‘It’s not that easy being green.’[1] (Kermit the Frog) This is a blog on why it is not easy to un-obscure the meaning of and story of David Lowery’s The Green Knight. It is incidentally also about how, why and how we saw the film at the Everyman Cinema in Liverpool, on Wednesday 29th September 2021 at 5.15.

For trailer see: https://youtu.be/aRejWo0j7Bs

I am not sure if the eponymous character, who is not really its ‘hero’, would agree with Kermit the Frog about the advantages and disadvantages of the colour that marks his role. He is likely I suppose to be scratching his head (before or after it is either severed or replaced in this film by Sir Gawain) wondering what exactly his name and coloration mean. ‘Do I have a symbolic or representational meaning?’ This we can imagine him saying as he reflects upon himself. It’s not that the Green Knight’s life is hard to be bear, then, that I compare him with Kermit’s song, but that he presents a life style in his very appearance that is not ‘easy to understand’ for either some of characters in the film, or its audience and is therefore decidedly queer, in its supernatural or other non-normative senses. Perhaps both kinds of witness to our green man ought not to feel that meaning can be directly accessed or articulated in some linear fashion though. Indeed this problem is already directly mentioned in the source poem – the place from where the bare bones of at least a large part of the film’s narrative derive.

Ther watz lokyng on lenþe þe lude to beholde,

For vch mon had meruayle quat hit mene myȝt

Þat a haþel and a horse myȝt such a hwe lach,

As growe grene as þe gres and grener hit semed,

Þen grene aumayl on golde glowande bryȝter.

Al studied þat þer stod,

…

And al stouned at his steuen and stonstil seten

In a swoghe sylence þurȝ þe sale riche;

As al were slypped vpon slepe so slaked hor lotez in hyȝe–[2]

Translation in notes if required

David Lowery has not made it easy either for poet-translators of the poem (although neither seem to see themselves in competition) to cohere around his interpretation, even causing controversy by apparently favouring – by making it the film tie-in edition – (or was that the Penguin publisher’s decision) Bernard O’Donoghue’s modern translation of the poem rather than Simon Armitage’s.

Yet Mark Klise, an associate editor at Penguin is cited in a publisher’s online journal as saying about Lowery’s actual attitude to the poem in translation, that ‘everyone’, “… read and reread the poem, and to try reading different translations” (my italics). Though Lowery, like most of us first read the poem in translation at school, his interest is in the way in which translations are often more different versions of a core story:

“He captures how a text as old as this one remains vital and open to reinterpretation. So I’m excited to see how the tie-in does in the marketplace. There’s a lot of buzz out there for this film, and I think we’ve put together the perfect edition to show anyone just how beautiful, captivating, and mysterious a 600-plus-year-old poem can be”.[3]

I think this is well said and rather contradicts what Armitage has to say in a book published in 2021 paradoxically about the lack of cinematic potential in the narrative poem in his lecture to Oxford students as the then Professor of Poetry. He says in that lecture that he thought privately when approached by filmmakers that ‘it would make a really terrible film’. Granted, he was talking about the film in terms of the absence of a ‘narrative arc Hollywood expects us to expect of its products’;[4] and, there is no doubt, that Lowery too feels that to give his film weight he needs to vary the narrative conventions thus referred to, creating some of the obscurities some find in its narrative.

This is a Lowery strength as K. Austen Collins points out in an excellent online review of the film for Rolling Stone as typical of the power with which Lowery revises the content and mode of narrative of oft-told stories and yet somehow gets us back to some of the essence of the original poem. This includes the tensions in it between cyclic (religious festivals and the seasons) and linear views (from starting birth to ending death – in the natural mortal rather than supernatural view of things anyway) of how narrative time unfolds (one of the reasons I believe that Armitage finds it unfilmable by Hollywood). Collins says it is typical of Lowery to ‘offer are at times surprising revisions and riffs on the original story’. In particular amongst those riffs he picks out:

… the setting of the clock — the hard-wired sense of time built into the Green Knight’s challenge — that stands out among the many ideas ricocheting through this story. Time: a notion Lowery has played with before, most blatantly in A Ghost Story, in which the situation of the ghost, its … allows it to shoot forward, into a corporatized future, and back, to America’s primordial stains.

Time is what gives The Green Knight much of its unusual power… [5]

Let’s return to this after I digress on to why this trip was so looked forward to by me as a holiday adventure, because that too is about cyclic returns to this story of the Green Knight over the serial drag of the years of my life. The most coincidental of these was that I was, with my husband, visiting Liverpool with Catherine, the wife of a student of mine from the 1990s (was it then – it was such a long time ago) whom I first met in a seminar I taught on the then Penguin translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight that kicked of the ‘romance’ section of his foundation course in English Literature at a college teaching University of London degrees (then). She loved the film although my own husband rather hated it.

The poem though had also been (this time in the original Northern dialect (and therefore somewhat more accessible to my own native dialect) form of Middle English) visited by me not first at school but in the compulsory Middle English text section of the Year 1 foundation I did at University College London and taught to me by Randolph Quirk. At the time I was unappreciative but now I am nostalgic that I studied literature at a time when it was not thought sufficient not to have visited the major texts in English, from the Old English Dream of the Rood onwards. Those days should not have passed I believe now but maybe that is part of my curmudgeonly old-man attitudinal behaviour.

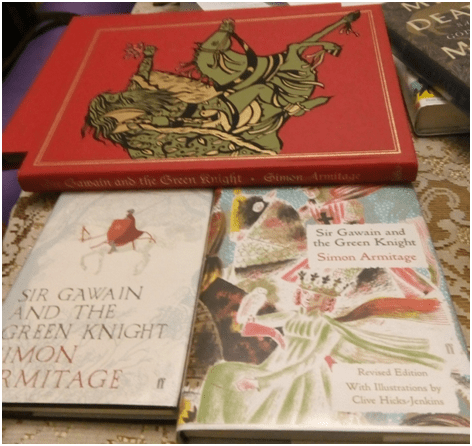

Other examples of its cyclic return include my attention to the publishing career of Simon Armitage – for whom this text marked a change in direction and which he has revised over the tears since the first edition in 2007 and for which purchased (and got signed by him at literary festivals) every ‘first edition thus’.

The poem is full of contradictory value systems, It helps to list some of these contradictory pairs whilst remembering that they interact with each other:

- classical military virtue (traced to Virgil’s retelling of the Trojan Wars at the opening of the poem in which ‘Felix Brutus founds Britain on broad banks’ p.5)[6] against the courtly romantic code of the medieval ‘romance’ tradition;

- Serious warfare and the games of the court[7] – including a kind of crack at the origin of football;

- Platonic against physically achieved sexual love and variants in-between;

- Pagan religions of the natural world conceived as governed by a contradictory plurality of supernatural forces against the cycle of Christian and monotheistic religious festivals, especially those celebrating the birth and sacrifice of Christ;

- Raw nature including predation and butchery against civilised human culture of cookery, costume and hospitality.

- Different forms of male bonding in a patriarchal society set against contracts of different kinds in the contradictory ideals themselves of a heteronormative tradition – both earthly marriage & courtly love for instance.

- …. and much more

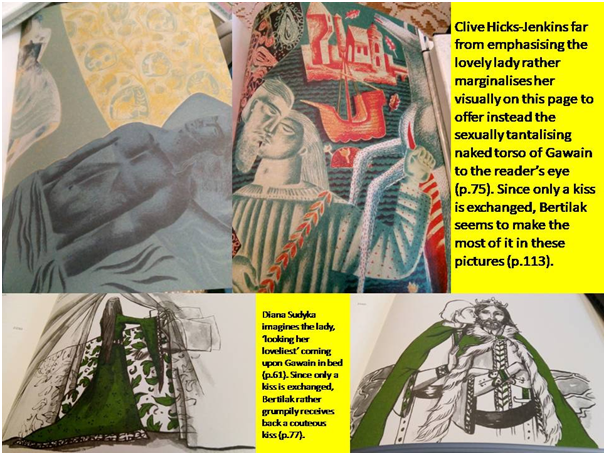

Even as I remember teaching this text, in those days where queer theory was new territory to me as a teacher, I remember learners in this class, including Catherine’s bright husband (then a very young single man), picking up the ‘queer’ way in which the exchange of kisses in Hautdesert, Bertilak’s castle, between the patriarchal lord Bertilak (played by Joel Edgerton in the film) and Gawain is a contract that might, had the lady succeeded in sexually seducing Gawain as instructed, would have meant Gawain offering very embodied sexual love to Bertilak at this point rather than just a kiss. It’s a queer focus in this old poem that is presented very visibly in the film and even in the illustrations of the text as illustrated in some very beautiful editions of the Armitage translation in my collection of Armitage ‘firsts’.

I think I share enough of that story in the text I add to the illustrations below for the story of the ‘exchange’ in the poem to be communicated. The film critic, K. Austen Collins, whom I have already cited makes no bones of the effect of the film’s depiction of these scenes on him, which for all their witty anachronism, make the point, I once tried to make in a seminar at the Roehampton Institute, as was. He refers to, amongst the surprising incidents in the film: ‘the bizarre lust triangle Gawain stumbles into with a pair of lordly swingers’.[8] He may ‘go too far’ but bless him for breaking the spell that says revered and relatively ancient texts are never queer in anyway. Catherine, my husband Geoff, and I now laughed at the ironies of these cycles of revisiting, coincidences revived lost in our joint history coincidental life- occurrences. But the serious point is that once we know a great poem, its many interpretations keep recycling because great old works like that have that power.

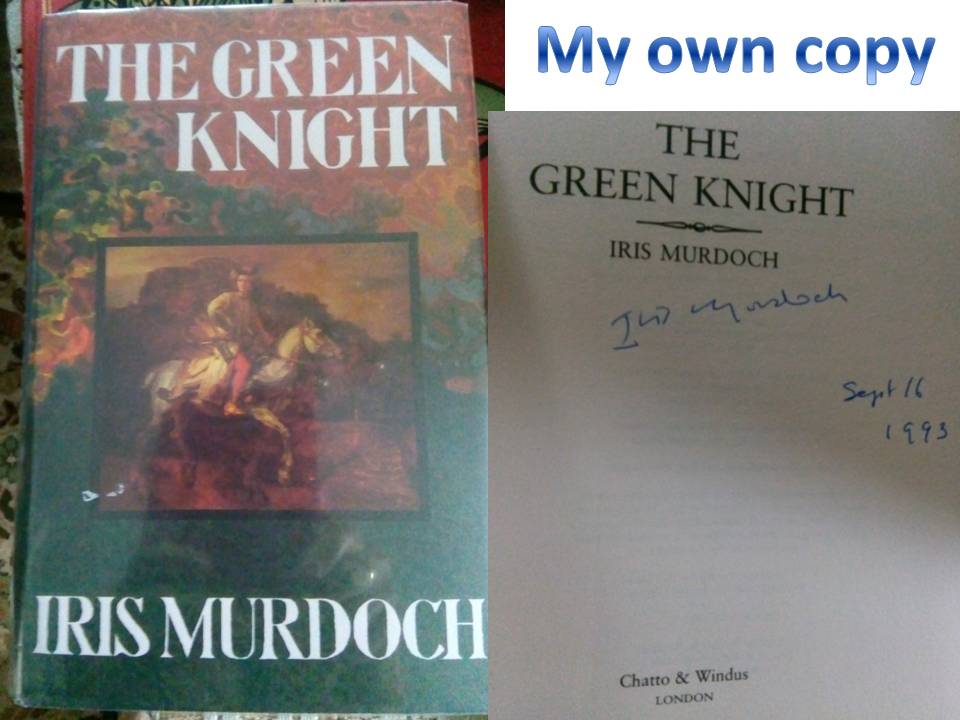

Indeed I think knowing and sharing the Green Knight occurs even intertextually, as the most temporally distant of texts recall each other, just as for me one of my favourite modern novelists when I was at university, Iris Murdoch, did, in her late novel The Green Knight in which the receipt of a deadly blow resounds through a narrative, which like our poem and film, is a story of young men coming into queer sexual and romantic maturity in an ambiguous outdoor adventure, where sex and violence intermix – too complex to analyse as Murdoch’s relationships always were – but nevertheless feeding off complexities in an old poem.

Clement even now fumbled for Lucas’s hand in the dark. … Clement … became suddenly aware that Lucas was about to hit him. … The blow fell – but not on him. Clement saw, as he half fell, half sprang away, the figure beside Lucas of another man, upon whom the savage force of the weapon now descended.[9]

Let’s return to the subtle play of difference between features of both film and the original poem and here I want, for a moment to concentrate on the meaning of greenness, which even the court of King Arthur, as we have seen , puzzle. In some ways this is both clear and far from clear. The exact hue of the knight is described in the lord’s amazement at it as a natural colour (grass-green) but perhaps also that of a worked jewel such as an emerald. In the poem the relation of the Green Knight to the folklore and ritual figure of the Green Man plays through the poem, since he lives in that external nature, but there is also something of other codes here. Green is the colour of natural life and vegetation and life that can take a cut to its embodied form and survive it. Carolyne Larrington reviewing the film for the Times Literary Supplement has quoted a speech by Gawain’s Lady. This Lady is married to Gawain but is played by the same actress as Essel, the prostitute, who had aimed from the first to marry Gawain, despite the fact he is above her ‘station’ in life. They are both played by Alicia Vikander. The prostitute Essel appears to be substituted for in many ways in the narrative by St. Winifred who becomes the Lady I earlier referred to, who is by the end of the story Gawain’s wife. This marriage is at the expense of Essel of course who had wanted this status. These complex links may or may not underlie the speech Larrington quotes which, for the purposes of the film as opposed to the poem, ‘unravels the colours associations’:

… green is the colour of earth, of living things, of life. And of rot … But should it come creeping up the cobbles, we scrub it out, fast as we can … Moss shall cover your tombstone … this verdigris will overtake your swords and your coins and your battlements and, try as you might, all you hold dear will succumb to it …[10]

It’s a very queer thing is green as Manet’s use of it also witnesses. It represents neither death nor life, and is neither totally beneficial nor totally malign. Nevertheless it is the absolute victor over the tawdry effects created by human culture. And though nature must comprise the experience of both life and death, there seems more to it than this convenient binary association of opposites offers. What it seems to challenge most are the systematic ways in which cultures attribute ‘worth’ or ‘value’ or ‘dear’ness. In the end, in a world taken over by green nothing much matters – life, death, military or sexual codes of behaviour, pleasure or pain, love or hate.

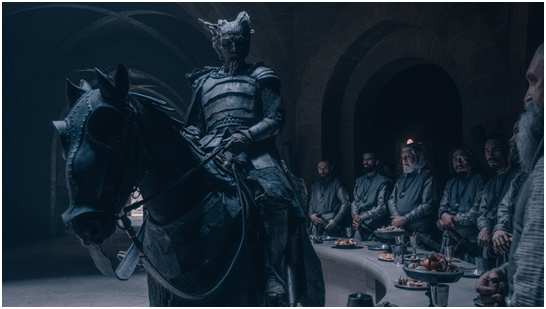

When the Green Knight enters the film he is not only green but oozes green into everything around him: mise en scene and characters. Look for instance at this still:

I think this is what makes the film so obscure – as if it questioned any attempt to make sense of itself. Hence I don’t blame my husband that he found his interest in the film desiccated by the perpetual messing about with temporal frameworks for the narrative in which no decision humans take has value and its deliberate obscuration of even the expectation of comprehension. Larrington is correct to say that ‘thorough comprehension’ is a ‘chimera’ but perhaps fails to note the irony of the director’s decision to embrace the challenge of facing incomprehension in the statement of his she cites:

When you watch the finished film, you will see evidence of my very linear and rather literal journey through a text I did not thoroughly comprehend’.[11]

We need to keep this deliberate obscuration of understanding in mind when we look at the treatment of gender in this film, particularly in the light of Lowery’s very un-literal additions to the Gawain story, including the addition of one other being ‘beheaded’ in a kind of game – that of sexual love. This character is St. Winifred, a saint who was indeed decapitated, and it is Gawain who must find her head and return it to her. His reward is that he marries the character played by Vikander : it is the Lady. We need to confront though a question here. Is the fact that she is played by the same actor indicating St. Winifred is this telling us that she has some association with the ‘low-life’ character, Issel, we see in the brothel at the opening of the film? Why if not does Lowery have the same actress obviously play both parts? Yet again, I’d venture he taunts us about the meaning of sexual and social codes – fidelity to vows for instance or even to more slippery sexualised expectations (Platonised or not) such as ‘courtly love’.

Female social roles such as mothers, as well as wives, are the source of both temptation and salvation in this film but it is NEVER certain which. The meaning of the girdle, which two women promise will save his life from masculine aggression (and it is never clear that they are talking about the SAME girdle, though it might be) is never clear. The girdle is associated both with magic and the supernatural – and at one point seems to metamorphose from a serpent proceeding out of a woman’s body. The girdle saves lives but it also endangers them because even Gawain’s head that appears to remain securely attached after a game with the Green Knight that it might fall off its own accord (as Gawain’s does in one of the two alternative endings his choices offer him in the Green Chapel).

Let’s face it: ‘beheading’ is a highly symbolic action that is not covered entirely by the notion of castration, although it clearly does have that meaning of ‘unmanning’ associated with it and therefore fits into the fluid play with sex/gender in this film. Beheading has exempla in types such as Orpheus and John the Baptist and meanings in religions attached to each. It can connate with a deliberate giving up of cognition as a means to understanding OR of the sexual body or its familial types in psychoanalysis (see link above). In my view, these are the not altogether comprehensible associations the film plays with and sometimes discards, although sometimes not. That it remains ‘obscure’ then is hardly surprising and ought to be expected. People have varying tolerance to being offered something whose comprehensibility is neither straightforward nor unchallengeable at any point, but surely art demands this potential. I think so anyway. In the end the queerest works of art we have are those which deny readers, in a commodifiable form at least, meaning or ‘moral’.

Even the poem cannot have the discomfort of some of its meanings shorn. Simon Armitage, for instance, is keen to see the meaning of this poem as lying less in religious or social functions of our literature and more in less articulate ones which art provides without offering that it can be reducible in any way to other discourses. Yet in his lecture at Oxford he disdains the poems sexist ‘diatribe against women’, equating the sex with the source of temptation, weakness and failure to achieve manhood or any other goal that he claims to seek. This speech he concludes MUST be written by someone other than a poet as subtle as the anonymous Gawain-poet:

What distinguishes the Gawain-poet from more jobbing writers is the virtuosic reshaping of such material (he refers to sources plagiarised by the poet as a right in medieval writing)into a unique stylistic enterprise, whereas what distinguishes Gawain’s misogynistic outburst from the rest of the poem is its cut-and-paste complacency – the feeling that an entire system-built section has been airlifted from one text and parachuted into another. I can offer no evidence for that theory; it’s simply a speculative observation made by a poet looking at a poem and recognising the craft and craftiness of the greater part of its composition, compared with the crude mechanical excursus that takes place four stanzas from the finish line. Or maybe the poet was just having a bad day; …

It is good and right that Armitage gives alternatives but my own feeling is that we should not expect to feel comfortable with everything in a work of art but to expect contradiction therein as the work struggles ideologically within itself to make sense and still satisfy so many kinds of interest existing in its audience and even in an unresolved poet. In that sense, I think David Lowery’s film is in the same tradition and i just love – reducible to no simple code at all. Although if there is one meaning I’d guess it is that life is NOT a game ever but highly consequential, whether we are talking about sex or martial endeavour for women, men or any variation thereof.

All the best

Steve

Here is the offending ‘misogynistic outburst, which I don’t offer translation for, because it is so offensive even if culturally dominant for so long. in its simple identification of women with treachery, using the old Christian and magical types (Eve, Dalila, Bathsheba, Morgan le Fay) comforts all those ‘poor’ men who were ‘biwyled / With wymmen’.

Bot hit is no ferly þaȝ a fole madde,

And þurȝ wyles of wymmen be wonen to sorȝe,

For so watz Adam in erde with one bygyled,

And Salamon with fele sere, and Samson eftsonez–

Dalyda dalt hym hys wyrde–and Dauyth þerafter

Watz blended with Barsabe, þat much bale þoled.

Now þese were wrathed wyth her wyles, hit were a wynne hugePage 67

To luf hom wel, and leue hem not, a leude þat couþe. [folio 123v]

For þes wer forne þe freest, þat folȝed alle þe sele

Exellently of alle þyse oþer, vnder heuenryche

þat mused;

And alle þay were biwyled

With wymmen þat þay vsed.

Þaȝ I be now bigyled,

Me þink me burde be excused.

[1] Simon Armitage (2021: 231) A Vertical Art: Oxford Lectures London, Faber & Faber..

[2] Anonymous (Text edited by J.R.R. Tolkien and E.V. Gordon – pages 7 -8, ll.233 – 245 with my omission) Sir Gawain and the Green Knight Available from the University of Michigan online at: Sir Gawain and the Green Knight (umich.edu) ‘The guests looked on. They gaped and they gawked / and were mute with amazement: what did it mean / that human and horse could develop this hue, / should grow to the grass-green or greener still, / like green enamel emboldened by bright gold? / Some stood and stared.. Yet several of the lords were like statues in their seats, / left speechless and rigid, not risking a response. (Armitage 2007 op.cit: 15).

[3] Mark Klise cited: Publishers See Green in ‘The Green Knight’ (publishersweekly.com)

[4] Simon Armitage (2021; 231) The Vertical Art: Oxford Lectures London, Faber & Faber. I have blogged on this book – see this link.

[5] K. AUSTIN COLLINS (2021) ‘Heroes and Villains: Dev Patel Takes on His Greatest Challenge in ‘The Green Knight’ in Rolling Stone (online), available at: ‘The Green Knight’ Movie Review – Rolling Stone.

[6] And fer ouer þe French flod Felix Brutus / On mony bonkkes ful brode Bretayn he settez wyth wynne, .. (Armitage 2007: 5: …over the sea of France/ on Britain’s broad hill-tops, Felix Brutus made his stand.’)

[7] With mony luflych lorde, ledez of þe best, /Rekenly of þe Rounde Table alle þo rich breþer, With rych reuel oryȝt and rechles merþes. /Þer tournayed tulkes by tymez ful mony, Justed ful jolilé þise gentyle kniȝtes, /Syþen kayred to þe court caroles to make. (Armitage 2007: 7: ‘all the righteous lords of the ranks of the Round Table / quite properly carousing and revelling in pleasure. / Time after time, in tournaments of joust, / they had lunged at each other with levelled lances / then returned to the castle to carry on their carolling.).’

[8] K. Austen Collins op.cit.

[9] Iris Murdoch (1993: 85) The Green Knight London, Chatto & Windus

[10] The Lady cited in Carolyne Larrington (2021: 15) ‘Games and thrones’ in The Times Literary Supplement (Oct. 8th 2021).

[11] David Lowery cited Larrington, op.cit.

3 thoughts on “LIVERPOOL VISIT 5: ‘It’s not that easy being green.’[1] (Kermit the Frog) This is a blog on why it is not easy to un-obscure the meaning of and story of David Lowery’s The Green Knight.”