‘He seemed to want to drive home the validity of his passion’.[1] Ernest Frost’s (1953) A Short Lease: A Novel London, John Lehmann: Lost Voices and the Queer Novel

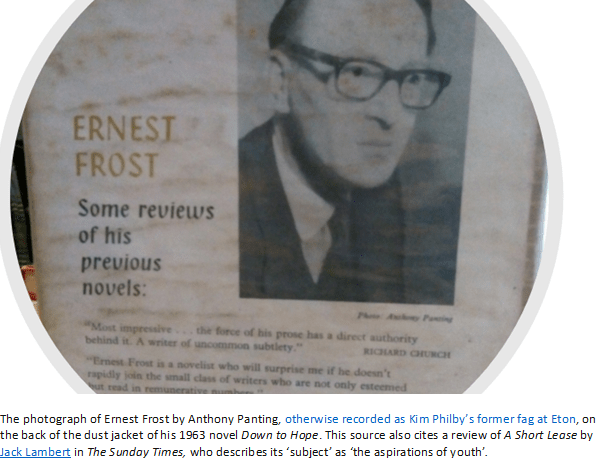

Jack Lambert in a contemporary review of the novel in The Sunday Times confidently describes the ‘subject’ of A Short Lease as ‘the aspirations of youth’. And youth was also very much on Frost’s mind in the novel that, after a ten-year period of silence as a novelist that followed The Visitants in 1955, Down to Hope. That later novel starts by ‘youthful aspiration’ being put firmly in its place by those with age and authority, whether they be fathers or headmasters in academic gowns, who attempt to shape youthful subjectivities and choices, even from that novel’s opening line,: “When I was your age …..”.[2] It even uses this theme in its epigram from George Barker’s poem, Allegory of the Adolescent and the Adult.[3]

It’s worth emphasising this decisive shift to the perspective on the young middle class white man, since Frost’s first two novels reflect so much on earlier life choices made by older men who from the start of the novel had aged to outlive the consequences those choices brought to them. The Dark Peninsula and The Lighted Cities are very much preoccupied by older unmarried white men, whose status and class has become less certain as the qualities that once made them notable have faded with time, exhaustion or, quite as commonly, the appearance of being no longer valid members of the human race, especially in their emotional and sexual lives. It’s a theme that never leaves Frost’s repertoire and is explored in his final novel (the aptly titled It’s Late By My Watch). However, the older men of the first two novels are markedly different say from the charming Henry Taggart of The Visitants, who had ‘met everybody in his time’.[4] By implication, now in his sixties (considered ‘old’ in 1955), it is no longer Henry’s time, and his art has dated with his energies. On the other hand, the central figure of A Short Lease, young Harry Cull, feels that the time ought to, even where it obviously does not, belong to him and his effeminate novelist chum, Peter Milton, rather than to the older generation of his now dead father (Roland), whom everybody but his son loves. But more of this later.

Martin Dines has characterised the 1950s as an ambivalent time with regard to the ‘homosexual novel’.[5] He has described the plethora of novels about sensitive middle-class men criminalised by anti-gay legislation (for most of us contemporaries Dirk Bogarde played this role in its archetypal form in the 1961 film Victim). More significantly, these ‘gentle’ men are thought to be victimised by decidedly lumpenproletariat elements conceived to be ever hungry to deprive them of the fruits of their exclusive education, status and treasured individual privacy.[6] Dines characterises the overt intent of those novels as firmly to support a resolution, to come in the form of an Act in 1967, which decriminalised those able to make individual or ‘private’ choices about the objects of their embodied desire, whilst exposing those without ‘private’ resources to continued oppression.

By situating their homosexual protagonists firmly within middle-class domesticity, these novels reproduce a principal argument of liberal reformers: that the right to conduct sexual relations should be extended to homosexual men, so long as such affairs take place in private. In so doing, the 1950s homosexual novel implicitly sanctioned the homophobic interventions of the law and the media which mainly targeted the public urban spaces that men with fewer material resources relied upon to sustain affective and erotic relationships with other men.[7]

Ernest Frost truly sits in an entirely bourgeois conception of what relationships between men might mean and both celebrates their potential intimacy and expresses distaste for the socio-political mechanisms that block its frank expression. Frost’s intention appears to me an extension of how Dines describes the implicit agenda of Iris Murdoch’s The Bell: ‘critical of the influence of the popular newspapers’, and showing, ‘that homosexual encounters need not be merely shameful and damaging’.[8] Yet in the case of both Murdoch and Frost, these novelists are mainly ambitions in their novels to establish ethical and aesthetic goals that over-ride attempts merely to create positive imagery for a particular social and personal identity like ‘the homosexual’. These novelist insist that they do not only have responsibility to creating images conducive to the positive self-esteem of a group of the currently outcast, at least in any simple sense, but also for diversifying the sources of pride beyond heteronormative, and even homonormative, models to engender ‘pride’ in relationships considered, for political reasons, to be socially transgressive. It always upsets me as a reader that queer diversity remains the road less travelled in histories of, and publishing ventures for, the queer arts. Hence in my title I point to a theme partially delivered in my citation from A Short Lease in which the focus is not the validity of an identity but of the validity of a relationship and its interpersonal and intrapersonal expression – ranging from short-term desire to longer-term love: ‘He seemed to want to drive home the validity of his passion’.[9] Of course identity matters but Frost is preoccupied with why some kinds of loving and creative expression are considered transgressive and the causes of the alienation of these kinds of human expression from common human experience.

For Frost, both art (painting, poetry, music) and queer sexuality create marginalised figures when they cause their disciples to tread a different path to that of convention. Anthony Slide has summarised this brilliantly by pointing out that, in The Dark Peninsula, there are multiple references to the social outcast. Yet when the shadowy figure A (dead long before the novel opens), who was once beloved by men with varying need for that love including Mullholland, speaks about, ’the outlaw, the terrible leper in a London square, the misfit, the beggar in Battersea Park (p. 224)’, he is talking of the poet not of the queer male. Slide says: ‘The analogy between the poet as the outcast and the gay man as outcast is very obvious; it is there without being written on the page’.[10]

Anthony Slide’s summary of this novel (only 3 printed pages) is necessarily short of detailed evidence for his assertions but they seem to me extremely well judged and perceptive. For instance, consider this useful summary of the key military men in the main character set of the novel. I couldn’t improve on it.

A group of British soldiers are occupying the region [in Southern Italy], and the first two to be introduced are Lieutenant “Mully” Mullholland and Private Arnold Thompson, who enjoy an uneasy friendship. Something is obviously strange here, when the latter look at Mullholland and wants “to run his fingers over the jaw, to feel the light stubble of beard which glinted in the daylight” (p. 12). The reality is that Mulholland does not care for Thompson, grows intensely to dislike him, and that both men are heterosexual. The gay member of the group is their commanding officer, Colonel Judd.[11]

The inference for me is that the passion that bonds men has no clear norms in its motivation and practice except those imposed on it by alien rule systems. The issue is not ‘the homosexual’ or ‘the gay member’ of any society alone but the queerness of real rather than ideological male to male feelings and their expression in speech and/or the body. Slide makes this point clear later:

The Dark Peninsula is a novel in which homosexuality is not once mentioned by name, but one in which it is all-pervasive, both dangerous and desirous. In a unique sense here, it holds the power of life and death. The love of Judd for Thompson is a beautiful thing. When the colonel rakes Thompson’s hand, “The body, supple and necessary, lay on his longing like a rose” (p.130). …[more examples] … It is a powerful narrative, intense poetry, a drama between the two that transcends the mere physical.[12]

My only reservation to Slide’s characterisation of the novel is that I believe that what is all-pervasive in it is NOT ‘homosexuality’, which can then be described as ‘dangerous and desirous’. What is all-pervasive is desire itself that manifests across distinct communities, even all-male one like that constituting an occupying army, and which may bear different meaning in different relationships of couple or groups regardless of the gender mix of those groups. It is desire that is experienced as ‘dangerous’. Hence, I think that we should not look beyond the ‘obviously strange’ feelings that might be evoked in a reader since it those queered (and thus ‘strange’) feelings that mark the queerness of behaviours that transgress labels such as that we name ‘heterosexual’. We know, for instance, that Frost presented his book to his wife, Phyllis, and that its personal reference was known to her.[13] It is with that sense of queerness beyond norms that all of Frost’s novels actually work (especially with regard to age differences between lovers) rather than merely differences in social identity. There is after all something distinctly like embodied desire set free in the very idea of a ‘dark peninsula’ that Frost uses to name the effect of Italy on imprisoned British minds that we see too in his poem Italy, 1944.[14]

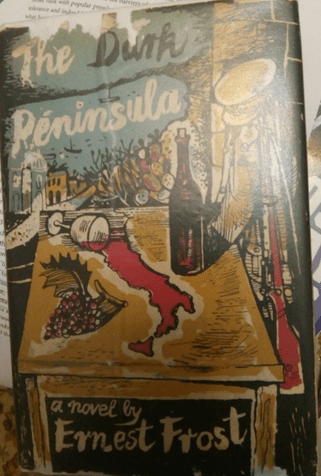

John Minton pictured Italy on the 1949 dust jacket of the novel, with what prompts from Frost we will never know, as a wine-stain on a Mediterranean seaside table. The stain proceeds from a glass upset on it and its red is reflected faintly in the bunch of grapes cast aside, presumably by the absent soldier, and in his erect gun, which rests against his discarded outer clothing hanging against the nearby wall. The disruptive power of passion spent seems to me the referent here that is perhaps symbolised in all of the cover’s symbols coloured in that same red: the gun, the bottle of red wine, the wine stain itself, and the discarded grapes lying across the cork screw that had been used to open the re-corked bottle. In the Mediterranean context – the bay dominating the symbols of dryness and control (that church cupola for instance) on land – is already a very Dionysian symbol of passion disrupting the order of things. It is embraced by a circumambient black darkness, that is recalled too in the mix of the wine bottle, in which a man has laid down his arms and rested himself for the night in ‘exhausted sleeping’.

The sexual content of A Short Lease is equally estranged from the norms of the 1950s novel but in this novel there are many potential references to ‘homosexuality’, often in forms that are meant to show masculine distaste to the subject (such as ‘Homos’, ‘queers’, ‘pansies’, ‘sissies’ and ‘catamite’).[15] There is even, proximate to a playful use of the term ‘Camp’ and Hellenic or ‘Grecian’ fantasies harboured by the linen laundry owner, Tom Aston (once in love with Harry’s father), use of the word ‘gay’ to describe Harry Cull which I cannot be convinced does not show the word-use in preparation for transition. Recounting this episode of having ‘a kind haggard man fussing over him’, [16] to his friend, Peter Milton, Peter says:

… “You’re not getting mixed up with homos are you!”

“No,” said Harry vaguely, but he noticed Peter’s quickening interest, the slightly feverish way in which he said the word “Homos”.

“Well, you’re not exactly Grecian,” Peter sneered gently.[17]

This ‘topic is always spoken about in context where ambivalence is also always evoked. Hence a ‘quickening interest’ might be expected from readers too, given the strangeness with which even characters in the novel react to it. When Harry thinks about people he loves (and who might, in his paranoid mind-set, also ‘betray’ him), he continually compares Judith Aston, the older sexually experienced woman married to Tom and Peter Milton, a virginal young male and aspirant poetic novelist, of the same age as himself. Once Judith shows bitterness to him, for instance, he wishes, ‘he were back in Peter’s tower which was so insulated against the world’.[18] Harry’s wise Aunt Margaret even refers to Harry’s absence from Peter as a ‘lover’s tiff’. This is a joke of course but Margaret takes it into the same realms of interested and slightly ambiguous disapproval as had Peter previously with an emphasis on Harry’s duty to develop into heteronormativity:

Her eyes twinkled but it was the twinkle of a scalpel, some instrument to dig out Harry’s secret affection and show it, wriggling, embarrassingly naked, on the steel tip. “ … get yourself a nice girl. I sometimes think your friendship with Peter is just a little unhealthy. Like a couple of girls, you are.”

“We’re not, “ said Harry stiffly. “Our relationship is utterly masculine.”

“But that’s the trouble!” Aunt Margaret cried. …[19]

Likewise Harry’s sexualised jealousy of Peter’s fascination for a more socially successful artistic rival young male, Vivian Maxwell, extends to accusing Maxwell of being a potential rapist, as he spies both men walking with ‘Many lovers’ into the woods:

How intent they were to each other! How effeminate their intensity, their affected voices in the semi-darkness!

…

What the devil are they talking about, Harry thought. Why the hell don’t they have done with the jabber and get down to the rape.[20]

The ‘feverish interest’ that animates the choice of diction here is surely Harry’s own. It recalls how Harry ‘blushed’ in helping the drunken Peter vomit by pushing his fingers down the latter’s throat (after the latter’s boozy first meeting with Maxwell) because it seemed, ‘like an enormous intimacy’: ‘It was like going to bed with Peter’.[21] These games with gender and sex are widespread and often played for open and rather unshockable comedy. The novel has it own alpha male ‘Colossus’: ‘manly if nothing else’ thinks the woman who fancies him.[22] His sexual allure is such that it has its own name (‘Bensexuality’); he is a young surgeon, Ben of course by name, who is already, we are to discover by the novel’s end (had we not guessed it already), having an illicit affair with Judith Aston.[23] Ben ‘hated sissiness’.[24] On the other hand he has no problem in playing honestly suggestive word games with Peter Milton about who is sleeping in which bed and with whom: ‘“Bugger off, Milton,” Ben whispered. “I’m locking up. No party tonight, amico. We’re all going to our separate beds”.[25] There is something of the ‘cock-tease’ about Ben.

Of course, the real conflict in Harry’s life is that with his father; a conflict which Tom Aston’s obvious passion for Roland Cull only emphasises, since Tom seems intent on seeing Roland as in a sense reborn in Harry just as other family and political admirers of the former continually do. There is a hint of the dead and drowned fathers of Shakespeare’s The Tempest and of failed models of transmittable masculine authority about the figure of Roland Cull.[26]

Full fathom five thy father lies;

Of his bones are coral made;

Those are pearls that were his eyes:

Nothing of him that doth fade,

But doth suffer a sea-change

Into something rich and strange.

People see the likeness of Roland in Harry in ways that make Harry feel even more ambivalence about his father as a model for his own life. The examples of such people range from his Gran who runs a domestic laundry business, cheaper than Aston’s Rivermead Laundry, and the local council and police who act towards Harry as if he reflected Roland’s glory. This is especially poignant when the Local Council Education Committee dedicate a new school in his name. Tom sits on this committee and his use of influence here seems an illicit means of demonstrating a love for Roland that, otherwise, ‘dare not speak its name’.[27]. Henry Milton too, Peter’s father, says Harry is ‘like’ Roland and this is not the only time that Harry feels that the drowned man is being ‘resurrected’.[28]

It was as though the world had conspired, this Maytime, to resurrect Roland everywhere. Never would Roland be left under the weedy water at Taggart’s Island, but he must be dragged out everywhere, at any time, to give the present shape, or purpose, …[29]

Harry believes himself in love with Judith Aston (Tom’s wife) whose actual sexual preference is (but unspoken openly – though astute readers will guess it – till late in the novel) is for Ben. When Judith asks Harry if Roland was, ‘like you to look at’, Harry claims that ‘he’d rather be dead than be like him’.[30] He says that he feels Roland ‘wanted universal loving kindness on easy terms’, whilst not seeing ‘how those easy terms wrecked other people’s lives, the people hidden away …’.[31] This is not just pique against Roland’s liberal left politics, that embraced ‘deserving cases’, whilst being, in his son’s eyes, unaware of the harm his supposed generosity did to his wife, Harry’s mother. It is also a feeling of loss that Harry constantly affirms by his denial of the fact that Roland, ‘did nothing to me or for me’.[32] Harry’s difficulty with the Dad who will not stay drowned is that he himself is drowning in his inflexibility of feeling that force unnecessarily extremely binary choices upon him: being ‘still immersed in the problem of his father’s character’ (my italics).[33]

For Harry needs to realise that he is very like his father, in need too of ‘approbation’. When he does not get it, without working for it, Harry is continually ‘questioning friendship’, oversimplifying characters like Vivian Maxwell (or his father) in the most stereotypical ways and ‘full of resentments’, as Peter near the end of the novel rightly accuses him.[34] He is like ’a mere boy’ indulging ‘fine romantic feelings’, Judith adds, before the novel concludes.[35] Soon after Peter’s accusations Harry will consider whether, ‘he is all wrong about his father’ and see him ‘as a better man’.[36] It is Judith who finally forces Harry to accept the ‘fallibility’ of all human endeavour and to realise that ‘positive actions’ are not conditional on perfection of character but on genuine feeling in relationship to others regardless of labels. It is her who forces Harry to begin to see the importance of impetuous volatility, even at cost to others. He will hear, in her own words, that Judith can value Roland Cull for giving her passionate husband someone to love that was not herself since she could not be that person. It is this fact that allows her to enforce the learning that Harry should value what Roland actually was to Harry’s mother and not what Harry thought Roland ought to have been:

“You can’t run love on cylinders filled with nothing but loving kindness; there has to be something more volatile. … You were always attacking your father for his feelings of loving kindness, but believe me he backed them up with positive actions. He cleared those slums in Nixon Street. He supported negro G.I.s. He gave my husband a happiness which, through my own fault, I was unable to give. …”.[37]

In the end, we have to return to this being a novel of relationships. Of course, there was nothing new here, even when Frost was writing, of seeing the novel as modelling relationships that skew, or in terms I prefer, queer the current norm. This is the undercurrent of E.M. Forster’s project as a novelist, although his concern was too often a pure reflection of the queerness of Bloomsbury and King’s College Cambridge. Indeed the failed novelist in this novel, Peter Milton, too learns from being introduced to Fats Waller’ ‘Dry Bones’, and by extension Vivian Maxwell, what his literary theme ought to be. It is the same theme, with a provincial and middle-class setting, as that exampled by a great queer forebear, Edwin Morgan Forster. Speaking of a drunken night in the Wellington public house we hear about near the beginning of the novel, Peter near the novel’s end says:

“… Heartiest congratters, cull … You unmasked me, Harry. You slapped me down in the world, plonk, and got me drunk. (…) … And I sang that little song about bones.” …

“That’s quite a leit-motif in our lives,” said Harry crossly. “I hear it wherever I go. Well, maybe you’re right.”

“It means, only connect,” said Peter gaily. It’s common sense, boy. Only connect and you shall be, an integrated personality.” / … .[38]

Forster’s phrase (‘Only connect’) was used as the epigram of his novel Howard’s End, where queer marriages of ways of relating to others are made and broken that cross different kinds of boundaries. The phrase is amplified in that novel in ways that humanist thinkers still value. But Forster’s liberal humanism does not give us the only way of reading Forster’s radical look at the nature of relationship. In various ways, licit or illicit, it nearly always asks us to validate passion that lies well outside norms – whether of class, gender, race or even orientation, as in Forster’s 1907 novel, The Longest Journey. The case of Maurice (1913-14) is legendary but the novel was never published in the novelist’s lifetime, though it is likely John Lehmann knew of it (he was Frost’s publisher) given his close connection to Bloomsbury.

I can at this point in my argument easily return to the cited quotation in my title: ‘He seemed to want to drive home the validity of his passion’.[39].Tom Aston here is speaking of his love for Harry’s father, from whom he sees Harry as a descending visitant.[40] Indeed Harry is thinking at the time of Byron’s well-known poem about a descending Assyrian. He sees the value of Harry’s art later as the vindication in itself of the mission of Roland Cull, sayig:

“Roland taught me the value of feeling. … teach somebody about the way to feel, to break a lance for the heart instead of sticking a pin into the mind …” .[41]

If this is pure Forster, it is also about validating the feelings above cognitive structures, and particularly inherited social-cognitive structures. It is with that sense that passion validates ‘queer’ alliances (beyond social norms) that all of Frost’s novels actually work with (especially with regard to age differences between lovers) rather than differences in social identity. Of course the exact nature of the relationship between Roland and Tom is never specified. Why? One reason is that labelling it is a version of the sticking ‘a pin in the mind’ rather than valuing feeling. But valuing feeling means validating transgressive connections also. Harry was always wrong to set up people like Judith and Peter as alternatives to each other as choices of love-object or choice of gender attraction. You just need to validate the passion and be sure it’s not faked.

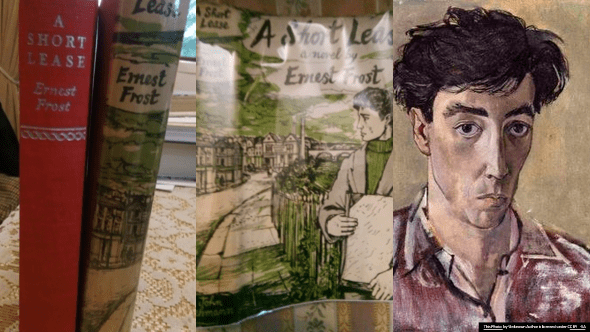

And, for Tom and Judith this aim is complementary to Harry becoming a true artist. “Nothing must come between you and your painting. Nothing”, says Judith emphatically (the italics here are Frost’s). And I am certain that, together with the understanding that a true artist is an outcast which I have already argued to be central to Frost earlier in this blog, this is why John Minton gave such personal attention to the dust jacket he designed for this novel for John Lehmann. Martin Salisbury, the expert on Minton’s book illustration work, says that there, ‘is a hint of self-portrait in his depiction of Harry Cull’.[42] Minton’s dustjacket selects two moments from the novel and combines them in a way that reflects Frost’s theme of a young man, aspirant but also alienated and outcast from the social world. The figure of Harry looks to me very near to a representation of Minton’s distinct facial features. It appears to reference a point in the novel where Harry carries a whole sheaf of his paintings in a portfolio and,to Judith, ‘seemed lonely and a bit aggressive’.[43] Unlike Ben, she thinks who is ‘manly’, he appears a type of the modern painter as moulded by German Expressionism (at various points his work is described as like that of Kokoschka[44]): ‘Painters nowadays, all subjective, tended to see people in aspects of their own neuroticism. …, they meddled with feeling’.[45]

For Minton, the portfolio represents the future of a graphic artist in making and he represents Harry (and/or himself) as pulling that portfolio into his body, protecting and perhaps caressing it. Harry’s eyes are downcast, as she might have appeared to Judith and perhaps look with distaste at the scene, central to which is Aston’s industrially conceived, Rivermead Laundry.

The scenic background recalls the very painting of Harry’s that is praised by Tom Aston and which, to the latter, expresses not only a fine landscape but the feeling of belonging in Duttonbrook he associates with the dead Roland Cull (his once beloved) and Harry’s father. This painting prompts Tom’s intention later to provide Harry Cull practical help in his career, perhaps even an entry to an Italian university scholarship. The icons of Roland’s love for Duttonbrook are, Tom says, in describing Harry’s picture in Chapter 6, the ‘wretched river’ and ‘Duttonbrook Bridge’ both of which are the background for Harry’s figure rather than the more commercial and industrial signs of this provincial town. And both promote a ‘heroic peroration’ from Tom about Roland’s sense of being bound to the pictured place that characteristically Harry, though here perhaps at his most neurotic, thinks of as being ‘caught in a dishonest ecstasy’ from which he ‘wanted to be free’.[46] The choice of figure and background then by Minton appears to reflect Frost’s view of the destiny of the artist, a destiny that will ring through every novel of Frost, whether the artist’s medium (be it graphic, music, words, or, as in the poet, an amalgam of those expressive types). But, we need to see how pertinent is this destiny to the validation of choices made by passion rather than convention, or even reason.

Now this individualistic way of posing the queer dilemma is both limited and bourgeois in its formulations in these novels, as in Iris Murdoch’s contemporary works. But choosing to validate the relational aspects of love is a means of advocating a queer estrangement from norms that doesn’t expressed when we concentrate on queerness as an identity, as in the mainstream history of LGBTQ+ liberation. The path that promotes above all other goals a social identity has left open truly reactionary responses to identity based solidly in a conventional pre-modern conception of biology. J.K. Rowling has represented that sorry tendency best in recent history.

The pride of Tom Aston is one that validates loving across the boundaries of difference and is truly queer, without needing to specify any fixed sexual orientations or identities. Is that enough for a truly responsive queer theory? I think the answer must be: ‘No!’ In Frost’s novel, the importance of the brutal effects of political power to deny or appropriate the resources of the marginalised and hold them down under the gloved hands of those who maintain the status quo is under-estimated. The resolutions in his novels (and Murdoch’s) are too symbolic and literary as well as being in the hands of individuals rather than socially inclusive groups. The concentration in A Short Lease and The Visitants on the individual is I think even greater than in The Lighted Cities and The Dark Peninsula. But colluding in the disappearance of voices like his (probably now irrecoverable but one tries) and Iris Murdoch (which is still redeemable) would be a detriment to literary history contributing to a richer queer theoretical approach to the arts.

Steve

____________________________________________________________________________

Appendix 1: Steve’s Notes.

κιννελλο (p. 24 etc.) is Greek for cinnamon.

A Project for a Self-Published Book on Ernest Frost

Chapter 1: Frost and the ‘Hominterm’: the role of John Lehmann as a publisher and

Chapter 2: The Dark Peninsula, Male Sexualities, Power and Male groupings (the occupying Army in Italy_

Chapter 3: The Lighted Cities: Art, Age and Aging in the Urban Modern.

Chapter 4: A Short Lease – based on this blog.

Chapter 5: The Visitants: The apotheosis of a term.

Chapter 6: Down to Hope: Youth breaking in and through an age of conventions

Chapter 7: It’s Late By My Watch: ‘a gay goodnight and briefly turn away’ (Yeats epigram).

Chapter 8: Being Out of Print and Queer Theory – Intervening in Literary History.

Appendix 2: Allegory of the Adolescent and the Adult George Barker

It was when weather was Arabian I went

Over the downs to Alton where winds were wounded

With flowers and swathed me with aroma, I walked

Like Saint Christopher Columbus through a sea’s welter

Of gaudy ways looking for a wonder.

Who was I, who knows, no one when I started,

No more than the youth who takes longish strides,

Gay with a girl and obstreperous with strangers,

Fond of some songs, not unusually stupid,

I ascend hills anticipating the strange.

Looking for a wonder I went on a Monday,

Meandering over the Alton down and moor;

When was it I went, an hour a year or more,

That Monday back, I cannot remember.

I only remember I went in a gay mood.

Hollyhock here and rock and rose there were,

I wound among them knowing they were no wonder;

And the bird with a worm and the fox in a wood

Went flying and flurrying in front, but I was

Wanting a worse wonder, a rarer one.

So I went on expecting miraculous catastrophe.

What is it, I whispered, shall I capture a creature

A woman for a wife, or find myself a king,

Sleep and awake to find Sleep is my kingdom?

How shall I know my marvel when it comes?

Then after long striding and striving I was where

I had so long longed to be, in the world’s wind,

At the hill’s top, with no more ground to wander

Excepting downward, and I had found no wonder.

Found only the sorrow that I had missed my marvel.

Then I remembered, was it the bird or worm,

The hollyhock, the flower or the strong rock,

Was it the mere dream of the man and woman

Made me a marvel? It was not. It was

When on the hilltop I stood in the world’s wind.

The world is my wonder, where the wind

Wanders like wind, and where the rock is

Rock. And man and woman flesh on a dream.

I look from my hill with the woods behind,

And Time, a sea’s chaos, below.

[1] Frost (1953: 96).

[2] Ernest Frost (1963: 7) Down to Hope: a novel London, Hodder & Stoughton.

[3] This is available I was surprised to find online at: https://www.babelmatrix.org/works/en/Barker,_George-1913/Allegory_of_the_Adolescent_and_the_Adult : see Appendix 1.

[4] Ernest Frost (1955: 8) The Visitants London, Andre Deutsch Limited.

[5] Martin Dines (2019) Chapter 4. ‘Is it a queer book?’: Re-reading the 1950s Homosexual Novel’ in Nick Bentley, Alice Ferrebe and Nick Hubble (eds.) [2019] The 1950s: A Decade of Modern British Fiction London, Bloomsbury Academic. Chapter 4. 111-140. Available at:https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/the-1950s-a-decade-of-modern-british-fiction/ch4-is-it-a-queer-book-re-reading-the-1950s-homosexual-novel

[6] For a variation on this theme see my blog on ‘The Heart in Exile’ by Rodney Garland (1953) available at: https://stevebamlett.home.blog/2021/01/16/its-not-a-good-thing-ron-to-be-queer-after-a-time-youll-find-the-right-girl-but-you-must-look-you-are-a-normal-person-who-has-been-infected-bei/

[7] ibid: 113.

[8] ibid: 118.

[9] Frost (1953: 96).

[10] Anthony Slide (2011: 92) ‘Ernest Frost: The Dark Peninsula’ in Slide, A. [2011] Lost Gay Novels: Reference Guide to Fifty Works from the First Half of the Twentieth Century New York & London. Routledge. pp. 91-93.

[11] ibid: 91

[12] ibid: 92f.

[13] “To Phyllis Frost, in love and gratitude from her husband Ernest 24/9/49” See Bonhams sale of first editions available at: https://www.bonhams.com/auctions/17160/lot/189/?category=list (accessed 25/02/2021)

[14] The veins of water

in this dark peninsula

…

The foliate cities

tread on fans of mimosa

and thrust their organs

through the upward playing

of water and sunlight. Over

their love and their exhausted sleeping

the far-off orchestra

in the mind hints of liberty.

From Italy, 1944 in Ernest Frost (1974: 7) Postcards from a Sad Holiday Nottingham, Byron Press Pamphlet Series 7, pp. 7f.

[15] Frost (1953: 39, 87, 111, 117, 200) respectively for examples of these terms in use.

[16] ibid: 26

[17] ibid: 39

[18] ibid: 168.

[19] ibid: 122

[20] ibid: 111

[21] ibid: 54

[22] ibid: 150, 115 respectively.

[23] ibid: 142

[24] ibid: 84

[25] ibid: 262

[26] Compare Magdalena Cieślak (2017) ‘Authority in Crisis? The Dynamic of the Relationship Between Prospero and Miranda in Appropriations of The Tempest’ in Text Matters 7,7 DOI: 10.1515/texmat-2017-0009 Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/320845654_Authority_in_Crisis_The_Dynamic_of_the_Relationship_Between_Prospero_and_Miranda_in_Appropriations_of_The_Tempest

[27] From Lord Alfred Douglas’ The Two Loves and associated, of course, with Oscar Wilde. See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_love_that_dare_not_speak_its_name.

[28] See Frost (1953: 14, 79).

[29] ibid: 109

[30] Ibid: 162

[31] ibid: 162

[32] ibid: 161

[33] ibid: 162

[34] ibid: 206f.

[35] ibid: 263

[36] ibid: 219

[37] ibid: 263

[38] ibid: 224 Frost’s italics

[39] ibid: 96).

[40] There is much to say about this archaic word used to describe a visitor with added, almost revelatory significance. It needs us to consider Frost’s 1955 novel The Visitants. But even in this novel the concept of the visitant is connected with disruptive if comic revelation: ‘… Tom Aston was surprised by the trick cyclist, the visitant from the Tour de France and the Assyrian horde’ (my italics). Tom first meets Harry in the imagined guise of a ‘Beethovenesque trick-cyclist, metamorphosised into a terrible Tamburlaine’ We shall see Harry in this role again much later in the novel.

[41] Frost (1953: 98)

[42] Martin Salisbury (2017: 77) The Snail That Climbed the Eiffel Tower and other work by John Minton Norwich, The Mainstone Press.

[43] ibid: 114

[44] For instances of Kokoschka’s appearance as a painter (‘all expression and energy’) see Frost (1953:136f., 178).

[45] ibid: 115

[46] ibid: 98

Thankyou for all your efforts that you have put in this. very interesting info .

LikeLike

very good post, i undoubtedly enjoy this fabulous website, carry on it

LikeLike