Reflecting on free ethical action in Aravind Adiga’s Amnesty (2020) London, Picador

Amnesty (from the Greek ἀμνηστία amnestia, “forgetfulness, passing over”) is defined as: “A pardon extended by the government to a group or class of people, usually for a political offense; the act of a sovereign power officially forgiving certain classes of people who are subject to trial but have not yet been convicted.” An amnesty constitutes more than a pardon, in so much as it obliterates all legal remembrance of the offense. Amnesty is increasingly used to express the idea of “freedom” and to refer to when prisoners can go free.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amnesty

Australia’s experience of amnesties in the immigration field date back to Australia Day (26 January) 1976 when Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser granted amnesty to illegal immigrants. At that time, this meant individuals who had entered Australia lawfully but overstayed their visas.

https://openborders.info/blog/tag/malcolm-fraser/

Danny had something to add to the feast: hope. There is a way out of our sham, … and the illegals gathered around him. … See. Danny had been reading in the library. Back in the 1970s, a man named Malcolm Fraser was prime minister, and one day he announced …. “Illegals of Australia, tomorrow is your amnesty.” …

Amnesty. Gates will swing open, manholes will fly, and an underground city will walk into the light.

Bullshit, said Ibrahim the Pakistani. …

Adiga (2020:135 – italics in original)

This is a novel built on a notion of illegality that is used to brand large groups of people, enough to make up an ‘underground city’, as non-citizens such that they are seen and see themselves as ‘illegals’. But to be branded illegal raises another issue, which is the source of anyone’s duty (whether that person’s citizenship be recognised or not, whether they are ‘legal’ or ‘illegal’) to act to protect others against injustice.

This question is an important one. In essence, it asks if a person’s action is ever more than based in selfish instincts of self-preservation – the assumption we all remember of Dawkin’s concept of the ‘selfish gene’. That theory, a corruption of Darwinism, argues that ethical and altruistic behaviour is merely extended to those who share more of our genes, and was once therefore used as a ‘scientific’ rationale of racism and nationalism, to support the ethical nature of immigration policy and, of course, to justify behaviour that protected self before all other possible calls on our action.

In Amnesty, this is tested in Danny’s painful and long-revolved decision about whether he ‘dob in’ a man whom he suspects to have murdered someone else, a woman, who had employed and befriended Danny over a long period. The putative murderer, the murdered woman’s lover and also known to Danny, has a case against him built progressively for the reader in Danny’s consciousness through the novel in flashback memories and circumstantial evidence. The problem is that, were he to dob in Prakash, the male lover, he must also be simultaneously naming himself as an illegal for deportation. It is ultimately then a novel focused entirely on that decision and why it matters in terms of Danny’s history as a Sri Lankan Tamil, deportee from Dubai and breaker of the conditions of his entry to Australia as a student.

This decision is so crucial to the imagination of his continued existence, Danny sees Prakash as if he were an evil doppelganger in a contest for identity only one of them can win:

Prakash had that terrible look of a hungover fortysomething-year-old, now at the stage of his life when the drinking depletes some permanent reserve of strength inside. … Danny watched him.

No. This is just an animal inside him. An instinct is sitting here, not a man, and Danny had this same instinct inside him. … This is all Prakash is today, an instinct to survive, a black rock in the center (sic.) of a dried-out pond with letters inscribed on it: I AM YOUR SELF-LOATHING.

ibid:141

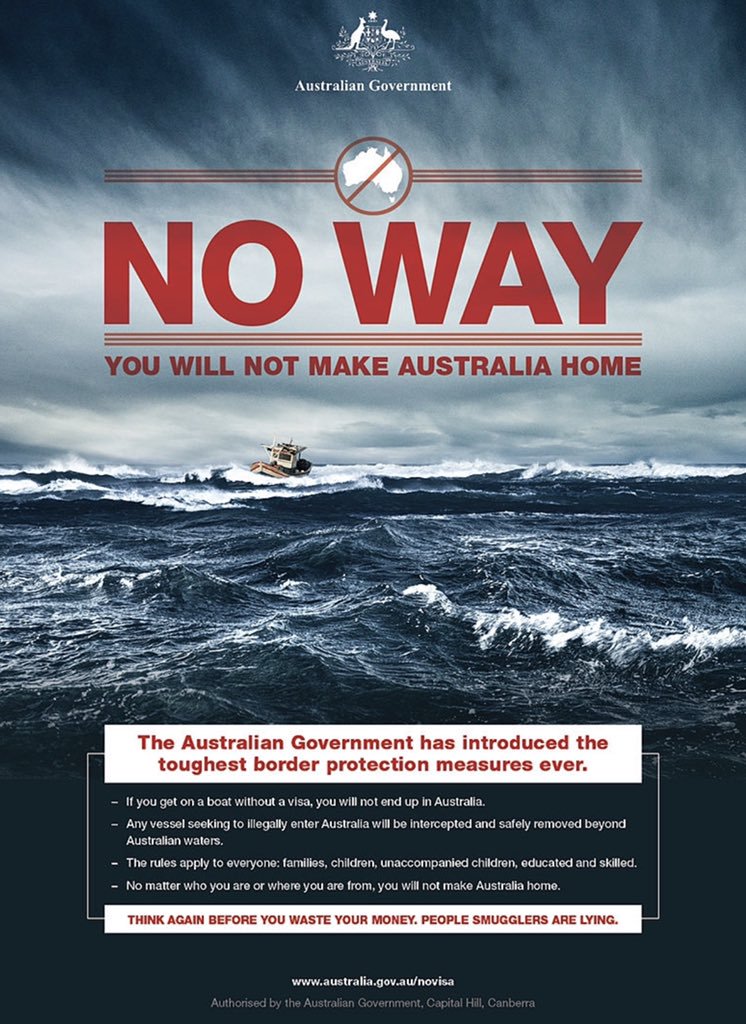

The reason the novel has any duration whilst focusing on this moral problem alone is that, whilst it validates the desire to be a whole person more than any selfish instinct (imagined-to-be-genetic or otherwise) it does not belittle how unequally societies of all kinds stack the ethical odds against the marginalised. To hope to survive as self, or as a group, also has its noble side. Hence the centrality of the problem of the illegal and Immigration Laws that stand behind that right to so name whole groups of people. Hence, in a country now that is ready to adopt wholesale the Immigration Policy in action within this novel, this novel has a great urgency in asking why we want to create so many more ‘illegals’ within our paltry borders.

And becoming an illegal, the novel shows, works much the same as becoming the object of racist hate. I love the section where Danny first sees that there was once something to admire in Prakash, which is his effective non-violent resistance to racism, even in small acts in a bar. The TV showing the capture of an illegal to over-excited whites, is unapologetically turned off by Prakash:

Stunned, the three white men, …, just gaped.

…

In a green field outside Batticaloa, Danny had once seen a bull elephant rolling up grass into a ball and devouring it between his tusks; Danny had not been able to take his eyes off it – that solitary defiant animal – and, under his breath, had given it a magic nickname: Prabhakaran. Or the nonapologist. (sic.)

ibid:108

Sometimes it seems animals have the right instinct – to assert their own being without apology. The novel indeed can be very clever, in a novelist’s way, with the nuance that hangs around the reasons we give or don’t give apologies (see ibid:117, 160). Sometimes running out of danger and indeed of responsibility, is itself a responsibility, as Danny learns watching the fate of a Muslim boy helping the Muslim rebels:

This business of helping others will make bigger monsters of us than greed ever did.

Rights? You have the right to run, Danny.

You have the fucking responsibility to run.

And that’s all.

ibid:160

And the complicating factor in the decision to dob in Prakash, as evil as the act of murdering his lover is, is that Danny recognises his degradation in a white society that predicates that the use of power rests on two things: first, an assumed racial ‘superiority’ and, second, the need to demonstrate that power again and again on ‘brown’ people. I quote the following because of the, to me, wonderful way Adiga shows this. Blink whilst reading the novel and you might miss it!

There is a buzz, a reflexive retinal buzz, whenever a man or woman born in India, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, or Bangladesh sees another from his or her part of the world in Sydney – a tribal pinprick, an instinct always reciprocal, like the instantaneous recognition of homosexuals in a repressive society.

ibid:140

In a novel where instinct, and what an instinct is, is so important we should be alerted by this. The notion of tribalism supports the idea of genetic instinct, or at least recalls that paradigm. However, Adiga suddenly calls on an omniscient narrator to explain mutual ‘racial’ recognition as a multi-sensory (sound, vision, feel – pinprick) learned response akin to what ‘homosexuals’ learn but only as a result of a ‘repressive society’.

For me, this was a magic moment that queered the novel in an important sense in that it let go of the debate between biological instinct and the rule of social law and showed the boundaries of the protagonists to be very fuzzy and perhaps a convention at most.

It may be that this novel may legitimise cultural notions of the ‘honest heart’ in opposition to the paradigms that say that we always act, even when we act in ways that we call ethical, selfishly. There is no doubt that power in society often conflates ethics with self-interest, as in the case of Danny’s landlord where money is the real goal of most actions. But you get the same buzz in the next paragraph as you get sometimes as in acts of moral good in E.M. Forster’s novels, based on a fleeting suggestion of an aestheticised morality.

It might have become a ghost (a thing not a person) this spirit of free, and undetermined, ethical action but we know from how we feel when we look at it, that it is GOOD! Revolving the ways he has been threatened with being dobbed in as an illegal in the past and the horrors that involves (more so in current-day Australia) we get this:

Turning to his right, Danny saw a great fig tree sparkle in many places inside its dark canopy of leaves, like a thing that knew its own heart.

ibid:192

Knowing its own heart is perhaps the reflexive moment in which free, if tragic, decisions are made. And if the self is darkly motivated, it can still ‘sparkle in many places.’

Another great novel from a great novelist, who is interrogating the individual heart in its politicised contexts.

Steve