‘…, I must talk about my body as black, and my body as male, and my body as queer. I must talk about how our bodies can variously assume privilege or victimhood from their conflicting identities’.[1] ‘It is 2004. Terrifying stories have been leaking out about the violent homophobia on the island. … In 2006 it will culminate in an article in Time magazine declaring Jamaica ‘The Most Homophobic Place on Earth’. … // This is a truth – a difficult and complicated truth: the place where I have always felt most comfortably gay is in Jamaica. In Jamaica, I know the language and the Mannerisms of queerness. … In Britain, my black body often hides the truth of my queerness’.[2] What truths does my body withhold? Reflecting on Kei Miller’s (2021) Things I Have Withheld: Essays, Edinburgh, Canongate Books Ltd.

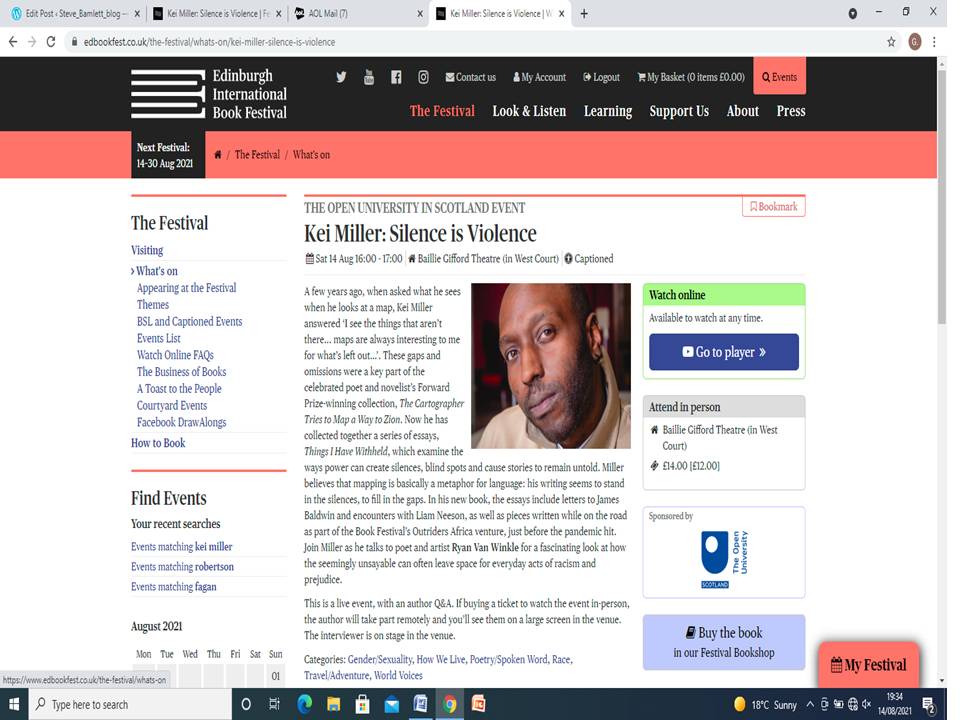

Edinburgh Book Festival addendum.

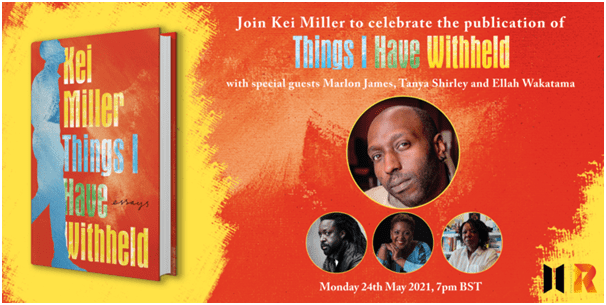

Geoff and I had the good fortune to be in the live audience for this event. Though I was disappointed not to see Kei Miller in person but rather zoomed from Miami, it was great to see his warm face beaming from a large screen as he explained that he liked to write from a ‘position of love’. Not many men can say that kind of conviction that Kei Miller has. Here is the link to the video of the event (‘Silence is Violence’) that we saw this afternoon. just after the introduction you can see me waving my arm and his book behind the presenter (a rather good one). I also ask a question about the ‘Fear of Stones’ (mentioned in the article below), which will be on the end of this piece. It is never disappointing to see this wonderful writer. Never.

Follow the ‘Go to Player’ instructions from the link below but you would need to register -although you can watch it for free:

______________________

Original piece

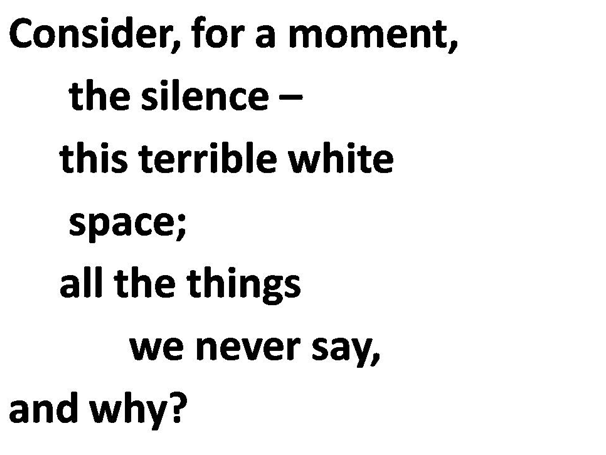

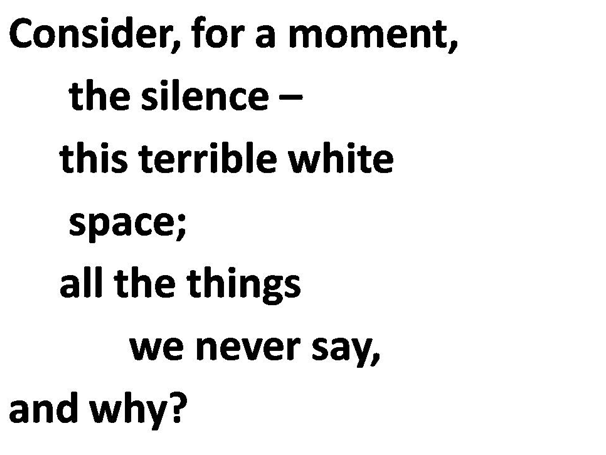

These essays are terribly urgent ones for readers ‘racialised as white’ (to use the term favoured by Sebastian Brown, one of Miller’s most appealing character types in the essay ‘Mr Brown, Mrs White and Ms Black’).[3] Without them too much will continue to be held back (‘withheld literally’) from the ways those ‘racialised as white’ of what voices ‘racialised as black’ (which Sebastian Brown likes because it includes his own and his mother’s brownness) are currently saying when they say ‘Black Lives Matter’. There is a need before more people die of the silence so characteristic of white privileged spaces. Read the wonderful poem with which the collection starts:

Black texts on white space is a commonplace format for textual reproduction, but consider what happens when the words white and back become available in ‘racialised forms’ that speak of the privilege of one culture over another. Then every voice racialised as black, and what it attempts to communicate, becomes swamped by non-communicating space as a given of the prevailing circumstances of publication, a kind of silence that represents what black voices won’t ‘say’, in Dionne Brand’s words, to a ‘largely white audience’. These words of Brand’s are referenced by Miller almost insistently as a rhythmic marker of the burden of his essays. Although white people may consider, because unvoiced and ‘silent’, things unsaid by themselves and black people as insignificant, in fact they are quite other: ‘And quite possibly the most important things will be the ones that I withheld’.[4] So these essays are about breaking into white spaces and speaking what is not thought to be worth saying or seen as a misrepresentation. And white people accusing black people of exaggerating the historical weight of ‘white privilege’ and the extent that racism matters in history are everywhere quoted in this book.

Thus a white Jamaican female writer spoken of, but unnamed, in Chapter 10 simply ‘hasn’t given herself access this (uneducated black) man’s voice, or given the man access to his own voice and his own possibilities’. Yet Miller, more importantly has to withhold these criticisms precisely because of how the white woman shows sensitivity to ‘people like me’, that is black male Jamaicans writers, ‘reading her book and throwing words like “appropriation” about’. And he will then say nothing of this because he fears, on good evidence from what is cited, that she ‘would see me as yet another tall, black man attacking her and questioning her rightful place in this world’: ‘so I say nothing’.[5] There is a brilliant attack on white excuses for racist comments based on having no racist ‘intention’: ‘I have grown so weary of intentions – the claiming of them and the denial of them’.[6]

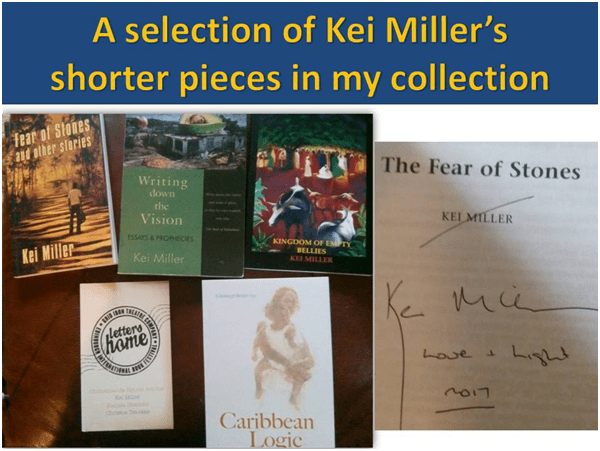

Not that this tone is new in Miller’s writing. In a beautiful much earlier essay he reflected on how as a lecturer in English literature he demanded nuance of his learners but noticed that the same argument was sometimes turned on black writers, like Chinua Achebe when they called out the ubiquity of oppressive racism in white people:

They wanted another truth – for Chinua Achebe to expand on the point that not all white people are racist. … But not all truths are equal, and it is sad when nuance is co-opted so that some of us might get away with only facing the less important ones.[7]

In the same essay he faced the difficult truth that rightful distaste for the oppression of queer men (or battymen in the patois) in Jamaica can be used as a means of denying the superior truth of a kind of ‘unintended’ racism of white people. The liberal white woman he almost, but not quite, challenges that I referenced above merely assumes that the tall body of black men might contain a hard to remove sexism and homophobia but this belief in the danger of these bodies is encapsulated in the present use of sus laws as I have already pointed to in an earlier blog on Caleb Azumah Nelson. That earlier blog is on a book that also references Kei Miller’s work as an influence but which in fact relies on their common experience of a kind of racism lodged in white bodies that resist being called out and named and defends that privilege on the grounds of other oppressions, which are actually always truths intersecting on racism. Now, Miller has himself a history of exposing homophobia in Jamaica.

It is the base of a short piece published and performed at the Edinburgh Book festival in 2014 (I was in the audience), England in a Pink Blouse, wherein a Jamaican boy ‘reach to England in a pink blouse’ to escape ‘anybody he know from Jamaica and ‘he swing his hips wide off that plane like he was reaching home for the first time …’.[8] It is one of the organising motifs of his second set of published stories in 2006 Fear of Stones and other stories. The title story concerns Gavin who is first called out as a battyman because he, urged by his young peers as boy to prove his manhood, throws stones ‘like a little gyal’: ‘Him throw like a big battyman’. Miller gives the fear that develops the term it has in a list of phobias – lithophobia.[9] But later the fear that it represents generalised beyond simple phobia to represent the fear of primal alienation from his culture that is based on incidents in which queer men in Jamaica were claimed to be stoned to death and which Miller in 2006 validated as a possibility that goes much deeper than mere fear of painful death of the physical body:

What is the fear of stones – no, the fear of being stoned? What is it called, this expectancy some men carry in their backs that there are people out there, so righteous and exact in their hatred that they will pick up a stone and fling it after us – an accusation, a punishment, a curse for not fitting in, for not belonging to some tribe they have decided all men must belong to. Is there a name for the premonition lurking in our blood that one day friends will turn their backs on us and families will disown us? There is no single word for such a thing, but such a thing does exist.[10]

Yet by 2021 Miller has become suspicious of why the claim of Jamaican homophobia, coupled with horrific stories of stoning to death retains such power (a claim that is still made in the US LGBTQ+ press), but the examples in these new essays come from Scotland or England. Has experience shown us that loss of Black Lives Matters only when, in the eyes of dominant white culture they appear to be lost by violence that occurs within black communities and between Black bodies? In one instance a white woman, attuned to homophobia in other countries, sees Kei Miller (a queer Jamaican black man), as an example of such prejudice from the evidence that he is humming along to a reggae song.[11] In another moment he cites a young white journalist who uses violence against gay men as a means of querying the right of Jamaicans to celebrate their political independence as a nation:

He had read about gay Jamaican men who have been run out of their houses, or who have been stoned, or who have been chopped with machetes and killed. Some have been lucky enough to jump on a plane and seek asylum elsewhere.[12]

Of course Miller says this to assert though, though these matters the white journalist has read happened and may still happen, that the future of independent Jamaica will in three years after the date of this story provide more evidence to support the continuing existence of homophobia in that nation and of a strong and effective challenge to it, with the advent of Jamaica Pride and a considerably stronger voice for Jamaican LGBTQ+ people.

The point is not that this journalist, writing for a white LGBTQ+ journal, is wrong about the continuing historic oppression of queer people but that his use of facts serves racist ends he didn’t intend. But having the best intentions does not exonerate him. And that is because he forgets the persistence in white cultures of the image of the aggressive sexist and homophobic black man that no counter-evidence is ever used to challenge. It is also a fact Miller will say, that:

… the place where I have always felt most comfortably gay is in Jamaica. In Jamaica, I know the language and the Mannerisms of queerness. … In Britain, my black body often hides the truth of my queerness’.[13]

And another fact is that even the most liberal, and in their own eyes politically aware, of white people are continually reproducing the basic myths of the male black body as innately and fundamentally an instrument of aggression, even against other black men: ‘Too often the meaning that my black, male body produces is ‘guilty’ and ‘predator’ and ‘worthy of death’. At the time Miller says this, he is finally recounting one small detail of a story he otherwise mainly withholds: the story of his breakup with a long-standing white male partner. He had said in his preface that the essays he writes now are ‘not about that awful relationship’.[14] But at this point this suppressed and otherwise withheld story is used to point out that he, for a time, believed he could never again have close relationship to a gay man who is white precisely because myths associated with black men were being used against him. Used by someone who once professed love to him but, in anger it is true, now claims that he has the power to ensure Miller’s deportation:

In that moment (I am sorry but this is true) I thought I would never date a white man again. I would never date someone who, when our love had corroded, could use his whiteness against me as a weapon. I knew that what he said was true – that any story he chose to tell would be believed. It would be believed because of our different bodies, and the different meanings that our bodies produce.[15]

And perhaps the most beautiful statement of Miller’s re-familiarisation with Jamaica, and a queer Jamaica at that, are his wonderful essays on the ‘Gully boys’. These boys, whose sexual and sex/gender identity choices cross every boundary, are frankly for ‘rent’ but they also are an example of a terrible beauty being born in changes in Jamaica and mimed in Miller’s sentences.

In Kingston, at night, the harbour is beautiful – almost as beautiful as the boys who gather around it, the boys who are still young and still have dreams as big and bright as the fireworks that light up the waterfront each New Year.

We can and often do choose not to see the boys:

… .And maybe, even tonight, though it isn’t New Year, if you pass by the harbour, you will not see them either, sitting as they do in the shadows, under the sweet almond trees – these boys talking about their big and bright dreams.[16]

But these big and bright hopes aside, Miller has exposed difficult truths about how the meanings of bodies are moulded and how these meanings emerge in even the closest interaction between white and black people.

These essays start and end with direct address to James Baldwin, a queer black male body known to Miller only as ‘a body of work, and I can write back to that’.[17] But that body of work is and continues to be predictive. Miller tells a story of becoming a professor in a US university where a white cleaning lady screams at his unaccustomed, to her, black body appearing in the corridors allotted to her duty and reports him to security men who demand his ID papers. He tells this story with considerable wit, only half withholding its underlying meaning and associated pain. It is painful because here again were, he explains to us – but not to them – historic ‘old Black codes being enforced’. It is the more painful that the circumstances retailed allowed that there be no room for explication of their effect on him and his body at the time: ‘no way to say any of this, James – to talk about the history that had become so painfully present, and how we all played our roles so brutally, so perfectly’.[18]

Again, In the address to Baldwin completing the book, the dead writer’s awesome ability to predict the longevity of these ‘old Black codes’ is invoked to collapse the history of Black Lives sacrificed to them, and enforcement of them in white spaces since Baldwin’s death. He shows us that this history, in a way known to Baldwin’s writing but not to Baldwin, now includes the events related to the death of George Floyd, to which no man ‘racialised as black’ can be indifferent. Well they can in fact! If people accept that the Black Lives Matter groups should not ‘vex themselves when is just a set of criminals that the police did kill’, then indifference may win.[19] That this sentence uses the grammar of Jamaican English speaks volumes.

There are multiple versions where a ‘terrible beauty is born’ in this book and I have missed out some favourites of my own like the re-readings of Carnival traditions and of family secrets. However, I couldn’t end without reverting to the prefatory poem, or should we say, ‘proem’. Let’s see it again:

Earlier I tried to show how I read this remarkable piece but Miller actually uses his discourse with Baldwin not only to laud Baldwin’s clarity in prose and set that up as his model but to mourn that James failed to see why poetry mattered in ways that meant James could have written it for himself, except for the failure in Jimmy’s Blues (not Baldwin’s fault since he chose not to publish it) ‘to pack enough into that most basic unit of poetry – the line’.

He goes on to explain why the ‘lyric line and what could be contained in it’ matters. The line is itself a recognition of the strengths and frailties of the body (Wordsworth, after all, would have understood that, and Langston Hughes, though Baldwin dismisses him, better than James Baldwin). Poets and their embodied poetic voice, after all, understand:

… how that line might break and how it might take its breath. … [and enable] … – poems in which the body was present and vulnerable, and that broke in the same soft places where lines break’.[20]

I find that unbearably and terribly beautiful, just as the lyric lines from our proem from this book that break into and over ‘white space’ are beautiful and terrible. They are moments of withholding the breath – they are the body of a poem. Another great queer poet – Andrew McMillan (though a white poet) – is good at these as an expression of ‘breaking’ of different sorts. Yet the wisdom is the same as in these lines of Lines Composed Above Tintern Abbey, where the breath and blood mean the body released as emotion, but from a privileged history in which poetry could mean restoration because it ruled and regulated the same white space as the outside world, and was not broken by what it withholds:

With that contentious note, but one full of love for poets who examine the break rather than the restoration in a fundamentally broken world, I’ll take my leave. Read these tremendous essays. I feel passionately about their urgency. Maybe you will too.

All the best as ever,

Steve

[1] Kei Miller (2021: 8)

[2] ibid: 121 & … 124 respectively.

[3] Ibid: 20

[4] Dionne Brand, cited, for the first time: ibid: xv

[5] Ibid: 132f.

[6] Ibid: 10

[7] Miller, K. (2013) ‘An Occasionally Dangerous thing Called Nuance’ in Writing down the Vision: Essays & Prophecies Leeds, Peepal Tree Press, 91-95.

[8] Miller, K. (2014: 24f.) England in a Pink Blouse in Barley, N. & Doherty, J. (eds.) Letters home Edinburgh, For Grid Iron Theatre & Edinburgh International Book Festival by Serpent’s Tail, 11 – 28.

[9] Miller, K. (2006: 126) ‘The Fear of Stones’ in Fear of Stones and other stories Oxford, Macmillan Education (in Macmillan Caribbean collection), 91 – 141.

[10] ibid: 136f.

[11] Miller (2021: Chapter 9).

[12] Ibid: 125

[13] ibid: 121 & … 124 respectively.

[14] Ibid: xiv

[15] Ibid: 67

[16] Ibid: 81. My italicized summary added between citations.

[17] Ibid: 1

[18] Ibid: 10

[19] Ibid: 201

[20] Ibid: 3. My italicized summary added between citations.

Reblogged this on Steve_Bamlett_blog.

LikeLike