‘Mother was also a kind of weaver’.[1] This is a blog that asserts the bizarre folly of excluding the biographical and crypto-biographical from the appreciation and understanding of great artists. It reviews the Artist Room: Louise Bourgeois exhibition at Tate Liverpool seen there on Thursday 30th September 2021 with my husband and our dear friend Catherine. Using, in lieu of there being a catalogue a fictional autobiography of Bourgeois by Jean Frémon (translated by Cole Swenson) [2018] Now, Now, Louison London, Les Fugitives.

For much more see: https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351/art-louise-bourgeois

I first encountered Louise Bourgeois’ work in a small exhibition of her work at the Sigmund Freud museum in Maresfield Gardens, London – the museum in Freud’s former home and preserving the implements of his trade and his collection of ancient artefacts which he had analysed in various works (not least Moses and Montheism). Freud is inseparably linked to the world of art and art theory. Yet Bourgois argued that Freud had neither aesthetic sense, given the randomness of the forms in his collection of antiquities, nor insight into art which remained a kind of symptom of unresolved life-trauma.

I simply want to know what Freud and his treatment can do, have tried to do, are expected to do, might do, might fail to do, or were unable to do for the artist here and now. The truth is that Freud did nothing for artists, or for the artist’s problem, the artist’s torment—to be an artist involves some suffering. That’s why artists repeat themselves—because they have no access to a cure.[2]

This is despite the fact that Bourgeois sought a cure herself from psychoanalysis for the acute depressions and suicidal thoughts that arose, she said, from her family experience and particularly witnessing her father’s affair with a governess and her mother’s apparent impassivity to this man’s philandering nature. Christopher Turner in an article in The Guardian from April this year, recounts the history of her involvement succinctly:

In 1951, suffering from depression after her father’s death, she entered therapy with Dr Leonard Cammer. The following year she switched to Dr Henry Lowenfeld, a second-generation Freudian who had emigrated to New York in 1938, the same year she did. Lowenfeld had been trained by the Marxist analyst Otto Fenichel in Berlin, where he was also a part of Wilhelm Reich’s radical group, Sex-Pol.[3]

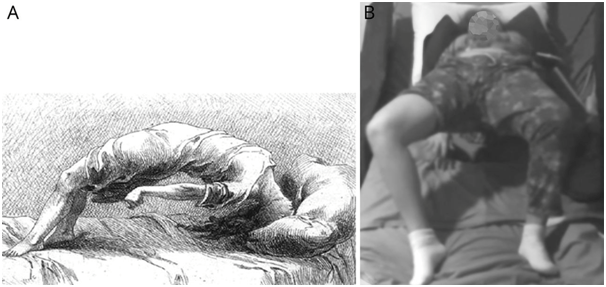

That is an impressive acquaintance with therapy but Bourgeois continued to insist that a cure remained inaccessible, possibly because it would remove from her her one true goal of sublimation of trauma into repetition of basic symbols and icons that were always more than JUST symptoms. In this context, contacting Bourgeois’ art inevitably also meand contacting her life at different levels of understanding or its absence. She diagnosed herself as an hysteric in the classic form analysed by Freud and Breuer in Studies in Hysteria and studied the form of hysteric forms in the plastic bodies of Charcot’s patients at Salpetriere which so fascinated Freud too, including the famed arc of hysteria, whose occassional appearance is now thought by some to be the result of focal epilepsy (see photograph below and reference).

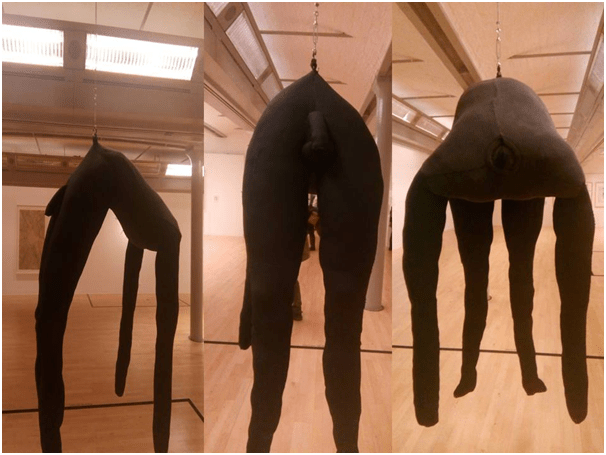

In Charcot artists saw that the body is subject to gestural sculpting by processes beneath conscoiusness and are part of the body’s control system that sometimes follows patterns that are not consciously chosen and Bourgeois was fascinated by these body arcs, although not necessarily only in the form of the symptomatic architecture of involuntary neurological events. Thus at least some of the meanings in Single II, a work in this exhibition:

Powerful feelings are evoked by this work that can’t be resolved easily by understanding the source of its imagery in Charcot. It is clearly an evocation of body in a proximity of dependence, literally and figuratively. It cannot escape its continual dynamic shaping since its form is an effect in part of distribution of forces including gravity in causing that shaping. Hanging as it does it both evokes and avoids being seen as a representation of recognizable parts such as arms and legs, and this is emphasised by the ‘sexing’ of the aspects of the piece with respectively an iconic penis and vagina at top of each pair of hanging limbs.

At times the form is that of an animal or insect, almost from some aspects a partial spider (since it has only 4 ‘legs’). In situ, the viewer is more conscious than a photograph allows of the sewn together textiles from it is formed and given texture, of its softness turned hard only in the vision by its suspded tensile form and only as long as we do not touch the surfaces and feel their texture. Yet we are invited to do the latter just as poewerfully as we are repelled by the fear of disturbing its achieved form, since the latter is so clearly dependent on physical forces that could by touch or hold be manipulated.

This piece inevitably suggests ideas to the viewer about sex/gender, sexuality and the dependence we sometimes have on these forces. In this piece the binary nature of the piece’s sexual parts are kept apart from each other and do not, indeed cannot communicate. Perhaps this is a clue to it’s title Single that contrasts with other pieces where two body forms come into close contact that appears sexual and symbolic of interpenetrative acts but what it also suggests is that there is no single sex/gender but one which continually takes new forms and is dependent on different suggestive forms which resemble the body and its variations that are not purely determined by one continuum of biological sex. For Bourgeois continually queers the acceptance of a single gender iun a binary framework and emphasises multiplicity of combinations and dependences, something she often emphasised by carrying around the huge phallic piece, Fillette (‘Little girl’ in English), with which Mapplethorpe famously pictured her in old age (use link to see the photograph). Of course the name Fillette suggests Freud’s least perceptive notion ‘penis envy’ in the young girl is the source of her desire to birth a baby from er father as its substitute, but in the joking way that allowed Bourgeois to do something much more liberating in her examination of sex/gender than the bare effect of that throw-away idea from Freud.

We can return here then to why Bourgois nevertheless felt a need to teasingly play with Freud’s view of the sexual aetiololgy of neurosis, neurotic symptoms (such as those of ‘hysteria’), and even of art. And it is here that I think we cut off our ability to have a deep relationship with what art offers to us if we cut off access to the ‘life’ and representations of the life of the artist in her own and other’s perspectives. This is why I was fascinated to find a book, of which I was previously unaware, in the Tate Liverpool bookshop a novel by Jean Frémon which takes the form of a fictional fragmentary autobiography in which Bourgeois is the narrator, a novel praised really deeply on its cover by Siri Hurstvedt, that champion of reimagining the role of sex/gender in art. The effect of reading this novel has not only reinforced my own belief in the need for insights into an artist’s biography but of the greater importance of collaborative imaginations and re-imaginings of that life in which the artwork, viewers, the artist and perceptions of the life of more than one person all collaborate. This is both an approach that isn’t the dryasdust postivist examination of evidence for a notion of demythicised and ‘objective’ (that myth again) grasp of the life nor a de-individualised notion of life that is too general to touch upon themes specific to this one artist, such as a dependence entirely on Freudian (or Jungian come to that) symbolism.

Frémon knew Bourgeois personally but this is the fictional autobiography of an artist primarily that starts from development of events into significance, not least the ways in which sex/gender is experienced in events and relationships peculiar to bourgeois such as her relationship to her father and the ways in which this was signified not only in art but life decisions like her refusal to supplant her father’s name by her husbands’s and his transformation of her to the son he had always wanted in naming her ‘Louison’ as a play upon Louise and Louis as gendered names without making that wished for metamorphosis outside of play, so that in photographs boith father and mother laugh at seeing in them; ‘Louison as a geisha, in a large flower print silk kimono with a paper umbrella on your shoulder’. A girl playing a boy playing a sexualised female stereotype is at the heart of fantasies in Single II. Yet is this insight dependent on its accuracy to what the Bourgeois family (here Mme [or Maman] Bourgeois’s tone captured in her glance over family shots in the sentence I quoted) literally said: or in more abstract terms is accuracy to the literal truths of their family life a necessity in exploring artistic personality. Some academics think it is.

Here is, for instance, Michael Hoffman luxuriating in probably the most damning review of the fictional biographical novel for lacking the ‘reliability’ that comes from ‘original research’ of the academic (that is to say Hofdmann’s) kind. It is as if this scholar of German literature did not realise the fictional autobiography of real historical persons without claim to either quality was a genre practicised by the great German Romantics. He targets his scorn at both Colm Tóibín’s recent (2021) novel of that genre about Thomas Mann, The Magician, and his older work (2004) on Henry James, The Master.

Both books to me are like biopics, a slightly vulgar, slightly unattributable, cod replaying of celebrated or distinguished lives. Call them bionovs./

…

In all this soap opera, tedious and poorly told and lacking insight and accuracy to them as know, breathless and arbitrary and inconsequential to others, it is hard to see “Thomas”, …

Michael Hofmann (2021) ‘Mann without qualities’ (that old literary joke) in The Times Literary Supplement (September 10th 2021 – some weeks before the novel was published in UK. Ggrrr!), page 18.

What isn’t difficult to see here is the emboldened class prejudice registered in the wittily ‘undereducated’ cod phrasing of the reference to original researchers and scholars as ‘them as know’ (like a speech from one of Bernard Shaw’s underclass in Pygmalion), the reference to popular genres (biopics and soap operas) and the distaste for vulgarity and for those to whom, they not being identifiable at all since they are not one of ‘them as know’, truth and accuracy are ‘inconsequential’.

It stinks of the academe of the early twentieth century – grossly wallowing in the entitlement of the ‘few’ to insight, truth-telling and sensitivity denied the ‘many’. Now this may be an attack just on Tóibín as a particularly poor writer in Hofmann’s view that does not apply to others, after all he excepts Penelope Fitzgerald and his own father, Gert Hofmann (who died in 1993).[4] But it is difficult to sustain such exceptions from the specific objections that novelists need to invent things that feel different from a biographer’s truth (where the life says hic’ surely even Goethe romancing and pillaging for his own purposes the life of Torquato Tasso is ‘allowed to say hoc’). It feels so pertinent to me that Hofmann illustrates his point about the necessity of a degree of historical accuracy with reference to the grammar of Latin syntax (thus again defending truth from the many with ’small Latin and less Greek’).

It is certain of course that Frémon takes liberties with Bourgeois’ life-story because such liberties are the stuff of the fictionalising of experience. The narrator’s prose, and this person casts herself as Louison Bourgeois, even marks these liberties by acknowledgement of the kind of omissions everyone sometimes makes even when they are only telling their own story, even when told solely to themselves. To some commentators perhaps, this dwelling in the necessity of invention will always look like ‘soap opera’ and ‘biopic’.

Yet invention is at the heart of the kind of meaning that art suspends in front of its viewers and readers, wherein they become somwhat a collaborator in these acts of meaning and invention. For instance, Frémon has Louison tell the story of one of the prototypes of Single, one cast of the form in aluminium was prepared from a plaster machette in using the living body of her ‘assistant’, Jerry Gorovoy. Bourgeois was 68 when she met Gerry, then 25, and Frémon casts him as a sexual partner as well as model and collaborator, a point over which Jerry’s public pronouncenments remain merely suggestive and inconclusive.[5] Not so in Frémon’s imaginary recreation of events, though the prose marks (in the phrases I italicise) the fact that information is reserved from us, and even the reason for this reserve is reserved.

Jerry, who had given you everything of himself, also lent you his body for a mold. Life-sized, arching over, his long, androgynous body. You cut off the head and patched up a few details. You don’t have to tell all. It only incites gossip . … . … and yet they stop to say: You can’t do that! You can’t cut people’s heads off. Why not? If I want my arching hysteric to be universal, I simply have to chop off Jerry’s head. …

I’m not done yet. I’ll suspend the arcing body by a cable attached to its navel and let it turn slowly around. … You’ll never know if it was ecstatic. I have my own ideas on the subject. And i will continue to have them.

It can’t be known … Charcot has nothing to say about. Nor does Sigmund Freud, …[6]

Only an artist will ever free themselves of Hofmann’s sad perplexity in the front of the bolder attacks on normative forms of the ‘literal’ in autobiographical fiction and I think here it allows us to access those parts of the work of art that remain fragmentary and absent, even in the presence of an active collaborative viewing because there will always be more to be known than is simply said or even shown. Let’s take the overinterpretation in this passage that describes Jerry’s body as androgynous. That Bourgeois is aware that beheading is a metaphor for castration in psychoanalytic schemas is surely known to her. Indeed she contrasts herself in this passage as she does earlier to Artemisia Gentileschi’s beheading and castration of her father as a model of art in her most famous painting:

Do you know Artemisia Gentileschi’s Judith Slaying Holofernes? What power, what audacity: she’s at the apex of the process of cutting off her victim’s head, blood spurting everywhere. The heart of the subject. … in the process of symbolically sawing off the head of her famous-painter, father, Orazio? Give me some space, Dad![7]

Louison’s naming of Jerry’s body as ‘androgynous’ is therefore somewhat ironic since the beheading, reveals an orifice much like a vagina in the version we see in Single II. Moreover that decapitation is actively performed by the artist because the body with its head is not ‘androgynous’ enough. And I think this returns us to the arcing body of ‘Jerry-Everyone’, as she later calls it in the same passage as that I cited above. That question to which no-one knows the answer is a question about the nature of ‘ecstasy’ as a feature of art, about an art in which the body in ecstacy was the subject of all creation and creativity and women were not bound to only one form of that creativity – the production of children in reproductive sex and the monstrous image of the ever-giving but secreted ‘Good Mother’ as a reflection of the bourgeois obsession with family: ‘the Good Mother takes over; the middle class becomes obsessed with family: …’.[8]

Not so in earlier art, religious or otherwise, where the sight of the ecstatric body could be female as well as male and not be classified as mentally ill. In the end I suppose Jerry gave his body to produce art in Bourgeois that was supremely ecstatic – a vision of earthy, sexual and spiritual happiness, wherein the only equivalent of plesasure is pain and whether a woman is pleasured in particular becomes a thing of no consequence. At Salpêtrière;

All sculptures from life, a wrist, a leg, a torso without a head, the exemplary cramp, or the entire arc, a body caugt in complete seizure, a frozen moment of utter contortion.

I wonder if she’s happy. Do you know what I mean? I wonder if she’s coming. In the seizure. If the ghost lover makes her come. If she’s ecstatic. Ecstasy.

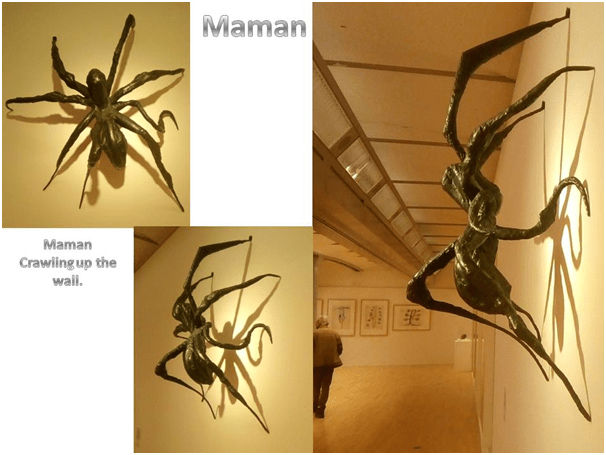

Of course ecstacy is not exactly the meaning of the French term jouissance as Roland Barthes used to continually remind us in talking about Flaubert. Who is this ‘she’ in Frémon’s text, but in Bourgeois’s enacted voice? Is it the mother freed of being at the service only of reproduction and maintenance of patriarchal family structure, somewhat like Bourgeois’s own mother who suffered her husband’s ten year affair with an in-house English governess? It was witnessing of his sexual fulfilment by her father that Bourgeois continually attributed her own later neuroses. For that is also why Single II also reminds us of the motif of the mother throughout her work, Maman, the spider, eternally given to procreation. And this is particularly the case in the example in Liverpool which is built from stuffed woven cloth, if still hanging from a mock spider-thread. For textiles and texture and touch are the stuff of the Bourgeois autobiographical experience not least because the bourgeois-ness of Papa bourgeois was based on the manufacture of textiles. And in this business, Maman Bourgeois was also brought into service of it and of the family she struggled to create in the image of the father, even colluding with the transformation of Louise into Louison, of hermaphrodite girl to hermaphrodite boy, even in dressing-up games.

And this is why I title this blog from the simplestr sentence in the book: ‘Mother was also a kind of weaver’.[9] This sentence comes from Frémon’s recreation of Bourgeois narration of her early family life and artistic theory and the role in both of these of spiders, of whom the archetype is Arachne. A mother is a nurturer and ‘Mother was the only person with whom you felt secure’.[10] Yet the dark side of the nurturer is the wronged being seeking revenge for its marginalisation too if without the means of actually achieving that revenge: ‘Mother pretended to be on top of the situation – which pretty much amounts to being on top of it if you can’t change it’.[11] Hence Maman has ‘always been in my drawings, in the form of a spider’,[12] the creature to which the jealous Minerva transformed Arachne in Ovid’s Metamorphoses when Arachne was on the point of killing herself.

… she condemned her to stay suspended at the end of her thread, then sprayed her with poison, …, that ate away at her little by little iuntil she was no more than a belly with scrawny legs, which she nonetheless kept working in order to weave the web that would be her refuge from then on.[13]

The sculptured spiders, which grew in size until they were fit for outdoor display only – for one is taller than the Kunsthalle in Vienna, is an early one in this exhibition but ominous nevertheless.

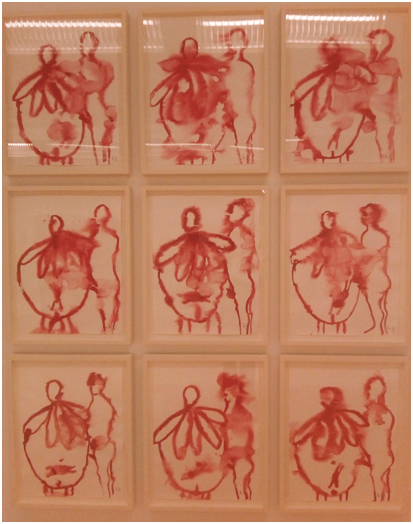

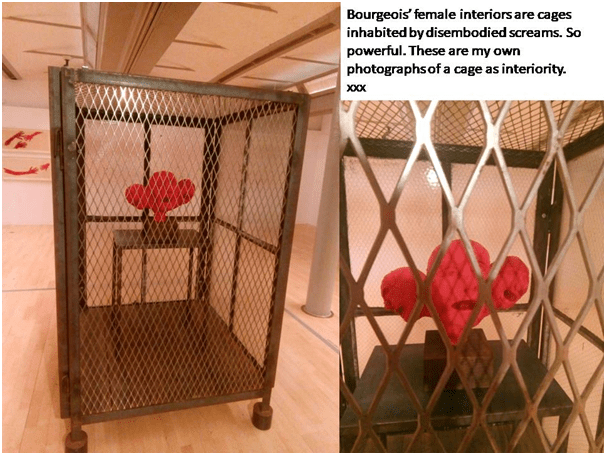

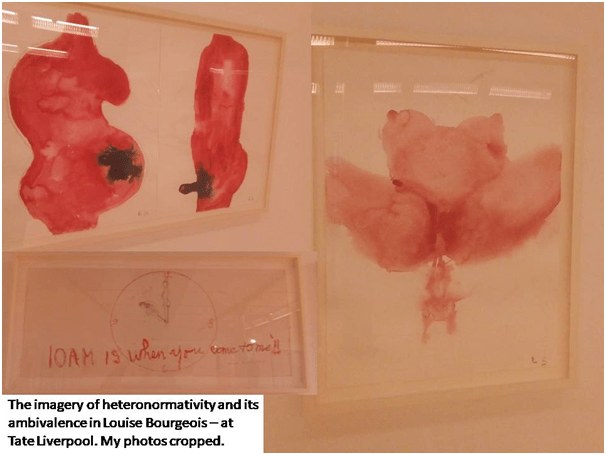

The moment of parturition is ‘conceived’ and painted by Bourgois very often and as if in menstrual blood. It as if the material of a woman’s life was already part of her body, like the threads of silk are from and of a spider’s body. But this blood is traumatically spread in the service of heteronormative families and this explains her close identification of the LGBTQ+ movement she achieved in her later life and in her work for ACT UP. The images below will stand instead of further comment on this notion which I have no right to elaborate, other than in total admiration and awe at the way in which art serves sexual politics without being just sexual politics but a queer phenomenon that stands alone.

Beyond this account of my visit to this ARTIST ROOM exhibition I only want to record how wonderful it was to see it with my friend Catherine who had no prior knowledge of Bourgeois or preparation for her art but who seemed to respond to it in a way that enlightened me as to the power of the imagery, particularly the female imagery. Some of her images work entirely viscerally as if the motor nervous system and its deep innec connections to schemas for both emotional and intellectual response. I want to finish with one such.

Of course we can give with one hand and take with another but have we ever felt that idiomatic phrase viscerally as in this ambivalent limb which enforces, presumably by some mechanism of proprioception, that we feel what a ‘clench’, ‘grasp’ or ‘open hand feels like to the nervous system. For these thoughts and feelings ar the stuff of human interaction taken back to the senses and their connection to emotion and ideas. In that sense art liberates because these are, in ‘real life’ horrible feelings. But I hope I have also illustrated that we also need Bourgeois’ ‘life’ to be conveyed equally viscerally as the body through which such combinations of cognition, affect and bodily sense first came into creative being.

Bourgeois is a very great artist. See this small exhibition if you can, it is free but you need to book ahead unless you are going to another exhibition, already booked, such as that on Freud, ‘Real Lives’, as we were. There will be more on the latter in blog LIVERPOOL 4.

All the best

Steve

[1] Frémon (trans. Swenson) (2018: 33)

[2] Freud’s Toys by Loiuse Bourgeois reprinted online in Art Forum Available at: https://www.artforum.com/print/199001/freud-s-toys-34249

[3] Christopher Turner (2012) ‘Analysing Louise Bourgeois: art, therapy and Freud’ in The Guardian (online) Fri 6 Apr 2012 22.45 BST Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2012/apr/06/louise-bourgeois-freud

[4] When I have finished The Magician(about a third of the way through currently) I intend to examine Hofmann’s case more specifically in relation to it in a later blog, but I have a lot of other projects in the offing as yet, but I will add a link here when that happens.

[5] Consider these instances: https://www.theguardian.com/theobserver/2010/dec/12/louise-bourgeois-obituary-by-jerry-gorovoy, where the suggestion of being ‘involved’ with an ‘older woman’ hangs moot and unspecified. Otherwise Jerry speaks of aesthetic collaboration only: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L2QSoecENYQ

[6] Frémon, op.cit.: 80-82

[7] Ibid: 49

[8] Ibid: 76

[9] ibid: 33

[10] Ibid: 29

[11] Ibid: 30f.

[12] Ibid: 31

[13] Ibid: 34f.

17 thoughts on “LIVERPOOL VISIT 1: ‘Mother was also a kind of weaver’.[1] This reviews the ‘Artist Room: Louise Bourgeois’ exhibition at Tate Liverpool. In lieu of there being a catalogue a fictional autobiography of Bourgeois by Jean Frémon (translated by Cole Swenson) [2018] ‘Now, Now, Louison’ is used.”