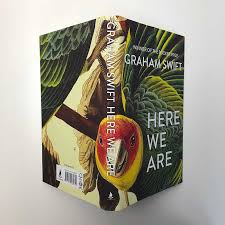

Writing novels as a kind of magic in Graham Swift’s Here We Are (2020) London, Simon & Schuster UK Ltd

Graham Swift’s novels often deal with a moment in the remembered past that has to be relived by witnesses, such as the characters who might have been present in that past or those asked to imagine or re-imagine it in a story told by some significant other. And these moments are also are what make novels live, if they live, in the imagined outcomes configured by a novelist’s writing. It is as if the role of the novel was to conjure up this past moment, to make it feel real and beyond the stuff of fiction, a kind of embodied past that appears before our sight and which we might touch.

Artists have long looked longingly at the image of the magician, able to make things that might have been as insubstantial as a dream or tale into what can be realised or sensed as if realised. It is this ‘as if’ quality that we yearn towards – something emergent appearing from words and narrative and yet as capable of disappearing. Magicians deceive and use ‘tricks’ but they only do so when those tricks might seem to be transcended by what is conjured from them and what appears other than them. Prospero is one such in The Tempest but true and false magic also plays a part in the very earliest literature – in the Homeric epics and in their followers down to to Spenser’s evil Archimago in The Faerie Queene, conjuring false delusions from fragments that look like transcendent truths – for every true Una, there is a false Una, actually a Duessa.

Swift’s latest novel takes that tradition and crosses it with John Osborne’s The Entertainer. It calls up from the past the variety theatre magician before, during and after the Second World War at the cusp too of the disappearance of this box of curious art forms. Its moment of telling surprise focus on a lost and gain of an exotic parrot, who asserted his presence, ‘Here I am’.

Swift’s prose is never ‘showy’ but it evokes the past in the magic of its control of appearance and disappearance that links the interactions between words, pictures and the imprints of other senses in the storage of memorial records. I looked back at this passage where the recall of pier-end music hall is initiated:

… The show must go on.

‘You’re in Brighton, folks, so bloody well brighten up,’

It went on through to early September, and the public only saw the marvel of the thing, the talked-about thing. Then the show was over and the talked-about thing was no more than that, it could only exist in the memories of those who’d seen it, with their own eyes, in those few summer weeks. Then the memories themselves would fade. They might wonder anyway if they really had seen it.

Other things were over too. Ronnie and Evie, having had a remarkable debut, coming from nowhere to achieve summer fame and having secured for themselves, it would seem, future-bookings, even a whole career, never appeared on stage again. Ronnie never appeared again at all.

Swift (2020:4f.)

One reads over this at a fairly fast pace despite its evocation of the importance of the passing ‘show’ and its fascination with both the laying down of visual memories and the inevitability, in the long duration of time, of their disappearance.

The artist, at base, produces a ‘talked-about thing’ but when the talk stops does the art itself fade, or perhaps even disappear in a puff? That magical disappearing act can be illusory; a mask and myth to cover over the more painful experience of the loss of its meaning in the fading of its popular colours. That this is almost an allegory of artistic production and the maintenance of the art object as a ‘talked-about thing’ in a reader’s culture, or otherwise.

This is true of all art perhaps and I think Swift is operating here much as Tennyson does in In Memoriam, showing that writing in order to recover that which is lost from sight and sense (in Tennyson’s case Arthur Henry Hallam, also becomes a potentially fading memorial matter itself. That is so even if the material holding memory are the material (chemical, eletrical, neuronal) patterns in the human brain. Everything is still at risk of loss as public ‘passion’ and fashion for what constitutes the ‘talked-about thing’ changes.[1]

Art is, of course, often about art. This point itself can’t be mentioned, as art itself, any one of its manifestations, is vulnerable to passing into a past discourse; together with the transience of the media that attempts to recover its loss. This is poignant especially in the passing of artistic reputations in modernity. It can seem incomprehensible but is, in whatever focus of duration in time, inevitable.

So find here, in the passage cited above, a finger pointing to issues of ‘appearance’ and ‘disappearance’ in which slower but definite and conclusive processes in time, merge into assumptions and wishes for more distinct magical explanations. Ideas of appearance and disappearance in a novel obsessed by not only time but magic, ‘wizardry’ and ‘tricks’ of which one might, or might not, as an audience, be in the secret. Pablo the Great’s colour, whether Pablo be a flesh and feather parrot or the nom-de-plume of an artist-magician, may not fade with age or fashion-change if its disappearance is instantaneous and a thing to be ‘talked-about’ as a ‘finale’ where Ronnie:

…took the parrot and launched it out towards the audience like some bouquet that was theirs to catch. But it was gone. Gone.

As was Ronnie.

ibid:187

Artists do give both their artistic products, and perhaps their artistic selves, as a thing for audience to catch onto or not. Sometimes it is better to make them uncatchable, gone before they reach the grubby hands to which they fly.

So here is a novel where none of those refracted colours may be caught. Even so, it remains a story of the losses and accidental gains that emerge as a loved artist’s career progresses. These colours that might disintegrate in the very shortest space of time were it not for a novelist’s license to use tricks. Or are they tricks? Aren’t they also magic, even in the eyes of cognoscenti like the wonderful parent substitutes of the novel, the Lawrence’s.

The Lawrence’s fill that gap where family breaks up and disintegrates in the pressures of extraordinary time – the experience, that is, of the refugee children (refugees between internal parts of the UK) who might have escaped economic constraint at the cost of emotional losses – and emerges as an ‘act’ played out in real time. Emotions don’t disappear, like those for the near-absent ‘real’ father, Sam the Sailorman (‘those were the pearls that were his eyes’) drowned in the War. Replaced by Prospero losing a Dad may not be seen externally as a loss, but loss it is deep and within.

Like all of Swift’s later fiction this novella will in probability, except for some magical change in the shaping of readerly perception by the publishing enterprises, not be seen as the marvel it remains. But it is glorious. An artist will stand again and say, ‘Here I Am’.

It seemed that Ronnie had become a magician more by chance than intention, though once the seed was sown, the wish had taken hold of him completely. Perhaps the sowing of the seed was itself a stroke of magic.

ibid:106

The sowing of both biological and magical/imaginative seed by two fathers in this novel – Sam and Eric, the effect of being born biologically and magically from two mothers (constrained and unconstrained) and nurtured by all four ‘parents’ is implied here as I read the novel. Do read it!

And I mean READ it. Only then will the magic appear from behind it’s disguises.

Steve

[1] See Lyric LXXVII

What hope is here for modern rhyme

To him, who turns a musing eye

On songs, and deeds, and lives, that lie

Foreshorten’d in the tract of time?

… (see lyric in full: https://kalliope.org/en/text/tennyson20020216077)