‘…, I should acknowledge my own experiences, professional and personal, although in my own case these merge, since I never learned to make a distinction between the ‘academic’ and ‘personal’ approaches’.[1] : Unpacking Mary Ann Caws’ ‘case’ with reflections on her 2019 book Creative Gatherings: Meeting Places of Modernism London, Reaktion Books.

Mary Ann Caws is a singular phenomenon or, at least, this is how she represents ‘her own case’, which will emerge, not from the citation in my title alone but the content, manner of presentation of self and otherness and theory of knowledge and evidence throughout this book. The book is intended as a challenge to generic classification that aligns with Caws’ upbringing, social status, education and work (which includes that of writing academic and other texts in literature and visual art, including her specialism in Dada and the surreal (and other ‘modernisms’ in poetry and visual art), books on European cookery, biography and autobiography. The books dedication to Caws’ grandmother, Margaret Walthour Lippit, is no contingent whim – that relationship between generations of artistic making and social gathering are indeed the genetic spine of this book.

The story of Lippit makes an odd and rather lengthy intrusion, into an otherwise short review piece of another academic’s work on Paula Modersohn-Becker, that in fact carries a ‘germ’ of this book and the centrality in it of the Worpswede literary ‘colony’ (it is featured in chapter 9), if it can be called thus:

Another young female artist who visited the village was my grandmother Margaret Walthour Lippitt. She had attended the Académie Julian in Paris in 1898, a few years before Becker went there. (One day, Sargent came up behind her when she was sketching in the Louvre and remarked on her auburn hair: ‘So like a Titian.’ She was not displeased.) In 1904, she went with her husband to live in Bremen (he was in charge of the cotton exchange there) and over the next ten years made frequent trips to Worpswede. She was especially close to Modersohn and to Rilke, neither of whose names made much impression on me as a child. We had a copy of Modersohn-Becker’s Goose Girl on the stairs, and the deep greens and browns of the northern moors perfectly matched the depressing folk tales my mother had been told when she was growing up in Bremen, and passed on to her own children.[2]

Not having previously encountered Caws’ work, my heart lifted when I read the words cited in this blog’s title in her introduction. Here, I thought, is a mind after my own, which rather despises the pretended relationship in art history to outdated (in science at least) positivist language (writing theses that ‘prove’ a point has they had it on my Open University MA course) and notions of ‘objectivity’ in statements about art.

But the point in Caws’ does not turn out to be a matter of the ontology or epistemology of art but rather a way of smuggling in various personal and family stories as central to the writer’s evidence. In effect, it reminded me why there had been an attempt to wrest art history from the hands of privileged subjective commentators and establishing around it a sham-positivist framework. Not that there aren’t moments of personal intervention in relation to value system that touch on the political in the personal experience of marginalised people, although the author’s position on them can be difficult to tease out. I find this so as in her comment on her prevarication on whether or not the Black Mountain Community College was guilty of prevarication on issues of gay rights, in relation to the rector and pedagogic innovator, Robert Wunsch, who was also queer and policy on ‘racial integration’. As far as Caws is concerned, the matter is best explained in terms of the ‘turmoil and controversies’ that ‘happens in any community’, and uses one critic of the lack of support given to Wunsch during the time when the Black Mountain community keenly attacked him for ‘crimes against nature’ to reinforce this rather laissez-faire attitude to open and inclusive democratic values.[3]

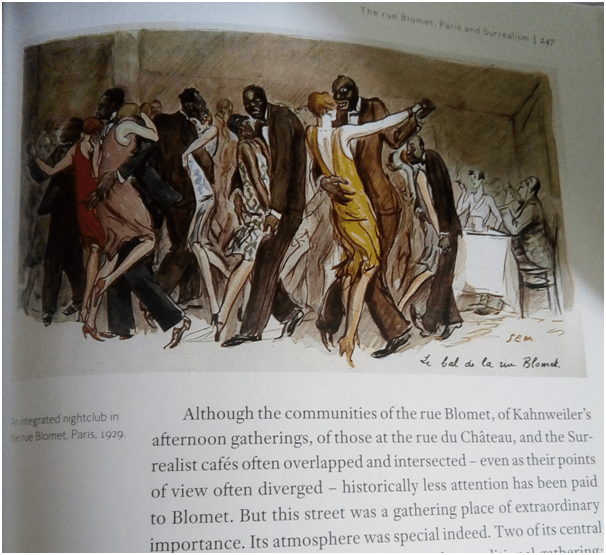

There is a caginess in Caws’ prose here that fails to commit to inclusive personal values rather than defence of the failure of some groups to really work with marginalised people on the edges of their proffered group experience. That is why I have chosen to honour him with the photograph above, not used by Caws. I was even more concerned with the representation of ‘racial’ integration, according to Caws’ stance on that within artistic gatherings in relation to her chapter on the group of surrealist artists circling around the studios of Joan Miró and André Masson in rue Blomet in Paris in Chapter 16. In this chapter she focuses towards the end on the Bal Nègre, which to Surrealists she argues ‘represented the unconventional Other, sought out for its power to shake up bourgeois mores’.[4] Even with allowance for historical change, this group attitude – which I do believe to be exactly that of the Surrealists – is hardly about inclusiveness and integration but rather exploitation of the ways black people are represented as marginal in racist societies. It is a moot point whether it isn’t an example of ‘bourgeois mores’ itself.

It may be unfair to expect much from Mary Ann Caws here but I think we have to be cautious in understanding exactly what she means by introducing the ‘personal’ into the realm of the ‘academic’, despite my wish to praise her for that formerly. For instance this chapter opens with an illustration in colour meant to represent a caption reading: ‘An integrated nightclub in the rue Blomet, Paris, 1929’.[5] I show that page below but also apologise to anyone from the black community who may chance to see it, for this not only ‘others’ black people but renders them as grotesques and sexual predators – a stereotype so close that of ‘bourgeois mores’. Yet there is no comment on this from Caws, who must have approved its inclusion.

These points are what make me draw back from the admiration I originally felt for Caws’ challenge to academic art history and long here for a little more objectivity or a subject-position that takes responsibility for the images it uses to represent the relationship between art and life/lives. However, that said, it seems important to chart some attractive qualities in this book, before again pursuing why it, as a text of our time, hovers so on the cusp of what is ‘personal’ and what is ‘academic’ in the history of art.

Of course one quality of such works is the kind of work they do in order to justify previously unexplored concepts as a means of reinterpreting the history of art. For Caws the central concept is the ‘gathering’ or ‘meeting place’ for artistic groups, although it extends to the more well-trod concept of the artistic colony. The introduction to this work attempts a synthesis based on these ideas by play with concepts of the central role of tables ‘around which given groups might assemble’.[6] This allows Caws to focus on dining tables as well as the tables of a bar and to invent phrases to prosecute her argument such as ‘tabling places’. Short of that she imagines the exchanges between the members of any gathering as ‘talk around the table’ as a symbol of ‘the life of the arts: the turning towards and working with other creative beings’.[7] However, my impression of this attempt is that it too often falls flat and is neither utilised in many of the chapters – each an instance of a place at which gathering occurs at a moment of history or even over longer periods – nor even referenced. Sometimes it allows Caws to digress into her personal interest as a gourmand and cookbook writer, as for instance, when she tells ‘amusing’ stories of how, while feasting on a ‘beautiful plateau de fruits mer’, on the way to Pont-Aven, the Breton gathering place of Paul Gauguin and Émile Bernard, among other groupings at different periods of modern art, she ‘upset’ her plate of seafood, and provides a photograph of such a plate (dated July 2016) for those who are unsure of how to read menus in French.[8] For me this was a sad moment of realisation that the ‘personal’ for Caws wasn’t really much more than a way of collecting together her own take on what makes privileged Americans feel they have a foothold in Continental Europe.

This has a benefit in that it shadows the nuanced European character donned by Henry James and John Singer Sargent in Florence and Fiesole (Chapter 2) and Venice (Chapter 3). And above all, it allows Caws to continually resurrect her especial access to the memories of the European exploits of her grandmother, Margaret Walthour Lippit. For we not only hear of her proximity to the writers and painters of Worpswede in Germany but of her training in the Académie Julian in Paris with a less celebrated member of the staff, the Paris salon painter, Alexandre Cabanel, after dealing with much more substantial Russian painter Marie Bashkirtseff and before launching into stories of more celebrated American female artist, Cecilia Beaux. Caws obviously likes Cecilia who, in her modesty is ‘the kind of creator we admire’.[9] In contrast Bashkirtseff’s view that she was neglected because ‘of the bourgeois inability to understand her artistic sentiments’ is given a thumbs down, as, perhaps ‘not someone you would have liked, given her essential self-sureness’.[10] I find these personalized assessments of female character quite off-putting, but is this a remnant of old Adam sexism in me (or old Eve sexism in her)? This indeed reminds me of the gentle wash of conversational gossip about art and artists from the bourgeois dinner ‘table’ but it does not enhance my view of why ‘gathering’ is an important concept for artists. Of course other parts do, most notably the chapter on Charleston (Chapter 17), where conversation around a table prompted art directly engaging with such tables in the novels of Virginia Woolf and paintings by Vanessa Bell and Duncan Grant.

In my view the most successful concept used to illuminate at least two of the chapters , little or nothing to do with ‘gatherings’, it is the use of settings in Parisian ‘passage’, a topographical picture which Caws elevates into her best critical insights into why ‘passage’ is an important concept for Surrealists who gathered in the passage de’lOpéra. Caws writes in Chapter 15 on Surrealist Cafés about this shift of ‘focus’ to the passage thus;

Just as important as the gathering of the group, however it was constituted, is the location of the passage – that to-be-traversed place, the diametrical opposite of the staid and the stable. The idea of the passage links, in the architectural construction of glass covering the sidewalks of shops, leading from one sidewalk to another, , natural daylight to artificial lighting, the outside to the inside: …. So the passage is multiform like the Dada and Surrealist text.[11]

Just a step from this we get the application of Jean Rousset’s description of Baroque art and architecture: “a style of metamorphosis ….an unstable equilibrium due to the multiplicity of perspectives, of organizing centers, and of mental and imaginative registers”.[12]

There is no better or more relevant moment in the book than this but, unfortunately, also no analysis of particular works (text or image) that makes use of what is gained here in critical insight, although the quality of the reproductions of appropriate works of art for this purpose is astounding and beautiful. The commentary on them prefers the retail of the second-hand, of gossip in the background of the work’s creation to critical commentary and analysis. This is quite usual in the history of art – I remember a critical comment from the marker of one of my submitted MA scripts that I should not use my own analysis, but rather more the views of ‘experts’ and contemporaries – but it should be remembered that Caws professes expertise in literary text as well.

Of course the quality of the photography and the new knowledge about moments of history of which I was before quite ignorant makes this a book I want to keep on my bookshelves, but it further homes my personal critique of that bricolage discipline, or rather patchwork, we call the history of art, where the work of a multidisciplinary scholar of great personal insight and skill with the use of evidence like Simon Schama might rub shoulders with something so much less precise and yet so much more dryasdust as anything Thomas Carlyle ever imagined as the stuff of art history.

Of the moments of joyous learning I would include the gorgeous Chapter 1 on L’École de Barbizon, not least because of the light shed on the austere image I had of painters like Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot, Daubigny, Theodore Rousseau and Jean-Francois Millet. In writing doggerel French verse for the Auberge Ganne which housed them they played with puns on Barbizon, that, to find a suitable rhyme and assonance, played delightfully with comparisons of their bearded masculinities with the look of bisons – get it ‘barbes’ and ‘bisons’.

Ces peintres de Barbizon

Ont des barbes de bisons.[13]

Almost in the manner of a group in-joke, soon the ‘bisons’ get totally released from their function of rhyme and assonance and the group start using it as a verbal icon of their identity as a group, who ‘Peignent commes des bisons’ (‘Paint like bisons’ – What?). Or even more amusingly of nights at the in n amongst these obviously jolly men:

Certain vin de Barbizon

Qui f’rait valser les bisons

Caws’ translation

[A certain wine of Barbizon

That would make bisons waltz]

This is a delightful book to own but does it really serve a purpose that is even remotely about learning per se. Rather it reminds us that the traditions of knowledge are always owned, when they are reserved to institutions inclusive in their intake and exclusive in their sharing of knowledge, and that applies even to such institutions as call themselves ‘open’. What drives me to write this waspish reflection is hope that there are alternatives and my next blog is on one such: Russell Tovey and Robert Diament’s talkART published this year. But I still need to start that blog, which grows out of the very real sense of open and yet diverse community I sense behind those lovely lively fellows.

All the best

Steve

[1] Mary Ann Caws (2019: 24)

[2] Caws, M.A. in (2013) ‘The Artist as Fruit’ in The London Literary Review (online).Vol. 15 No. 35 (8 Aug. 2013) Available inMary Ann Caws · The Artist as Fruit: Paula Modersohn-Becker · LRB 8 August 2013

[3] Caws, M.A. (2019: 285)

[4] Ibid: 260

[5] Ibid: 247

[6] Ibid: 15

[7] Ibid: 8

[8] Ibid 121f.

[9] Ibid: 87

[10] Ibid: 77f.

[11] Ibid: 238

[12] Cited ibid: 238

[13] Cited ibid: 36. Translated by Caws thus: These painters of Barbizon / Have bison-like beards.’ (ibid: 37)

Steve, you’ve put so much work into this review, I hope you’re trying to get it published somewhere?

Adios,

Alan

LikeLiked by 1 person