monks of sleeping alongside dead people in order to overcome fears of mortality. The late preoccupation might be thought to be primarily autobiographical relating to personal fear of death but, as Tarsia says, it like other art which investigates what she calls ‘Coming and Going’, or the ‘slippage between, or a coexistence of, presence and absence’.[12]

As difficult as that explanation might feel, it is self-evident when we compare the collaged illustrations above wherein qualities of body and life association (some entirely mythical and stereotypical no doubt) inevitably change the the meanings of the artwork along different dimensions and by the recombination of different domains of reference, such as skin colour and body mass. The issues of presence and absence falls both ways. The presence of another actor is a positive that does not reduce to the negative absence of the original actor, and that is perhaps the thing with the fact of death too.

The performance of The House with the Ocean View (2002) takes many days and I have few expectations of what I shall see, since its history has so been tied to Abramović’s subjective autobiography and observed in her biography and this is also the approach in the accounts in the catalogue. For instance, Heathfield speaks of its relevance to the artist’s known ‘abiding interest in ascetic practices by fasting for a duration, stripping down and ritualising everyday actions’.[13] Zuber also says that she includes items recycled from other artworks and/or performances to draw her ‘self into the event, presumably.[14] But both those readings also suggest, as Tarsia does, that the ultimate object of the work (the set in which she lived for 12 days is pictured below) is a vigil in which a silent audience and an artist, any artist with their own subjective and objective qualities variant to her as, share experience as ‘a coming together resonant with symbolic meaning’.[15] I very much need to report back on this – perhaps if only to reflect properly on it myself.

Marina Abramović, The House with the Ocean View, 2002. Performance; 12 days. Sean Kelly Gallery, New York. Courtesy of the Marina Abramović Archives © Marina Abramović. Photo: Attilio Maranzano.

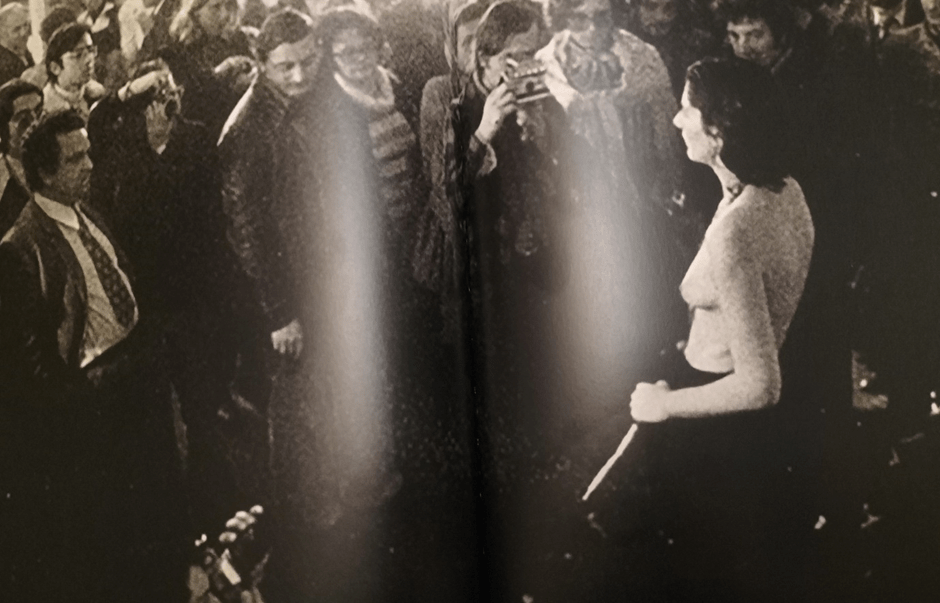

The same might go for the 1997 work Balkan Baroque, in which Abramović sits on a pile of bloody and smelly cow bones cleansing them of meat remnants, partly observed by substitute parents on film. Clearly this work must be represented in the exhibition because Svetlana Racanović has an excellent essay on the work in the catalogue. Even if video is used for these, the visceral reality of self-cutting will be hard to take. And what of the early work Rhythm O (1974) I mentioned earlier? In this Abramović subjected herself to an audience given permission by her to do anything with her body they desired using the objects on a table including a gun and a bullet. Indeed, one man loaded the bullet into the gun and, placing the loaded gun in the artist’s hand, then placed her hand with the gun so it was pointing at her throat. Some men in the audience further undressed her, one poured liquid on her or marked her face and breasts by drawing or affixing sticky items. The suggestion in the piece that it is necessary to understand the resilience of aggressive will as well as the submissiveness in a state we inadequately call passivity seems now a thin justification but I need to see how, if at all, it is represented in the exhibition other than the way it is represented in the catalogue.

The artist facing a crowd: Rhythm O in Tarsia et.al. op.cit: 90f. I wonder if audiences at a gallery could look as threatening as they did with this artist them less well known in 1974.

There is a lot to look forward to and much to ponder about before November 22nd. In many ways I dread as well as look forward to it, for one is bound to learn a lot about oneself – and do I want to know. Oh well ….

With much love

Steve

[1][1] Andrea Tarsi (2023: 14) citing Grotowski in the ‘Introduction’ of Andrea Tarsia, Svetlana Racanović, Karen Archey & Devin Zuber (with Peter Sawbridge & Associates) [2023] Marina Abramović London, Royal Academy Publications, 12 – 21.

[2] Dogwoof’s Marina Abramović The Artist is Present (a DVD on the artist’s work as a whole) [2012] Available from dogwoof.com

[3] Devin Zuber (2023a: 73) in ‘Bridging Between worlds: Visible and Invisible Realty’ within Andrea Tarsia, Svetlana Racanović, Karen Archey & Devin Zuber (with Peter Sawbridge & Associates) [2023] Marina Abramović London, Royal Academy Publications, 67 – 75.

[4] Ibid: 74

[5] Andrea Tarsia, Svetlana Racanović, Karen Archey & Devin Zuber (with Peter Sawbridge & Associates) [2023: 78 – 87 for this description and stills]] Marina Abramović London, Royal Academy Publications.

[6] Devin Zuber (2023b: 60)’Tools for Transcendence: The Transitory Objects’ in ibid: 58 – 65.

[7] Ibid: 153

[8] Ibid: 153

[9] Adrian Heathfield (2023: 37) ‘The Cut and the Line in Time’ in Tarsia et.al. op.cit: 32 – 43.

[10] Karen Archey (2023: 45, 47 respectively) ‘Marina Abramović and Ulay: On Relation’ in ibid: 44 – 51

[11] Ulay cited ibid: 48

[12] Tarsia et. Al: op.cit: 183

[13] Heathfield op.cit: 38

[14] Zuber 2023b. op cit: 65

[15] Tarsia et.al op.cit: 233.