A blog reflecting on a Futurelearn Course led by Sarah Stewart:

Zoroastrianism: History, Religion, and Belief, SOAS University of London, & Sarah Stewart (ed.) [2013] The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination, SOAS, University of London with The British Library & I.B. Tauris, London, New York, the catalogue of a SOAS exhibitionIn Brunei and London in 2013.

It is rare for me to be so astonished by the thoughtful pedagogy in distance education MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) these days so this course took me by storm, saying in a comment on 28th July 2021, after having some hesitations about my total lack of knowledge and taught skills in the areas introduced, including the language Avestan, that:

In fact I am progressing fast through the course because I admire its intentions, methods and style – and of course the material. It is I believe one of the best taught course I have done. Thank you both..

I even found the courage to write my own first name in Avestan as part of the introduction to the script of that language and limited version of useful vocabulary and grammar of that language.

I can’t then recommend it enough. It is much more comprehensive than my account of the other materials here and pays off in buckets as you begin to feel your way around a still living culture and tradition and the changes that occurred within as a result of alliances with great Persian empires (those that battled with Classical Athens), contact with traditions of the Jews and Christians over a long period, marginalisation after the success of Islam in Persia and a wide Diaspora, staring in a fabled migration to the north west coast of India, where the Parsi tradition grew up as represented in the Qesseh-ya Sanjan. That text is, supposedly, written in 1599 when a sustaining myth of the continuation of Zoroastrian community, ritual and history was necessary and represents the migration as a single mythical event. In fact as the most recent translator of the text, Alan Williams, says in this book the migration ‘even’t to the Gujurat coast was actually probably a lengthy process in itself within the longue durée of history.[1]

For me coming to this course was a revelation of my ignorance of vast swathes of ancient history. I knew about the Achaemenid Imperial dynasty of Persia from Aeschylus’s play The Persians and a little about Parsi Zoroastrianism from being an early reader of Rohinton Mistry’s novels which involve the diaspora Zoroastrian community. But even here my ignorance was legion as shown in this contribution from the 27th July:

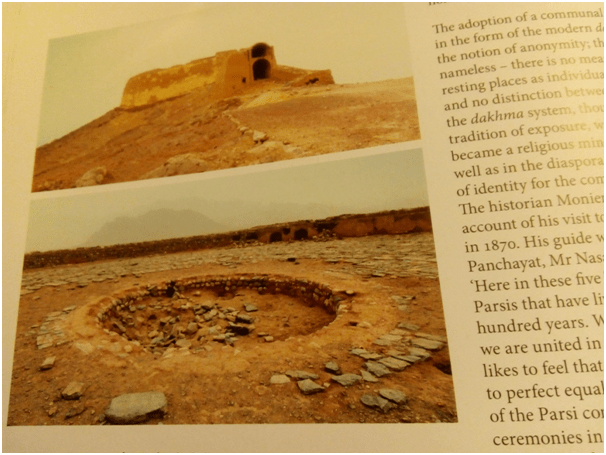

In another Mistry novel Such A Long Journey there is reference to the Towers of Silence and debate between the whole diaspora of Zoroastrians. Look at this passage. It may be a bit sly (this point of view from within the date I meant) but I take it that Towers of Silence – where the dead are eaten by vultures – were a Parsi innovation based on the principle of purification and non-contamination of the earth. Or did Towers of Silence come earlier.

“The orthodox camp for vulturists, as their opponents called them, countered that reformists had their own axe to grind in legitimating cremation: they had relatives in foreign lands without access to towers of silence. Moreover,

the controversy was a massive fraud cooked, up by those, who owned shares in crematoria, they charged: the chunks of meat were dropped on balconies from single engine aero planes piloted by shady individual on the reformist payroll. (317)”On that note compare this news item from ‘The Guardian’ in 2015:

https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2015/jan/26/death-city-lack-vultures-threatens-mumbai-towers-of-silence

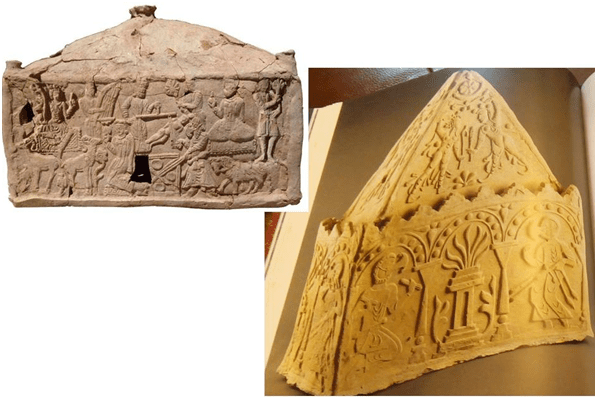

In fact I only had to read on further in the course to discover discussions of the evidence or attestation of the origins of the exposure of the dead as a Zoroastrian practice or to read Stewart’s illuminating chapter in the catalogue which traces reference to the dakhma tombs and the difference between the preservation of human remains in the practices in the Young Avestan text the Videvdad from modern practice. For instance bones from bodies from whom flesh had been consumed by carrion animals were in early practice kept in elaborate ossuaries, whereas in the instance in the photographs they were swept into a communal pit in the centre of the tower structure (see above). The relief illustrated ossuaries of the earlier practice are indeed a source of knowledge of early practices and beliefs about the judgement (weighing in fact) of an individual’s good against his evil deeds. But the answer to my question is that though there is little to attest to the practice in Iran, the absence of certain memorial evidence may still point to exposure of the dead and that the other evidence is from regions – the ossuaries are from Chorasmia, for instance, where they accompanied burial practices from other religions, as they continue to do in the Islam of the modern Chorasmian region (Grenet 2013: 98).

This is too complex an area for a novice (and only barely that) to comment upon, although the two ossuaries shown seem to have more interesting differences than common points, even given the common shape, up to a point, of the caskets. Indeed as I try to collect my thoughts I wonder whether for the absolute beginner, more contextual background is needed of the timeline of Persian history in order to place the archaeological and textual finds, such as the appropriately intellectually simplified one that this link connects to and that has helped me. I’d also relish slightly more informative geographical-historical maps, although I found following the chapter on ‘Imperial and Post-Imperial Iran’ by Jenny Rose and Sarah Stewart was helped by finding the key place names on the prefatory map offered (see below).[2] Nevertheless, given that academic sources so often cast doubt on the reliability of Wikipedia accounts and illustrations, I feel the need for a substitute to this ‘source’, which I nevertheless used.

Of course beginners ask too much of specialists and the strain of the course, exhibition and book of the exhibition is less on the conveyance of the facts of ancient Persian history from the Babylonian Empire and its Fall to the Arab Conquest and the Diaspora up to the present day, as the examination of ‘myth’, as defined by the course and the book. The best definition is in Alan Williams essay and illustrative of the rich literature of the Avesta and the changes in the content and form of the mythical stories according to the needs of a present population with very different priorities through history. The simple and beautiful founding myths of the Gathas for instance clearly would not do to characterise the temporal and spiritual theocratic power meant to be represented in the Achaemenid or Sassanian Empires and their capital cities. And in the complex continuing history the myths needed by a global population in Diaspora world again need interpretation. This is particularly so when populations are hosted by different populations and colonisers, such as in later Parsi history the mercantile British. New values need to add nuance the simpler separations of good and evil in the Gathas. Williams defines myth as ‘a story of great value that conveys a transcendence of historical time and interweaves strands of meaning to convey something of collective significance’. [3]

And the course makes vital points about taking into account the perspective on Zoroastrianism that is used to interpret it – whether that of an outside and external view or an internal one situated in its own time and space. It takes us through the different kinds of literature supporting the religion and eventually to the languages that supported them and interpreted them, from original ‘hymnal’ myths to exegesis in later texts and elaborations (of ritual in particular). The chapter by Almut Hinze on ‘Sacred Texts’ is superb.[4]

What I needed here was some consideration of the genre of these texts and a way of understanding how graphic illustrative art related to text, by when Hinze offers so much, that is greedy. Nevertheless there are fascinating comparisons between the use of fire imagery in Zoroastrian literature and illustration and in the adaptations from these myths in the religions of the Jews and Christians. Hell became popular in Zorastrian thought when the threat of conversion to host colonisers or nations to which the diaspora emigrated, although the Parsis accommodated themselves to Hindu and Christian religions in India, with separation around ritual mainly (as is clear in Rohinton Mistry’s novels) but it was a different hell – one where the scorn of the faithful is like ice, and it is compared to Dante’s Inferno bu Stwart, Ursula Sims-Williams and others, where the pain of hell is fire (unthinkable to the Zoroastrian).S. Stewart [ed] op.cit, p. 146

Perhaps the only thing I disliked about this book 9and this is the niggle of a committed Republican) was the choice of having a foreword by Prince Charles, which seemed more reductive than anything else in book, course, exhibition or catalogue. But maybe that sells books and links national institutions. Thus power maintains itself. However, this is a highly recommended course, and book, in every which way.

All the best

Steve

[1] Alan Williams, (2013) ‘Looking Back To See The Present: the Persian Qesseh-ye Sanjan as living memory’. In Stewart, S. op.cit. 50 – 57

[2] In S. Stewart [ed.] op.cit.: 112 – 137

[3] Williams (2013 op.cit.: 50)

[4] Almut Hinze (2013) ‘Sacred Texts’ in S. Stewart [ed.] op.cit.: 82 – 91.

3 thoughts on “A blog reflecting on a Futurelearn Course led by Sarah Stewart: ‘Zoroastrianism: History, Religion, and Belief’, SOAS University of London, & Sarah Stewart (ed.) [2013] ‘The Everlasting Flame: Zoroastrianism in History and Imagination’.”