‘Plutarch reports that Philip [King of Macedonia and father of Alexander to-be ‘the Great’] saw them “mingled together” – the word Plutarch selects has erotic overtones – and was moved to tears at the sight. “Perish all those who suggest that these men did or endured anything shameful,” Plutarch quotes Philip as saying, as though moved by the thought of the erastai and erômenoi embracing in death’.[1] This is a blog reflecting on The Sacred Band by James Romm (2021) New York, Scribner.

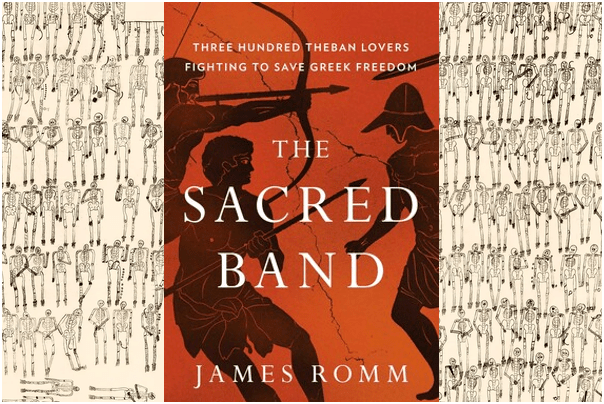

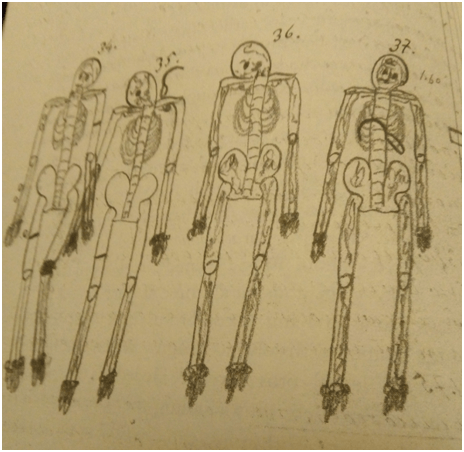

Above the front cover of Romm’s brilliant book overlays a drawing by Panagiotis Stamatakis of how he ‘discovered’ the skeletal remains of the Sacred Band of Thebes, an army comprised of loving male couples. Even in the brief ‘extracts’ visible here a number of puzzles are revealed. The bones were arranged we know from remains found on the battlefield in as whole a way as possible since many had been mutilated by the Macedonian soldiers.[2] In some places arrangement falls away and the men seem cramped together. The pattern is meant to be that of a military phalanx but space seems to have been lost as the arrangers are nearest the bottom of the space available and the last row appears in, using Romm’s words, a ‘strangely cramped and irregular layout’. Indeed some are laid perpendicularly whilst others get jammed in between other individual skeletons with overlap of bones in ‘unseemly overlaps’.[3]

Yet amongst the chaos we can see some consciously planned ordering including the fact that ‘pairs of corpses were laid out with arms linked at the elbow – a restoration in death of the bonds that linked them in life’.[4] Since none of these descriptions can be verified other than interpretations of what we see, the mass grave of the Sacred Band is surely a space in which interpretations of gay relationships are important a-priori requirements of understanding what is intended by the arrangement of the corpses and body parts here. Since we know this arrangement, or its absence was in part an effect of happenstance: for instance, the finding of the body parts occurred over a period of time and therefore, because at the offset no-one knew how many would be recovered in total, an overall plan for the arrangement was not possible. The reason for the mutilation of body parts is itself lost. Moreover, we cannot understand why and how only some of the men were, or appeared to be paired, nor how this is represented in iconographical terms and with what common knowledge assumed. Are overlaps then between bones intended and meaningful, and if so with what meaning, or accidental?

If we look for pairings as described by Romm (arms linked at the elbow), those extracted on page 90 (corpses 34 and 35) seem to be an example.

But given what we know about the contingent difficulties of spacing can the ‘arms crossed at the elbow’ of 34 and 35 be construed as necessarily intentional, to say nothing of being construed as a love pairing. We just have far too little information to make such a point with any certainty I would suggest, especially since the major difference between the pairing of 34 and 35 may be explained by inadequate regulation of the distance between each individual corpses and the possibility that proximity gave greater chance for accidental overlapping of bones caused by poor handling or the movement of subterranean soils for any reason we might imagine Compare this couple with corpses 18 and 19 where the overlapping of limbs appears even more intentional and meaningful perhaps.

How are we to interpret the meaning of the arrangement here? Corpse 19 has only one arm (his left) and it is bent at the elbow with his hand bones lying over the area where his genitals were once. 18’s right arm meets 19’s arm near the elbows but his other hand appears to have been placed just above 19’s hand. Stamatakis seems too to have invented facial expressions for the skulls which inevitably enable interpretation of how the skull and hands are disposed.

It is difficult to not see gestures, somewhat disarmingly dynamic ones, of the mobile gestures of lovers, which may or even may not be sexual. Whether they are that would have to discount that the disposition of bones was not by accident or by virtue of someone else’s need to interpret what they saw in these men without any authority to do so. Even then we cannot solve whether we have a much more sexually attached pair in 18 and 19 than 34 and 35. Nothing can be determined. Everything is necessarily bathed in conjecture about evidence that may have had little or no design behind it. Of course we know that Pammenes did, if Plutarch is to be believed, arrange the living Sacred Band ‘so that lovers stood side by side’, but did the men who arranged these bones copy this formation and if so, why so partially. Moreover given the deadness of the bodies how was a living attachment to be coded and the kind of bonding made detectable. Plutarch also tells us that Phillip was once the beloved of Pammenes but it is possible to interpret the speech of Philip at Chaeronea to show that he was aware that the virtue of male bonds was being constantly contested: “Perish all those who suggest that these men did or endured anything shameful”.[5]

This matters in that, as Romm shows the Sacred Band became evidence of the deep history of male loving unions to the early movement for the recognition of male sexual relationships in the nineteenth century and after. As the review of this book, summarising Romm of course but in a rather starker and more anachronistic language, in the History News Online Journal says: ‘It’s the first we hear, in any Greek city, of a legislative program designed to encourage same-sex pair bonding; some other Greek law codes explicitly discouraged it’.[6] But to move from this to endorsing the views of Walt Whitman or George Cecil Ives about their historical significance in the history of male queer sexuality as a social phenomenon, and the proof of the possibility of a queer Utopia modelled by Thebes, is a big step. Plutarch’s account has always been considered by some anyway as nearer fiction than fact. We are left at the end with the problem of interpreting what was the source of the idealisation of the Sacred Band: modern wishful thinking projecting itself backwards into history or an ancient example of a human potential that is always present through time of love (and perhaps sex) between men if not universal for all men at any of those times.

It is an old question. Benjamin Jowett considered this love as a matter of purely mental union between men and eventually as a merely a metaphor for the role of feeling in the intellect and even Walt Whitman refused to acknowledge that he really was talking about sex between men when he had ‘a dream of a city in which he saw men ‘tenderly love each other’.[7] I think the point is that there is only support in history for a continuity of non-normative (I prefer the term ‘queer’) alternatives to any norms that may have had some hegemonic role in society and there is none for the existence of model utopias supportive of a historical construct of the ‘homosexual’ or ‘’third sex’ as a normative stable variant.

Alan Contreras reviewing the book for The Gay and Lesbian Review says that it matters to our sense of LGBT history that not did ‘a homosexual military unit’ exist, but that it was not ‘considered strange’ by contemporaries. In short it was one of many possibilities in which humans could legitimately organise outside norms. But he also says that the book gives no support for a notion of ‘homosexual identity’. As Contreras says, it is neither a book ‘mostly about gay warriors’ nor does it offer ‘a lot of detail about how these men actually lived’.[8] It is about the contingencies in which those men existed although we remain ignorant of anything that is that usually constitutes the stuff of identification between people. And, in truth, the book is as much about how that these men constituted as a force in the defence of the Theban state and putatively (and debatably) ‘Greek freedom’, since Thebans were capable of any kind of alliance against Greek neighbouring city-states too.

Their existence however becomes the focus from Classical Greece onwards of debate about the social meaning and possible purposefulness (or its opposite) to the politically and socially constituted ‘polis’. This debate occurred for the first time accessible to us between two former schoolmates, Xenophon and Plato. Xenophon even refused to use the term, ‘Sacred Band’, preferring instead ‘the “chosen men” of the Thebans’ and then only mentioning them once. How different this from the later historian, Plutarch, who was born a Theban.[9] Romm argues that Xenophon’s attitude can be traced to his interpretation of the need in Greek military men to a quality he saw primarily as rooted in the Spartans, enkrateia (ἐγκράτεια) or self-mastery. He attributes the attitude to Socrates who he pictures in his works as very different from the representation of the philosopher in Plato’s work.[10]

Plato himself does not mention the Sacred Band, although this may be because his Symposium is set at a date before its formation (as Romm tells us) wherein Phaedrus refers to a putative ‘army of male couples, in a city where men could be “wed”, as in Thebes. Some scholars argue that Plato intended to refer to the Sacred Band in the words of Phaedrus. Other speakers moreover, including Plato’s Socrates’ maintain, the dignity of relationships between the erastai and erômenoi though only by insisting on their bodily purity as lovers in which their love brings them ‘toward higher, nonphysical truths’. We know such relationships now by the term Platonic love.[11] Here again then self-mastery rules but Phaedrus story of the city of male lovers, almost certainly used by Whitman as a source for his city of male lovers, does not exclude sex and Plato, unlike Xenophon, seems capable of contemplating this possibility even of only as a point of resistance for truly philosophical lovers. We can see how from both Plato and Xenophon, Benjamin Jowett may have crafted the notion that love between men is perhaps only a metaphor without invoking Jowett’s own asexual life. His students however did not follow him on his path necessarily, preferring instead the way these relationships would be conceived in the art of Oscar Wilde who called the hero of his key novel, Dorian, for a purpose. In 1873 John Addington Symonds was lauding the ‘military aspect of Greek love’ in his low-distribution pamphlet A Problem in Greek Ethics.

The extermination of the Sacred Band at Chaeronea can be laid at the door of Alexander, the son of Philip who completed the humiliation of Thebes and saw the conquest of the Band as central to this purpose – especially in establishing hegemony for Macedonia in Greece. The killing and desecration was almost of a ritual nature for Alexander knew the power of male Eros. The killing resembled the most violent kind of male upon male rape.

Spears penetrated so deep as to be hard to pull out: some victims were found with blades still lodged in pelvises and rib cages …/ … One man’s facial fractures indicate he’d been hit by a heavy object swung up from below, …. That must have killed him, but only after his skull had been bashed in from above and partly sliced by a blade at the back of his head. This man, battered from all sides, had been unwilling to die.[12]

But the respect for Eros as a fighting force that must be ritually murdered in Philip and Alexander as victors was not shared by all. The native Theban tradition of ‘male erôs as a long-lasting privileged bond’ was not revered or respected by all, though it is by Plutarch. As we have seen Xenophon disrespected the tradition as insufficiently Spartan in type and ‘tried to prove that the Sacred Band were cowards, not heroes’, since, he reasoned, a couple of men in love were more likely to flee than embrace the honour of battle, irrespective of the desire to look good in one’s loved one’s eyes.[13]

The importance I’d suggest of the Sacred Band to queer history is precisely that it allowed queer loving practices to become a much richer object of social policy than was otherwise possible, however much it was also simplified by nineteenth century notions of the ‘homosexual’ as an individual type. Whatever, this is a gloriously liberating and beautifully written book. I heartily recommend it. We should feel like King Philip, that all should perish ‘who suggest that these men did or endured anything shameful’ but we must also be as clear as Philip may have been necessarily vague that consensual sex between men does not constitute something that is shameful to DO or ENDURE.

All the best

Steve

[1] Romm (2021: 241f.)

[2] Ibid: 243

[3][3] Ibid: 242f.

[4] Ibid: 244

[5] See ibid: 242 for this paragraph

[6] See https://historynewsnetwork.org/article/180453

[7] See Romm op.cit: 64f.

[8] Alan Contreras (2021) ‘The Theban 300 in Love and War’ in The Gay and Lesbian Review XXVIII, No. 5. (September-October 2021), 35f.

[9] Romm op.cit.: xvi

[10] Ibid: 67f.

[11] Ibid: 112

[12] Ibid:240f.

[13] Ibid: 75

Well done Putha its well written, please try to edit your work before posting,you keep missing punctuation and capital letters.Very spooky blog lots of Halloween 🎃 fun.Amma x

Sent from Yahoo Mail on Android

LikeLike

Too true Maya. I try to proofread but miss it all the time. retirement has taken off the edge I once had to care about punctuation. maybe i just love error! Lol. Thanks for your comment.

LikeLike

Philip II’s words about the members of the Sacred Band not having suffered anything shameful had nothing to do with the fact that they were male lovers, as this was also common among the Macedonian elite (Philip was even killed by his lover, Pausanias, and Alexander loved Hephaestion and other men), but rather that the defeat they suffered should not be seen as shameful, as Philip as a teenager lived with the Sacred Band, he lived in the house of one of their commanders (Pammenes), so they were men very dear to him.

LikeLike

Fine. But I think this is an addition to the reading not a subtraction. But, of course, I may have it wrong. Always grateful for pointers. X

LikeLike

When Philip said that the men of the Sacred Band did not do or suffer anything shameful, he was referring to their having been defeated in battle, not because they were same-sex couples (this would not make sense, since male love was also seen as natural by the Macedonians, Philip himself had male lovers and was killed by one of them, Pausanias, not to mention his own son Alexander, who always had his beloved Hephaestion by his side, who certainly also fought at Chaeronea).

LikeLike

But this is an argument that the book contests in an interesting way. I think I found the argument convincing. But have a look. Long time since I read the book, so I can’t engage in debate, but thanks for interesting comment.

LikeLike