A reflective visit to the Art Gallery in York makes me think about how much we owe to examples of excellent curation practice in ‘provincial’ museums to save us from having our reflection about art done for us, with whatever authority, by art history alone. This is an account of a visit on the morning of 11th September 2021 to see a FREE exhibition of Japanese Ukiyo-E Prints at York Art Gallery. However, in writing it became an opportunity to reflect on japonisme in England. Yes, England, rather than in ‘Van Gogh’s work’, Scotland or elsewhere in the great education-loving non-Brexit voting mainland of Europe, says he (with tongue-in-cheek, PERHAPS!).

First of all let’s allow the gallery to speak to us. The first quotation outlines why the gallery consider this version of a show of these already celebrated forms of art important before I elaborate on my motives. They will also speak for a second time from a readable photograph of the information printed on the one-room gallery in which this free exhibition takes place. At that point the curators give the facts from the history of art in Japan on which it builds its gift to us of a very fulfilling and exciting exhibition. So here from their web-site (as pictured above), although I have added links to Wikipedia introductory elaboration of certain art-historical terms and artists’ names:

A new display featuring rarely seen Japanese Ukiyo-e prints alongside much-loved paintings from our collection will go on show in a new Spotlight Series celebrating the reopening of York Art Gallery next month.

‘Pictures of the Floating World: Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints’ will feature prints by prominent Ukiyo-e artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige, along with works by those influenced by Japanese art, such as public favourites Albert Moore and Walter Greaves. This unique display will highlight the significant impact of Japanese art on the western world and the consequential rise of artistic movements such as Aestheticism and Art Nouveau.

“Ukiyo-e translates as “pictures of the floating world”, referring to the transitory nature of life. Visitors will see delicate prints depicting scenes celebrating everyday life, through themes such as landscape and travel, actors and courtesans, and folk tales.

This show will delve into the history of the works, explaining why Japanese art became increasingly influential during the 18th and 19th centuries. With the variety of artwork on display, visitors will see how western artists were inspired by the use of line and colour, and how Japanese artists were influenced by western artists’ use of shading and perspective.[1]

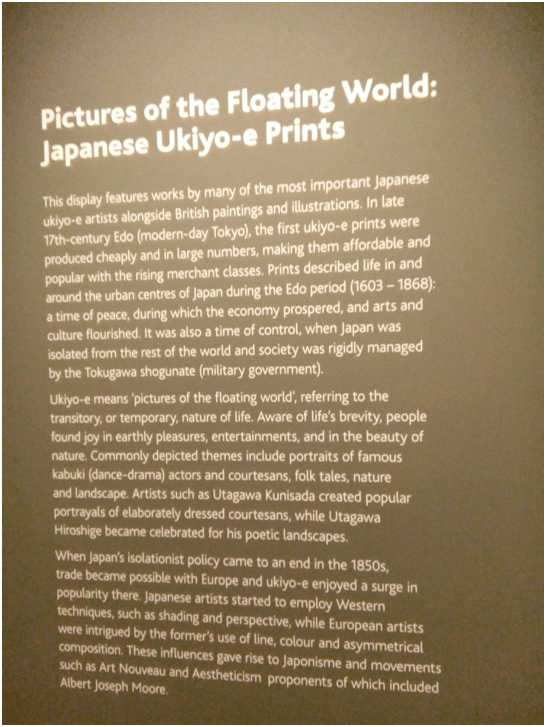

The delving into history begins as we enter the room in which the show occurs by way of information printed on a wall, which to save my typing finger I photographed. Here is my photograph:

Pictures of the floating world then were really about what it is like to live in a temporal space whilst being aware that it will pass however we respond to i. In the West Romantic artists tried to capture and hold the world, almost as if in one of the camera obscura visual artists, according to David Hockney at least, increasingly used to ensure a fixed perspective from the gaze of a solitary eye. Even the poetry, with rhythms that so easily turn into soporific heartbeats attempts like Wordsworth to render it still (both without motion or insistent sound effect):

I have said that poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings: it takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquillity: the emotion is contemplated till, by a species of reaction, the tranquillity gradually disappears, and an emotion, kindred to that which was before the subject of contemplation, is gradually produced, and does itself actually exist in the mind.[2]

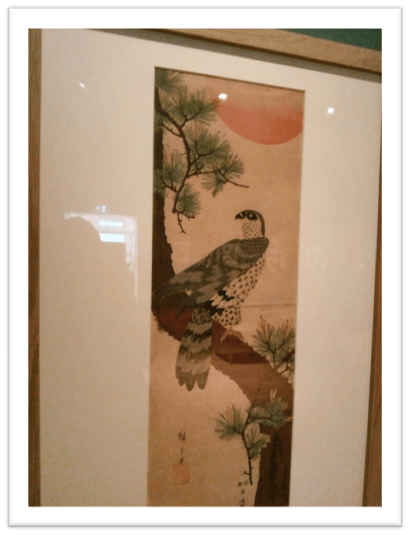

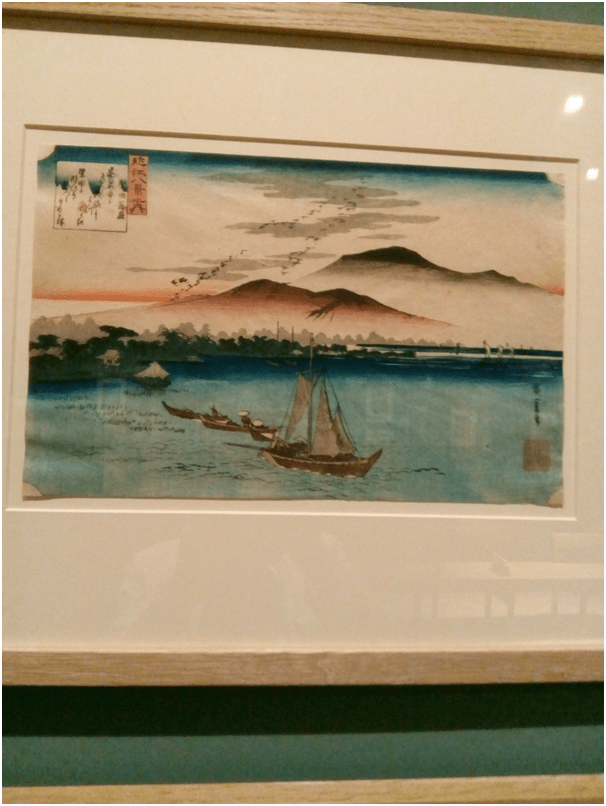

This was never the feel of Japanese Ukiyo-e Prints, which insisted that beauty and pleasure were too short-lived to be merely reflected upon. They must shout at through their command of empty space, colour and costumed gaiety. This is an art of clothed and adorned beauty, as akin to acting and role-play as to nature, which anyway is grasped in artifice not as it actually appeared, with all the artist’s attempts to enhance its beauty plain and even commented upon. Subjects take up empty spaces, where these spaces are not also adorned with the pictographs of Japanese or Chinese script, as in this beautiful moment in a Utagawa Hiroshige print of a hawk collecting its wits in the shadowed space coloured to match a red sun.

It is not only the presence of text that encourages us to both speak this beauty aloud and sense the visceral motion that will follow the temporal stillness, it is the alertness and purposive visible in the hawk’s eye, which arrests us lest it fly too early and away from us. The same point about the presence of motion might be said of the remarkable print in this collection: The Waterfall of Nikko Zan in Shimotsuke Province (1853).

Examining this print keeps the eye restless as a result of the need to follow the motion of the main water-course until it begins to fall as a torrent. The degree of stylisation here means that thje eye selects and follows patterns that get repeated in other lateral falls. All this is compounded by the lack of a singular perspective since the eye both looks down upon the landscape from an impossible high viewpoint whilst also seeing the figures on the path under the waterfall as if from a more lateral viewpoint. Other vertical falls are equally stylised. The eye is driven down by the sheer volume of the blue. The viewer’s eyes follows then the water in both space and time, an effect Clive Adams sees as intrinsic not only to Chinese scroll painting but also Ukiyo-e artists where the apprehension of passing time, usually in the form of bustling urban landscapes, was more important than giving the eye a controlled command of spatial relationships. There is something almost dizzying about the perspectives on this waterfall. This is in part because these artists are highly selective about what visual features to include. Here only the immediate environs of the watercourse seem to interest the artist until we meet the pass across and behind the waterfall where people might come and go. As Clive Adams also says this is at its most appropriate ‘to express urban life in a rapidly changing country’.[3]

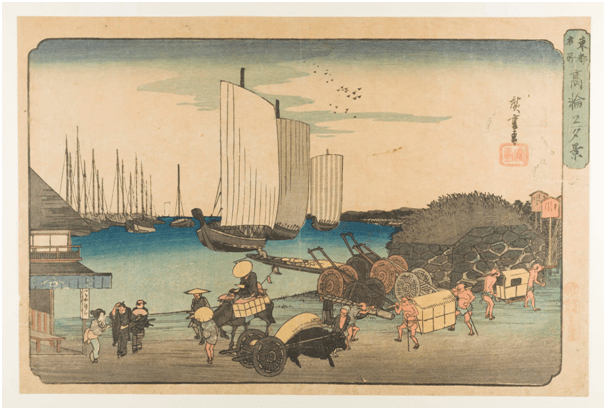

A picture of a harbour front reveals what this means. Adams sees this perspective as that of disembodied beings ‘between angels and beasts’ that commands parallel perspectives both ‘aerial’ and linear over a complete panorama. We struggle between the details of buffalo or a trading conversation on the shore side and a long view out to sea, the source of the trade causing quayside bustle.

It is these features, including a non-realistic use of patches of colour, that characterise the work the York curators ask us to compare to Hiroshige, most successful in the case of G.F. Watts View of Naples Bay which compares directly I think to Hiroshige’s view into Edo (Tokyo) from the sea .

Of course we can take the comparison too far unless we sense that Watts could have learned the use of high perspective too from Turner but there seems a nearer comparison between Steer Wilson’s and Hiroshige’s quayside views.

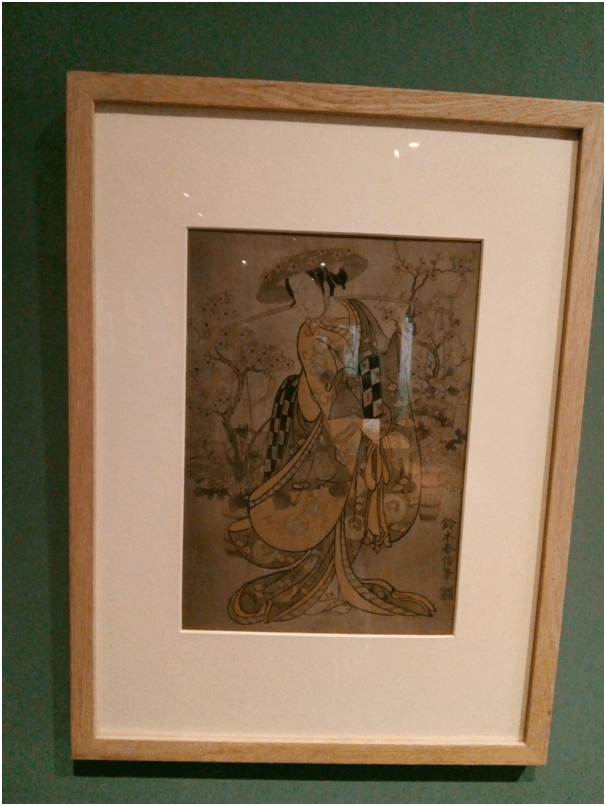

There are other analogues here too but that is less the case when the topic is clothed beauty. The Floating City is a world of role-play by both actors, performers (such as wrestlers) and courtesans or geishas. Sexuality here is bound not in visible bodies but in the motion of gesture in clothes that completely cover the body, capturing the eye in the dynamic swirl of folds.

There is a courtesan. Here is one from Utagawa Sadatora where it is the loosening and slippage and screening of purpose that makes the painting so full of motion and action, and the eroticism bodily without any skin surface being exposed.

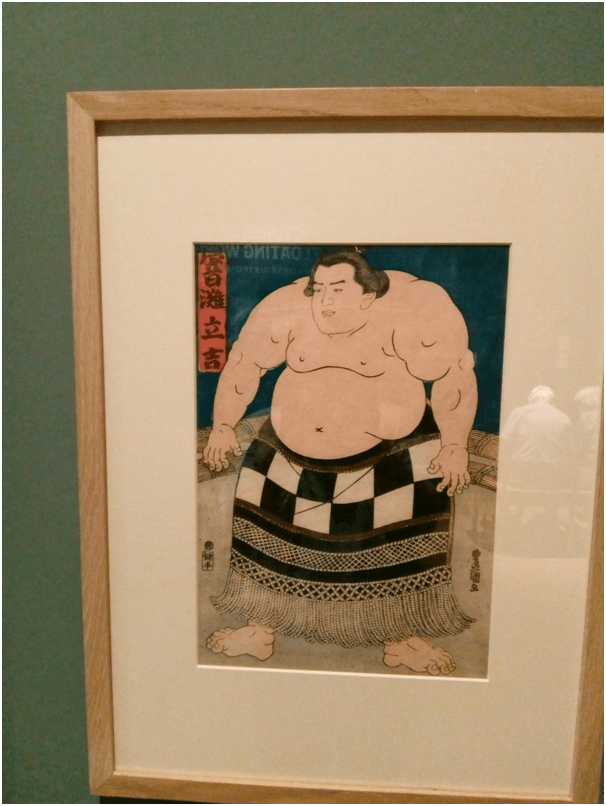

And so too with performers captured by the genius of Utagawa Kunisada (1786 – 1865).

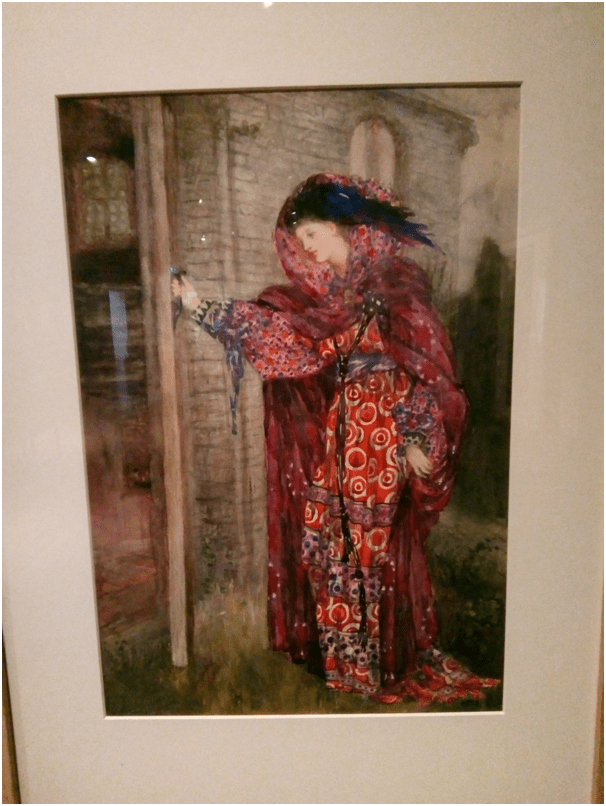

Outer and inner action are all implicit and complicit – sometimes in tension, allowing for a reserve of excitement. It is this perhaps which makes this Hart Crane boldly comparable to a Hiroshige courtesan. The excitement is in the bustle of the unclothing to get to the source of the motivation towards colour and vibrancy. But even I feel that may be pushing interpretation too far.

Sometimes there is no tension between body and body attitude and gesture, as in this sumo wrestler, complete and contained in his vast but comfortable body.

I think the reflection I came out of this exhibition with is that curators can leave interpretation to viewers by just leaving comparisons they make to the varying judgements and susceptibilities of viewers. After all error here costs nothing and can increase interest. no-one is for instance aiming to pass an exam at the end of a visit.

We also know that japonisme was a means by which art took to non-realistic composition of the surface of canvases, and thence to abstraction. We can take these comparisons as far as we wish but it is exciting not just to apply them to Cezanne and Van Gogh. It is exciting to look at English painting, as is already done with Scottish greats, as it struggled with the opening up of trade to Japan as much as any of the continental forms.

Go and look for yourself. You won’t regret it. York is lovely now anyway. All the best

Steve

[1] Text from web-page available at: https://www.yorkartgallery.org.uk/exhibition/pictures-of-the-floating-world/

[2]See the term sourced and elaborated at: https://interestingliterature.com/2021/02/wordsworth-spontaneous-overflow-of-powerful-feelings-meaning-analysis/

[3] Clive Adams (2003: 16f.) ‘Between the Angels and the Beasts’ in The Impossible View? Salford Quays, Manchester, The Lowry Press.16-23.