‘“You poor man – … . We must seem like the characters in one of those novels about mad people in country houses.” She laughed again, …’.[1] Reflecting on John Banville’s ‘Snow’ London, Faber.

This is a novel like no other by John Banville, in that it’s status vis-à-vis the role and status of the writer and writing has become a tacit theme. It is tacit precisely because only high status writing make grandiose claims about its universality and generalisability. The classic statement of that position of the universality of great literature in Irish writing is James Joyce’s The Dead. And it is worth looking at how this achieved by Joyce by looking at a passage that is semi-ironically referenced in Banville’s Snow.

Joyce takes a phrase (the one referenced by Banville), ostensibly from newspaper story on the weather in Ireland, to spin a means of generalising the importance of loss, mortality and the pain of resistance to this general end of all lives in the definition of love out of the idea and image of falling snow.

Yes, the newspapers were right: snow was general all over Ireland. It was falling softly upon the Bog of Allen and, further westwards, softly falling into the dark mutinous Shannon waves. It was falling too upon every part of the lonely churchyard where Michael Furey lay buried. It lay thickly drifted on the crooked crosses and headstones, on the spears of the little gate, on the barren thorns. His soul swooned slowly as he heard the snow falling faintly through the universe and faintly falling, like the descent of their last end, upon all the living and the dead. (my italics)

Quotation taken from: https://medium.com/drmstream/snow-was-general-all-over-ireland-the-last-paragraph-of-joyces-the-dead-48b08b4c3b1f

This passage attempts to use snow and the surface cover it provides to connect and generalise Irish history and geography. It operates almost like a magical incantation by repetitions of words that tend to musical rather than cognitive sense – the repetitions of the word ‘falling’ and ‘softly’ tending to smother the hostility in terms like ‘dark mutinous’, ‘crooked’, ‘spears’ and barren’ and the sense of Armageddon in the phrase, ‘their last end’. It is as if the violence of Irish history and mythology (perfectly symbolised in the contents preserved in the peats of the Bog of Allen) and the stretch of its geography (maybe also symbolised in the Shannon waves) could be covered up and softened by the general visual effect of snow falling universally across it. Whether this is as fanciful as other readings of the last paragraph of the story, there is no doubt that the passage invites such generalisation in symbolic, or, for some people, epiphanic modes.

Above I have tried to show how and why we can dub this famous instance of literary writing one of the most important instances of such generalised or universal forms of literary language. I have quoted it at length because of the extended way it draws out significance from the image repertoire associated with snow as a phenomenon. However its canonical status as a literary phrase makes its appearance in Banville’s Snow the more telling, especially in a novel where snow is used extensively to mark settings in rural Ireland as in its source.

In this detective-cum-country-house story set in rural Ireland, one character, Sergeant Ambrose Jenkins, the almost comical sidekick of the Detective Inspector Strafford, disappears into the snow and is lost. Later he will be found dead, as the second victim of the novel’s plot. The novel isn’t kind to Jenkins, who is noted mainly for the ‘flatness of his head … as if the top of it had been sliced clean off, like the big end of a boiled egg’, in which one might wonder if there was ‘room for a brain of any size at all in such a shallow space’.[2] Quizzed about this disappearance on the telephone by his Chief, Inspector Hackett, a character from the novels by Banville’s alter-ego, Benjamin Black, the following exchange occurs (Hackett speaking first):

“…. Is it now snowing down there, like it is here.”

“Yes, Chief. Snow is general all over Ireland.”

“Is it?”

“It’s a quotation – never mind”. (my italics)[3]

That Chief Hackett does not recognise the reference to The Dead made by Detective Inspector (DI) St.John Strafford. The latter’s upper class family names are an important contrast too to Hackett – it’s pronounced Sinjun says St. John once too often. The contrast tells us much about the difference in the two literary detectives, and perhaps of the differing expectations that readers might be said to have of novels by Black and Banville, respectively.

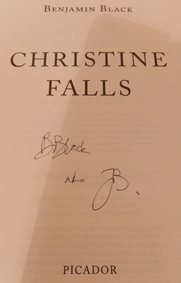

Banville’s early reputation as a significant writer of Irish English, and thus the heir, as was often said of Beckett and Joyce, is almost posed in this difference, between him and Black. The original need of Banville to create ‘Benjamin Black’ can be interpreted (rightly or wrongly) as a means of facilitating writing new fiction of definitively lower literary expectation than his written oeuvre up 2006 when Black made his debut with Christine Falls: A Novel. When I asked Banville at a literary festival to sign that novel ‘John Banville’ in the year of publication, he demurred but eventually added an ‘aka JB’ to the Black signature (see below).

There is no doubt however that Banville and Black novels have sought to complicate the distinctions that could be made between themselves of late. The name Benjamin Black, of course, must owe something to the name of Banville’s first-person narrator, Benjamin White, in Nightspawn (1971). In Prague Nights (2017), which is ostensibly by Benjamin Black, the author revisits the characters of Banville’s famous early astronomy-philosophical novel Kepler (1981). The last is one of his finest literary philosophical novels of which the Guardian review by W.L. Webb said it was, ‘Narrative art … at a positively symphonic level’. (Cited on dust-jacket of Banville (1986) Mefisto).

Snow contains as distant characters Quirke, the forensic pathologist to whom reference is made, and Hackett, Strafford’s superior, whose role continues in the background governance of Strafford’s work. But like Banville’s work in total, Snow is an allusive novel, as the key example of the use of The Dead as a literary counterpoint shows. The allusive content is more playful and less dense than in a novel, like, for instance, Shroud (2002), but it is there, although as likely to allude to Lewis Carroll than Greek Tragedy.

I am convinced that the playful quotation I use in my title refers to Banville’s early novel, Birchwood (1973). The historic owners of the eponymous country-house in that novel are the Lawless family, ancestors of the wife of the current tenant. Lawless is also, of course, the name of the first murder victim in Snow. Banville has referred to this novel as his ‘Irish novel’ but its genre is that of the Irish country house Gothic novel with a forebear in Edgeworth’s Castle Rackrent. Interviewed by Stuart Jeffries for The Guardian in 2012 Banville himself referred to it as a failed attempt to write an ‘Irish novel’:

“It was my Irish novel and I didn’t know what to do next. I thought of giving up. I hated my Irish charm. Irish charm, as we all know, is entirely fake”.[4]

The architecture of the country home in Snow is likewise fake: ‘Arts and Crafts fakery’, thinks DI Strafford ‘straight off, with a mental sniff’. Thus, it too, like Birchwood has allegoric connection to the state of Ireland in the 1950s. The sexually neurotic lady of this house Sylvia Osborne, not a Lawless but a suspect in a murder of a Lawless, makes an ironically allusive remark about her home and family that so precisely, if in brief, describes the kind of novel that is Birchwood:

“You poor man – what must you think of us all! We must seem like the characters in one of those novels about mad people in country houses.” She laughed again, less shrilly this time. “Lettie says I’m mad, you know.[5]

The allusion to novels from one’s own past is typical of the kind of patterns between novels made by settings, narratives and characters throughout Banville’s work and is now knitting together the Black and Banville novels. It has a lot to do with the way these novels wade through heavy themes from the past of a nation, especially the religio-personal politics of Ireland like a strange medium. Existential moments become submerged into a world of unusual visions and psychosis, which makes the Gothic a perfect medium to which those novels allude most strongly. This novel in particular has the connections between power, authority, sex and the damage that confluence of drivers reeks on personal lives.

Hence the primary murder in Snow is of an abusive paedophile Catholic priest, overfond of the Anglo-Protestant country-house traditions of a still privileged monied elite. His penis and gonads are removed during his killing and stored in a jar by one of the murder suspects. This boy was once his sexual victim and is now a damaged feral young man. The ability of the Catholic hierarchies to smooth over and cover up, as if under snow, their communal sins of political and sexual hubris keeps being asserted.

The Catholic Archbishop who tries to threaten Strafford to mute his discoveries or attempts to uncover is described as if at one with how winter covers up and deadens truths: he has a ‘wintry smile’ and says of the snowy weather through which Strafford beats a way to find him, that it is, ‘another of the trials it pleases God to impose on our souls’.[6] Standing ‘in front of the fire’ later however, he has a tinge of the infernal Mephistopheles of an earlier Banville novel Mefisto (1986) as he leans ‘his head towards the flames, which gave a lurid tinge to his thin, pallid face’.[7] The Gothic is a place of monsters that combine images of life and death together together with sex and power, disgust and pleasure.

The semi-sexual relationship between Lettie, Sylvia’s daughter, and her feral friend, Alphonsus (Fonsey), who keeps her father’s (and his past abuser’s) hunting horses, is located in the cusp of power and pleasure, flesh and mortality. Fonsey lives in the midst of rotting flesh: ‘To the other smells he added his own raw tang, a blend of leather, hay, horse-dust and swarming hormones’.[8] The strange sexual entanglement between him and Lettie is full of disgust with the externals of sex, such as in Lettie’s contemplation of Fonsey’s act of oral sex on her, whilst noticing a lurid sore place on his mouth. There are also her perception of his ‘ugly’ acts of masturbation and even the ‘strange flavour (‘like salt and sawdust soaked in milk’) of the ‘globs of goo’ that Fonsey emits that she will not, except once for the ‘tiniest taste’, allow inside her body.[9]

I don’t quote this for the pure shock value that inevitably accompanies it but because it associates socially sexual life and human interaction with disgust. This feels to me to part of the dark Banville vision. The association of snow and sexually viscous liquids become the world of Banville’s characters in Snow. One of the associations of melting snow, with its pretence to innocence and its ambivalent cultural association between good and evil that go with the repression in terms of being both covered up and slimed with the idea of something unpleasant. Take for instance, Strafford’s car trip as he leaves the home of the sister of the murdered cleric and the knowledge of their mother’s incarceration in the ‘madhouse, up in Enniscorthy’. Here internal sensation of the movement of bodily fluid spills out into the perceptible ‘feel’ of the external environment and becomes visceral.[10]

His pulse was racing, and his palms were moist on the steering wheel. There was a nightmare he had, it recurred with awful frequency, of being trapped in the dark in what seemed to be a sort of fish tank, filled not with water but some heavy, viscous liquid. To escape from the tank he had to clamber up the side, his fingers and toes squeaking on the glass, and heave himself over the rim and squirm off into the darkness over a smooth, slimed floor.

The snow was falling heavily, coming down in big flabby flakes the size of Communion wafers and lodging in icy clumps around the edges of the windscreen and making the wipers groan against the glass. …

…. Since his arrival …, time had become a different medium, moving not in a seamless flow, but jerkily, now speeding up, now slowing to an underwater pace. It was as if he had strayed on to another plane, on to another planet, where the familiar, earthbound rules had all been suspended.

He thought of telephoning Hackett and asking to be taken off the case, this case in which he was floundering, and in the slime of which he might drown.

… Everything was upended (in this crime), everything swayed and wallowed. He was in the tank again, up to his neck, and each time he managed to get himself out and flop onto the floor he was scooped up by invisible hands and tossed back in.

(my omissions and explanatory addition – to account for one omission – in italics)[11]

This takes up something from Lettie’s consciousness of the world of flesh and bodily fluid, of ‘tiny little tadpoles squirming out of it (sperm of course) and racing each other up along your tubes’ (my italicised explanatory addition).[12] It is embedded in a childlike disgust of sex and the fear of inside feeling and thoughts that squeeze out into our external life, and are associated with a viscous visceral enveloping of the self in a medium one wants to escape. The jerky movement of time is like Fonsey’s earlier masturbation and the memory of his sexual appropriation by priests. That this is both snow, and the feel of its wetness is aided by the way exuded sweat feels on a steering wheel once an excited pulse of internal blood heats the body uncomfortably. This together with the ‘groans’ (of fear or of excitement) of alien machinery like the windscreen wipers.

I quote at length because without it we fail to see how metaphors arise, get transformed and then re-emerge as in the structure of a dream. What I want to emphasise is that this passage is pure Banville not Black, although Black’s crime novels deal with the national political and sexual crimes of the Catholic church in relation to children. So please read Snow if you want to see how a superb control of sentences in writing – of pace, rhythm, and timing of visceral sensation in prose – can work at its best. He is a masterly writer. To test the cognitive, visceral and emotional semiotics of that consider the simile in the passage describing snowflakes in this viscous writing: ‘flabby flakes the size of Communion wafers’. Here the transubstantiated body of Christ is shed in too fleshly a way and too universally.

Steve

[1] ibid: 219

[2] ibid: 13

[3] Banville (2020: 213)

[4] Banville (2012) cited in Jeffries, S. ‘Interview: John Banville: a life in writing: ‘I’ve never understood women. Never will, don’t want to. I’m in love with all of them’ Available in: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2012/jun/29/john-banvill-life-in-writing

[5] ibid: 219

[6] ibid: 201

[7] ibid: 207

[8] ibid: 71

[9] ibid: 104f.

[10] ibid: 175

[11] ibid: 177f.

[12] ibid: 105

Regards for this post, I am a big big fan of this internet site would like to keep updated.

LikeLike